By Mark Carlson

On the nights of August 21 and 24, 1939, two dark ships slipped out of the German naval base at Wilhelmshaven and turned west toward the English Channel. Forty-eight hours later they were well out into the broad Atlantic Ocean, safe from prying British eyes. They were two of the Kriegsmarine’s most innovative warships, the compact but powerful pocket battleships Admiral Graf Spee and Deutschland. Each was armed with six 11-inch guns and could range for nearly 10,000 miles, prowling the seas for vulnerable prey.

A week before Hitler’s attack on Poland, Germany was already preparing to initiate Grand Admiral Erich Raeder’s Plan Z, the daring surface campaign to destroy Britain’s military and commercial sea trade.

The two ships were the vanguard of what Raeder hoped would eventually be dozens of fast and potent cruisers and battleships that would disrupt and destroy the Allies’ sea lanes and starve England into surrender.

At the war’s outset, Britain possessed about 2,000 merchant ships and another 1,000 coastal vessels of less than 2,000 tons each. This added up to around four million tons of cargo capacity. Another three million tons came from countries conquered by Germany, while another million tons were being launched each year. Britain required about 55 million tons of imports— consisting of food, oil, cotton, wool, and other industrial products—to sustain it. Raeder’s goal was to sink more tonnage than Britain could endure and force the capitulation. In essence, his raiders had to sink ships faster than Britain could replace them. As events proved, Raeder was doomed to fail before he even began.

Erich Raeder, who had risen to command the Kriegsmarine after a career that went back to being a junior officer aboard Kaiser Wilhelm II’s yacht Hohenzollern to the post of chief of staff for Admiral Franz von Hipper’s battlecruiser force in the Great War, was a strong advocate of fast surface commerce raiders. They had proved successful during World War I, even if their impact on the outcome was negligible. The most successful surface raider was the light cruiser SMS Emden. In three months in the Indian Ocean, Emden sank two Allied warships and captured or sank 16 merchant vessels totaling 70,000 tons. Emden was undoubtedly Raeder’s inspiration for his vision of fast raiders running wild through Allied shipping. But he failed to give much credibility to the U-boat campaign of World War I. Although the U-boats were often hampered by the diplomatic need to appease neutral nations who violently opposed unrestricted submarine warfare, in 51 months the 371 U-boats sank 5,282 British, Allied, and neutral merchant ships totaling more than 11 million tons.

Ignoring this persuasive statistic, Raeder had convinced Adolf Hitler that a surface fleet was essential to victory at sea. In January 1939, he proposed his Plan Z, envisioning a huge fleet of battleships, heavy cruisers, and aircraft carriers that would roam and dominate the seas by 1948. Hitler had promised his fleet commander that there would be no war until at least 1944, giving Raeder a healthy margin of time to carry out his grand building program.

But in the summer of 1939, Raeder learned of the planned invasion of Poland. Even though there was little doubt that Britain would quickly become involved, Hitler forged ahead, disrupting Raeder’s carefully laid plans to build a huge surface fleet. Faced with a fait accompli, Raeder used what few large surface warships he possessed to support Hitler’s grand campaigns.

But Raeder was more of a tactician than a strategist, a remnant of his time with the battlecruisers under Hipper. He never developed a broad strategy, instead using his meager force in hit and run raids and attacks. Additionally, Raeder gave little thought to U-boats as a viable means of cutting the Allied sea lanes. But his greatest blunder was that he failed to recognize the nearly two decades of advances in aviation, marine technology, and radar that made a surface fleet more of a target than a threat.

His shortsighted dogmas condemned the Kriegsmarine to defeat.

Erich Raeder was not only up against the powerful Royal Navy, but the former First Lord of the Admiralty and later Prime Minister Winston Churchill, whose devotion to the Navy was close to reverence. Churchill gave the Navy all the support it needed to assure Britain’s survival.

