By Walter S. Zapotoczny, Jr.

The Battle of the Bulge lasted from December 16, 1944, until January 25, 1945, and stands as one of the classic stories of true grit and defiance against a strong and determined enemy.

Much has been written about the 101st Airborne Division’s heroic defense of Bastogne. However, another unit gets little attention from historians: Colonel Hurley E. Fuller’s 110th Regimental Combat Team of the 28th Infantry Division, originally the Pennsylvania National Guard. Without their brave stand at the onset of the German offensive, the 101st Airborne might not have reached Bastogne in time.

German intelligence had done a good job of determining the American forces opposing Hitler’s forces. At the dividing line between Lt. Gen. Miles C. Dempsey’s Second British Army and Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ First U.S. Army in the northwest of Aachen stood the troops of Maj. Gen. Alvan C. Gillem, Jr.’s XIII Corps; Maj. Gen. Raymond S. McLain’s XIX Corps; Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins’s VII Corps; and Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow’s V Corps, with the 18th Cavalry Squadron and the 99th Infantry Division thinly spread across 19 miles of the Belgian-German border.

South of the Schnee Eifel, and right in the bull’s-eye of General Erich Brandenburger’s Seventh German Army’s objective area, Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps occupied positions next to the Our River alongside the 106th Division’s 424th Infantry Regiment, and to its south, the 28th Infantry Division.

Many of the men who had been with the 28th since it landed in Normandy on July 22, 1944, were wrapping themselves in wool blankets and huddling around fires to keep warm, struggling to recall the day in August, four months earlier, when they had paraded through the streets of Paris to the cheers of millions. The division was immediately packed up and trucked to the rapidly moving front to the east, where it became the first American division to crack—temporarily—the Siegfried Line, or West Wall. Then came the horror of the Hürtgen Forest.

After suffering more than 6,000 casualties in heavy fighting in the Hürtgen Forest during the autumn of 1944, Maj. Gen. Norman Cota’s 28th “Keystone” Division was sent to an area that First Army thought would be a quiet sector to rest and replace their losses.

The division was spread out along a 30-mile front on the west bank of the Our River in Luxembourg. While 30 miles was about three times the amount of ground an infantry division could be reasonably expected to cover, no one at higher headquarters seemed too worried. The Germans were, after all, as good as beaten.

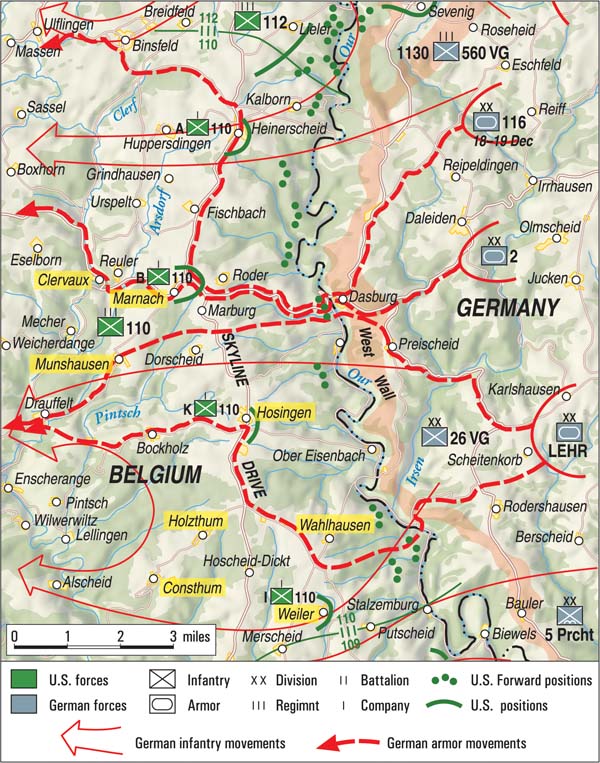

The division’s three regiments were in a line, with the 112th, 110th, and 109th Infantry Regiments aligned north to south. But only the 1st (Lt. Col. Donald Paul) and 3rd (Major Harold Milton) Battalions of the 110th were on the line, while the remaining 2nd Battalion (Lt. Col. Ross C. Henbest) was held in division reserve at Doennange and Wiltz, eight miles to the southwest.

