By Roy Morris, Jr.

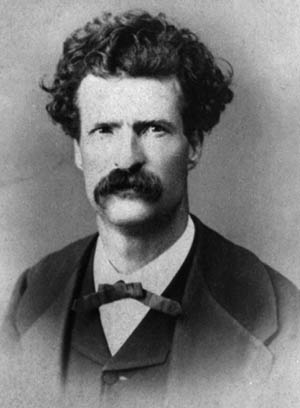

Twenty-five-year-old Mississippi River pilot Samuel Clemens (not yet known by his famous pen name, Mark Twain) was in his home port of New Orleans in late January 1861 when word reached the city that Louisiana had seceded from the Union. “Great rejoicing. Flags, Dixie, Soldiers,” he noted in his journal. It was something of an understatement from a brash young man who was not usually given to subtlety. He was, in fact, something of a chatterbox. “Taking you by and large,” Captain Horace Bixby told Clemens during his pilot’s training, “you do seem to be more different kinds of an ass than any creature I ever saw before.” Countless others shared that opinion.

A native of border-state Missouri, Clemens was one of the few Americans at the time who had no strong feelings about the issue of secession—or slavery either, for that matter. His piloting work on the Mississippi had inevitably exposed him to slavery in all its myriad forms, from dockworkers staggering under passengers’ luggage to field hands stoop-picking cotton on the great plantations along the river, but he paid it little mind. His focus was on the river, on the steamboats he piloted up and down its notoriously fickle length as one of “the only unfettered and entirely independent human being[s] that lived on the earth.” He fully intended “to follow the river the rest of my days, and die at the wheel when my mission was ended.” And then, as Abraham Lincoln would say with eloquent simplicity a few years later, the war came. Nothing would ever be the same, for Sam Clemens or the rest of his contentious fellow citizens.

Warning Shots Across the Bow

Hitching a ride north on his friend Zeb Leavenworth’s riverboat Nebraska, Clemens was relaxing on the bridge of the boat when Union forces at Jefferson Barracks below St. Louis fired a warning shot across Nebraska’s bow, then followed with another blast that crashed into the pilothouse, splintering wood and glass about the cabin and sending the young men sprawling to the floor. “Good Lord Almighty!” shouted Leavenworth. “Sam, what do they mean by that?” “I guess they want us to wait a minute, Zeb,” Clemens responded—calmly and coolly, or so he claimed many years later.

Hitching a ride north on his friend Zeb Leavenworth’s riverboat Nebraska, Clemens was relaxing on the bridge of the boat when Union forces at Jefferson Barracks below St. Louis fired a warning shot across Nebraska’s bow, then followed with another blast that crashed into the pilothouse, splintering wood and glass about the cabin and sending the young men sprawling to the floor. “Good Lord Almighty!” shouted Leavenworth. “Sam, what do they mean by that?” “I guess they want us to wait a minute, Zeb,” Clemens responded—calmly and coolly, or so he claimed many years later.

Later that month, Clemens returned to his hometown, Hannibal, Missouri, to collect an outstanding $300 debt from his friend and fellow riverboat pilot, Will Bowen. The previous winter the two had come to blows—not a usual occurrence for the pacifistic and ardently neutral Clemens—over Bowen’s overt “secesh” talk. Now all was forgotten, and the two friends attempted to resume their carefree boyhood habits in a town suddenly controlled by Union-leaning Home Guards who elbowed citizens off the sidewalk and filled the air with raucous patriotic songs. It was almost enough to turn one into a Confederate—almost, but not quite.

His Brush With the Union

One afternoon, Clemens was slouching about the levee down by the river with Sam Bowen, Will’s younger brother, and another out-of-work pilot, Absalom “Ab” Grimes, when an arriving steamboat slid into place, unloading a troop of blue-clad soldiers and a spruce young lieutenant who immediately demanded to know their identities. The trio told him their names and the officer brusquely informed them that they were being drafted into the Union Army. He would take them back to St. Louis himself. It was Clemens’s worst nightmare suddenly come to life.