The last thing Churchill and the Admiralty wanted was for the distinctive shape of a huge German battleship to come out of the misty horizon and open fire with its heavy guns on a helpless convoy of tankers and transports. A salvo of heavy 8-inch or 11-inch high-explosive shells screaming out of the sky like angels of death could be devastating. The thin-skinned merchant ships could be sunk in minutes, leaving their crews to flounder and die in the freezing sea. Germany’s powerful ships would be wolves in the fold, unstoppable and deadly.

Raeder lacked the strength and time to make a significant contribution to the Third Reich’s war aims, but he doggedly followed a radically shrunken version of his original raiding plan. His only advantage was that the Royal Navy was largely equipped with vessels that had been launched during or shortly after the Great War. They were mostly older, slower battleships and battlecruisers with a leavening of light cruisers and destroyers.

However, Raeder’s ships were all new, having been launched since 1931 and fitted with the latest naval technology and engines. They were for the most part fast, heavily armed and armored and were the equal of their larger British counterparts. But there were too few of them.

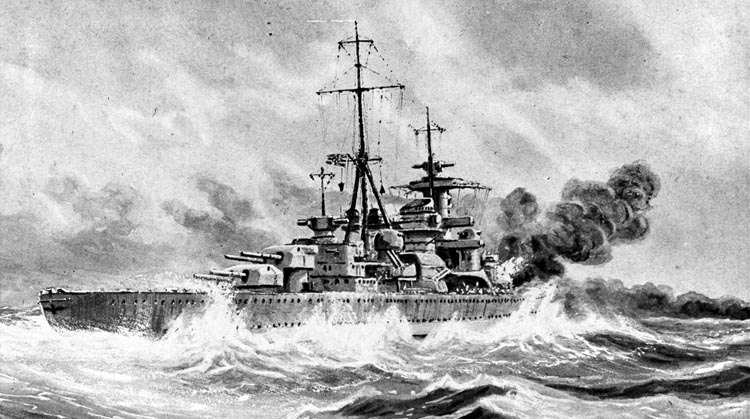

The numbers leave little doubt as to the inevitable outcome. Even at a fraction of its former glory, the British Home Fleet consisted of seven battleships, two battlecruisers, four aircraft carriers, 21 cruisers, more than 50 destroyers, and 20 submarines. The navies of Canada, New Zealand, and Australia added their own strength to this huge armada. Against this Raeder never had more than 10 powerful warships. Three were the so-called “pocket battleships” Deutschland, Admiral Graf Spee, and Admiral Scheer. In Germany they were officially called Panzerschiffen, or “armored ships.” They carried two triple turrets with six 11-inch guns. They were registered as being 10,000 tons each but actually displaced over 12,000 tons. Three 14,500-ton Admiral Hipper-class cruisers, Hipper, Blucher, and Prinz Eugen, each carried eight 8-inch guns in four turrets. Formidable in themselves, they were soon superseded by two larger vessels, which were called heavy cruisers but were in fact battleships. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, launched in 1936, each carried nine 11-inch guns in three turrets. While they were officially registered as displacing 19,000 tons, their registered gross tonnage was closer to 32,000. This made them larger than any German warship ever constructed up to that time, but Raeder was not finished. His planned armada was only partially complete.

The zenith of Raeder’s raider fleet were the huge new battleships Bismarck and Tirpitz, each of more than 50,000 tons and carrying eight 15-inch guns in four turrets. Launched in 1939 and 1940, respectively, the sisters were the largest and most heavily armed and armored warships ever built in Germany. But their very size and power made them the focus of Royal Navy attention even before they completed their sea trials. They were also the last capital ships built in Germany during World War II.

In August 1939, Raeder initiated Plan Z by sending Graf Spee and Deutschland out to sea. Graf Spee, named for Count Maximillian von Spee, commander of the German East Asia squadron in 1914, went to the South Atlantic, while Deutschland headed for the North Atlantic.