The 110th had six company-sized strongpoints composed of infantry troops and engineers on either side of a ridge flanked by the Our River on the east and the Clerf River to the west, which the GIs called “Skyline Drive.” Along the ridge ran the St.Vith-Diekirch Highway, a road that led directly from St. Vith in the north to Bastogne. The fight for the many villages along this route would soon become known as the Battle of Skyline Drive.

No one knew that German dictator Adolf Hitler had ordered a massive counteroffensive against American and British forces gathering on Germany’s western border and had placed the entire 200,000-man operation, the goal of which was to plunge through the supposedly “impenetrable” Ardennes Forest, in the hands of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt.

In the early morning hours of December 16, 1944, General Josef “Sepp” Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army, along with General Heinrich von Lüttwitz’s XLVII Panzer Corps of General Hasso-Eccard von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army, shattered the quiet with tremendous artillery barrages, followed by infantry and armor attacks all along the front.

The 110th Infantry was in the center of the 28th Division line, and Cota knew that the center had to hold or all would be lost. He called Fuller and told him in no uncertain terms, “No one comes back.” Fuller knew what that meant. “No one comes back, sir,” he replied to Cota.

All across the Keystone Division’s front, men began the painful art of trading space for time.

From the moment the first German artillery rounds began to fall onto their positions, the Americans knew they were in for hard times. The Battle of the Bulge had begun. Lüttwitz was throwing more than 200 tanks and 27,000 men at the 5,000-man 110th Infantry Regiment.

William Shapiro, a medic in the 110th Infantry, recalled, “We were on the … Skyline Drive near Marnach. After digging in with several infantrymen around me, we just laid there, awaiting orders…. The high ridge road blocked our view in front of us. We could not see the Our River, which the Germans had to cross to enter Luxembourg. It was all quiet, and it was dawn. Suddenly, there was a tremendous barrage of German artillery from across the river.

“Despite the knowledge that I was expecting it to occur, the sudden loudness and massive amounts of flashes lighting up the sky on the other side of the river shocks you into reality. You hear many repeating explosions as the shells land one after the other. The machine-gun firings, mortar shell bursts, and ‘Screaming Meemies’ are all about you as you dig deeper and deeper into your foxhole. You are helpless and alone.”

Suddenly, a shell went off near Shapiro, knocking him unconscious. Although evacuated to an aid station, he was soon taken prisoner and would spend the rest of the war as a POW.

The attack was so intense that by the time word of the assault reached Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group headquarters at 10:30 that morning, several of the 110th’s small outposts were fighting for their lives as they took the brunt of Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army attack. Spread so thinly over so much ground, many of the men of the 110th were surrounded. Adding to their peril was the coldest European winter in centuries. Some of the veterans recalled, “God, was it cold! If a canteen was left outside just a few minutes, it would freeze. So would wet feet, and all of us had a pair of them.”

From 5:30 on the morning of December 16 until some time in the afternoon of the 18th, the soldiers of the 110th Regimental Combat Team fought and held, giving ground only when forced out, all the while buying time for General Dwight D. Eisenhower to find and move reserves forward from deep in France. At the onset of the Battle of the Bulge, General Bradley did not have one division in reserve due to the fact that the U.S. Army was so short of manpower. The few units that could be found had to be alerted, procure transportation, load their equipment, and moved into position behind the overwhelmed—but still holding—thin 28th Division line.

Determined to preserve the details of the battles, the Cercle d’Études sur la Bataille des Ardennes (Study Group on the Battle of the Bulge, or CEBA) in Luxembourg was formed shortly after the war. The group disseminates information on all aspects of the Battle of the Bulge and provides educational materials for schools and students of history. Many CEBA members were in the Luxembourg villages at the time of the battles. The following are summaries from CEBA’s records of the 110th Regimental Combat Team’s actions in eight Luxembourg villages beginning on December 16, 1944.

