By David A. Norris

The Battle of Trafalgar, fought off the southwest coast of Spain on October 21, 1805, was a disaster for French Emperor Napoleon I. His Franco-Spanish fleet lost 21 of its 33 ships of the line captured and another sunk. Plans for a French invasion of England collapsed; British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger was elated.

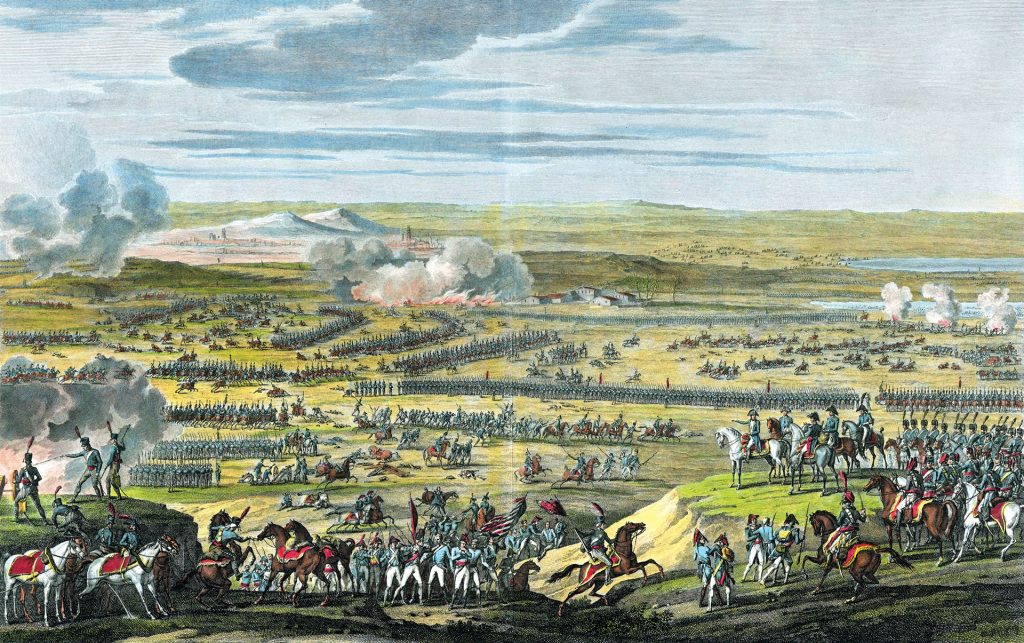

Yet several weeks later, news arrived in London to change Pitt’s optimistic joy into gloom. Trafalgar was a magnificent sea victory, but the December 2, 1805, Battle of Austerlitz balanced Britain’s advantage at sea by cementing Napoleon’s grasp of land power across Europe. “Roll up that map; it will not be wanted these 10 years,” Pitt told an aide, pointing to a large map of Europe in his office upon learning of Napoleon’s triumph at Austerlitz.

