By Nathan N. Prefer

The nation of Japan was hopeless before the invading force. They were outnumbered, and the enemy was about to land on the shores of the Imperial Home Islands. There was nothing left but to fight to the death against the savage invaders. But then, suddenly and without warning, a great wind came and destroyed the enemy fleet. The enemy, Mongols under Kublai Khan, had been destroyed by a sudden typhoon, a “Divine Wind” or “Kamikaze,” as it came to be known in Japanese history. In the year 1281, Japan had been saved by this help from above.

Nearly 700 years later, in 1944, the same situation faced Japan. It was not Mongols this time, but an enormous military force led by the United States that was threatening to invade Japan. The Western Allies had begun their inexorable advance against Japan three years earlier at New Guinea and Guadalcanal, and they were now more than halfway across the vast Pacific, aiming directly for Japan itself. In desperation, some Japanese leaders looked to another “Divine Wind” again to save them. This time, the Kamikaze would not be a typhoon, but swarms of suicide planes that were to be unleashed at the advancing allies.

The concept of individual suicide was accepted within Japanese society, particularly among those descended from the warrior, or Samurai, class. Suicide was generally accepted as the way to atone for failure, and ritual suicide, also known as seppuku and harakiri, was common among the military of Japan. It would appear repeatedly during the Pacific war, beginning at Guadalcanal and lasting to, and even after, Japan’s surrender.

But mass suicide was something else. Throughout the war, individual Japanese, particularly pilots whose planes were too badly damaged to return to base and being culturally unable to accept a surrender to the enemy, would fly their damaged aircraft into some enemy target, be it a ship or a ground target. These men were presumed to have been granted a direct passage to an honored place in heaven for their actions.

Suicide as a doctrinal military tactic, however, did not enter Japanese military policy until October 1944. By then, the Americans were invading the Philippines and the Palau Islands, threatening to cut off Japanese lines of supply from the Far East. Without those supplies, Japan could not sustain its war effort much longer. All attempts to stop the American advance had so far failed, and, as in 1281, Japan was growing increasingly desperate. Once again, the accepted solution was the Kamikaze.