26th Volksgrenadier Division attacks Weiler

In the small village of Weiler, Company I of the 3rd/110th Infantry (less its 1st Platoon) was in its defensive positions when the offensive by the 26th Volksgrenadier Division began. Soon after the enormous deluge of artillery fire fell on the village, the first Germans approached the village. The resistance of Company I was so fierce and savage that the Germans twice asked for and were given permission to send stretcher-bearers to pick up the wounded under a white flag. The battle had to be interrupted twice thereafter.

Around 1:30 PM, the defenders of Weiler were amazed to see another German soldier approaching the village, carrying a white flag. The emissary asked that the village be honorably surrendered. The defenders, who were waiting for tank support, refused. When late in the evening those tanks had not arrived, the brave American defenders ran into difficulties, for their situation had grown worse every hour. The situation became desperate when the ammunition was practically exhausted; however, the surviving defenders continued to fight on into the night.

Although the German 26th Volksgrenadier Division’s strength was overwhelming, the brave men of Company I defended the village of Weiler—not only on the first day but also during the day of December 17—as if it was their own hometown. Only on December 18 did their lack of ammunition compel them to stop fighting, but even then they did not surrender. Divided into two groups, they managed to infiltrate westward through German lines. The Germans were amazed at the determined American resistance in Weiler during the almost three-day fight.

Defending Wahlhausen to the last man

This village was defended on December 16 by the 1st Platoon of Company I, about 41 GIs commanded by a lieutenant named Fisher. From their outpost, they directed artillery fire from the 109th Field Artillery Battalion’s Battery C in Bockholtz onto the enemy troops approaching the village. The Germans’ original plan was not to tangle with the Americans here but instead storm forward to the Clervaux bridges; however, two German regiments became involved in fierce combat with the American platoon.

As the platoon beat off attack after attack, the ammunition began to run out. Although the Americans were supported from time to time by some counterattacks by their comrades in Weiler, the Germans moved to surround the village. About noon, the almost encircled 1st Platoon was barely holding out and urgently ordered a resupply of ammunition. This request was in vain because the American tank crews would not take the risk of advancing so far east.

Late in the afternoon of December 16, Wahlhausen was not only surrounded but also partially occupied by the Germans, with the 1st Platoon defenders caught in the middle. By 6:30 PM, Lieutenant Fisher contacted the Company I command post for the last time and ordered artillery fire on his own position. Forty GIs and more than 100 Germans fell to the disastrous fire, while only one GI survived and escaped.

Defending Marnach with a “defiance of death.”

The command post of the 110th’s 1st Battalion, along with Company B and five antitank guns, were in Marnach with Lt. Col. Donald Paul in command. At 5:30 am on the 16th, the Germans unleashed a huge barrage with artillery, antiaircraft guns, and mortars against the battalion. As the German infantry advanced on the village, many were caught in a minefield and killed. At 8 am, the Germans launched a major attack on Marnach with 12 companies, but they were met with stiff resistance by Paul’s defenders. Two hours later, Paul asked regiment for reinforcements. None were forthcoming.

In the afternoon, the situation got worse for Company B. The self-propelled and towed artillery at Heinerscheid had

broken down, and by 4 am the next morning, German engineers had finished with the construction of a 60-ton bridge over the Our River at Dasbourg that allowed panzers, assault guns, and heavy weapons to cross the river and advance toward the American positions. At nightfall, Lt. Col. Paul sent his last radio message: “German tanks are just going on to enter Marnach.”

The Germans advanced and attacked violently and incessantly with artillery and heavy tanks against the Company B infantrymen. Twice, a few German tanks entered Marnach and rolled to the local church, but they were repulsed on both occasions. Although the German superiority in men and matériel was overwhelming, the GIs could not be demoralized in spite of their precarious situation. Marnach was a very important and strategic place with roads leading in several directions.

