By Ludwig H. Dyck

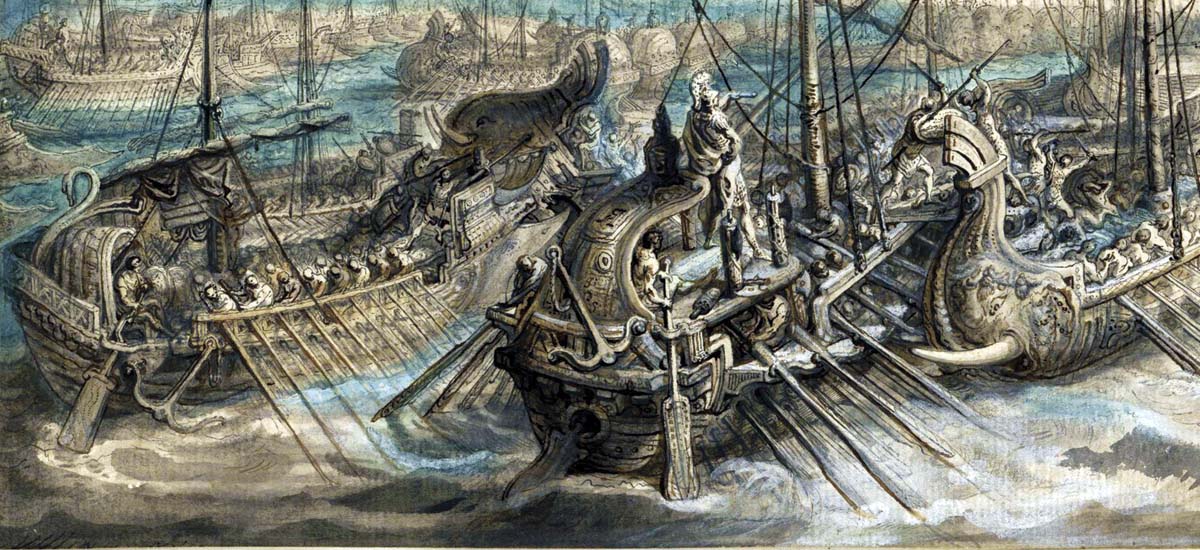

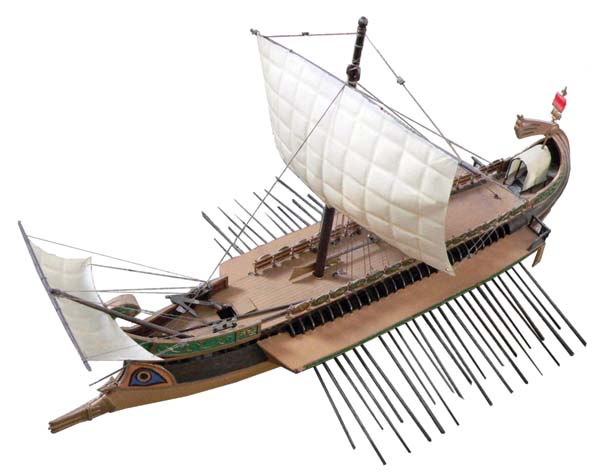

The huge gangplank dangled in the air, suspended by a rope and pulley from a massive pole standing upright in the bow of the Roman galley. From the top of the gangplank a spike protruded like the beak of a gigantic bird. Indeed, later the devices later became known as the corvus (raven). The Carthaginian crews on the opposing ship had never seen anything like it. Down the gangplank dropped, thundering onto the Carthaginian ship where the spike embedded itself into the deck. Over the gangplank came the Roman marines with their shields up and blades drawn. The Carthaginian crews were flabbergasted. They were used to fighting sea battles by ramming; but now they had to fight, hand to hand, against some of the best soldiers of the ancient world. It was 260 BC, the fifth year of the First Punic War, the greatest naval conflict of the ancient world. (Read more about the ancient battles that shaped the modern world inside Military Heritage magazine.)

The emerging empires of Rome and Carthage were kept apart for a long time by different spheres of interest. Traditionally founded in 753 BC, Rome was busy extending her sway over Italy, defeating native hill tribes and invading Gauls, overcoming the ancient Etruscan civilization and absorbing Greek coastal colonies. Rome became a formidable land power in contrast to Carthage, which ruled the sea.

Carthage began as a Phoenician colony founded in 814 BC, on the coast of northwest Africa. Carthage’s mother city of Tyre fell first to the Babylonians in 585 BC, then to the Persians, and finally to Alexander the Great in 332 BC. The Phoenician elites fled Tyre for Carthage, from where they built a new empire. Native Libyans were exploited to toil in the fields, to fight in Carthage’s armies, and to man her ships. The Phoenician culture dominated, and Phoenician remained the language of the ruling class. At the same time, though, the Phoenicians intermarried with the Libyans. In time a new culture, that of the Liby-Phoenicians, was born. The great wealth of Carthage’s trading empire bought mercenaries and won her tribal alliances. Carthage blossomed into the largest and richest city of the western Mediterranean. From the Latin punicus (Phoenician), the Carthaginian Empire became known as the Punic empire. Its conquests extended to southern Spain, Sardinia, Corsica, and western Sicily.