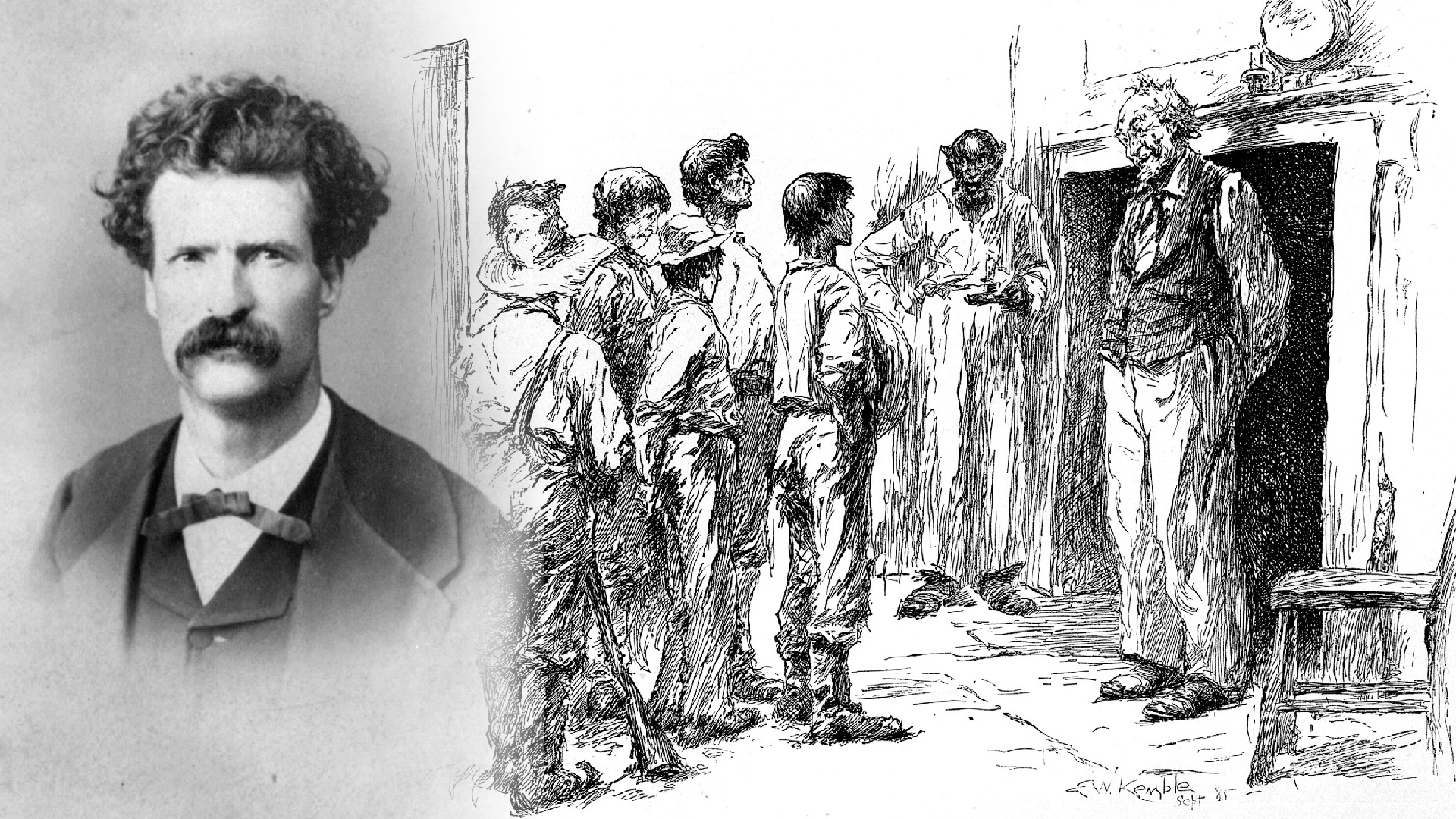

The origins of the modern Kamikaze are traced to Luzon, in the Philippines, in October 1944. The Americans were about to invade those islands, and the Japanese were preparing to meet that invasion. Captain Rikihei Inoguchi of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Forces was at Clark Field discussing attack plans against the approaching American invasion force. As a senior staff officer of the 1st Air Fleet, he had been assigned the job of organizing the air defenses of the Philippines.

While speaking with Commander Asaichi Tamai, commanding the 201st Air Group, he was joined suddenly by Vice Adm. Takijiro Ohnishi, the recently appointed commander of Japanese Naval Air Forces in the Philippines. Joined by some squadron leaders, the group sat down to listen to Admiral Ohnishi’s instructions.

Admiral Ohnishi was himself a pilot and a long-time advocate of naval aviation in Japan. He had helped plan the Pearl Harbor attack and had been a protégé of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. As a staff officer, Ohnishi had long been involved in discussions in Tokyo over the use of suicide operations, arguing against them. But the continued defeats in the Pacific and the loss of vital resource territory seemed to have changed his opinion by the time he was appointed to command the 1st Air Fleet in the Philippines.

Admiral Ohnishi began by stating the obvious: Japan’s situation was critical. He then explained that the Imperial Japanese Navy was about to launch an all-out attack on the American fleet off Leyte. But the Japanese fleet had no air cover of its own; the 1st Air Fleet on Luzon would have to provide that air cover. He had orders to protect the fleet for at least one week, keeping the American aircraft carriers from launching strikes that would cripple or destroy the oncoming Japanese fleet.

The problem was that the 1st Air Fleet had only 30 serviceable aircraft on Luzon. How could such a small force hold back the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of American planes coming to Leyte Gulf?

Admiral Ohnishi presented his solution. He told the assembled pilots and staff officers, “In my opinion, there is only one way of assuring that our meager strength will be effective to a maximum degree. That is to organize suicide attack units composed of Zero fighters armed with 250-kilogram bombs, with each plane to crash-dive into an enemy carrier…What do you think?”

Silence initially replied to the admiral’s proposal. Captain Inoguchi remembered, “No one spoke for a time, but Admiral Ohnishi’s words struck a spark in each of us. Indeed, ‘body-crashing’ (taiatari) tactics had already been used by Navy pilots in air-to-air combat against big enemy bombers, and there were many fliers in the combat air units who had urged that the same tactics be employed against enemy carriers.”

The group then discussed whether a fighter plane armed with a 250-kilogram bomb would be enough to disable or even sink an American aircraft carrier. They acknowledged that accuracy would be greater with a pilot guiding the weapon, including his own plane, to the target. Commander Tamai, the senior flying officer present, agreed that the plane and bomb together would be enough to at least disable any American aircraft carrier it hit.

Commander Tamai then held a meeting with his pilots, and came back to say, “The 201st Air Group will carry out his proposal. May I ask that you leave to us the organization of our crash-dive unit?” The Japanese Kamikaze program of 1944 had begun.

Commander Tamai assembled his enlisted pilots and explained the new proposal to them. Every one of the 23 pilots joyfully agreed to participate in the Kamikaze program. Returning to his staff, Commander Tanai and Captain Inoguchi discussed how best to organize the unit. They wanted an officer, preferably a graduate of the Japanese Naval Academy at Etajima, to lead the first attack.