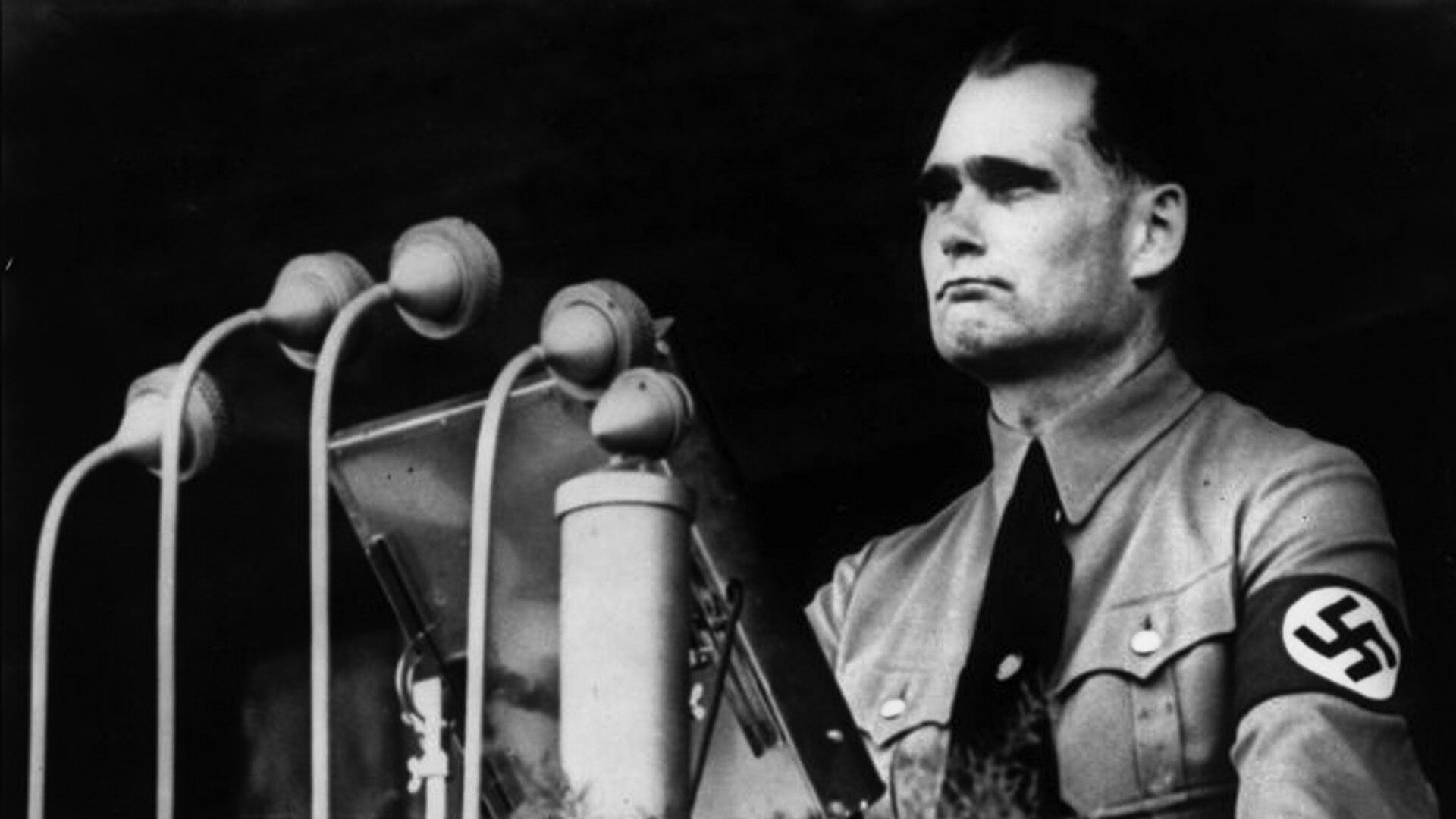

The 1802 Treaty of Amiens had brought only a short, shaky spell of peace before war resumed between Napoleon and Great Britain in May 1803. For a few months, some other European powers stayed out of the fighting. But in March 1804, Napoleon arrested Louis-Antoine, duc d’Enghien, a member of a branch of the Bourbon family who had formerly ruled France. False intelligence implicated the duke in a plot to assassinate Napoleon, who sent troops to seize the duke at his home in the neutral German state of Baden. After a sham trial, the duc d’Enghien was executed by firing squad.

To the crown heads of Europe, this was a sickening reminder of the bloody revolutionary purge of France’s royal family in 1793. They saw Napoleon as a menace to their regimes, especially after the former Corsican artillery officer declared himself emperor of France on May 18, 1804.

Pitt knitted together a new anti-French alliance, which became the Third Coalition. Joining the British by mid-1805 were Russia, the Hapsburg-ruled Holy Roman Empire, and Austria. The alliance also included lesser powers, such as Sweden, Sicily, and Naples.

Great Britain had few troops to spare, but its powerful navy menaced Napoleon at sea, and London sent financial aid to its European allies. Prussia hovered on the sidelines, reluctant to enter another war, leaving Austria and Russia to carry the burden.