From the moment Graf Spee received word that Great Britain and Germany were at war, her captain, Hans Langsdorff, who was above all a gentleman warrior, began his hunt for British merchant ships. German raiders were under the strict rules of cruiser warfare, where all ships stopped must be searched and their crews allowed to escape in lifeboats before the vessel was sunk. His crew was skilled and loyal to their mission. Langsdorff used his ship’s reconnaissance plane to scout for prey. When Graf Spee came upon a likely ship, the first thing Langsdorff did was to destroy the merchant ship’s radio room with direct fire, preventing a distress call. Then he ordered the captain to abandon the vessel before he opened fire. Graf Spee sank 16 ships in three months of raiding in the Indian Ocean and South Atlantic. Not one person was killed or injured. But time and circumstances were catching up with Langsdorff.

Three British cruisers, HMS Exeter, Achilles, and Ajax, none of which had the firepower of Graf Spee, were under the command of Admiral Henry Harwood, a brilliant tactician. Harwood deduced that Graf Spee would head for the port of Montevideo at the mouth of the River Plate in Uruguay where a convoy was expected. On the morning of December 13, 1939, Langsdorff found the three Royal Navy ships converging on him. With few options, he chose to fight. While the three British cruisers had less firepower than their foe, they split up and forced Langsdorff to either concentrate on a single ship or split his own limited firepower. Graf Spee’s main armament of six 11-inch guns were in two triple turrets.

After only 20 minutes of battle, Langsdorff had severely damaged Exeter but suffered major damage to his own ship’s superstructure. The British guns could not penetrate his hull or turret armor. He chose to break off and attempt to make repairs in Montevideo. But the Uruguayan government would not allow him to stay long enough to make repairs, and in the end Langsdorff had to either face a more numerous and powerful foe or scuttle his ship. He stripped Graf Spee of all classified equipment and set off charges that sank her in the river.

Langsdorff and his crew then headed for Buenos Aries, where he later committed suicide.

Coincidentally Admiral Maximillian von Spee had died aboard his flagship SMS Scharnhorst only 1,000 miles from where his namesake would be scuttled almost exactly 25 years later.

Graf Spee’s sister, Deutschland, had a longer but far less successful career. Commanded by Captain Paul Veneker, Deutschland was operating off southern Greenland and Nova Scotia to interdict British shipping. At first she was moderately successful with two ships taken, but then Venaker made an error that caused great embarrassment to the Third Reich by capturing the American steamer City of Flint less than 1,200 miles from New York. The ship was seized and the American crew taken prisoner. Evading prowling British warships, Venaker headed for Norway. This was a further outrage, as both America and Norway were still neutral. The United States sent a flood of protests to the Nazi government.

Veneker then tried to go to Murmansk, but the Soviets, also neutral, refused entry. This meant that Deutschland and her crew were, in effect, kidnappers. Returning to Norway, Deutschland was boarded by Norwegian officials and the Americans set free. Deutschland returned to Germany for refit. To avoid any connection with the highly embarrassing incident, the ship was renamed Lutzow. Lutzow was heavily damaged by gunfire and torpedoes during the invasion of Norway the following year and towed back to Germany. Her luck failed to improve when the ship was again torpedoed by a Bristol Beaufort of RAF Coastal Command in June 1941.

Repaired, the ship then went aground off the coast of Norway, thus missing the famous July 1942 attack that scattered convoy PQ-17. By 1944, Lutzow nee Deutschland was providing support to German troops retreating from the advancing Soviets on the Baltic coast. Then an RAF Avro Lancaster heavy bomber dropped a 12,000-pound Tallboy bomb on the deck, doing great internal damage. Repaired once again, her ignominious career was ended when she was deliberately blown up four days after Hitler committed suicide in 1945.

Yet, as ineffective as Deutschland’s raids had been, she had managed to stretch the Royal Navy’s assets to the breaking point. Dozens of cruisers and battleships were detailed to protect the convoys from German raids, making things easier for Raeder’s plans but also rendering his goals virtually impossible.