After some discussion, Lieutenant Yukio Seki was selected as the attack leader. When approached by Inoguchi and Tamai, Lieutenant Seki responded, “You absolutely must let me do it.”

Discussions followed regarding the force’s organization. A name was suggested, and soon the new unit was called Shimpu, another Japanese word for Kamikaze. Admiral Ohnishi approved the plans, organization, and men for the new unit.

On the morning of October 20, 1944, the Shimpu attack group ate breakfast and then assembled for their final instructions. Admiral Ohnishi gave them a speech encouraging them to succeed, and the 24 pilots were prepared to go. But that was easier said than done.

The initial missions had to be aborted: mechanical failure grounded aircraft, enemy combat air patrols kept the Japanese grounded, and bad weather prevented takeoff. It wasn’t until the morning of October 25 that Lieutenant Seki and his group finally launched their mission.

The Shimpu encountered a support carrier group known to the Americans as “Taffy 3.” These Americans had already been attacked by Imperial Japanese Navy surface forces days earlier in Leyte Gulf. Now, one of the Shimpu group dove out of the sky at the escort aircraft carrier USS Kitkun Bay (CVE-71).

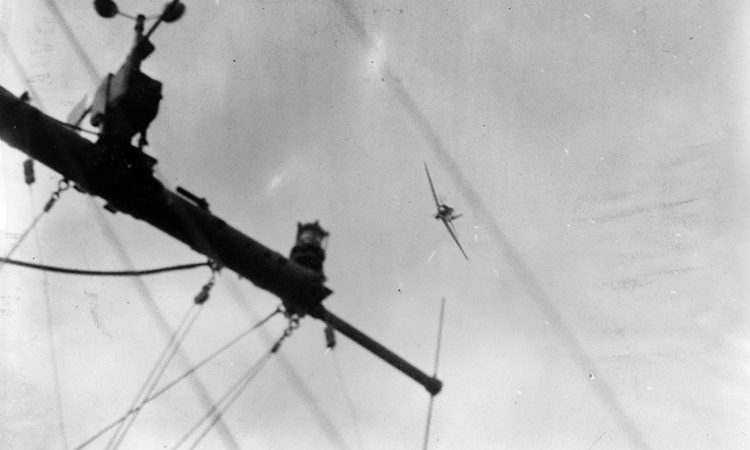

Sailor Ron Vaughn, an 18-year-old lookout on Kitkun Bay, spotted the plane as it climbed, rolled, and plunged down on his ship, aiming for its flight deck. The ship’s antiaircraft guns opened fire and damaged the plane as it dove. One round crumpled the tail section, causing it to veer off course. But the plane hit the water close aboard, damaging the ship and causing scores of casualties.

Another Shimpu pilot dove on the USS Kalinin Bay (CVE-68) and hit the deck of the carrier; two others were driven off by the antiaircraft fire.

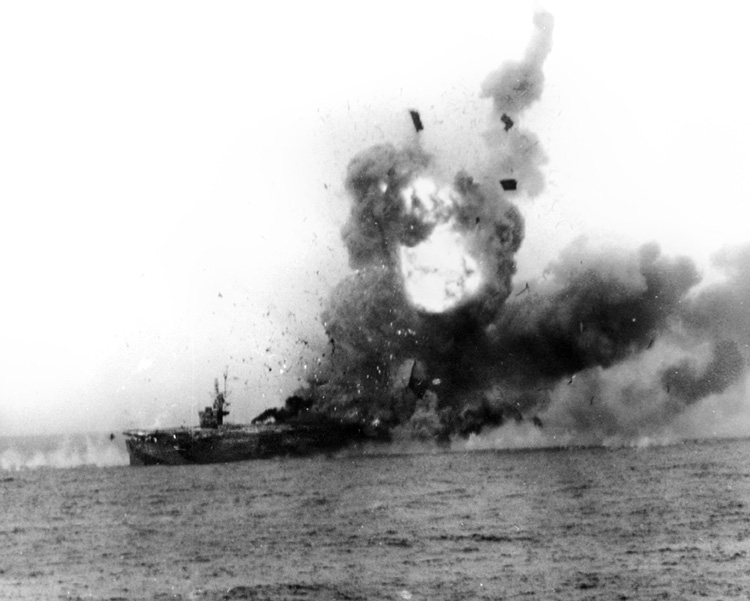

American fighter pilots immediately raced to the scene to defend their home carriers. Despite their efforts, three more Shimpu planes attacked the escort carrier USS St. Lo (CVE-63) from above; the first Japanese plane was shot down by fire from the St. Lo.