The Politics that Drew Mortal Enemies into the First Punic War

Although fated to be deadly enemies, Rome and Carthage shared similar political structures. Both were former monarchies that had become republics, ruled by two annually elected magistrates—the Roman consuls and the Punic Shofets (suffetes in Latin)—alongside a senate and council of elders, respectively. Disagreements between these two governing bodies were referred to an assembly of the people. Senior political posts combined both civil and religious functions; however, unlike the consuls, the suffetes did not lead armies in war. In both Rome and Carthage, wealthy oligarchies monopolized the leadership. Relations between Rome and Carthage remained relatively peaceful until a crisis developed over Sicily.

In those days, Sicily’s rugged hills were still largely covered in forests, rising to their highest peak at the 10,900-foot volcano of Mt. Etna. Sicily was “the noblest of all islands,” wrote Diodorus Siculus, and for that reason both powers desired to control it. Since prehistoric times, diverse peoples had settled on Sicily’s fertile lands. Among them were the Siculi, from whom the name of Sicily was derived. Starting in the 8th century, Greeks and Phoenicians arrived to set up colonies. They spread their influence over the natives and used them in their own rivalries and wars for possession of the island. From 304-289, the most powerful of these colonies, Greek Syracuse, was ruled by the tyrant Agathocles. In his employment were Campanian mercenaries known as the Mamertines (after Mamer, another name for Mars), who would draw Rome into Sicilian politics and into the First Punic War.

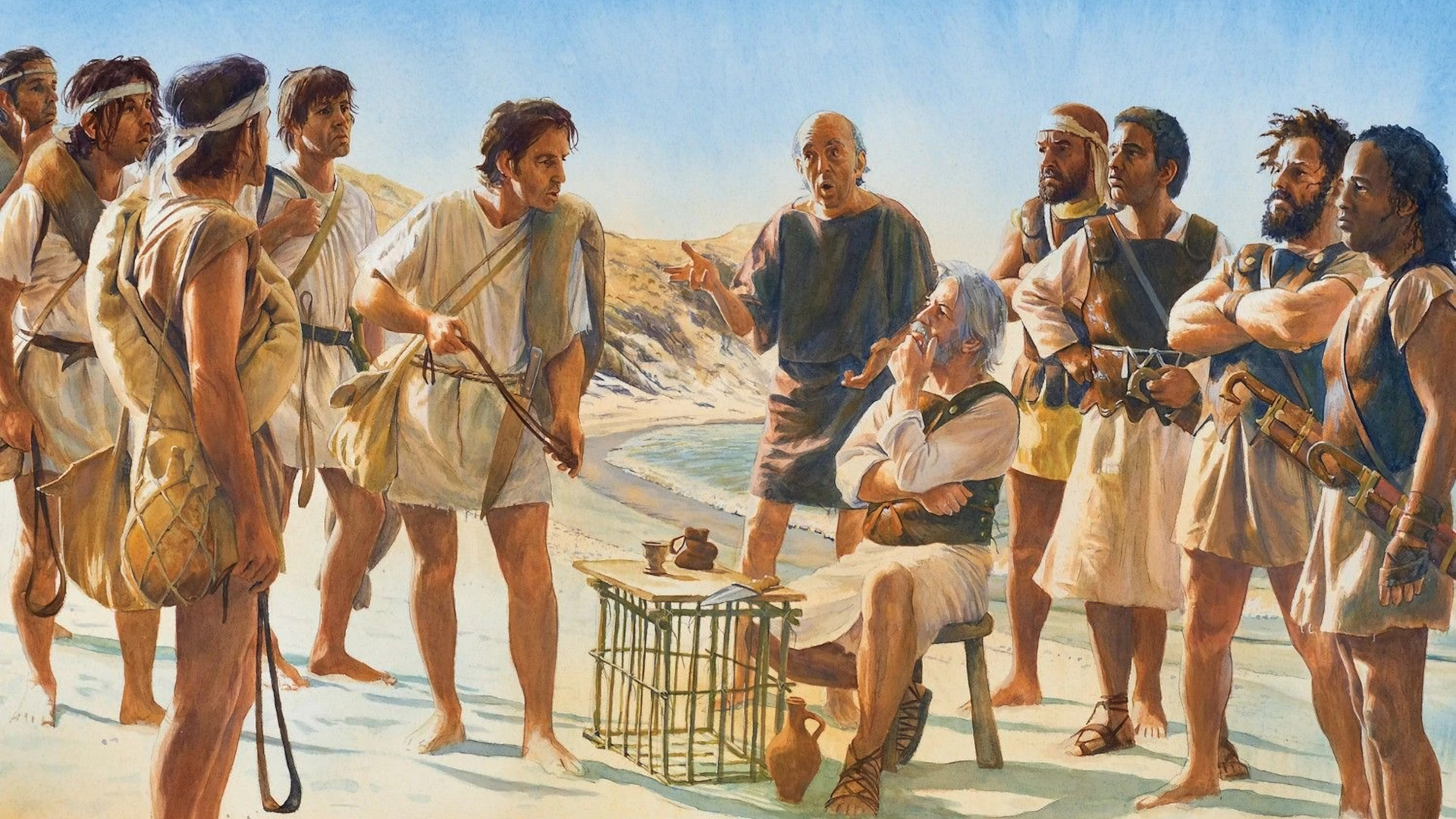

In 288 BC, a year after Agathocles’ death, the unemployed Mamertines faked friendship to enter the beautiful city of Messana (Messina). Once inside they enslaved, raped, and slaughtered the inhabitants. From Messana, the Mamertines raided northeastern Sicily and harassed their erstwhile employer Syracuse. Although they were defeated by Pyrrhus, King of Epirus (reigning from 306-302 and 297-272), who had come to help Syracuse against Carthaginian expansion, the Mamertines retained their hold on Messana. Concentrating on the greater enemy, Pyrrhus reduced the Carthaginian presence in Sicily to the sole stronghold of Lilybaeum (Marsala) on the western coast. Yet Syracuse lacked the spirit to finish off her old enemy and no longer desired Pyrrhus’ service. Pyrrhus returned to Italy, where he had been warring with Rome. The Mamertines resumed their raiding, wreaking havoc for nearly a decade until somewhere between 269 and 265, when they were twice defeated by Syracuse’s general and consequent king, Hiero. The Mamertines asked Carthage, which had rebuilt much of its power in Sicily, for help. They also asked Rome.