Worse was in store for Raeder’s reputation. In November 1939, even before Graf Spee’s death ride, the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau found the armed merchant cruiser SS Rawalpindi in the region between the Faeroe Islands and the Denmark Strait. A small P&O liner of 16,700 tons, she was fitted with eight 6-inch and two 3-inch guns. Under the command of Royal Navy Captain E.C. Kennedy, the Rawalpindi savagely attacked the two big German battleships. Even while the small liner sank from dozens of heavy shell hits, her guns continued to fire. The action forced the two German raiders to leave the area before a heavier Royal Navy force arrived.

Almost exactly a year later, another converted liner, the 14,000-ton SS Jervis Bay, under Commander Edward Fegen, was escorting Convoy HX-84 from Bermuda to Britain. Admiral Scheer found the convoy off the coast of Iceland. Fegen charged at the German ship with her seven 6-inch and three 3-inch guns. Jervis Bay was sunk in 20 minutes. Fegen earned a posthumous Victoria Cross. The convoy escaped without loss.

Despite some victories, one factor Raeder could not ignore was that the German surface raiders needed fuel, ammunition, replacement parts, food, and other supplies as they roamed far and wide in their hunt for Allied ships. Tankers and freighters had to be stationed in neutral or friendly ports. The raiders could patrol no farther than a few thousand miles from a support vessel, further limiting their range and effectiveness. Raeder recognized that it would become increasingly difficult for any of his raiders to evade the Royal Navy and patrol aircraft.