The second suffered the same fate, but this aircraft drew the American’s attention away from the third aircraft, which was following the ship and simply pulled up, nosed over, and crashed into the vessel. Witnesses remembered that the plane sliced through the flight deck, igniting fuel and ammunition in the hanger area below that deck. One sailor insisted that he saw a bomb drop from the aircraft an instant before the plane crashed into the ship.

The impact doomed the St. Lo. Explosions rocked the ship from bow to stern. Damage-control sailors raced around to save their ship, but it was no use. Thirty minutes after she was hit, the St. Lo sank. With her went 140 American sailors. She was the first “official” kill of the Kamikaze attack force.

Meanwhile, the Kalinin Bay was hit again and severely damaged; the USS White Plains (CVE-66) and USS Kitkun Bay were both narrowly missed. Although all these three ships were damaged, casualties remained few.

Ashore, the Japanese awaited the results of the first Kamikaze attack. Commander Tadashi Nakajima was at his base on Cebu Island when three Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter planes landed there. Out of the first to land came Chief Warrant Officer Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, who ran up to Commander Nakajima and made his report: Of the five Kamikazes and four escorts, he reported, Lieutenant Seki had hit a carrier, and a second Kamikaze hit the same ship, which soon sank. The third Kamikaze struck another carrier, setting it afire. The fourth plane crashed into a light cruiser which “sank instantly.” The fifth Kamikaze disappeared. Three of the four escorts managed to return to Cebu.

The report was a fiction. In fact, only the USS St. Lo was sunk, with the Kitkun Bay and White Plains damaged. No light cruiser was struck on October 25. This report, inaccurate as it was, was forwarded to Tokyo, which accepted it at face value and broadcast it to the Japanese nation as a great victory by the newly established Kamikaze Corps.

Believing a great success had been achieved from a small group of aircraft, the Kamikaze program continued on October 26. For the expenditure of five Kamikazes and two escorts, the light carrier USS Suwannee (CVE-27) was slightly damaged. Earlier, the USS Santee (CVE-29) had been damaged by a Kamikaze that approached so swiftly that no guns had been able to fire before it slammed into the ship.

By now, the standard operating procedure for the launching of Kamikazes had been established. First, they would await a report from a search plane that would locate, identify, and report on an American carrier group. Often, these reports were inaccurate, and a mission would have to be aborted when no ships were found by the Kamikaze pilots. Each Kamikaze flight had at least two escorting fighters to assist them in getting past the American combat air patrols that protected the American carrier battle groups.

Weather was, of course, always a factor. How many Kamikazes were assigned to any one mission depended upon the conditions reported by the scouts. Approaching their targets, the Kamikazes would increase their speed to make their approaches while the escorting fighters protected them from the combat air patrol. The signal, “All Planes Attack!” was given by the flight leader’s raised arm, and each pilot picked his own target, then plunged down toward it.

The deeds of the “Kamikaze Special Attack Corps,” one of the names for the new Kamikaze force, had by now reached Tokyo. Emperor Hirohito had responded to this new tactic with a message to his naval aviators through Admiral Ohnishi. The message read, “Was it necessary to go to this extreme? They certainly did a magnificent job.”

Captain Inoguchi, who was with Admiral Ohnishi in Manila, felt that the first sentence of the Emperor’s words were something of a criticism of Ohnishi’s new project, and Ohnishi appeared quite upset upon reading this message. But he remained determined to gain the Emperor’s favor by increasing his success.

Kamikaze strikes continued against American ships throughout the Philippine Campaign, including the invasion of Luzon and the clearing of the southern Philippines.

Meanwhile, the idea spread throughout the Imperial Japanese Navy and was taken up by the Imperial Japanese Army, as well. One of the chief reasons for this was the lack of skilled pilots. At the outbreak of the war, Japanese pilots had been the best of the best. But over the three years that the war had thus far progressed, attrition had whittled down those expert pilots to a precious few, many of whom where now busy training their replacements.

But the training of new pilots took time and fuel, neither of which the Japanese had in abundance. A Kamikaze pilot, though, did not need the in-depth training that a pre-war fighter pilot needed. He only needed to be able to take off, fly a distance, and crash into an enemy ship. Even formation flying was optional, although helpful.

As one historian has written, “Loss of aircraft and veteran pilots and shortages of fuel led to a reliance on suicidal Kamikaze units by 1944, made up of largely green, ill-trained aviators and a mélange of planes.”

The Kamikaze idea had by now spread far and wide among the Japanese military. Soon Kamikaze Corps were being established in Japan itself. Those forward bases under attack by the advancing Americans were often provided with some “Special Attack Units.” Soon this title was expanded to other suicidal methods of defeating the enemy.