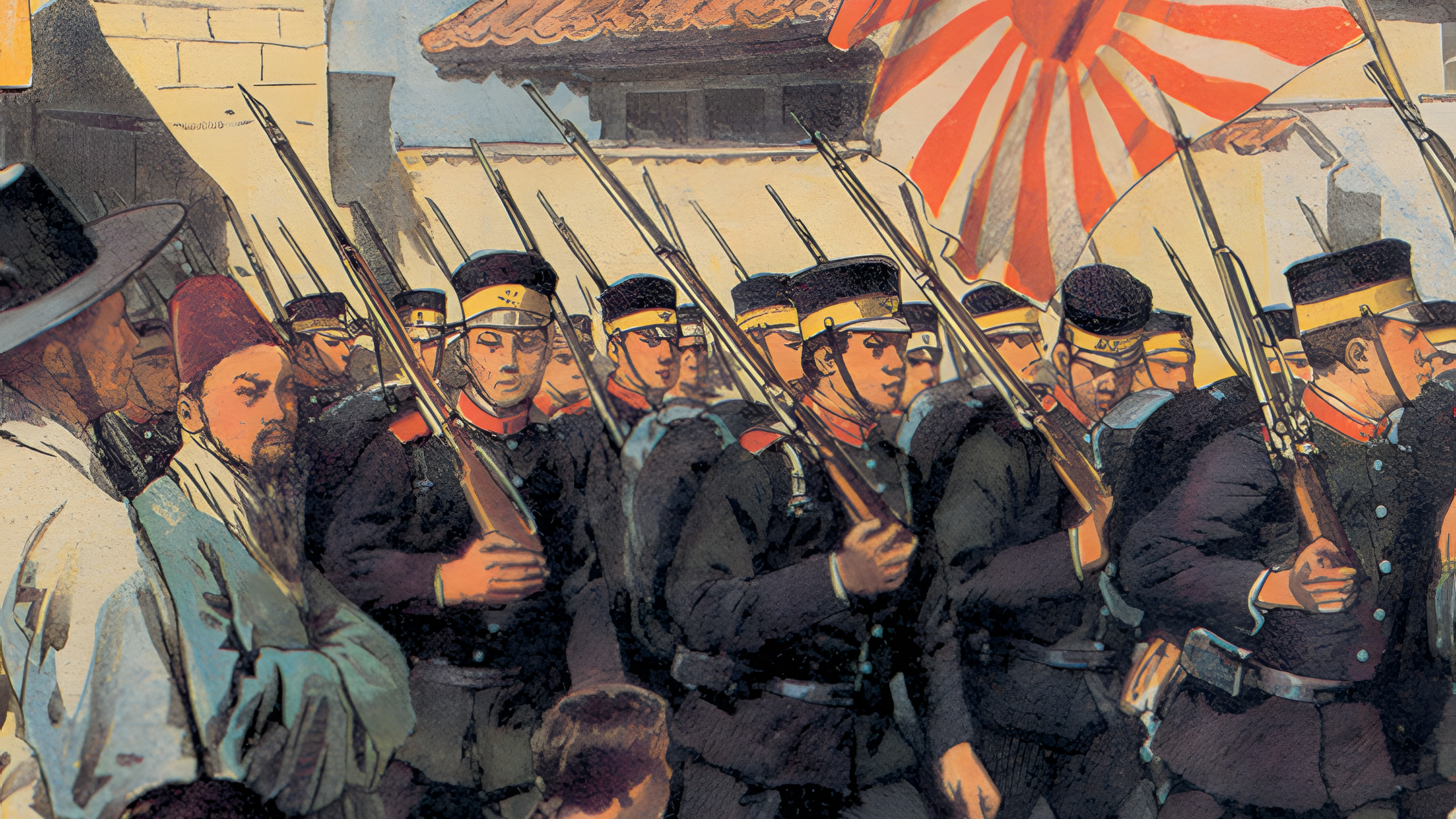

With two French armies assigned to guard Italy and France’s northeastern frontiers, Napoleon took the 150,000 men of his newly reorganized Grand Army across the Rhine. It was essential to deal with the Austrians first, before the Russians could march from the east and unite with them.

Part of the Grand Army crushed a smaller Austrian army under Karl Freiherr Mack von Leiberich at Ulm on October 17, 1805. Some of the Hapsburg army escaped, but on October 20 Mack surrendered nearly all his high command and 25,000 men. Since the Austrian officers gave their parole (formal promise not to engage in hostilities), they were barred under its terms from any further part in the campaign against the French.

Field Marshal Prince Mikhail Kutuzov, commanding the advancing Russians, knew nothing of Mack’s defeat until October 23. A forlorn traveler reached Kutuzov’s army at Braunau, in western Austria across the River Inn from Bavaria. The traveler was Mack himself, who delivered the grim news while on his way back to Vienna.

Mack’s fall from grace was complete. Forbidden to enter Vienna, he was compelled to give his report in a village outside the capital. The Austrians convened a court marshal. Mack not only lost his rank and honors, but also went to prison for two years.

Emperor Francis I of Austria, who was simultaneously Emperor Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire, instructed Kutuzov not to risk battle with the French. Instead, Kutuzov was to keep his army intact, withdraw to the east, and try to gather other coalition forces to augment his Austro-Russian army. French spymaster Karl Schulmeister, disguised as an Austrian officer, learned of the move and subsequently informed Napoleon that the Russians intended to avoid battle until reinforced.

The French won another victory at the Battle of Durenstein on November 11. During that minor clash, Allied chief of staff Johann Heinrich von Schmitt lost his life. The Austrian army, after Durenstein and the other sharp reverses of the previous weeks, waited to unite with the Russians before confronting Napoleon. They did not make a stand before Vienna, which fell to the French on November 13. Marshal Joachim Murat led the victorious troops into the Hapsburg capital. Schulmeister, whom the Austrians had arrested on suspicion of espionage, was freed by Murat’s arrival.

Kutuzov and his 65,000 troops fell back northward to Olmutz in Moravia. Tsar Alexander I and Emperor Francis I, along with several thousand Austrian troops, joined them. By November 25, they had 85,000 soldiers on hand.

Tsar Alexander had once admired Napoleon, but after the execution of d’Enghien he saw the French regime as a threat to the political order of Europe. While Francis I did not take an active role in command, Tsar Alexander—holding a vastly conceited opinion of his military abilities and leadership—took charge of the Russian forces himself. His entourage of aides and courtiers flattered him instead of guiding him. Some of his commanders favored continued withdrawal, perhaps into Hungary or Bohemia, until the coalition forces could regroup. But in late November Alexander, confidently but unwisely, dismissed advice from his cautious generals and made the decision to force a battle.

Maj. Gen. Franz von Weyrother replaced von Schmitt as chief of staff of the Allied armies. The 50-year-old had a mixed record but displayed a convincing facade of military mastery. He ingratiated himself with the Tsar and Russian commanders such as Friedrich Wilhelm, Count Buxhowden, and, for a time, with Kutuzov. The latter hoped von Weyrother would agree to move carefully. The new chief of staff, though, had different ideas. Von Weyrother favored a quick attack on the French, an opinion that suited the overconfident Tsar.

