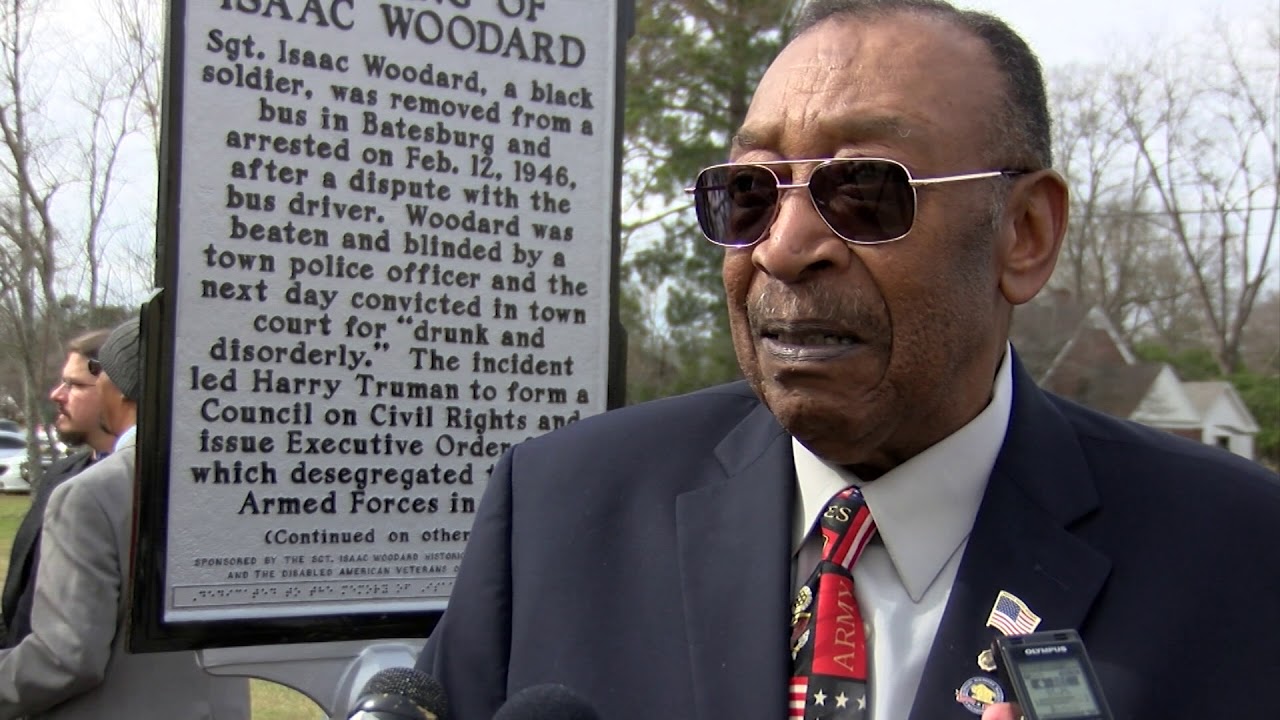

By Alan Davidge

Poland does not always get the recognition it deserves for helping to defeat Nazi Germany and end the war in Europe. Yet it was servicemen from Poland who tipped the balance in some of the most crucial encounters of the war.

During the Battle of Britain in 1940, Polish fighter pilots, flying alongside the young lions of the RAF, displayed remarkable aggression, bravery, and skill, and helped force Hitler to shelve his plans for adding the invasion of Britain to his list of lightning conquests.

At Monte Cassino in May 1944, when Monastery Hill lay piled high with the bodies of American, British, New Zealand, and Indian troops after four months of bloody fighting, it was the Poles who finally made it to the top, opening up the route to Rome.

Similarly, in Normandy, after 10 weeks of battle when the remains of the German army were frantically trying to escape through the Falaise Pocket, it was the Poles who stood and blocked their way at a geographical feature known as Mont Ormel. And leading the Poles was 52-year-old Maj. Gen. Stanislaw Maczek, commander of the Polish 1st Armoured Division.

In 1937, as a colonel, he had been given the task of organizing Poland’s first fully mechanized unit, the 10th Mechanized Cavalry. In September 1939, he was commanding this unit near Krakow in southern Poland when the Germans invaded, and he led his brigade in screening the retreat of Army Krakow, distinguishing itself in numerous actions.