One such method was known as the “Kaiten”—a manned suicide torpedo that was intended to sneak into American-held harbors and sink enemy ships at anchor. Then came the “Ohka” (Cherry Blossom)—a human-piloted bomb released from a carrying aircraft over the target and flown into that target by the pilot.

There were also suicide explosive speedboats (“Shin’yo” or Sea Quake)—small plywood craft filled with explosives and driven by a crew of one or two into enemy ships as they approached the shore of a Japanese base. Hundreds of these were later captured unused in the Philippines and Okinawa.

At the war’s end, near Okinawa, even the Imperial Japanese Navy’s super-battleship, the IJN Yamato, was turned into a form of Kamikaze. (See WWII Quarterly, Spring 2020.) But none of these other efforts achieved either the fame or the success of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s “Kamikaze Special Attack Corps.”

Some ships just seemed to draw the attention of the Kamikazes. One such ship was the Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Australia. Perhaps because her appearance different from that of American ships, she was hit repeatedly, although her near-identical sister ship, HMAS Shropshire, who often sailed alongside her, was never hit. Some called her “the Kamikaze Magnet.”

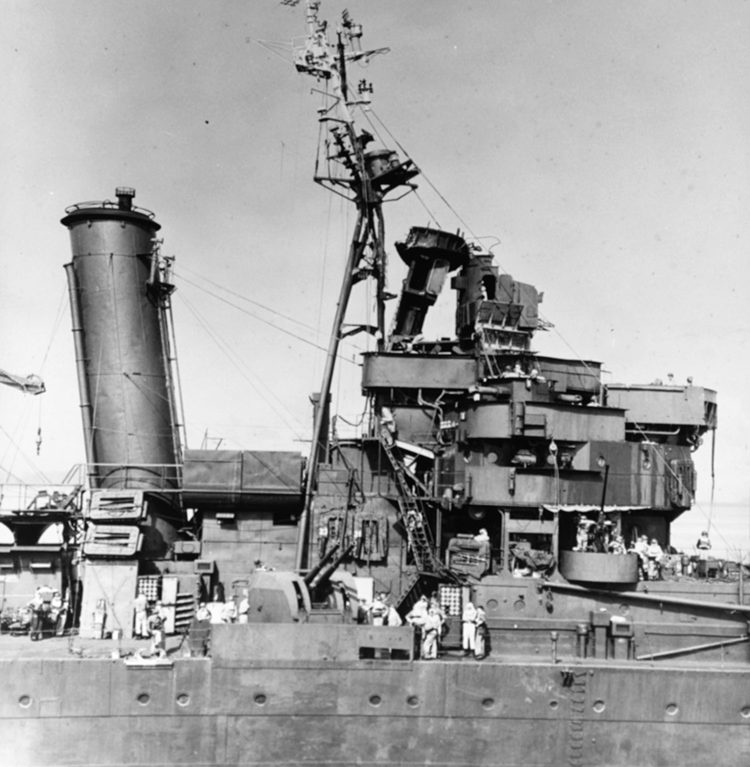

HMAS Australia had been in the war since the early days of 1939 and had earned herself an enviable battle record. But she just couldn’t seem to shake the Kamikazes. She was first targeted in Leyte Gulf on October 21, 1944, leading some Australians to claim that she was the first victim of the Kamikazes, and not the USS St. Lo.

That day, the attacking aircraft was seen to be hit by antiaircraft fire and almost crashed into the water. But the plane recovered, and despite further heavy antiaircraft fire, punched into the port side of the heavy cruiser. This sounds more like a “body-crashing” (Taiatari) tactic than a Kamikaze attack, but the strike cost the ship her captain, Captain Emile F. V. Dechaineux, along with five officers and 23 enlisted sailors. Scores of others were wounded.

The ship returned to the war after repairs in November, well after the Kamikaze had begun in earnest. In early January 1945, the HMAS Australia was attacked no less than five times by Kamikazes. On January 5, she was struck by a Zero, which hit her amidships; 25 men on the gun crews died and another 30 were wounded. Damage was slight, and she remained on station with a gunfire support group off Leyte.

The next day she was hit again, at the middle smokestack on the starboard side, killing 14 and wounding 26. Damage was minimal, and she remained on station. January 7 was a quiet day, but January 8 was not.

A Japanese bomber came in, chased by four fighters of the combat air patrol. The enemy went down barely 20 meters off the HMAS Australia’s port side. It skidded into the cruiser’s hull, but caused no damage or casualties. Less than 20 minutes later, another Japanese bomber appeared and repeated the same events. But this time, the bomb that the plane was carrying went off and ripped a large hole in the cruiser’s port side, flooding two compartments. Once again, there were no casualties. Asked if he wanted to withdraw for repairs, Captain J.M. Armstrong refused and remained on station.