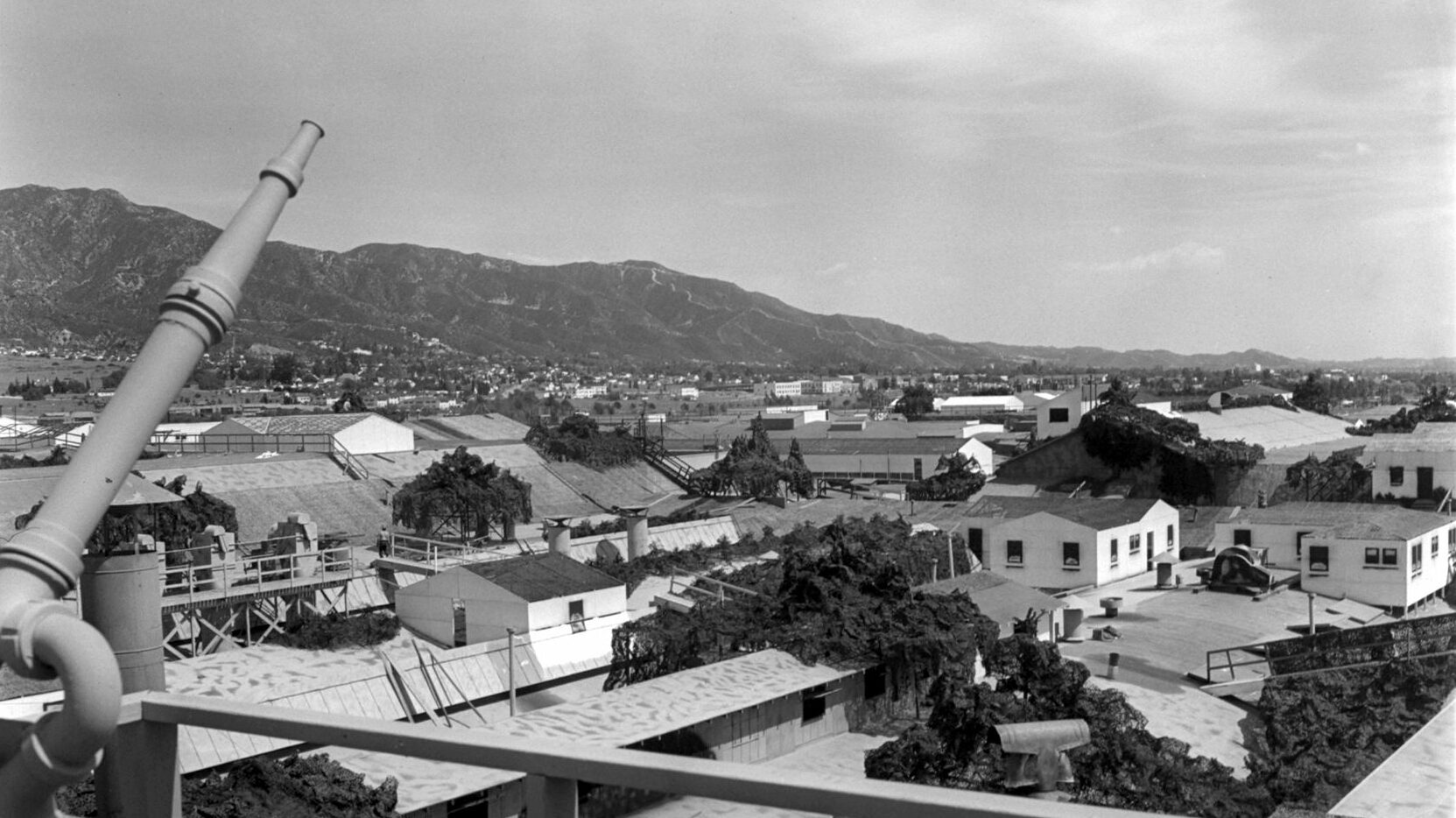

The other factor was geographical. Germany has only one coastline in the Baltic and North Seas. The major ports on the two seas are connected by the Kiel Canal, built in 1895 and expanded in 1913 to allow rapid deployment of ships, avoiding the long and often treacherous route around Denmark. But the fact was Germany could not deploy any ships without passing England either via the North Sea or through the English Channel. Raeder began to urge Hitler to invade Norway. This would provide dozens of fjords and harbors far up the North Sea from which to send his ships out to the Atlantic. Hitler, who had always considered the Norwegians to be a racially kindred nation with Germany, and seeing both strategic and tactical advantages to taking Norway, agreed. Raeder’s ships and transports were used extensively in the campaign, which began in April 1940.

The heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and four destroyers were escorting 1,700 troops to Trondheim when they were spotted and attacked by the British destroyer HMS Glowworm. Hipper’s captain first fired on the Glowworm and then attempted to ram, but the British ship turned the tables by ramming the larger ship, tearing a 100-foot rent in the hull. While Glowworm later exploded, Hipper needed extensive repairs. Another invasion unit consisting of the newly named Lutzow and Hipper’s sister Blucher was accompanied by the light cruiser Emden, namesake of the famous raider of World War I. They headed for Oslo, which was guarded by 40-year-old 11-inch guns purchased by the Norwegians from Krupp to defend the city. When the German ships were almost near enough to “see the whites of their eyes,” the heavy guns began firing. Blucher was so heavily damaged that she was easily finished off with torpedoes. More than 1,000 German seamen went down with her. Lutzow was also damaged but escaped. The big German surface ships had not played a major role in the Norwegian campaign.

The Royal Navy sent the carriers HMS Ark Royal and HMS Glorious, recently arrived from the Mediterranean, to support the defense of Norway. They were to recover the remaining RAF fighters and bombers that were now stranded in Norway. The captain of Glorious, a veteran of World War I, failed to have an air patrol watching for any attack as his ship landed the precious fighters and bombers. Then, vectored in by Luftwaffe reconnaissance planes, the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau raced in and began firing their 16 8-inch guns at the helpless carrier. Even with a smokescreen laid down by the escorting British destroyers, Glorious went to the bottom an hour later. This was the only significant warship, other than the battlecruiser HMS Hood the following year, to be sunk by German surface raiders.

With the fall of Norway in June 1940, Raeder had his North Sea sanctuaries for the raider fleet. Germany now controlled 3,000 miles of coastline from northern Norway to the Bay of Biscay, 10 times more coastline than before the war.