In the area of Marnach and Munshausen, the 110th Regiment found itself fighting against five German armored regiments. Colonel Meinrad von Lauchert, commander of the 2nd Panzer Division, said after the war, “During the first attacks on Marnach, we found that all our preliminary fire on that village had no effect for our assault troops. The American soldiers there defended the village foolhardily and with a never-experienced defiance of death.”

Company C’s “wild warriors” in Munshausen

Munshausen is a small village less than two miles southeast of Clervaux and about four miles southwest of Marnach; it was one of the 110th Infantry’s vital strongpoints protecting Clervaux. Company C’s 1st Battalion had dug in around the village before the German attacks had begun, and their supporting artillery was emplaced west of the village.

On the morning of December 16, the defenders sent out a patrol through the forest to the east looking for the Germans’ approach. They did not have to look very long. When the enemy attack started on the village, the men of Company C defended it skillfully and had the situation well in hand from the beginning. During the entire day, the defenders of Company C fought like “wild warriors” and killed or wounded many Germans.

Six supporting M5 Stuart light tanks left Munshausen in the morning to help the Marnach garrison that was protecting the important Dasbourg-Clervaux Road. On the way to Marnach, five of the tanks were hit by German shells and immobilized. Only one tank was able to return to Munshausen.

On Sunday, December 17, a group of enemy soldiers appeared on the northern outskirts of Munshausen from the direction of Marnach. They were furious at the Americans because of the casualties they received as they tried to break through overturned trucks and a large wire barricade the defenders had erected. As the Germans cleared the barricade, they became perfect targets for American snipers. When the Germans did at last break through the perimeter of the village, the valiant defenders fired at them from every window, forcing the Germans to request support from the panzers fighting at Marnach.

Besides tanks, the Germans needed a new plan to conquer the village, so their artillery began bombarding it with phosphorous shells that set fire to the houses and barns in an effort to burn out the men of Company C. Unfazed, the GIs continued to fire their machine guns and rifles from windows and cellar doors at the German tanks and armored infantry accompanying them. During two full days of battle, every house in Munshausen had to be stormed by the Germans at a high cost in casualties.

Finally, at 4 am on Monday, December 18, the valiant American defenders had to be withdrawn because of the flood of German tanks pouring into the village. Although they could not stop the German advance, the GIs were able to tie up many German tanks and infantry for more than two days, seriously throwing off the German timetable for their counteroffensive.

Tough resistance in Hosingen

The early hours of December 16 were hell in Hosingen as German artillery shattered the village—located on Skyline Drive three miles east-southeast of Munshausen—with high-explosive and phosphorous rounds and flamethrowers. Five houses caught fire and seven deuce-and-a-half trucks belonging to Company H, 110th Infantry, and Company B, 103rd Engineers were destroyed. The Germans planned to soften up the defenders and destroy their spirit of combat all in one go, but the American garrison withstood and resisted with resolution.

One company of Maj. Gen. Heinz Kokott’s 26th Volksgrenadier Division advanced south of Hosingen in the direction of Bockholtz, while three companies arrived at the village. The American defenders fought off the first German assault on the village, with four Sherman tanks firing into the German infantry, creating deep gaps in their attack groups. The situation turned so bad for the Germans that they fell back, leaving 32 dead.

Not to be deterred, the German encirclement around Hosingen tightened and Wehrmacht troops tried to enter the village, coming from three directions with bicycles and artillery pulled by horses. Company K fired their mortars at the advancing enemy, delaying them for about two hours. At 10 am, the Germans lobbed mortar rounds into the village center and destroyed three more American trucks.

As the German infantry entered the village, the Americans withdrew to the western side of Hosingen, setting fire to many houses to prevent the Germans from occupying them. By 2 am on Monday, December 18, a German group with two machine guns was spotted approaching the command post of Company B, 103rd Engineers. They were eliminated by sub-machine guns and hand grenades.