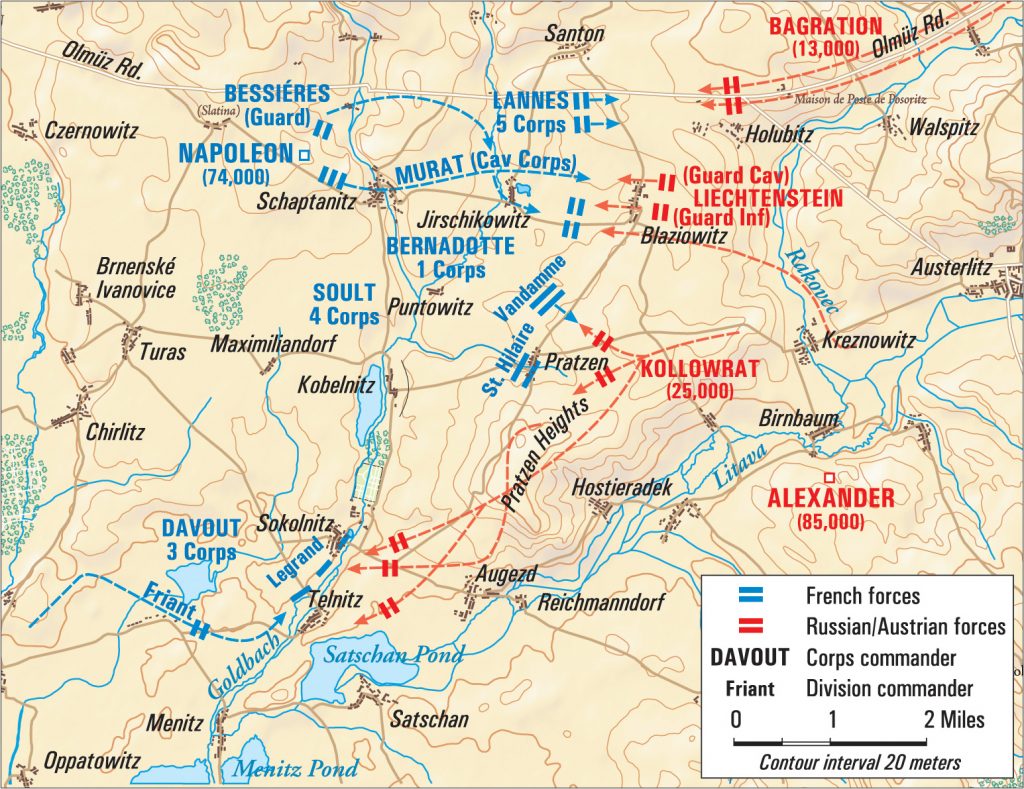

Leaving some troops to hold Vienna, Napoleon marched 47,000 men to positions around Brunn and Austerlitz. The Moravian village of Austerlitz, 80 miles north of Vienna, is now part of the Czech Republic and is known as Slavkov u Brna.

Two miles north of Austerlitz passed a road running west and east, between Brunn and Olmutz. To the west of Austerlitz were hills divided by the broad, low valleys of several brooks that flowed into a larger stream called the Goldbach. East of the Goldbach, the ground rose to a series of hills, including a plateau that was a commanding point of the terrain called the Pratzen Heights.

After exploring the terrain around the Goldbach, Napoleon ruled out ideas that would lead to ordinary victories. He saw a way to end the war in a single stroke. On November 28, he sent for all of the troops who could conceivably reach him in time for the crucial battle. Marshal Jean Bernadotte’s 13,000 men left Iglau, which was 50 miles west. In camp near Vienna, Louis-Nicolas Davout’s men received orders to march on the afternoon of November 29. At 9:00 pm General of Division Louis Friant’s troops were the first to leave camp. Davout and his staff rode ahead of the 6,000 marching troops.

On November 30, French troops briefly held the Pratzen Heights. To the utter surprise of his enemies, Napoleon abandoned this obviously commanding high ground and withdrew across the Goldbach. Believing the legendary French commander had made a mistake, the allies quickly occupied the plateau.

Napoleon had deliberately made the “error” of giving up the Pratzen Heights. He knew the enemy would rush to take the plateau, which certainly looked like a key piece of ground. He hoped that the coalition armies would then leave the Pratzen Heights to attack the French right.

Strategically, it was a tempting move for them; by doing so, the Allied armies could cut the French off from Vienna and any possible reinforcements to the south. Falling back to the north would put the French closer to the Prussian frontier 75 miles away. After a Russian and Austrian victory, Prussia might well drop its neutrality and pounce on a defeated French army.

At the end of November, to convey an impression of weakness and desperation, Napoleon twice requested personal conferences with Alexander I. The Tsar did not appear, but sent Prince Peter Dolgorukov in his place. Dolgorukov tactlessly frayed Napoleon’s patience by demanding that the French give up Italy immediately, or face the loss of other lands as well. Napoleon coldly dismissed the emissary. What began as a polite meeting ended with a menacing threat. “If you were on the heights of Montmartre, I would answer such impertinence with cannon balls!” Napoleon told the prince.