After a quick trip back downriver aboard the Harry Johnson, the dispirited trio was escorted into the headquarters of Brig. Gen. John B. Grey, commander of the Union District of St. Louis. Appealing to their patriotism—what there was of it—Grey told Clemens and the others that their skills were needed by their country to guide Union troopships up the Missouri River. When the reluctant warriors argued that they only knew the Mississippi River, Grey responded, “You could follow another boat up the Missouri River if she had a Missouri pilot on her, could you not?” They admitted that they could. “That is all that is necessary,” said the general, preparing to sign the official paperwork.

“We stood there shaking in our boots, seeing our bodies at the bottom of the treacherous Missouri,” Grimes recalled. “We were mad and desperate.” Fortunately for the three reluctant pilots, Grey was interrupted just then by the arrival of a pair of stylishly dressed young women. While he was distracted, the men slipped out the side door and hightailed it back to Hannibal. Their unwanted brush with the Union Army had the effect of driving them into the waiting arms the Confederate Army—or what passed for it in backwoods Missouri, the newly formed Marion Rangers.

The Marion Rangers

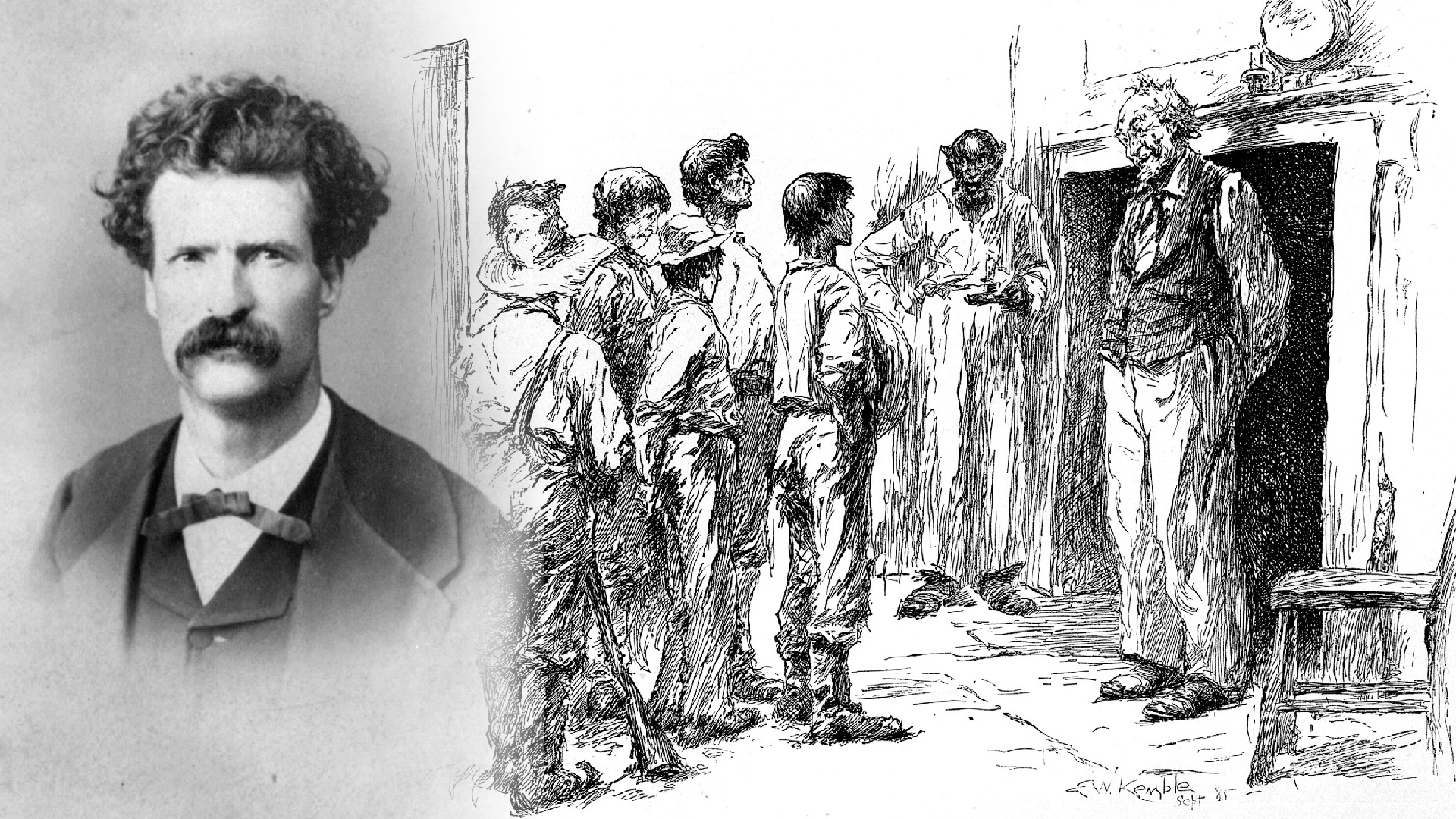

Named for their home county, the Marion Rangers were the brainchild of local attorney John Robards, who had begun calling himself Captain RoBards since he thought it sounded more military. The company consisted of only 15 members, including the latest three recruits. They all gathered in late June at the farm of Mexican War veteran John Ralls, a former colonel who swore them into service in the name of Missouri governor Claiborne Jackson, who had formed a pro-Confederate legislature in the southern part of the state after being driven from the capital in Jefferson City. The Rangers then held an open election of officers. William Ely was elected captain, Asa Glascock was first lieutenant, Sam Clemens was second lieutenant, and Sam Bowen was first sergeant. By the time they were through voting each other high-ranking positions in the company, there were only three or four men left over to serve as privates. It was probably just as well, since none of the new soldiers deigned to take orders from anyone else. They had all known each other since they were boys.