The tough resistance of the Americans was so violent that at first the Germans had to bypass Hosingen to the north and south. They then assembled more than 20 tanks and armored cars around the village, taking aim at the houses. After destroying a few of the enemy’s tanks, the GIs realized they were completely surrounded and out of ammunition.

The situation was hopeless, so Captain Feiker of Company K, 110th Infantry and Captain Jarret of Company B, 103rd Engineers fashioned a white flag made of white toilet paper on a stick with which they approached the German line. With a heavy heart, the Americans surrendered to the Germans, but not before destroying much of their equipment and delaying them for two days.

2nd Panzer Division attack on Clervaux

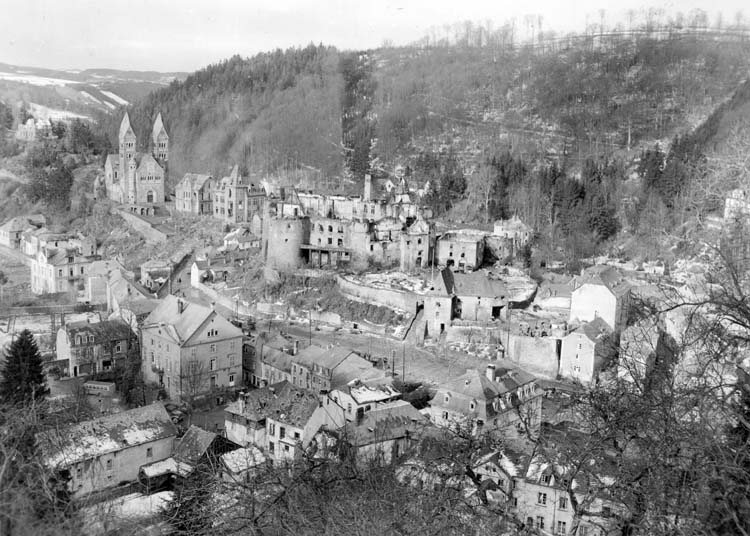

Once the important road center at Marnach had been lost to the Germans on December 17, the attack on the vital town of Clervaux began. Thirty German heavy tanks and half-tracks moved slowly down the steep and winding road from Marnach to the town set deep in a valley.

At the first hairpin bend, a few Sherman tanks from the 2nd Platoon of Company A, 707th Tank Battalion lay in wait. The American Shermans were no match for the German Mark V Panthers, and after a fierce duel, several destroyed U.S. tanks—as well as German ones—blocked the road. The Germans pushed them down the precipice, and their infantry finally reached the entrance to the town. It was tough going, though, for Colonel Lauchert and his 2nd Panzer Division. At noon, dogged street fighting started.

The commander of VIII Corps, Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton, had ordered a detachment of armor to Clervaux to support Colonel Hurley E. Fuller’s 110th Infantry in the defense of the town. Fuller’s command post was located in the Hotel Claravallis next to the important Clerve Bridge. The bridge was guarded by the regimental headquarters company, which had set up in the old castle nearby.

At the hotel, which was being shelled by artillery and Nebelwerfer rockets, Fuller tried to get a picture of what was happening at his forward outposts, but learned that all communications to his companies had been severed.

The Germans fought with a tremendous toughness and occupied the slope to the east of the town next to the Hotel du Parc. From there, they could bring fire on the defenders in the town and at the castle. A German report of the action stated, “Especially from an old fortress tower, the Americans fired with towering rage so that our infantrymen couldn’t advance without bad casualties. Only when we brought two AAA guns [88mm] into action did we manage to fight these GIs powerfully.”

On the afternoon of December 17, American armor, antitank guns, and snipers dominated the area around the Clerve Bridge. At this time, a German reconnaissance patrol tried to enter the town from the north without success. Finally, that evening, German tanks and mounted infantrymen fought their way across the Clerve Bridge and entered the town.