Following the collapse of the “Rumanian Bridgehead” in the wake of the Soviets’ invasion that began on September 17, 1939, Maczek and the remnants of his command retreated into Hungary, where they were interned.

After escaping from Hungary, Maczek made his way to France, where he was charged with rebuilding a Polish mechanized force and was promoted to the rank of brigadier general. In May 1940, this new unit—the 10th Armoured Cavalry, made up of many veterans of the Polish 10th Mechanized Cavalry who had followed their commander to France—saw action again during Germany’s invasion of France.

According to one historian, Maczek’s unit “again found itself screening a retreat, this time of the French Fourth Army. Maczek’s men distinguished themselves at the battle of Montbard on June 16, 1940, but once again the fortunes of war left Maczek and his command fugitives and refugees. Although some Polish soldiers were prevented from escaping by unsympathetic French authorities, General Maczek and many of his men managed to escape to England.”

Maczek and the other Polish survivors offered their services to the Allies and were sent to Scotland in February 1942 to form a new unit—the 1st Polish Armoured Division, which was equipped with British uniforms and vehicles. For over two years, Maczek trained and molded a diverse group of recruits into an effective fighting force. A month after the D-Day invasion of France, Maczek’s men were ready for combat, and after the breakout from the Normandy beachhead, the division was shipped to France in July 1944, where it became a part of the Canadian I Corps.

As the Poles were finding their feet in Normandy, their allies were watching Operation Cobra unfold. Troops had broken out of the beachhead at the end of July, and Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., who had been waiting like a coiled spring to make his mark on the battlefield, had pushed his U.S. Third Army as far as Le Mans, arriving there on August 8.

Conversations were taking place between Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, commanding 12th Army Group, and General (soon to become Field Marshal) Bernard Montgomery, commanding 21st Army Group, about the next stage. It was decided that Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip’s XV Corps from Third Army would swing north in the direction of Argentan, with a view towards encircling the German Army. For extra support, Patton would utilize French General Jacques-Philippe Leclerc’s 2nd Armoured Division, which had landed at Utah Beach just a week earlier after years of fighting in exile.

At the same time, Hitler was demanding a major counterattack westwards in the direction of Avranches at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula. This, Hitler believed, would drive the advancing American divisions into the sea and cut off other units of the Third Army that had begun to liberate Brittany. Operation Lüttich, as this counterattack was known, was launched on August 4 and proved to be his undoing.

American troops were initially caught wrong-footed by the German counterattack, and the town of Mortain, which had just been captured by the 30th Infantry Division, was quickly reoccupied by the Germans. A heroic action by an American battalion stationed on Hill 314 above Mortain checked the German advance, and they held out for six days until relieved on August 12. By concentrating their efforts on trying to capture this strategic piece of high ground, the German army lost valuable time and considerable resources.

It was becoming clear to both Montgomery and Bradley, after their initial discussions on August 8, that there was a real opportunity now to capitalize on this German weakness. Every day that the Germans spent trying to advance west, spreading themselves ever more thinly in the process, gave the Allies time to move eastwards, north, and south of the counterattack like pincers until they reached the point where they could join up behind them and surround the whole German army.

Bradley famously announced at the time, “This is an opportunity that comes to a commander not more than once in a century. We’re about to destroy an entire hostile army and go all the way from here to the German border.”

Despite Bradley’s apparent adrenaline rush about the possibilities of encirclement, he did not feel confident that Haislip’s XV Corps had the strength to advance beyond the town of Argentan, and he ordered Patton not to take the final step and join up with the Canadians when they arrived at Falaise.