The Mamertines reminded Rome that they were kinsmen from Italy, but Rome was loath to help. The Mamertines’ massacre at Messana had inspired a Roman garrison at allied Rhegium (Reggio Calabria) to likewise turn on the hapless population. Rome had executed its turncoat garrison; now Rome was suppose to help the equally wretched Mamertines?

The problem lay in Carthage’s involvement. Rome’s interests increasingly expanded beyond Italy’s shores. Rome, the land power, ultimately clashed with maritime power Carthage, as might be expected, over an island. If Carthage were to gain hold of Messana, her fleet and armies would be on the doorstep of Italy. For a long time the Romans debated. The Senate staunchly disapproved but were overruled by the assembly of the people and the consuls, who promised everyone great plunder. Consul Appius Claudius Caudex was appointed to lead the expedition in 264. It was the first time a Roman army would leave Italy by sea. And while Rome deliberated, Carthage installed a garrison at Messana.

Having decided to throw their lot in with Rome, the Mamertines evicted the Punic garrison. Rome’s involvement drastically upset the Sicily’s power dynamics. For both Carthage and Syracuse it meant that Rome was now their greatest contender for Sicilian dominance. To counter the Punic loss of Messana, Carthage’s commander, Hanno the Elder, won over not only Acragas (Agrigento), another Greek colony, but also Syracuse. Former enemies, Hanno and Hiero set up separate camps to blockade Messana by land and sea.

Rome relied on ships—triremes and quinqueremes—from allied Tarentum, Lorcri, Velia, and Naples to carry her troops. The standard warship since the latter half of the six century, the long and sleek trireme galley featured three banks of oars with a rower on each oar. In the naval arms race that followed, larger ships were built. The relationship between the design of the ships and their names is poorly understood. It seems that rather than adding more banks of oars, the number of rowers per oar was increased, so that on a quinquereme there were two men on the oars of the upper and middle banks and one on the lower. The bulk of the rowers probably hailed from Rome’s proletarii, the poorest citizens, alongside liberi freemen. Given Rome’s initial inexperience in naval warfare, a large number of the captains and skilled deck crews were provided by allied Italian coastal cities.

Undertaking a risky night crossing to slip through the Punic naval blockade, Consul Claudius brought his Roman army to Messana. All did not go smoothly, though, as there were some limited attacks by Punic ships. One of them ran aground and was captured by the Romans. At Messana, Claudius was impressed by the enemy forces arrayed against the city. He tried to parley, but when that approach failed, he launched an offensive. Rome’s legions and allies proved more than a match for their adversaries, who were routed and driven off the field one after the other. As to the Mamertines, they were no longer mentioned, their fate eclipsed by the larger conflict between Rome and Carthage.

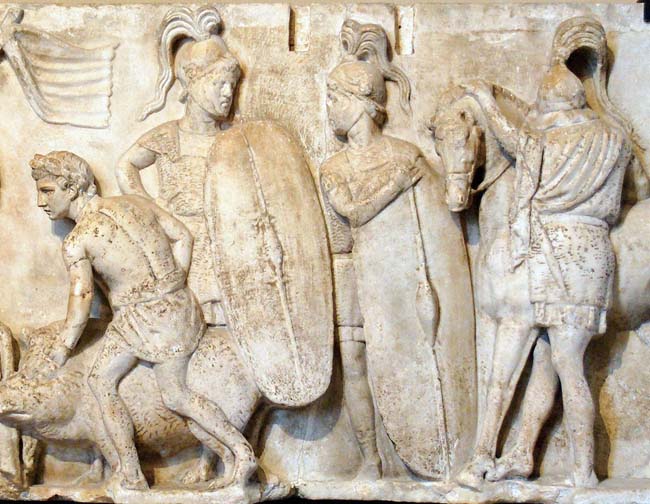

When the Romans first agreed to help the Mamertines against Hiero, they did not envision themselves drawn into a war with Carthage, but now they were emboldened by Claudius’ victory. In 263 BC, the consuls Manius Otacilius Crassus and Manius Valerius Maximus arrived in Sicily with their two consular armies. Together, the two armies totalled 40,000 soldiers, including four legions of 4,000 legionaries and 300 cavalry each, as well as four alae (formations of conscripts) of Italian allies. Although well trained, the legionaries were not professional soldiers, but rather a levy of citizens, recruited mostly from the rural population. Few could have guessed how long the First Punic War would last. Kept in service for years, the recruits would become hardened veterans.

The size of the Roman forces and their capture of Hadranum (Adrano), at the base of Mt. Etna, intimidated scores of Sicilian settlements into surrender. Most notable among these was the city of Syracuse itself. Hiero agreed to pay 100 talents of silver and to limit Syracuse’s domains to southeast Sicily and north along the coast to Tauromenium (Taormina). More importantly, Hiero would secure the Roman supply chain to the mainland. Henceforth, Hiero ruled wisely and remained loyal to Rome. He protected Syracuse with a strong fleet and employed his famous kinsman, Archimedes the Greek, who invented ingenious mechanical defenses for the city.