While the meeting seemed to accomplish nothing, it worked perfectly for the French. Napoleon met Dolgorukov near the perimeter of his lines, as if unwilling to let him see the condition of his army. Dolgorukov saw soldiers work on hasty entrenchments, and he glimpsed preparations for retreat, which were carefully staged for him. The prince returned believing that the French would collapse when confronted in the upcoming battle.

On the afternoon of December 1, Napoleon placed his headquarters atop a hill behind the French lines at Bellowitz, just south of the Olmutz Road. From the hilltop he could survey his own and the enemy’s camps. There was no structure available there, though, other than “a poor barn,” wrote the Baron de Marbot. “The emperor’s tables and maps were placed there, and he established himself in person by an immense fire, surrounded by his numerous staff and his guards.”

The French left flank began at the Bosenitzberg, a hill just north of the Olmutz Road. The French referred to the hill as the “Santon.” Entrenchments and artillery, added to the Santon’s already strong defensive position, encouraged the enemy to look elsewhere for a weak point to attack. So, it was even more likely they would strike the French right flank, just where Napoleon wanted them to attack.

From the Santon, the French lines ran south to the village of Jirschikowitz. Then the line swung toward the southwest around the Pratzen Heights. It followed the valley of the Goldbach and its tributaries, past the villages of Puntowitz, Kobelnitz, Sokolnitz, and Telnitz. Beyond the latter were the Satschan and the Menitz—two broad, shallow artificial fishponds.

Davout and his staff joined Napoleon on the afternoon of December 1. Friant’s division arrived at 7:00 pm after a forced march, having covered 80 miles in 46 hours. The troops halted at Raigern, five miles west of Telnitz. They rested a few hours before joining the troops at the front line early the next morning.

Napoleon’s right was held by General of Division Claude Juste-Alexandre-Louis, Comte de Legrand. Even with Davout’s men added, he would face nearly four times his numbers when the Austrians and Russians moved against him. In his favor, Legrand was a talented commander with fine veteran troops. The Goldbach itself was no more than a small creek, and foot soldiers could cross it nearly anywhere. But the stream coursed through boggy wetlands, and artillery could cross only at a few bridges at the villages. Legrand’s men, comfortably settled on high and dry ground beyond the stream, could fire down into the slow-moving infantry slogging through the bitterly cold water and mud along the stream.

Legrand only had to hold on; he was not expected to advance. With the right so thinly held, there were 16,000 men available in the center for Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult’s attack on the Pratzen. With the French holding the heights, they would cut the enemy forces in two and crush each section in detail.

Firing echoed from Telnitz after midnight as an Austrian attack drove the French from the village. Concerned that he had wrongly surmised the positions of the Allies, Napoleon rode with Soult and a party of staff officers to investigate. They were soon satisfied that the clash was only a minor affair.

It was in the early hours of the morning when Napoleon returned to camp. Instead of going back to bed, he decided to walk through the camps. His troops responded with a spectacular testimony of their devotion. First one man, then a dozen, and then hundreds wrapped straw around sturdy sticks and lit these improvised torches in their campfires. They cheered and saluted as Napoleon’s stroll swelled into a spontaneous torchlight procession.

The roar of this triumphal parade carried through the chilly air to the Allied lines, where pickets saw the glow of the blazing straw torches. Officers did not know what to make of this strange spectacle. The French were not leaving their camps, so the commotion did not signal a surprise night attack. Quiet returned at 2:00 am as Napoleon’s soldiers settled down to grab a bit more rest before the next day’s action. The only other action that night occurred when the French infantry drove away some Austrian cavalry and retook Telnitz.

Allied plans had been complete for several hours, after Von Weyrother held a nighttime meeting with his commanders. Most of the Austrians and Russians were distributed among five attacking columns and a reserve. Behind an advance guard of Austrians, two Russian columns would march southwest from the Pratzen Heights toward the villages of Sokolnitz and Telnitz. A third column, also of Russians, would unite with their right flank.

To their right, a combined Austrian and Russian column would push toward Kobelnitz. On the right of the Kobelnitz column, Prince John of Liechtenstein’s cavalry would hold the northern end of the heights below the Olmutz Road. North of the road was a Russian force under the capable Georgian-born Lt. Gen. Pyotr Bagration. Behind Liechtenstein was the reserve, under the Grand Duke Constantine, a younger brother of the Tsar.

Count Louis Alexandre Andrault de Langeron, a French royalist who had entered Russian service in 1790, recalled that the generals assembled at 1:00 am around a huge map of the area that was spread across a table. Von Weyrother “read us his dispositions in a very lofty tone, with an overbearing air, which plainly proclaimed a full persuasion of his own worth,” wrote Langeron. “We might really have been taken for a pack of schoolboys.” Kutuzov fell asleep during the briefing. At the end, Langeron tried to point out some drawbacks to the plans, but there was no debate, and the generals were sent back to their quarters.