When tanks from Lauchert’s 2nd Panzer Division—regarded by the Americans as Germany’s best armored division—rolled up to Fuller’s command post and stuck their barrels into the windows before firing, he was forced to evacuate. Along with a small group of wounded survivors, Fuller left the crumbling hotel from a third-floor window at the rear of the building by way of a narrow iron footbridge (while holding a blinded soldier by the hand) in an attempt to escape over the rocks in the direction of Doennange, a few miles away. He and his group were taken prisoner the following day, but still, the resistance of the Americans did not end.

In the ruins of the 12th-century castle located high above the town, about 100 American officers and men continued to resist against the Germans who tried entering the castle yard but were greeted by a flurry of gunfire. About 100 civilians from Clervaux were taking shelter in the castle’s huge cellar at the same time. The town was teeming with Germans when, finally, the Americans’ situation in the cellar below the castle became critical.

As a last resort, the Germans bombed the castle with phosphorous rounds, trying to burn the defenders out, and they broke down the gates with panzers. At this point, the Yanks had no choice but to stop fighting. Most escaped, while some were killed and 80 were captured. At last, the Germans managed the conquest of Clervaux but, in the process, the 2nd German Panzer Division was almost three days behind schedule.

Cooks, clerks, and drivers defend Consthum

At about 6:15 am on Saturday, December 16, the German 26th Volksgrenadier Division approached the tiny hamlet of Holzthum, four miles south of Marnach. Even after several attacks on this day, the Germans could not conquer the village, as each attempt was repelled by the men of Company L, 3rd Battalion.

That night, the Germans decided to bypass the strongly defended village and advanced in the direction of Consthum, a little over a mile to the southwest of Holzthum. The Company L men delayed the German advance and gave their comrades in Consthum time to prepare a defense. Based on Company L’s actions in Holzthum, Company M in Consthum had enough time to organize cooks, clerks, and drivers into a defense against the Germans. The men could not believe it when the Germans stopped short of their positions. They were able to inflict tremendous damage on the 26th Volksgrenadier and Panzer Lehr Divisions before they moved on to the important transportation hub of Wiltz, where the 28th Division had its headquarters.

Camille P. Kohn, the president of CEBA, wrote this about the 110th’s action: “I do not know any other regiment that has accomplished such a performance in Luxembourg than the 110th Infantry! This outstanding unit deserves really an appropriate mark of distinction, if only for those indescribable achievements in Luxembourg during the dark days of 1944. In their combat zone, they contributed in a very rare manner to prevent the Hitler aggressors to conquer Bastogne, and last but not least, reach the final objective: the harbor of Antwerp.”

That the 28th Division’s scattered and battered units could hold out against such odds, delaying the Germans as long as they did, was by any standard an incredible feat. The 110th Regiment alone fought elements of three German divisions; the 28th Division would identify nine German divisions in their sector before the fighting was over.

The German pressure continued to build increasingly in the form of tanks and armored vehicles carrying more German infantry. Nonetheless, the 110th, hunkered down with nowhere to go right in the middle of the Germans’ chosen route through Luxembourg, hung on. Small, determined units, running low on ammunition, food, water, medical supplies, and antitank weapons, continued to stand and fight until they were forced to retreat, were killed, or were captured.

The toll on the Germans was so costly in men, equipment, and time that Hitler’s race for Bastogne was lost right where it began among the widely scattered outposts of the 110th Regimental Combat Team. The 110th Infantry’s self-sacrifice gained crucial time that allowed the arriving 101st Airborne Division to move into positions to the rear of the exhausted 28th Division around Bastogne.

When all the smoke from Bastogne had cleared and the cleaning up of the battlefield was done, the 101st Airborne Division and its attached units had halted the German push to Antwerp and the 110th Regimental Combat Team, 28th Infantry Division was left with few survivors, yet it had done its job when the chips were down, and had done much to help the Americans achieve victory in the Battle of the Bulge.