The Acragas Siege

In summer 262, the consular armies of Lucius Postumius Megellus and Quintus Mamilius Vitulus blockaded the city of Acragas. The city lay on a plateau several miles from the sea. Hannibal, son of Gisco and father of Hanno, led the defense of the city. When a number of Romans foraged for grain outside the city, they were set upon by Carthaginian soldiers who sortied out of the gate. Scattering the foragers, the Carthaginians continued on to assault the Roman camp. The legionaries put up a bitter defense until their slain Carthaginian foes lay piled in heaps beneath the stockade. Now it was the Romans’ turn to sortie out, cutting down the fleeing Carthaginians, of whom only a few escaped back to Acragas.

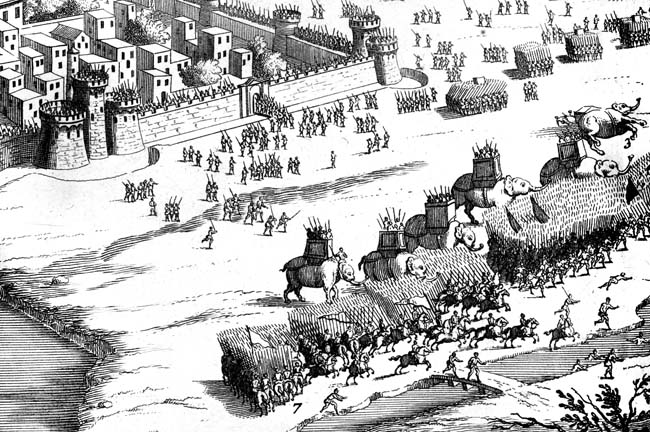

The siege had lasted for five months when reinforcements from Carthage arrived at Lilybaeum. Hanno, who was in command of the relief column, had 50,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 60 war elephants. In all likelihood, the pachyderms were recently introduced into the Punic army. Hanno marched his army to Heraclea and, aided by treachery, looted the main Roman supply depot at Herbessus.

Though Hiero of Syracuse continued to provide a lifeline, food shortages soon made themselves felt in the Roman camp. In their weakened state, the soldiers were more vulnerable to pestilence, which further depleted their ranks.

After winning a cavalry engagement, Hanno set up camp on a hill close to Acragas and waited. When famine and pestilence also beset Acragas, Hanno engaged the Romans in a decisive battle for the city. The fighting was long and hard, but at last, the Romans overcame the Ligurians and Celts who bore the brunt of the enemy’s fighting. When the elephants and the rest of the Carthaginian ranks came under direct Roman attack, the Punic army broke into confusion.

Elated by their victory and exhausted from battle, the Romans neglected their sentries. Hannibal and his mercenaries slipped out of Acragas at night and crossed over the Roman trenches by filling them with baskets full of chaff. At daylight, the Romans were skirmishing with the rear of Hannibal’s column, but their primary focus remained Acragas.

Rome had suffered 30,000 casualties in the siege and battle. When the city fell, the Romans were eager for their grim rewards of rape and plunder. They enslaved more than half of Acragas’ population, which amounted to approximately 25,000 people. It was a clear signal to the Sicilian city-states that still sided with the enemy. The disgraced Hanno had to pay a fine of 6,000 gold pieces and was replaced by Hamilcar as Carthage’s main commander in Sicily.

Although the Romans rejoiced at the fall of Acragas, it was obvious that victory over Carthage would only be possible if the Punic navy were defeated. Rome had to become a naval power, a strategy as audacious as it was challenging.

Rome Tries to Become a Naval Powerhouse

Knowing comparatively little of building and sailing ships, Rome used the Punic ship captured during Claudius’ crossing as model of her own war galleys. In training, Roman marines rowed their oars while sitting on benches, arranged as they would be on a ship, while sitting on dry land. In this way, the crews were trained even before the ships were built.

Roman naval operations nevertheless started with a fiasco. In 260 BC, Consul Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio was lured into the harbour of Lipara, the main city on the Aeolian islands, by the false news that the city was ready to switch to the Roman side. Scipio ended up being captured by the Punic fleet, alongside 17 Roman ships.

Command of the Roman fleet fell to Scipio’s co-consul Gaius Dulius. Dulius sailed towards Mylae (Milazzo), where Hannibal Gisco, who had assumed command of the Punic fleet, could not wait to engage the Romans. Hannibal stood proudly on the prow of his flagship, a mighty septireme that had belonged to King Pyrrhus. Hannibal believed that his ships were like “predators after easy prey,” according to Polybius. The two fleets were fairly even in size, with the 130 Punic ships slightly outnumbered by 145 Roman ones.