Certainly, Langeron might well have questions about Von Weyrother’s overoptimistic plans. Von Weyrother intended a massive attack on Napoleon’s right at the cost of leaving the center depleted of troops, while their own right and left would be too far from each other to lend mutual aid. The overly complicated movements of the five columns were compounded by the language barrier between Russian- and German-speaking troops. Translating and copying the detailed orders for the generals took until 8:00 am the next morning, by which time tens of thousands of troops had already been in action for a couple of hours.

Most of all, the battle plan fatally depended on something that was very unlikely to happen, which was that Napoleon would become too paralyzed with shock and dismay to respond to enemy moves. Bagration, who was too far away on the flank to attend the pre-battle conference, knew his final orders only when they arrived well after dawn. “We shall lose the battle,” Bagration told his officers after reading the orders.

Bright stars sparkled in the clear, dark skies. Most of the troops in both armies waited or dozed in camps well below the hilltops and ridges. Down in the low ground, they were shrouded in thick fog. Sentinels could barely see comrades who were more than 10 yards away. Fog persisted even after daylight broke across the valley of the Goldbach.

The French generals gathered at 5:00 am for a final brief meeting to hone plans for the battle. Fighting threatened to break out between two of the emperor’s senior commanders. Marshal Jean Lannes had quarreled with Soult four days before. Lannes was so angry that he appointed a second, who delivered the challenge for a duel with Soult. They had not met since that moment. Although Napoleon forbade his officers to fight duels, Lannes expected to draw his sword against Soult that morning. Soult brushed off the challenge, and pointed out that there were more important matters to deal with. With the duel averted and last-minute orders given, the meeting broke up. Napoleon buckled on his sword. “Gentlemen, let us commence a memorable day!” he told his staff.

Von Weyrother set in motion the battle plan that Napoleon had hoped that the Allies would follow. Buxhowden led 40,000 men in the three columns menacing Legrand. Other than an Austrian advance guard under Lieutenant Field Marshal Michael von Kienmayer, the columns were Russian. Lt. Gen. Dimitri Doctorov commanded the first column, Lt. Gen. Count Louis Alexandre Andrault de Langeron commanded the second, and Lt. Gen. Ignacy Przybysewski, the third.

One of Legrand’s units, the 3rd Line Regiment, held Telnitz with two battalions of Corsican sharpshooters against Keinmayer’s Austrian advance troops. Walls and ditches along the fields and vineyards afforded valuable cover, but after suffering heavy losses, the 3rd Line Regiment was pried out of Telnitz. A regiment of dragoons came to support them, and soon afterwards General of Brigade Etienne Heudelet de Bierre arrived with some of Davout’s infantry. Together, the French units took back Telnitz. “The streets and houses were strewn with the dead,” recalled Davout. Three captured Russian guns were taken away, but the French had to leave other guns because there were not enough draft animals left alive to haul them. Heudelet’s 108th Line Regiment captured two enemy standards.

The defeated Russians had begun to discuss surrender terms. Meanwhile, Legrand’s 26th Line Regiment had been dispatched to Telnitz. They marched as far as the Goldbach and halted; they saw soldiers in the distance. The morning fog mixed with the smoke of battle led the 26th to mistake Heudelet’s men for Russians, and they opened fire on their own comrades. Amid the confusion, the battered Russians were reinforced by the first of arrivals of Buxhowden’s columns and rushed back to take Telnitz again.

It looked like the allies would turn the French right, but then Davout fell upon the Russians at Sokolnitz. Surprised while reordering their ranks after overrunning the village, the Russians were thrown back with the loss of half a dozen guns. Buxhowden sent in more troops, though, and recaptured Sokolnitz.

The mists began to dissipate at 8:30 am At first hilltops seemed to rise from the haze and looked like islands floating in a sea of fog. Then brilliant sunlight shone down on the French emperor and his staff. The magnificent drama and splendor of this moment was later immortalized in history and even poetry as “the sun of Austerlitz,” a glorious omen of victory.

The departing mists revealed the sight of the last coalition troops leaving the Pratzen Heights and moving toward Telnitz and Sokolnitz. Napoleon asked Soult how quickly he could reach the heights. It would take only 20 minutes, replied Soult. Napoleon decided to wait another 20 minutes before dispatching Soult. “When the enemy is making a false movement, we must take good care not to interrupt him,” said the French emperor.

A courier soon arrived from Legrand, bearing a warning that the enemy’s attacks had intensified along his front. With the enemy generals fully occupied, Napoleon ordered Soult to seize the heights, and he also ordered Lannes to advance against Bagration.

The fourth Allied column, with Austrians under Lieutenant Field Marshal Johann Kollowrat and Russians commanded by Lt. Gen. Mikhail Miloradovich, was already supposed to be on the plateau. These troops would have replaced the Russians who departed from the heights had the Allied staff made better plans, but Kollowrat was delayed while Prince John of Liechtenstein’s cavalry crossed his front riding northwest to join the Allied left.