By the spring of 1941, Raeder was scrutinizing the total number of ships sunk in the first full year of war. Graf Spee had sunk 16 ships, totaling 50,000 tons. Admiral Sheer did better in the less heavily patrolled Indian Ocean, sinking 17 ships totaling over 113,000 tons before sneaking back to Germany in March 1941. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau managed to send 122,000 tons of ships to the bottom before being forced to run for a safe base in France.

The totals were not nearly as high as Raeder had promised Hitler.

And things were only going to get worse. Using radio direction finding (RDF) and brilliant cryptanalysis, the British Admiralty was tracking the raiders with ever-increasing skill. Long-range patrol aircraft, such as the American-built Consolidated PBY Catalina and its Canadian-built counterpart, the Canso, were scouring the Atlantic Ocean over the convoy routes. Added to this must be the work at Bletchley Park, where the German radio traffic was analyzed and distributed to the fleet. The Royal Navy was able to deduce the location and operational orders for Raeder’s ships. Every tanker and supply ship that was found and sunk further limited Raeder’s ability to find and attack the convoys.

But Raeder’s delusion that his few remaining ships could still do what he had envisioned in 1939 refused to die. He sent word to the newly operational Bismarck in April 1941, that she and her escort, the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, should move out of southern Norway and head to the Atlantic. His ultimate plan was to have the two ships join with the newer Tirpitz and the sisters Scharnhorst and Gneisenau to break into the Atlantic and hit the big convoys. His theory was that the two biggest warships could temporarily control and extend into regions of the North Atlantic with their speed and heavy guns. Bismarck, being the most dangerous, was to fight and distract the Royal Navy escort ships while the other German raiders sank the helpless merchant ships. But Raeder’s grand plan was never to materialize. Tirpitz was not yet fully operational, Scharnhorst was having her engines overhauled, and Gneisenau had been torpedoed in the harbor at Brest, France. All Raeder had left were Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. No destroyer escorts could accompany them on their sortie as their range was too limited.

Raeder had little choice. The British convoys were carrying the weapons and troops for the invasion of Crete in the Mediterranean. They had to be destroyed or disrupted. This was pure folly on Raeder’s part. The Royal Navy was well aware of Bismarck’s location and was keeping a close eye on her. Norwegians, resisting their conquerors, reported any movement of German warships and planes to their British allies. Raeder assumed, with some justification in light of Rawalpindi and Jervis Bay, that the Royal Navy was defending convoys with as few as one warship or converted liner.

Yet the Royal Navy was more than willing to strip protection from other convoys to provide extra firepower to destroy Bismarck. In all, the British force consisted of six battleships, four battlecruisers, two carriers, 13 cruisers, 33 destroyers, and dozens of patrol aircraft. This was the largest force ever tasked with the destruction of a single ship.

Even without the additional support of three other large warships, Bismarck was to sail in mid-May and wreak havoc on the convoys no matter what.

There is little need to detail the chase and sinking of Bismarck as it has been covered many times over the years. But it serves as an excellent example of bad planning, bad leadership, and bad judgment by both Raeder and the fleet commander, Admiral Guenther Leutjens, who commanded Bismarck and Prinz Eugen on their ill-fated attempt to break out to the Atlantic. Leutjens made some very poor decisions that not only sealed Bismarck’s fate but condemned nearly his entire crew to death without any hope of success.