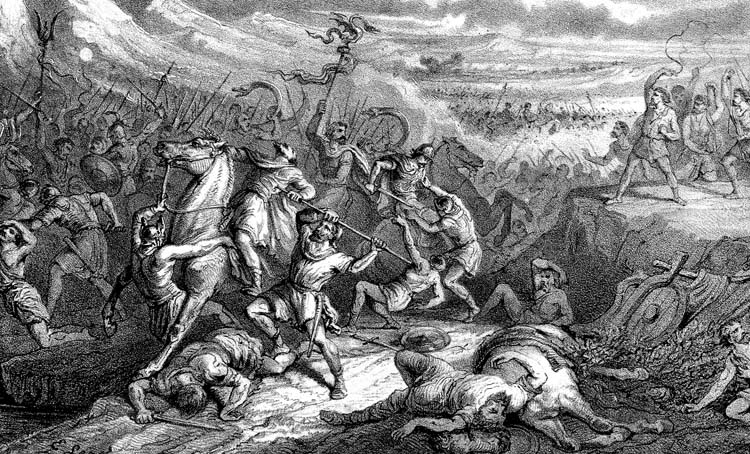

As the fleets approached one another, the Carthaginian crews espied the strange poles and drawn-up gangplanks on the bows of the Roman ships. With its beak-like spike, the corvus pinned the Roman ship to the Punic one. Two abreast, the Roman marines advanced over the 36-foot long gangplanks, deflecting Punic javelins with their oval shields. Swarming the decks of the Punic ships, the marines cut down the Liby-Phoenicians and the mercenaries who fought alongside them. The Carthaginians lost 50 ships before they retreated. Among the captured ships was the flagship of Hannibal, who somehow “escaped by the skin of his teeth,” wrote Polybius.

After their upset of Punic naval dominance at Mylae, the Romans retained the initiative on land and sea. From 260 to 257 BC, the Romans relieved Segesta, captured a string of towns, and besieged Lipara. The only notable Punic land victory occurred when Hamilcar ambushed 4,000 Roman allies as they were breaking camp. At sea, Rome defeated and trapped Hannibal Gisco’s fleet in a Sardinian harbour. Blaming Gisco for their predicament, his men arrested and crucified him for the defeat. The Roman fleet then fought another engagement off the coast of Tyndaris (Tindari). The Carthaginians destroyed Consul Gaius Atilius Regulus’ vanguard. They nearly captured the consul before the rest of the Roman ships arrived and chased them away. Rome also extended the war to the shores of Sardinia, Corsica, and Malta.

One of the Largest Seat Battles in Antiquity

The year 256 saw an unprecedented build up for a titanic naval battle. The Romans launched a new fleet of 330 ships; the Carthaginians sailed forth with 350 ships. The Romans intended to bring the war to the Punic homeland. To do so, they had to destroy the Punic fleet. On board the ships of the Roman fleet was an expeditionary force of the best troops from her land army, serving as marines. Each ship held 120 marines as well as 300 oarsmen, for a total of 138,600 men. The Punic fleet was anchored at Heraclea, Minoa, and aware of the Roman intentions. Manning the Punic ships were 150,000 men, who were told by their commanders that everything depended on victory at sea. If the enemy set foot on Libyan soil, then surely they would subjugate the whole country.

When the Punic fleet intercepted the Roman fleet off Cape Ecnomus, the ensuing conflict was possibly the largest sea battle in antiquity in terms of men involved.

Leading the Roman fleet were the two “sixers,” or hexaremes, of consuls Marcus Atilius Regulus and Lucius Manlius Vulso. The Roman ships attacked in triangular formation, the base of which towed the horse transports. Another protective line of ships brought up the rear.

The Punic ships bore upon the Romans in a broad but thin linear formation. The longer right wing stretched far into the ocean and was commanded by Hanno the Elder, who had returned to service in 258. The shorter left wing, commanded by Hamilcar, was deployed at an angle to the coastline.

The Roman wedge intended to smash its way through, something Hamilcar had anticipated. The Punic ships facing the apex of the Roman triangle retreated, luring the Roman ships after them. With the Roman center ruptured, the Punic wings rowed inward to attack the base of the Roman triangle, which was slowed by the horse transports. Seeing the danger, Regulus and Vulso turned their ships about and rowed to the relief of their hard-pressed comrades to the rear. A furious battle ensued, with the Punic ships attempting to ram but risking being pinned by a corvus. At one point, the battle dissolved into three separate engagements before ultimately ending in a Roman victory.

The Romans lost 24 ships. Punic losses amounted to 30 ships sunk and 64 captured.

Too Many Mouths to Feed

Following through with their invasion plans, the Romans beached their ships south of Cape Hermaea (Cape Bon) and seized town of Aspis (Kelibia). While the main Punic forces remained holed up in protection around Carthage, Roman soldiers ransacked countryside villas, farms and settlements. Twenty-thousand people were dragged into slavery, alongside herds of livestock. Vulso transported the loot and the enslaved population back to Rome. Regulus stayed behind with 40 ships, 15,000 infantry, and 500 cavalry.

Bringing reinforcements, Hamilcar arrived from Sicily to join the Punic army at Carthage. He shared command with Bostar and Hasdrubal, the son of Hanno. The Punic army arrived on a ridge above Adys (possibly Uthina), which Regulus was besieging. It was Regulus, however, who struck first; his warriors set off at night, hiked uphill, and attacked the Punic relief army at dawn. The rough ground on the ridge was ill-suited for the cavalry and elephants, negating the Carthaginians’ greatest advantage. Nevertheless, the mercenaries forced back the legions but then were outflanked. Breaking in panic, the fleeing mercenaries caused the entire Punic army to collapse. Regulus was left free to loot scores of settlements, including Tunis, which was situated just 13 miles from Carthage.

Raids into Punic territory were undertaken not only by the Romans, but also by Numidians from neighboring kingdoms. Incensed by earlier Carthaginian incursions, the Numidians exacted their revenge. Refugees fled to Carthage where, in Polybius’ words, there were “too many mouths to feed.” Teetering on collapse, Carthage sent envoys, but the surrender terms Regulus demanded were “no better than slavery,” wrote Diodorus. Carthage would fight on.