Clemens rode to war atop a fractious yellow mule he called “Paint Brush,” carrying with him a valise, a carpetbag, a pair of blankets, a quilt, a frying plan, an old-fashioned Kentucky squirrel rifle, 20 yards of rope, and a canvas umbrella (the natural redhead was prone to sunburn). It was enough, he thought, to tide him over for the next three months, which was about how long he thought the war would last. The other Rangers were equally well outfitted. Since no one had been issued an official Confederate uniform, they made do with a variety of plaid hunting shirts, green overcoats, white linen dusters, and denim jackets. Most carried a big Bowie knife and proceeded to chop off each other’s hair with a pair of rusty sheep shears to get ready for the close-quarter, eye-gouging, hand-to-hand combat they expected to encounter with desperate enemy soldiers lurking behind every rock or bush in northeastern Missouri.

Before fighting to the death with imaginary Union foes, the Rangers’ first order of business was selecting a comfortable place to camp, preferably with a handy swimming hole and abundant fish to catch for dinner. Clemens, impressively belted and sheathed with a Mexican War sword belonging to Colonel Ralls’s old brother in arms, Colonel Brown, led the company to an abandoned maple sugar camp, which he described as “a shady and pleasant piece of woods on the border of the far-reaching expanses of a flowery prairie. It was an enchanting region for war—our kind of war.” Half the men immediately jumped into the creek to go swimming; the other half broke out their fishing poles. They called their bivouac Camp Ralls.

Life Among the “Rangers”

Once safely installed in camp, the Rangers set about learning to ride the horses and mules they had brought with them. “We did learn to ride, after some days’ practice,” Clemens would recall, “but never well. We could not learn to like our animals.” His own mule, Paint Brush, threw him at every opportunity, and Bowen’s horse bit Bowen on the leg whenever—and it was often—it sensed him falling asleep in the saddle. When 2nd Lt. Clemens ordered 1st Sgt. Bowen to feed his mule for him, Bowen responded “that if I reckoned he went to war to be a dry-nurse to a mule, it wouldn’t take me very long to find out my mistake.” One night a well-lubricated Ranger named Dave Young accidentally shot and killed his own horse, which had failed to give the proper password. Ab Grimes cut down a clump of snapdragons with a blast from his double-barrel shotgun. Everyone in camp was a little on edge.