Soult had two divisions ready to move, General of Division Dominique-Joseph Rene Vandamme’s on the left, and General of Division Louis St. Hilaire’s on the right. Both divisions were cloaked in the fog and smoke lingering in the lower ground until they stepped onto the Pratzen Heights. Their sudden appearance on the sunlit heights shocked the advancing allies, who had no idea that the French were so close.

Kutuzov, who with his headquarters staff accompanied the fourth column, realized the danger menacing the Allied center. The Allies could not afford to lose control of the Pratzen Heights. He recalled part of the second column, which was not yet engaged in the attacks around Telnitz, and ordered it to join Kollowrat and Miladorovich.

To meet the French, the fourth-column generals wheeled their men into battle formation and formed two lines. The sudden attacks by Vandamme and St. Hilaire smashed the first Allied line and sent the crumbled units reeling back into the rear line.

Kutuzov fed in all his remaining available troops, but he had no reserves available and the rest of his army was occupied elsewhere on the battlefield. Kutuzov and the French clashed for two hours on the plateau. Set afire by Russian guns, smoke rose from the burning village of Pratzen east of the heights. By 11:00 am, Soult’s divisions cleared the plateau for good, and Kutuzov pulled back toward Austerlitz, leaving behind several guns.

Soult’s action on the Pratzen Heights was a decisive phase of the battle. He not only crushed the Allied center, but also slashed the enemy force in two. Neither Bagration nor the forces embattled around Telnitz and the Goldbach could aid the other.

On the French left, Lannes pushed back Bagration on the Olmutz Road. Just to Lannes’ right, Marshal Jean Bernadotte and the cavalry of Marshal Joachim Murat maneuvered toward the village of Blaswitz. Liechtenstein’s cavalry should have met them, but they were late in moving to their position; instead, Bernadotte’s men fired into the Russian reserves under the Grand Duke Constantine.

Murat confronted the Russian Imperial Guard, but Prince Liechtenstein arrived with his Austrian cuirassiers, which broke up Murat’s charge. Keeping their momentum, the Austrian cuirassiers broke the first line of French foot and galloped through gaps in the formation of the second line.

Liechtenstein’s wild dash left his horses blown and his formation in disarray. At that point, Murat tore into them with fresh French cavalry. As the Austrians turned around, they passed between the fire of enemy artillery and blocks of infantry as Murat kept up fire from behind them. The headlong charge and the deadly flanking fire during the withdrawal decimated the cuirassiers. Lannes did not gain a decisive advantage, but he tied up the Allied right and kept their numbers away from the endangered center.

Vandamme’s first line broke under a bayonet charge by Russia’s Imperial Guard infantry at 11:00 am. His second line held and repulsed the guards. While the Russian infantry prepared for another charge, Grand Duke Constantine sent 15 squadrons of hussars and cuirassiers of the Russian Imperial Guard against Vandamme’s left flank. They smashed three French battalions and captured the imperial eagle standard of the 4th Regiment of the Line. Second-in-command of the 4th Regiment was Jerome Napoleon, the emperor’s youngest brother.

The Russian charge brought their men close to the base of the hilltop where Napoleon watched the battle. The French emperor committed two squadrons of the chasseurs of his Imperial Guard. Led by Colonel Francois-Louis de Morland, they smashed into the Semyenovski regiment of the Russian guard, breaking their square. But they could not hold on for long, as elements of the Preobrazhenski Regiment pressed toward them to relieve their comrades. The chasseurs were repelled, and two horsemen took the mortally wounded.

At that point, Napoleon committed more of his Imperial Guard. Led by Marshal Jean Baptiste Bessieres and General of Brigade Jean Rapp, six squadrons of elite chasseur and grenadier cavalry, two battalions of the guard’s horse artillery, and the emperor’s legendary company of Mameluke bodyguards galloped toward the Russians. “Soldiers! They are sabering our comrades; let us fly to their succor!” shouted Rapp.

Under the impact of the French charge, the Russian cuirassiers reeled back but rallied when joined by the Chevalier Guard. The latter was an elite unit of Russia’s army, of which it was said that even the privates were gentlemen.

Sabers flashed and blades clanged in a tremendous duel between the Imperial Guard cavalries of Napoleon and Alexander I. Nearby were the foot soldiers of the Russian Guard, but they could not fire into the melee without slaughtering as many of their own men as the enemy. Rapp, suffering from two saber cuts, realized that he had ridden ahead of his men. Russian horsemen surrounded him. Before he had time to react, a band of French chasseurs came to his aid; they hacked down or scattered the Russians and escorted Rapp to safety.

Mustafa, one of the Mamelukes, singled out the Grand Duke Constantine. Intent on capturing the Russian royal personage, Mustafa was foiled when the grand duke shot his horse with a pistol.

The French Imperial Guard soon got the upper hand over their enemy counterparts. The guardsmen swept the Russian horse and foot guards from the field, precipitating a chaotic retreat. Two hundred of the Chevalier Guards were captured, along with their commander, Prince Nikolai Repnin-Volkonsky, and several artillery pieces and standards.