In an effort to appease the gods, the Carthaginians revived long-neglected ancient sacrifices. Possibly among these was the most dreadful of Phoenician rituals, no longer practised in Tyre but now carried out in Carthage: the sacrificial burning of infants to the god Ba’al Hammon and his consort Tanit.

Salvation arrived in 255 with the Spartan mercenary Xanthippus. The veteran soldier re-drilled the Punic army until the men cheered him and could not wait to fight the Romans.

The opposing armies bivouacked close to each other near Tunis. Punic forces numbered 12,000 infantry, 4000 cavalry and nearly 100 elephants. The forces were evenly matched, with the Romans enjoying a superiority in infantry but being weak in cavalry. While the Punic commanders debated about how to proceed, the soldiers formed their own battle lines and called for Xanthippus to lead them. Xanthippus urged an attack while the men’s spirits were so high.

The elephants formed a single central line at the front. Behind them, a second, broader line was made up of Carthaginian citizen infantry in close-order formation on the left and mercenaries on the right. Libyan and Numidian cavalry and light infantry were deployed on the flanks. The Libyans typically fielded shock cavalry, armed with thrusting spears. The Numidian cavalry preferred skirmishing tactics, riding bareback without bridle, armed with javelins and small round shields. The elephants swatted their ears and dangled their trunks, the horses snorted and pawed the ground. The men likely stood apprehensively ready or boasted of their courage.

The Romans positioned their light troops in front, followed by a deep center of legionary maniples (formations of 120 men). Although confident that the mercenaries would cause them no trouble, the Romans were wary of the elephants. The prospect for the Roman cavalry looked dim, as well. Deployed on the wings, they faced their Punic counterparts, which outnumbered them several times over.

The drivers goaded their elephants forward, while on both Punic wings the cavalry bolted forth. The Roman ranks resounded with the clattered of spears against shields, as with a great shout they, too, advanced into battle. The Numidian and Libyan cavalry horsemen routed their overwhelmed Roman counterparts after a brief fight. Against the mercenaries, however, the legionaries proved triumphant, driving them off the field. But the day belonged to the elephants, which scattered the Roman light troops and plowed through the ranks of legionaries. For a while, the depth of the Roman lines slowed the great pachyderms. Then, though, the Punic cavalry returned, flinging volleys of javelins upon the Roman flank and rear ranks. A number of Roman soldiers evaded the elephants, only to be decimated by the long spears of the citizen phalanx. Hemmed in by the cavalry and crushed by the elephants, nearly the whole Roman army was annihilated.

280 of 364 Warships Lost

The 2,000 legionaries who had chased after the mercenaries were the only ones who made it back to Aspis. The Punic losses only numbered 800. Regulus initially escaped the massacre, but ended up being taken prisoner. The Carthaginians purportedly cut off Regulus’ eyelids, so that he could not shut his eyes while he was trampled to death by an elephant. Carthage rejoiced in its victory and sacrificed to its gods.

Early in summer 255, the fleet of consuls Marcus Aemilius Paullus and Servius Fulvius P. Nobilior decisively defeated a smaller Punic fleet near Cape Hermaea. After picking up the Roman garrison of Aspis, the Roman fleet sailed back towards Sicily in July. Along Sicily’s southern coast the Roman fleet got caught in a violent storm. Ships capsized and sank while others were smashed by waves against submerged rocks and headlands. The beaches from Camarina to Cape Pachynus were littered with wrecks, flotsam and jetsam, and corpses of men and horses. Of the 364 warships, 280 were lost. Three hundred cavalry transports and various other vessels were lost as well. Polybius called it the greatest disaster at sea ever.

Encouraged by Rome’s misfortune, Punic commander Carthalo retook Acragas and razed it to the ground. In 254, Hasdrubal arrived at Lilybaeum with a new Punic army, including 140 elephants. Both sides had rebuilt their fleets: 200 ships for Carthage and 220, built in only three months, for Rome. Commanding the new Roman fleet were second-time consuls Caiatinus and Scipio. The latter had been released from Punic captivity some time after his capture in 260, presumably ransomed.

Taking on more ships at Messana, the consuls proceeded to seize Cephaloedium (Cefalu) through treason. Caiatinus and Scipio then laid siege to Drepana (Trapani) but withdrew when Carthalo arrived with a relief army. Sailing back east, the consuls decided to take Panormus instead. Woods grew nearly up to the gates, providing timber for the legionaries, who erected a palisade and dug a trench to enclose the city. The Romans had begun the war relatively unskilled in siege warfare, but they had learned. Siege engines destroyed a seaside tower, enabling the soldiers to battle their way into the outer city, or new town. Wreaking havoc, the Roman soldiers terrified the remaining population who were holed up in the inner old town. After negotiating surrender terms, the Romans allowed 14,000 people to buy their freedom, but they enslaved 13,000 others. Panormus’ grim fate induced Iaetia and Tyndaris to join the Roman side.

From 253 to 251, the Romans sluggishly continued the land war. The legionaries remained fearful of the elephants and stuck to the high ground. A major assault on the Punic position on Heircte (possibly Mt. Pellegrino) near Panormus met with no success, but both Lipara and Therma (Termini Imerese) were captured. At sea, the Roman fleet raided the Libyan shores, but then ran aground at Meninx (Djerba), the Island of the Lotus-eaters. Throwing heavy equipment overboard to lighten their loads, the Roman ships broke free when the tide returned. As fortune would have it, the fleet was caught in another disastrous storm off Cape Palinurus, which destroyed 150 warships.