The Rangers moved about frequently, seeking to avoid any actual contact with the enemy—particularly a large Union force led by a freshly minted colonel named Ulysses S. Grant, who had taken over command of the 21st Illinois Infantry about the same time the Marion Rangers came into being. The Rangers, in fact, did so much marching and countermarching that a skeptical farmer in the area observed dryly that the Rangers would undoubtedly win the war all by themselves, “because no government could stand the expense of the shoe-leather we should cost it trying to follow us around.”

Moving to a less salubrious location they dubbed Camp Devastation, the Rangers stood for a formal inspection by the new district commander, Colonel Thomas A. Harris, a fellow Hannibal resident who had been the local postmaster before the war. Harris, said Sam Clemens, “was a first-rate fellow, and well liked, but we had all familiarly known him as the sole and modest-salaried operator in our telegraph office, where he had to send about one dispatch a week in ordinary times, and two when there was a rush of business.” Harris had no more luck issuing orders to the Rangers than any of the other officers—which is to say, none.

A few days later, pronouncing himself “incapacitated by fatigue from persistent retreating,” Clemens left the Marion Rangers and returned to his sister Pamela’s home in St. Louis. By then, he said, “I knew more about retreating than the man that invented retreating.” Once again he stayed close to home, dodging recruiting officers and Confederate provost marshals. Technically, he was AWOL, although it is doubtful that anyone had reported him, or if so, that such reports had been forwarded on to St. Louis. The war was still a confusing affair, and the absence of one obscure member of an equally obscure militia company was unlikely to have been noticed by anyone.

Recalling His War Record & Meeting Ulysses S. Grant

Recounting the two or three weeks he spent campaigning, Twain later portrayed it as a fun-filled lark. Writing for a predominantly Northern audience, the author sought to downplay his apostasy to the Union. On 15 separate occasions, he described himself and the other Rangers as “boys” “youths,” “children,” or “school-boys.” He was nearly 26 at the time, but as Huck Finn might have said, “That ain’t no matter.” Besides, Twain strongly implied, it was not an actual rebellion from the Union cause, but merely a handy excuse for a Tom Sawyeresque romp in the northern Missouri countryside. He made much of the fact that Ulysses S. Grant had been in the general vicinity at the same time—even considered calling his article “My Campaign Against Grant.” In fact, Grant remained a good deal north of the Rangers’ general area of operations, although, ironically enough, he did pass through the tiny hamlet of Florida, Missouri, where Twain had been born.

As fate would have it, Twain would eventually gain an opportunity to meet Grant. In late 1884, he convinced the general to publish his memoirs with the author’s own publishing company, Charles L. Webster and Company. Conferring frequently with Grant at his home on 66th Street in New York City, Twain on at least one occasion brought up the comical near-overlapping of their Civil War careers. “Today talked with General Grant about his & my first Missouri campaign in 1861,” Twain noted in his journal. “He surprised an empty camp near Florida, Mo., on Salt River, which I had been occupying a day or two before. How near he came to playing the devil with his future publisher!” Ultimately, Grant would complete his memoirs, and after the general’s death in 1885, Twain presented Mrs. Grant with a royalty check for $200,000—the largest single payment, to the point, in American publishing history.

Mr. Morris, I thoroughly enjoyed your article on the Marion Rangers. My great great grand uncle Charley Mills was a Marion Ranger. I am writing to see if you know anything about the Marion Rangers muster roll. I have heard it exists but haven’t been able to find it. I would so love to obtain a copy in print or online. Can you help? Jane

To Jane Phillips:

How is your research going on the Marion Rangers? I am curious to know what you have found.

Thank you,

Lonnie R. Clemens