By January 9, the Sixth U S. Army was wading ashore on the main Philippine Island of Luzon, and HMAS Australia was offshore in support. Eight Kamikazes came in searching for the invasion fleet, and two headed for the Australia. One of these hit the USS Mississippi (BB-41) and the other hit the Australia at her foremast, crushing her forward smokestack and rendering the forward fire room inoperable. With a hole in her side, her forward fire room out of action, and her speed reduced, the Australia had had enough. This time she accepted the offer to retire for repairs, once again with no additional casualties.

Kamikazes appeared in almost every battle after Leyte. But by far their most successful and deadly campaign came against the American invasion of Okinawa. Here, Marines and the soldiers of the Tenth U. S. Army faced a determined defense, one of whose primary objectives was to draw the American fleet into a position that would make it vulnerable for attacks from nearby Japan.

One of the negative by-products of rushing pilots through an abbreviated training program to qualify them as Kamikazes was that they had poor ship identification skills. This error was felt most by the “small boys”—the auxiliary ships that often accompanied the major fleet units to supply, fuel, and otherwise provide succor to them when needed.

These included some described by their titles, including LCS(L)3, or Landing Craft Support (Large) Mark 3. Developed from the original Landing Craft Infantry, or LCI, some had been modified with rockets, machine guns, 20mm and 40mm guns, and other assorted armament which, to the untrained Japanese pilot desperately trying to find a target while avoiding the combat air patrol and antiaircraft fire, were often mistaken for combat vessels such as destroyers and even cruisers. As a result, these flat-bottomed, diesel-powered, 160-foot-long ships often became the targets these Japanese pilots were seeking.

The U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet, under Admiral Raymond Spruance, was the largest in the world (535 warships), but its position at Okinawa was exposed. It was committed to the island for all manner of support and supply duties, which made its ships stationary targets for the Japanese, who no longer had to guess where the American fleet could be found.

To protect the fleet, the Americans had established a series of “radar picket” posts around the island to give early warning of the Japanese approach. Instead, these soon presented to the Japanese aviators’ lonely targets, ripe for attack. The radar-picket destroyers and destroyer escorts were supported by various “little boys,” which were known at these posts as “pall bearers,” since they spent so much time picking up survivors out of the water, making them an inviting target for the Japanese.

The Japanese reaction began slowly. On March 20, 1945, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters came up with a major offensive involving Kamikaze pilots called Ten-Goō(“Heavenly Operation”). Tasked with leading this operation was Vice Adm. Matome Ugaki, commander of the IJN Fifth Air Fleet.

After gathering every flyable plane he could find, no matter its obsolescence or original purpose, Ugaki assembled 3,000 of them at bases across Kyushu. The plan, dubbed Operation Kikusui, was simple: guided by the few experienced pilots Japan had left, the suicide pilots would be sent out in waves to find the American ships and destroy them. The veteran pilots would then return to their bases to pick up another group and repeat the process.

On April 6, 1945, the Japanese struck in force with Kikusui No. 1 against the U.S. Navy’s Task Force 58 and the British Royal Navy’s Task Force 57, the latter operating between Formosa and Okinawa. Some 700 planes—half of them suicide planes—took off and went hunting for the Allied fleets.

The first to be attacked at Okinawa were the destroyers USS Bush (DD-529) at picket station number 1, the Colhoun (DD-801) at picket station number 2, and the Cassin Young (DD-793) at picket station number 3. Although the three destroyers put up a deadly screen of antiaircraft fire, enough enemy planes got through to sink both the Bush and Colhoun; the Cassin Young barely escaped the same fate—for now.

Elsewhere, the destroyers USS Howorth (DD-592) and Hyman (DD-732) were severely damaged, while the destroyers USS Leutze (DD-481) and Morris (DD-417) were knocked out of the war. Destroyer USS Mullany (DD-528) was so badly damaged that she had to be scrapped. Destroyer USS Newcomb (DD-586) was also sent home for good, as was the USS Rodman (DD-456).

The list of sunken ships included LST-447 and support ships Logan Victory and Hobbs Victory. The minesweeper USS Defense (AM-317) went down as well. The USS Haynsworth (DD-700) was damaged, as was the USS Feiberling (DE-640). And this was only one day’s success for the Kamikazes.

The suicide pilots also tried attacking two American carriers, the Bennington (CV-20) and Belleau Wood (CV-24), but both ships escaped with minimal damage.

Both sides suffered badly during Kikusui No. 1. The Japanese had hit 17 American ships, sunk or knocked 11 out of the war, and killed over 360 sailors. The Japanese, in turn, had lost over 350 planes and pilots—planes and pilots that could not be replaced.