In June 250, Hasdrubal devastated the croplands surrounding Panormus. Caecilius Metellus, the previous year’s consul, kept his two legions behind the city walls. Hasdrubal crossed over the river that ran in front of the city and set up camp, but neglected to fortify his position. The Celtic mercenaries were already getting drunk when the Carthaginian camp came under attack by Roman skirmishers. The elephant drivers mounted their elephants and easily drove off the Roman light troops. Pursuing the latter back to the walls, the elephants came under heavy fire from archers on the ramparts and from more light troops in the moat. Pin-cushioned with arrows and javelins, the elephants ran amok, flinging their drivers to the ground as they stampeded back to their lines. In their frenzy, they crushed any Punic soldiers who stood in their way. Seeing the enemy lines thrown into disorder, Caecilius’ legionaries charged from the city gate and routed the Punic army. The surviving elephants were captured and later displayed at Caecilius’ triumph in Rome.

Following Caecilius’ victory at Panormus, consuls Regulus and Vulso laid siege to Lilybaeum. Other than Drepana, Lilybaeum was the last Punic bastion on Sicily. Its garrison of 10,000 mercenaries was under the command of Himilco. The city’s walls were strong, a deep moat protected its landward side, and treacherous shallows filled the seaward approach. Battering rams were brought up, chipping away at the ramparts and towers closest to the sea. Undaunted, Himilco repaired old walls, built new fortifications and carried out limited sorties.

The Rhodian

To come to the rescue of Lilybaeum, Hannibal, son of Hamilcar, set off from Carthage with 50 ships and 10,000 soldiers. With too little wind to fill the sails, Hannibal anchored among the Aegates Islands (the Aegadians), northwest of Lilybaeum. When a strong breeze blew up, Hannibal sailed for Lilybaeum and slipped through the Roman blockade. Greeted by a cheering crowd, Hannibal dropped anchor within the safety of the harbour.

The reinforced Punic army sallied forth at dawn and launched a major assault on the Roman siege works. Himilco spearheaded the attack, but was met by mounting Roman opposition. The intensity of the fighting increased even as the corpses piled up. Heedless of their safety, thousands of Punic soldiers tossed flaming brands at the siege engines. Both sides were on the brink of collapse when the Punic trumpets sounded the retreat.

At night Hannibal’s fleet sneaked out of the harbour, making for Drepana. Some time afterwards, a lone ship likewise eluded the Roman galleys due to favorable winds and its unexpected direction from the nearby islands. The captain was another Hannibal known as the “Rhodian” (the Rhodians being famed for their skill at sea), who carried information between Carthage and Rome. The Rhodian’s advantage lay in his intimate knowledge of the shallows, his well-conditioned rowers and his superb ship. He even mocked the Roman ships, spreading the oars as if challenging them to pursue. Nor was the Rhodian the only blockade runner.

The Romans tried to fill in the harbour, but it was too deep, and the strong waves and current swept away the rubble they dumped to the bottom. With gigantic effort, the Romans piled up a sandbar, upon which a Punic quadrireme ran aground. Captured and taken over by a Roman crew, the quadrireme enabled them to catch the Rhodian’s ship and to prevent others from entering or leaving Lilybaeum’s harbour.

New Recruits for the Roman Navy

The assault on Lilybaeum continued until a great storm blew up, battering the Roman siege works, ripping apart sheds and toppling over towers. Advised by his Greek mercenaries, Himilco launched another sortie. Many of the siege works were old and of bone-dry wood. Stoked by the wind, they were easily set alight. The smoke, sparks and cinders blew into the faces of the Romans trying to combat the attackers and to extinguish the fires. Choking, coughing, and blinded, many Romans died before they even reached the fighting. In contrast to the Romans, the assaulting mercenaries had clear sight and air as they continued to feed the inferno. When the flames died down, all that remained were the charred bases of towers and burned beams of battering rams. The Romans were forced to give up their attacks on Lilybaeum; instead, they would starve the population into surrender or death by siege.

So many Roman marines died in the battles for Lilybaeum that not enough remained to man the oars of the navy. In 249, 10,000 new recruits arrived from Rome with Consul Publius Claudius Pulcher. Pulcher used the extra men in a naval offensive against Drepana. Arriving within sight of the walls at dawn, Claudius released the sacred chickens to consult the gods. In what was an ill omen, the chickens refused to eat. Claudius made things worse by disrespectfully throwing the chickens into the water “so that, as they would not eat, they might drink,” according to Cicero.

The Punic fleet sailed out of the harbour on the seaward side. At the same time, the Roman ships were already entering the harbour on the landward side. Claudius ordered the ships already inside the harbour to sail back out, causing a number of collisions. Oars snapped and marines cursed. Outside of the harbour, the Roman fleet reformed with their sterns to the shore and their bows toward the enemy and the open sea.

The battle signals were hoisted high, the oars plied the water, and the two fleets engaged. Gradually the Punic ships and seamanship began to win out, aided by the fact that the ocean was behind them. When in trouble, the lighter Punic vessels could disengage, withdraw to open water, turn around and re-engage. The heavier and clumsier Roman ships were rammed from the broad side or from behind. Trying to turn around or to escape, the inexperienced Roman crews got stuck in the shallows or beached their ships on the shore. Claudius and 30 or so ships managed to escape, but 93 ships, many with their crews, were captured by the Carthaginians.