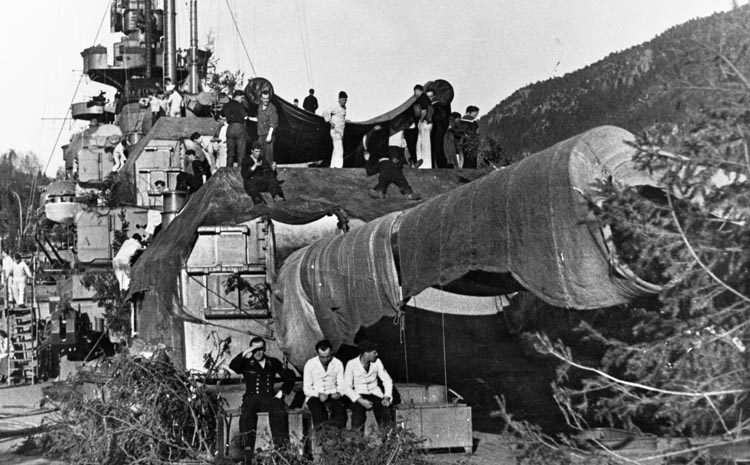

By the summer of 1941, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Admiral Scheer, and Admiral Hipper were all being repaired or under constant air attack. They were unable to find a way to escape their French and Baltic Sea prisons. Then there was the last big raider, Tirpitz. She was what Raeder called a “fleet in being,” a term for a single powerful ship dominating an entire region. That might have had some validity at the start of the war, but by late 1942 it was pure madness. But Tirpitz’s fearsome presence did reap some unexpected benefits for Raeder. When the Soviet Union joined the Allied cause, Churchill promised Josef Stalin that he would begin sending convoys carrying vital war material to the Russian arctic ports of Murmansk and Archangel.

By the end of 1941, the first seven of these, designated PQ and JW, made it through to their destinations unscathed, but soon the Kriegsmarine was able to take action. More surface raiders and U-boats were sent to northern Norway, and long-range Focke-Wulf FW-200 Condor planes were sent out to find the convoys. Then the Royal Navy received word that the huge Tirpitz, along with the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer and the cruiser Prinz Eugen, were being sent to Norway. This was ominous news, as they could only have one objective: the Murmansk convoys.

Prinz Eugen was spotted and torpedoed, forcing her into a port for repairs.

In March 1942, Tirpitz was sent out to interdict PQ-12, but bad weather made finding the convoy impossible. The battleship returned to the safety of the Norwegian fjord. The Royal Navy conducted several air raids against the ship, but none were able to get close due to heavy antiaircraft fire.

Convoy PQ-17 was assembled in Iceland. It consisted of 35 merchant ships, 22 of which were American. Their cargoes were composed of hundreds of tanks, aircraft, and trucks, as well as fuel, ammunition, and supplies badly needed by the hard-pressed Red Army in its desperate battle to stop the Germans. The escort was six destroyers and a covering force of four cruisers, two British and two American. Several Royal Navy battleships were sent out in case Tirpitz emerged from her Norwegian redoubt.

On June 27, PQ-17 set a course into the Arctic Ocean, well aware of the threat that could come from the many fjords and harbors along the enemy coast. The convoy was spotted by a Condor on July 1, and the U-boats closed in to sink two ships. Then the Admiralty received word via Bletchley Park that Tirpitz was refueling in a northern Norway port. This could only mean one thing: she was going to attack PQ-17. There was no way for the heavy battleships of the Royal Navy to get there in time to stop a bloodbath. Near panic ensued, and in a series of badly conceived orders, the covering cruiser force was to head west and the convoy was to scatter, each ship to make a run for Murmansk on its own.

The last transmission from the convoy escort commander was, “Sorry to leave you like this. Good luck. Looks like bloody business.” Convoy PQ-17 was now at the mercy of Doenitz’s U-boats and the Luftwaffe. Day after day they charged in with a savage fury. By the time the remains of PQ-17 reached Murmansk, only 11 of the original 35 ships were left. It was a costly debacle. It was also the German Navy’s greatest single victory against an Allied convoy. The truth was, Tirpitz was never sent out to the convoy, but merely fueling and shifting its berth. The scattering of PQ-17 served to show how much the Admiralty feared the power of heavy guns on a convoy. Yet neither Tirpitz nor any of the other surface raiders fired a single shot at the unprotected ships.

The turning point in the debate over the effectiveness of U-boats versus surface raiders was decided in favor of the former at the end of 1942. Early on, at Hitler’s insistence, Raeder had issued standing orders for the raider fleet. It stated that they engage at whatever cost, as long as they did not endanger or lose their ships. Even a casual reading of this order reveals its obvious contradiction. It ultimately led to Raeder’s fall from power.