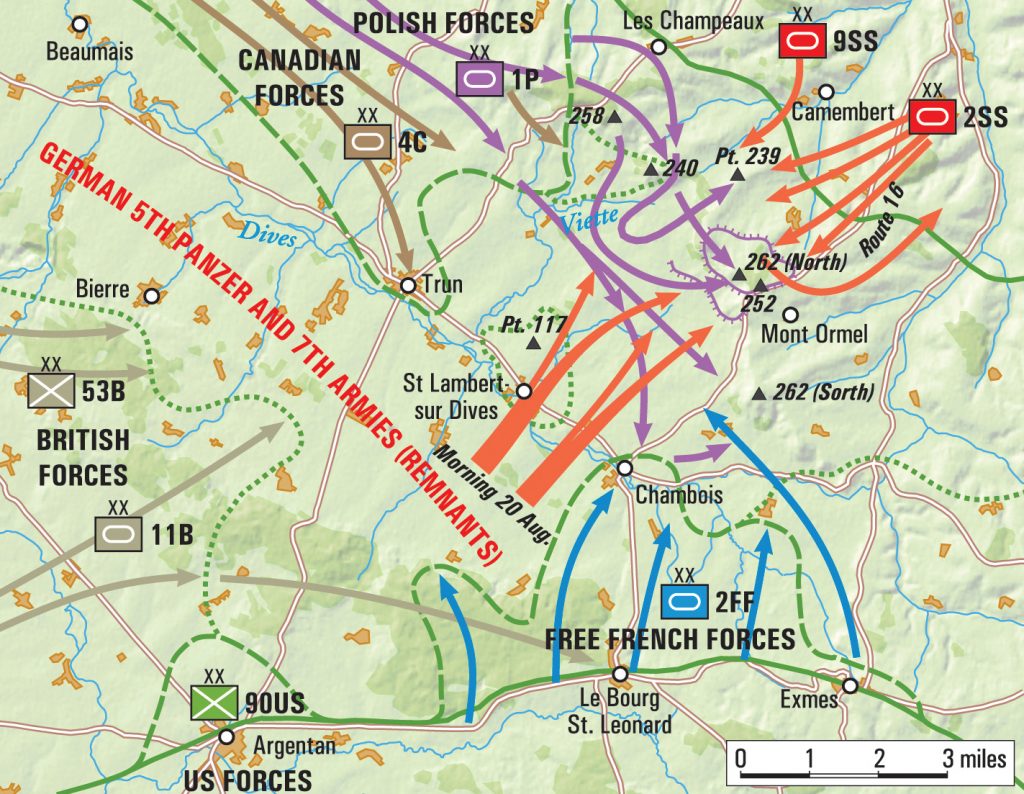

There were heated exchanges between Bradley, Patton, and Montgomery, and their lack of agreement on a way forward has been fastened upon by historians ever since as a missed opportunity to complete the encirclement. The eventual result of this delay and indecision was that the action to close the pocket took place between the small towns of Trun and Chambois, to the east of Falaise and Argentan—where it had originally been intended to happen. It also allowed 116th Panzer Division to strengthen a position in the southern part of the pocket that enabled more of their comrades to escape.

While Bradley was contemplating maneuvers on the southern side of the German retreat, 21st Army Group was focusing on the other half of the encirclement plan from the north. Initially II Canadian Corps under Lt. Gen. Guy Granville Simonds mounted a series of attacks from the direction of Caen toward Falaise from August 7-11, starting with Operation Totalise. Two key units in this plan were the armored divisions: the 4th Canadian under George Kitching and Maczek’s 1st Polish.

During his time in Britain, Maczek had built up a formidable fighting force containing many of his former officers. His division’s 10th Armoured Brigade was led by Colonel Tadeusz Majewski and included the 1st and 2nd Armoured Regiments under Lt. Col. Aleksander Stefanowicz and Lt. Col. Stanislaw Koszutski, the 24th (Lancer) Armoured Regiment led by Lt. Col. Jan Kanski, and the 10th Dragoon Regiment (Motor) under Lt. Col. Wladyslaw Zgrzelski.

The 3rd Infantry Brigade came under the control of Colonel Marian Wieronski and comprised Lt. Col. Karol Complak’s Polish Highland Battalion and the 8th and 9th Infantry Battalions under Lt. Cols. Aleksander Nowaczynski and Zdzislaw Szydlowski.

These were supported by further divisional units that included an anti-tank regiment, two field-artillery regiments, and the celebrated 10th Mounted Rifle Regiment, or PSK, under Major Jan Maciejowski. Shortly after they arrived in Normandy, Maczek signalled their priorities: “The Polish soldier fights for the freedom of other nations but only dies for Poland.”

Operation Totalise unfortunately got off to a bad start on August 8 as some of the bombs intended for the enemy fell short, and Polish troops were among the casualties. The First Canadian Army’s initial advance was successful, however, catching the Germans by surprise. But then a counterattack was launched by Kurt Meyer, the 116th Panzer Division commander.

One of the men he sent forward to engage the Allied tanks driving south to Falaise was Michael Wittman, the legendary tank commander they called “The Black Baron,” who had the destruction of 168 tanks to his credit.