Captain Louis-Francois Lejeune reported the news to Napoleon. Although the Russian cavalry was shattered, the Russian artillery still fired into the French. “The return was really more dangerous than the charge for the enemy pelted us with shells,” wrote Lejeune. “A chasseur of the Guard, who was already wounded, disappeared from my side with his horse, a shell having exploded inside the latter and blown both victims to pieces, leaving literally nothing but their shattered bones.”

During the morning, the Battle of Austerlitz had been a tense struggle, with the battle lines ebbing and flowing as each side sought a definitive advantage. But once the French had cleaved the Allied army in two, the Russians and Austrians tried desperately to stave off collapse and disaster and abandoned any aspirations for a victory. Under orders from Kutuzov, Kollowrat and Liechtenstein retreated to Austerlitz, well east of where their lines had been that morning.

The French drove back Bagration’s Russians along the Olmutz Road. Captain Lejeune wrote that the Russians had taken off their haversacks and piled them on the ground earlier that day. “Ten thousand haversacks ranged in rows remained in our possession,” wrote Lejeune. “But our booty, vast as it appeared, resolved itself into 10,000 little black boxes or rather triptych reliquaries, each containing an image of S. Christopher carrying the infant Savior over the water, with an equal number of pieces of black bread containing a good deal more straw and bran than barley or wheat.” Bagration eventually made it to Austerlitz, but the Olmutz Road was lost as a potential allied escape route.

In much greater danger were the divisions on the allied left. Soult and Davout, joined by the French reserves and Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, overwhelmed and captured much of Przybysewski’s third column.

French attacks cut off Buxhowden and several battalions from the rest of the army. Buxhowden’s contingent managed to get away, but 7,000 of the troops of Doctorov and Langeron laid down their arms and were made prisoners.

Some of these men escaped the French assault. Running from the field, they reached the frozen Satschan pond. A wooden bridge collapsed under a heavy gun, and a French shot blew up a caisson that rumbled along a narrow causeway. Shattered wreckage and dead horses blocked the causeway, which was the best avenue of escape. Soldiers stepped onto the frozen surface of the pond. They were soon followed by cavalry, as well as draft animals pulling field guns.

Later French accounts of the battle describe a horrific panorama, where the lake’s frosty surface was darkened with swarms of fleeing Russians. Napoleon’s artillery opened fire, lobbing solid shot onto the ice. The frozen surface cracked and shattered, and, so it was said, hundreds of soldiers and horses fell through into the frigid waters. Wild tales later circulated that thousands of doomed Russians and Austrians froze or drowned in the pond.

The reality for most of the men was less deadly. A few days later, the superintendent of the Menitz and Satschan fish ponds was ordered to drain them. His laborers found only two or three bodies in the Satschan, along with 150 dead horses and about 30 guns. Not a dead man or horse was found in the Menitz.

Evidently, the fleeing men and horses tried to cross the ice over shallow water near the shore. Any who crashed through the ice dropped into water that was not even waist-deep and managed to extract themselves. The superintendent’s report indicated that the few dead men were drivers or gunners, either entangled in the harnesses of lost guns or victims of French cannon shot.

The bright sun of Austerlitz was long gone as sleet mixed with light snow dusted the survivors who plodded away from the icy pond. No French pursuers harried them; the victors of Austerlitz were too exhausted, and their commands in too much disarray, to hurl them after the fleeing enemy.

Besides, there was no real need for close pursuit. At a cost of 9,000 casualties, Napoleon’s troops inflicted losses three times as heavy on the enemy. The Allies suffered 11,000 Russian and 4,000 Austrians dead. Nearly 12,000 of the Allies were prisoners.

Some 180 Allied guns were captured on the field. Drawing away these guns had proved impossible as wheels sank into the soft ground. “The Russian horses, which are more calculated for speed than for draft, could not drag them out of the deep clay, into which they had sunk,” wrote Maj. Gen. Karl Wilhelm von Stutterheim.

Alexander I and Francis I, and their shattered armies, were blocked from retreat northeast to Olmutz or southeast towards Hungary. Victorious French forces seemed to loom all around them. The two humbled emperors sent Prince Liechtenstein to negotiate a truce with Napoleon.

The Russians continued to retreat from the battlefield, but Emperor Francis lingered to sign what became the Treaty of Pressburg. Russia did not take an active part in the treaty, but the Tsar’s men were permitted to return home. Austria agreed to pay France 40 million francs. In addition, the Austrians confirmed French conquests in Italy, ceded Venice, and surrendered land to Napoleon’s German allies Bavaria, Wurttemberg, and Baden.

There was one final casualty of the Battle of Austerlitz. In 1806, Napoleon formed his client states into a new entity, the Confederation of the Rhine, forged from the ruins of the Holy Roman Empire. Austrian ruler Francis I had also held the throne of the Holy Roman Empire, in which he was rather confusingly known as Francis II. He abdicated the imperial throne, ending a chain of succession going back to Charlemagne, who was crowned in the year 800 as its first emperor.