In December 1942, Hipper, Lutzow, and six destroyers were sent from Norway to attack convoy JW-51B. The convoy consisted of 15 ships moving through the Arctic Ocean to Kola. The force was heavily escorted by seven destroyers and two light cruisers. Corvettes and air support from Murmansk were at the ready. When the German ships hove into view on December 31, they attacked the outer escort screen, sinking one minesweeper and a destroyer. But it was apparent that many more British warships were coming and further reinforcements had been called in.

The German commander broke off the action. Raeder’s order had also made it plain that if the German force was confronted with ships of equal strength they were to disengage. Not one freighter had been sunk. Worse, Hipper received three hits from 8-inch shells. The BBC announced the incident, and Adolf Hitler, never one to accept or recognize his culpability, went into a rage and ordered that all the remaining surface raiders be scrapped, their guns turned into coastal fortifications and their crews transferred to the U-boat fleet. In light of how poorly the surface raiders had so far served the Third Reich, this might have been a good tactical move.

Raeder resigned on January 30, 1943. The new grand admiral of the fleet was Karl Dönitz. The U-boats finally had the high command’s full support.

As for Tirpitz, she remained under heavy air and shore protection in Trondheim throughout much of the war, being subjected to numerous and costly air attacks by Royal Navy torpedo planes and land-based bombers. The only time Tirpitz, the last and most powerful battleship in the Kriegsmarine, ever fired her huge guns at the enemy was a shore bombardment of a British weather station on the island of Spitzbergen in September 1943. Fuel shortages prevented her from any further sorties, and the ship spent months sheltered in antiaircraft and antitorpedo defenses.

More Royal Navy torpedo planes and land-based bombers made attacks on Tirpitz through the summer and fall of 1944. The end finally came in November 1944, when Lancasters of No. 617 Squadron, the same group that had bombed the Ruhr Valley dams in March 1943, attacked Tirpitz with huge 12,000-pound Tallboys. Even though most bombs missed, there were enough hits to assure that the last German battleship would never leave port.

In the end, the mighty Tirpitz rolled over and sank in Tromso, Norway. No more surface raiders emerged from the Baltic or North Sea to threaten Allied shipping lanes.

After February 1943, the U-boats were the primary German naval weapon of the war. Altogether U-boats sank 2,779 ships for a total of 14.1 million tons, or 70 percent of all Allied shipping losses in all theaters of the war. The most successful year was 1942, when more than six million tons of shipping were sunk in the Atlantic.

As for the surface raiders, the total tonnage sunk by their guns was just short of 800,000. Considering the expense and the number of men needed to operate them, the results were dismal. The irony is that Raeder, who oversaw all new construction, was undoubtedly aware that for the cost, materials, and manpower of building just one battleship like Bismarck the Kriegsmarine could have launched at least 10 U-boats. If he had turned the Navy’s efforts to constructing submarines as far back as 1935, there could have been as many as 100 more U-boats manned and in service by 1940.

Churchill had openly stated that the thing that most frightened him during the war was the U-boat menace. Fortunately for the Allies, Raeder followed his own doomed plan. Of all the German surface raiders that put to sea in World War II, only one survived the war. The heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, whose sole claim to fame was accompanying Bismarck on part of her death ride, was captured by the Allies and ended up in the Pacific.

Prinz Eugen was made into a target in the Operation Crossroads atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in July 1946. While Prinz Eugen survived the two blasts, the sturdy cruiser was so totally irradiated that she had to be towed to Kwajalein Atoll and left as a derelict. She later turned over and sank. Her stern is still visible today.

This was the final blow to Admiral Erich Raeder’s fleet of surface raiders.

Author Mark Carlson has written on numerous topics related to World War II and the history of aviation. His book Flying on Film—A Century of Aviation in the Movies 1912-2012 was recently released. He resides in San Diego, California.