However, a 17-pounder shell from a Canadian Firefly tank belonging to the Sherbrook Fusiliers put an end to Wittman’s Tiger tank from across the Caen-Falaise road near Gaumesnil, killing Wittmann and all the crew.

After four days, Totalise was terminated, despite the 1st Polish Armoured having given a good account of themselves. The Poles especially showed their mettle on the night of August 10 by attempting to outflank German units installed on the high ground of Hill 195 overlooking their route and by breaking through the Waffen-SS lines.

When Totalise was called off, the Poles had advanced eight miles along the road to Falaise. At this point, Simonds reviewed his plans, updating them to take account of the U.S. Third Army’s progress on the south side of the German retreat and Montgomery’s directive to First Canadian Army, which would involve II Canadian Corps taking Falaise. This next phase, Operation Tractable, began on August 14.

On August 15, the second day of Tractable, Simonds ordered the Polish 1st Armoured eastwards, giving it a separate role from the remainder of the corps, a degree of independence that was relished by Maczek. The division divided into two groups, which headed for the small towns of Vendeuvre and Jort to find a means of crossing the River Dives.

By the end of the following day, they had managed to shrug off resistance from two German divisions, and Maczek’s engineers had established a bridgehead at Jort, the more southerly of the two towns. Having crossed into open country, he was able to drive southeastward and catch up with groups of retreating German troops and destroy them.

The next day, two Polish battlegroups were moved south of the Jort bridgehead. The first group reached a location close to Morteaux-Coliboeuf, four miles south on the Dives; the second stopped near Baron-en-Auge, which was a little to the east.

On the 17th came Montgomery’s order for the Canadian and Polish armored divisions to accelerate at all costs southeast in the direction of Trun and thence to Chambois to join up with Patton’s Third Army, thereby enclosing the retreating German Army—now under the command of one of Hitler’s seasoned favorites, Walter Model.

Unfortunately, during the night of the 17th/18th, the Polish 1st Armoured made one of its rare mistakes. Using a guide to get to Chambois in the dark, the tactical group Koszutski accidentally arrived in Champeux, running directly into the 2nd SS Panzers. The Koszutski group was saved by a fierce attack by its own 8th Infantry Rifles, although the group did not completely disentangle itself until midday.

By the morning of the 18th, it became clear that there were still a few small gaps between Trun and Chambois through which the German Army could escape. The 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade had liberated Trun fairly early in the day and, to the south, elements of the 359th U.S. Infantry regiment, 90th Division, held Chambois.

Between these settlements, however, escape routes were being forged north-eastwards, passing on either side of Mont Ormel, a twin-peaked hill rising to 262 meters, the top of which provided an excellent strategic view of the Dives valley and which, in Allied hands, could target anyone trying to escape this way.

Toward the end of the day, a group led by Major David Currie consisting of C Squadron, South Albertas (Canadian 29th Armoured), and elements of infantry from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada tried and failed to capture St. Lambert, located in the middle of the gap between Trun and Chambois.

Next morning, the 19th, their second attempt succeeded. It looked like the village of St. Lambert, with its little bridges across the Dives, was becoming the focus of the German retreat. Soon, A and B Squadrons of the South Albertas were set up close by in positions that could further frustrate any attempts to cross the river.

Fighting remained fierce for the next couple of days, and the best that the Albertas could do was to try and hold on to St. Lambert. It had been hoped that they would be able to join up with the Americans at Chambois, but the tide of German troops was almost impossible to contain, and they could not afford to lose their grip.

August 20 saw the Canadians fighting for their lives in St. Lambert, trying to hold back the 353rd Infantry Division and elements of four panzer divisions. For his actions in keeping St. Lambert in Canadian hands, Major Currie was awarded the Victoria Cross.

While the Canadians had been planning to attack St. Lambert, Maczek was preparing to move his men from the Trun area, still under instruction to head in the direction of Chambois. Once underway, he directed a third of his division to Chambois and led the remainder in the direction of Mont Ormel, the twin-peaked hill to the east, which he nicknamed The Mace (or maczuga in Polish) because of its resemblance in profile to a medieval weapon.

On the map, there were two high points on the north and south of its western flank, both registering 262 meters. As a mountain infantryman in his earlier life, Maczek fully understood the positional advantage of the maczuga. It was an ideal place where he could dig in and follow the German retreat as it unfolded along the low ground beneath.