The next day the massive battleship IJN Yamato steamed toward Okinawa and her doom at the hands of the American pilots from Task Force 58.

The loss of Yamato did not stop the Japanese from continuing their suicide attacks on the Allied fleets. After suspending operations for a few days due to bad weather, on April 11, Kikusui No. 2 was launched—a two-day assault by 185 suicide planes accompanied by 150 escorts. The carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) was the first to feel the enemy’s sting, which knocked it out of action for two days while repairs were made. The carrier Essex (CV-9), too, was hit but not sunk.

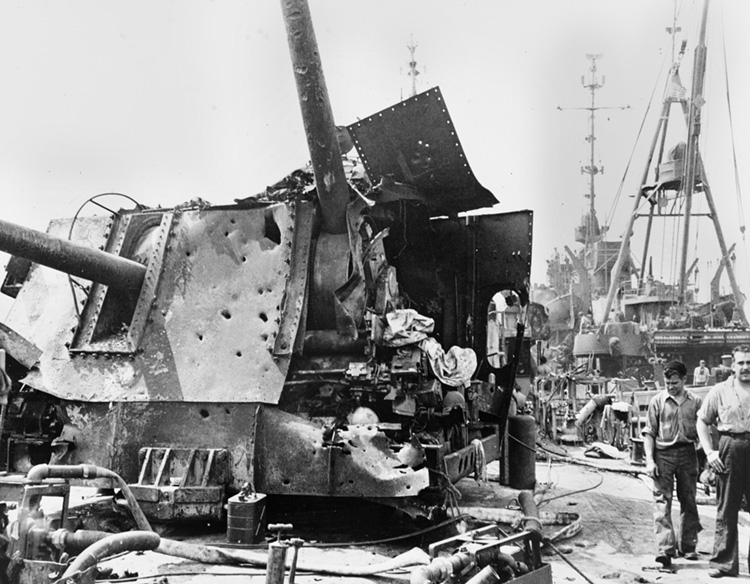

On April 12, another dozen ships were hit, with the destroyer USS Mannert L. Abele (DD-733) and LCS(L)-33 going down. On that same day, the Cassin Young was in the middle of the fight for her life, as she was targeted during a heavy Kamikaze raid. Her gunners shot down five aircraft, but a sixth crashed into her foremast, exploding in midair only 50 feet above the ship.

Surprisingly, only one man was killed, but 58 were wounded, many seriously. Although badly damaged, Cassin Young made it to Keramo Retto under her own power and would return to Okinawa in May after repairs. She would be attacked again in July, suffering major damage and loss of life, but she refused to be sunk. (The ship is today on display at the Charleston Navy Yard in Boston, Massachusetts.)

Each day, one or more ships were being hit and disabled, if not sunk. The radar picket posts were the most vulnerable, set far from other support and usually exposed to the incoming enemy air raids before anyone else. The raids went on daily throughout April, May, and June, and ship after ship was lost to the incessant aerial attacks.

CinCPac Admiral Chester W. Nimitz grew increasingly concerned and pushed Lt. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, commanding the Tenth U. S. Army, to move quickly to clear Okinawa of enemy resistance so that he could withdraw his ships from Japanese target practice. But the Japanese ashore were as determined as those in the air, and the battle continued well into June.

One the worst attacks by the Kamikazes was that suffered by the USS Laffey (DD-724), stationed at radar picket post number 1 on April 16. The first USS Laffey had been sunk during the naval battles for Guadalcanal. The current USS Laffey, laid down in 1942, had already established herself as a worthy successor to her namesake and had participated in the naval support during the landings in Normandy. On April 16, 1945, she would prove her worth once again.

Soon after dawn, 50 enemy planes were closing in on the fleet, and Laffey’s radar picked up four enemy planes approaching her. Three were shot down by Laffey’s antiaircraft fire, and the fourth was shot down by the guns on board Lieutenant Howell Chickering’s nearby LCS(L)-51. Carrier-borne Corsairs were slicing through the enemy formation, downing as many planes as they could.

A fifth plane attacked Laffey, only to be shot down as well. Then a sixth streaked in, strafing the ship as it approached. Several casualties resulted from the strafing before this plane crashed into the ship at the after funnel, jamming the fire-control radar.

A seventh aircraft smashed into the forward gun mount and then ricocheted off the ship, leaving no serious damage. An eighth plane was shot down as it attacked. But a ninth Zero used that attack to approach undetected and crashed into the starboard 20mm battery, damaging nearby 40mm batteries, starting a gasoline fire, and setting off the ammunition.