Meanwhile, Co-consul Lucius Junius Pullus, who was elected for the year 249, arrived at Messana with a convoy of supply ships for the besiegers at Lilybaeum. Junius sailed for Syracuse with 120 war galleys and nearly 800 transport vessels. At Syracuse, he waited for the arrival of more ships from Messana and for grain from Sicilian allies. Junius send some of the warships and half the transports ahead with the quaestors. The latter were Rome’s financial officials, who could act as a second-in-command to the consul.

On the Punic side, Adherbal planned a raid on the Roman fleet moored off Lilybaeum. He entrusted the mission to Carthalo, who had arrived at Drepana from Carthage with 70 ships. Reinforced by Adherbal with another 30 ships, Carthalo attacked the moored Roman fleet at Lilybaeum at dawn. The Romans rushed forth to stop their ships from being towed away or burned, their stiffening resistance causing Carthalo to break off the attack.

Carthalo then sailed southeast along the coast until he happened upon the quaestors’ ships coming from Syracuse. The quaestors’ fleet, which consisted mostly of transports, eluded Carthalo’s galleys by taking refuge in the Bay of Gela. Behind spits of land, an allied sea-side town provided shelter. Setting up catapults and ballistae along the shore, the Romans drove off Carthalo’s fleet.

From the mouth of a nearby river, Carthalo’s fleet waited for the Romans to leave the safety of the bay. Instead, Carthalo’s lookouts spotted Consul Junius’ fleet making its way from Syracuse. Once more, the outmatched Roman fleet eluded Carthalo, finding refuge along a rugged stretch of coast. The weather now took a turn for the worse. Carthalo barely made it to the calmer waters around Cape Pachynus. Behind him, the storm accomplished what the Punic fleet had failed to do: Both Roman fleets were smashed against the rocks. The destruction was so completed that “even the timbers from the wrecks were useless,” wrote Polybius. Junius was fortunate to survive. To somewhat make up for the disaster, he captured the town of Eryx (Erice) on the ridge north of Drepana and the sanctuary of Aphrodite on the summit above.

For many years, the sieges of Drepana and Lilybaeum dragged on. In 247, Carthage made another Hamilcar commander of their navy. From his easily defended camp on Mt. Heircte, Hamilcar carried out coastal raids and guerrilla attacks. He struck like “baraq” (Punic for lightning), from whence he got his cognomen of Barca. In 243, Hamilcar Barca sailed towards Drepana, re-capturing the town of Eryx on the massif to the north. Setting up camp on the ridge, Hamilcar harassed the besiegers of Drepana.

With seemingly no end in sight for the sieges of Lilybaeum and Drepana, Rome decided for a third time to hinge its fate on the sea. Financed by loans from the richest Romans, a fleet of 200 quinqueremes was built. The new ships were based on the vessel from the Rhodian and no longer including the corvus. Early in the summer of 242, the fleet under Consul Gaius Lutatius Catulus reinforced the siege around Drepana.

Lutatius continued to drill his marines, preparing for the arrival of the enemy fleet. Punic response was long in coming, though, possibly because Carthage was running out of skilled seamen. It was not until spring 241 that a Punic fleet appeared under another Hanno. On board were grain and other supplies for Drepana and Lilybaeum.

Hanno anchored at the Sacred Isle (Marettimo), intend on crossing unseen to Eyrx. There, he would offload supplies and take on Hamilcar’s men to fight in the coming sea battle. Guessing Hanno’s intentions, Lutatius sailed to the Aegean Islands to battle the Punic navy on the morning of March 10, 241. Despite a brisk wind and a heavy swell, the well-trained Roman crews mastered both the elements and the enemy, whose men had been hastily recruited. Fifty Punic ships were sunk and another 70 ships captured with their crews. Due to the rough weather, an inordinate number of men likely drowned. A change in winds allowed the remainder of the Punic ships to raise masts, hoist sails and escape back to the Sacred Isle.

Rome Wins out in the First Punic War, But at Heavy Costs

With characteristic doggedness, Carthage at first was ready to continue fighting, but then reality sank in. The First Punic War effort was broken; the final decision was left to Hamilcar at Eyrx. With little prospect of staying supplied, Hamilcar sent heralds to discuss terms and begin negotiations. Rome demanded that Carthage evacuate Sicily and all the islands between Italy and Sicily and pay Rome a hefty 3,200 Euboic talents over a 10-year period. Carthage accepted and thereby ended its 23-year war with Rome, the longest in history up to that time. For Carthage, more woes lay ahead, as subjugated tribes revolted and unpaid mercenaries turned on their former masters.

For Rome, it was a glorious chapter in her epic history, marking the beginning of oversea conquests that would make the Mediterranean a Roman Sea. Sicily became Rome’s first province and Rome’s grain basket. In 238, the Romans annexed Corsica and Sardinia, as well.

The First Punic War had been fought in Sicily, on the waters of the Mediterranean Sea, and in North Africa. Rome, with its greater resources, superior land armies, and successful adaptation to naval warfare, emerged victorious.

The innovative corvus was a stopgap that bought Rome time to gain skill in training crews and building ships, which in the final battle in the Aegean Sea proved superior to those of Carthage. Likely the extra weight, position, and size of the corvus contributed to losses in storms. That Rome was able to recover from those catastrophic losses illustrates her extraordinary resilience.

Carthage, though, was far from finished. Hamilcar’s son, Hannibal Barca, would lay waste to Italy and become one of Rome’s greatest foes in the Second Punic War of 218 to 201.