Unfortunately, his division, which was now only two-thirds of its original size, was cut off from the Allied Trun-Chambois axis, where every bullet and shell had to be used against the huge numbers of Germans moving eastwards. Those who successfully ran the gauntlet, and initially there were plenty of them, would be heading straight towards Mont Ormel.

To defend this feature, Maczek had the 1st and 2nd Polish Armoured Regiments, the 8th and 9th Polish Infantry Battalions, and the Polish Highland Battalion, plus anti-tank and anti-aircraft support. However, they were out on a limb and running short of supplies and ammunition. Their precarious location also now meant that the chances of re-supply were minimal.

The remainder of Maczek’s division under Loszutski were at last able to close the pocket down in Chambois later in the afternoon of August 19, when they met up with the 359th U.S. Infantry from the 90th Division. Their battlegroup consisted of troops from the 24th Armoured Regiment, infantry from the 10th Dragoon Regiment, the 10th Mounted Rifle Regiment, plus an anti-tank group. Every German soldier that they could hold back was one less to cause problems for their comrades on Mont Ormel.

Maczek used his previous experience fighting in the mountains to choose the most effective positions for his troops and tanks to inflict the maximum damage on the enemy if and when it broke through the pocket.

Now that he had been able to take a close look at the maczuga, his plan was to deploy troops along the north-south ridge that overlooked the Dives Valley and also block the key exit roads (now the D16 and D242). The two high spots, Hill 262 North and Hill 262 South, would provide maximum strategic advantage.

Early in the day Maczek headed southward with the 1st Polish Armoured Regiment and two infantry companies of his Highland Battalion, initially bypassing the most northerly of the two hills to get to 262 South, which overlooked a route out of the pocket that ran eastwards.

When he got about halfway between the twin peaks, he encountered a slow-moving convoy including Panther tanks and other armor that had escaped the pocket and was heading towards Vimoutiers. They were a sitting target, and the Shermans of the 1st Armoured Regiment wasted no time in tearing them apart.

Such was the damage, congestion and smoke that the Poles could proceed no further, so they headed back northwards, taking some of the German wounded with them to the Boisjos manor house first-aid station near Hill 262 North. Their lack of a presence on the southerly peak would, however, prove costly as other groups managed to find an escape route out of Chambois.

Throughout the day the Polish position was consolidated on the northern half of Mont Ormel, joined by the second battlegroup comprising the 2nd Polish Armoured Regiment, 8th and 9th Polish Infantry Battalions, and more of the Highland Regiment, plus anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns. With a diverse area to manage, and with a justifiable confidence in his officers, Maczek felt he could apply a decentralized approach, with each unit taking charge of its own area.

Both sides were now poised for an explosive confrontation that would occupy them for most of the next day, August 20. Taking advantage of the darkness, small Allied groups tried during the night to get across the Dives at the bridge in St. Lambert, and others made attempts to reach Polish positions on Hill 262, but they were quickly cut down.

There was also a pre-dawn attack that took place in the north of the maczuga that was repelled by Polish Podhale riflemen using just their bayonets, since ammunition was in short supply, setting the standard for the brutality that was to follow.

The pocket was, in theory, sealed, so any Germans trying to break through would have to apply a momentum that the Poles would be hard-pressed to contain. Those who succeeded in getting through would be heading towards The Mace, a weapon that the Poles would wield confidently as long as their ammunition supplies held out. Maczek had a couple of thousand men beside him to stop tens of thousands of the enemy exiting the pocket below.

At dusk, a supply convoy that would have made a huge a difference to the Poles’ fighting potential was lost in a German ambush.

When news arrived of the Résistance uprising in Paris on the 19th, de Gaulle and Leclerc were immediately concerned that it could be crushed the same way as the resistance in Warsaw, something that Maczek would understand. SHAEF commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower sympathized, and off went most of the French 2nd Armoured, taking the U.S. 4th Infantry Division with it, to liberate the capital, leaving a small group behind to provide support in the southern part of the pocket.

When the fighting started on The Mace the next day, the Poles found they had to watch their backs. They were vulnerable to counterattack from the east, a tactic that would also divert attention from the German troops escaping from the pocket to the west of the hill.