Almost immediately, a tenth plane hit the ship’s fantail, knocked out the aft 5-inch gun, and damaged three 20mm antiaircraft guns there. Plane number 11 dropped its bomb first near the depth-charge rails before crashing into the aft 5-inch gun mount, already damaged by a previous plane.

Plane number 12 dropped its bomb close aboard, jamming the rudder to a hard-left position. The Laffey now had no operable guns in the rear of the ship. The captain, Lt. Cmdr. Frederick J. Becton, now had a ship on fire and with no guns protecting her stern. The Japanese quickly took advantage of this weakness, and two more planes came in from astern, crashing again into the 5-inch mount number 53 and killing several of the crew who were fighting fires there.

Plane number 15 was shot out of the sky as it approached from the port quarter. A pursuing combat air patrol Corsair was so close on his heels that he hit the ship’s mast and ditched nearby. But this attack knocked out the ship’s radar.

Plane number 16 was next in line and was shot down over the ship by the combat air patrol, but not before its bomb shredded the ship’s bow with shrapnel, knocking out power to 5-inch mount 52, which continued to operate manually.

Plane number 17 was shot down, and plane number 18 was disintegrated by a shell from mount 52. Plane number 19 was also shot down, by mount number 51. A twentieth plane came in through the smoke off the Laffey and dropped its bomb on mount number 53 before breaking off the ship’s yardarm. It was then splashed by the combat air patrol.

Plane number 21 also dropped its bomb, knocking out two 20mm antiaircraft mounts before being shot down by the combat air patrol. A final attacker was also taken out by the combat air patrol.

The USS Laffey was miraculously still afloat but in serious trouble. It was down at the stern, the rudder was jammed, and most of its guns were disabled. Fortunately, the hull and engines had not been damaged. She had been hit by six Kamikazes, damaged by two other near misses, struck by three bombs, and had other close calls. She lost 31 killed and 72 wounded, but the fires were soon under control and the flooding stopped. She was towed to a repair base off Okinawa and, after service during the Korean War, would eventually end up as a memorial at Patriot’s Point, Charleston, South Carolina. Both LCS(L)s supporting her also survived, although with significant casualties.

But, like a swarm of angry wasps, the Kamikazes kept coming. As the battle progressed, their attacks and numbers began to thin out. Since Okinawa was lost and the next invasion would no doubt be at Japan itself, the Japanese decided to hoard their remaining Kamikaze planes and pilots for the final battle.

One of the greatest tragedies to befall the American fleet was that of the carrier USS Bunker Hill (CV-17), the flagship of Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher’s Task Force 58. On May 11, the carrier was on station 76 miles east of Okinawa when a Japanese “Zeke” fighter suddenly appeared out of the cloud cover.

Having just been refueled with nearly two million gallons of high-octane aviation fuel, the Bunker Hill was a floating Molotov cocktail waiting for a spark. The Zeke crashed into the flight deck, which was brimming with 30 planes waiting to take off; in the hangar deck below were 48 more that had been fueled and armed.

While the planes on deck exploded and burned, another Kamikaze dashed in and slammed into the ship’s control center, known as “the island.” Crewmen sprang into action in a valiant, but ultimately futile, effort to contain the blaze. Other ships pulled alongside to aid in the effort but they, too, stood no chance against the roaring inferno.

In the end, 346 officers and men out of the ship’s complement of 3,000 lost their lives, 43 were missing, and another 264 were injured. The charred wreck of the carrier managed to return for repairs to Bremerton, Washington, via Pearl Harbor, but it would never fight again.

At the end of the war, the Japanese themselves compiled a recapitulation of the record of the “Kamikaze Special Attack Corps.” They recorded that, of the 2,314 planes dispatched (including escorts), 1,086 returned. For the 1,228 planes “expended,” they claimed 81 ships sunk and 195 damaged, for a total of 276 ships.

Postwar records indicate that the correct figures are 34 ships sunk, including three light carriers and 13 destroyers. Of the 195 ships the Japanese claimed as damaged, they had actually damaged 288 ships, including 16 fleet aircraft carriers, three light carriers, and 17 escort carriers. It should be noted that several ships, like the HMAS Australia and USS Laffey, were hit repeatedly but not sunk. So, the Japanese claim of a total of 276 enemy ships sunk or damaged by Kamikazes is understated. In fact, they hit 322 allied ships, sinking 34. It was not the “Divine Wind” of 1281, but it was a respectable effort, nevertheless.

But, despite all her efforts to halt the American invasion of Okinawa, Japan had shot her bolt. Once Okinawa fell, she had very little chance of preventing a full-scale invasion of the Home Islands.

As the intelligence officer of the Fifth Fleet put it, “The Japanese are defeated, but we have not yet won the victory.”