The first major attack came not from St. Lambert or Chambois but from the northeast at around 9 AM, and it involved infantry from the SS Panzer Division “Das Reich.” Combat was at close quarters, but the enemy was pushed back within two hours by the 2nd Armoured Regiment and the 8th Infantry Battalion.

Next came an attack from the north by a group from the Germans’ 3rd Paratroop Division with assault guns, and they met a similar fate. There were also signs of a threat from the east. The Mace was beginning to feel like a miniature version of the Ypres Salient in World War I, where troops could never be sure whence the next incursion was coming. It was actually worse than a salient because, until the Canadians could move up from the Trun-Chambois area, they were effectively surrounded.

When they were not spending time defending their positions on the hill, their elevation provided the Poles some excellent opportunities for strategic attacks.

Between St. Lambert and Chambois is the village of Moissy, where the Dives could be crossed via a ford. This route was used by thousands of Germans as an escape route—especially as it led to a track that could take them to Coudehard, just north of Hill 262 North. They were easy targets for the Polish 10th Mounted Rifles (PSK), however, who had occupied a piece of ground known as Hill 113 that afforded a wide field of fire below. History has christened the Germans’ attempted exit routes Couloir du Mort—“The Corridor of Death.”

In addition to looking after a growing number of their own casualties, the Poles on their maczuga found themselves having to supervise more and more prisoners, which amounted to around 800 by the afternoon. An open area, or polana, was allocated for this purpose, but its openness made it vulnerable, and more casualties resulted.

The counterattacks then started to grow in intensity, and at 2 PM, the 8th Battalion was hit from the northeast by a group of infantry supported by panzers; but the attackers were repelled and more prisoners were taken.

The worst assault began from the east at 3 PM, also involving infantry and panzers, and within a couple of hours, it had developed into a ferocious close-quarter battle for the 2nd Armoured Regiment. The intensity was so great that one first-hand account describes every machine gun in the regiment firing at the same time.

In some instances, the hull machine guns of Polish Shermans and their main turret guns were both firing simultaneously but in opposite directions as the enemy was appearing from all angles. Three panzers penetrated as far as the polana, causing panic among the prisoners and resulting in a face-off with Polish Shermans at point-blank range. The attack was eventually beaten off by 7 PM.

The day’s events represented a remarkable achievement for the Poles, as the troops they were taking on were the remnants of Germany’s strongest divisions such as Das Reich and the deadly paratroops.

However, in their subsequent analysis, the Polish 1st Armoured was quick to acknowledge the importance of the artillery support provided by their brothers-in-arms in the Canadian army. Polish forward-observation officers had been registering enemy positions with the Canadians and calling down fire missions throughout the day, which had resulted in the expenditure of around 7,000 shells. This had undoubtedly helped them to hold on to their positions. It also enabled them to continue the operation when their own ammunition stores were approaching exhaustion.

In the early evening, a 20-minute truce was agreed upon to allow the Germans to evacuate a large number of Red Cross vehicles, but immediately afterwards the fighting resumed at the same level of ferocity.

The night of August 20 was a quiet one, the result of exhaustion on both sides. There was, inevitably, among the Poles a feeling that they had been stretched to their limits and beyond. The hoped-for supplies and support from the Canadian Armoured had not arrived, and indeed the slowness of their commander, Kitching, in responding resulted in Simonds relieving him of his command.

The absence of more infantry support in critical spots also meant that some groups of Germans were still getting through, and only the Poles stood in their way. Lt. Col. Aleksander Stefanowicz, a wounded battle-group commander on The Mace, called his officers together in the evening and told them “Gentlemen, everything is lost. I do not believe the Canadians will come to help us. We have only 110 men left, with 50 rounds per gun and five rounds per tank. Fight to the end! To surrender to the SS is senseless—you know it well. Gentlemen, good luck! Tonight we will die for Poland and civilization. We will fight to the last platoon, to the last tank, to the last man!”

At 7 AM on the 21st it all began again with an attack by German infantry and tanks on a vulnerable area in the north, close to Boisjos, where the local manor house served as an aid station. A number of casualties were sustained among those in no position to fight back, including the padre, who was killed in the attack.

The panzers were eliminated but the shelling continued. During the morning a number of C-47 Dakotas attempted to drop ammunition supplies for Polish troops, but most missed their mark and the crates fell among the Canadians.

Then, at 11 AM, soldiers of 12th SS Panzer division made an assault up the steep slope near the church at Coudehard, only to be cut down by the guns of the anti-aircraft unit. Finally, an hour later, the Canadian 4th Armoured Brigade appeared just below Boisjos in the north and found German troops barring the way.

Polish riflemen took charge of the situation once again by charging with fixed bayonets, allowing the Canadian tanks to finally break through and relieve the Polish 1st Armoured Division after their three days of hell.

The statistics speak for themselves. By August 23, over 5,000 prisoners were taken, and, during the period August 18-21, the division had captured or destroyed 55 tanks and armored vehicles, 14 armored cars, 44 guns, 38 armored tracked vehicles for troop transport, 207 motor vehicles, and 152 horse-drawn vehicles. Polish casualties were posted as 325 killed, 1,002 wounded, and 114 missing.

The visible evidence left no doubt as to the scale of the carnage. In Eisenhower’s words: “The battlefield at Falaise was unquestionably one of the greatest killing fields of any of the war areas. Forty-eight hours after the closing of the gap I was conducted through the pocket on foot to witness scenes that could only be described by Dante. It was literally possible to walk for hundreds of yards at a time, stepping on nothing but dead and decaying flesh.”

Maczek’s material losses would soon be made good and, although the casualties of an army in exile are by definition difficult to replace, the Polish 1st Armoured Division continued to distinguish itself till the end of the war. It could be said that the action of the Poles at Mont Ormel had opened up the route to Paris just as their comrades who took the hill at Monte Cassino three months earlier opened up the route to Rome.

The events involving the closing of the Falaise Pocket have attracted their fair share of controversies, principally those that focus on why it was not closed sooner and the allocation of responsibilities for allowing a significant number of Germans to escape.

The familiar accusations arise about leaders’ egos, personality clashes, and the pursuit of national rather than Allied priorities, often forgetting that a highly mechanized and experienced enemy fighting for survival and surrounded on all sides is likely to be harder to stop than an army in a standard battlefield engagement.

Then there are the differences of opinion on how many actually escaped, usually agreed to be somewhere between 20,000 and 50,000, although one estimate puts the figure nearer 100,000. In contrast, the reader would find great difficulty in finding any variation of opinion regarding the way that the Polish 1st Armoured Division conducted itself.

Following the division’s success on The Mace and its contribution to the virtual destruction of the German Seventh Army and a large proportion of the 5th Panzers, it pursued German forces northwards following the coastline and liberated several large towns, including St. Omer, before continuing into Belgium and driving the Germans out of Ypres, Ghent, and other towns and cities.

On October 29, during Operation Pheasant, Maczek performed an outflanking maneuver to liberate the town of Breda without any civilian casualties. Subsequently a petition signed by 40,000 of the civilians gave him honorary citizenship of the town.

Next, Maczek’s division crossed into The Netherlands and eventually entered Germany in April 1945. On May 6, they seized the Kriegsmarine naval base in Wilhelmshaven, where Maczek received the surrender of the base, the East Frisian fleet, and 10 infantry divisions.

Immediately after Germany capitulated, Maczek was given charge of Polish I Corps and responsibility for all Polish forces in Britain; the Corps was disbanded in 1947.

Sadly, when the war in Europe came to a close and millions of civilians from several nations were celebrating the end of Nazi occupation, the Poles found themselves under the boot of another power. Many of those who had escaped to fight on the Allied side chose a life in exile rather than a return to the homeland they had risked their lives for and that had been turned into a Soviet satellite state. Not surprisingly, in 1989 it was Poland that eventually led the way out of Soviet control, displaying all the tenacity that had been its trademark 50 years earlier.

But, to add insult to injury, and despite all that they had done for Britain, the Poles were not invited to the huge 1946 London Victory Parade—a controversial move which was seen at the time as an appeasement of the Soviets.

Maczek chose to remain in the U.K. and made his home in Edinburgh, Scotland, where he worked as a waiter and bartender in a pub, a nearly forgotten figure. Since he had not fought in the British army, he was not entitled to a military pension. But in 1985, Maczek was invited to return to the city of Breda for the anniversary of its liberation and given a hero’s welcome.

He passed away in 1994 at the satisfying age of 102 and was buried in the Polish military cemetery in Breda alongside his men who had fallen in the fight to free the city. He had lived long enough to witness the raising of the Iron Curtain and the true liberation of his homeland, almost 45 years after the end of the war.