By William E. Welsh

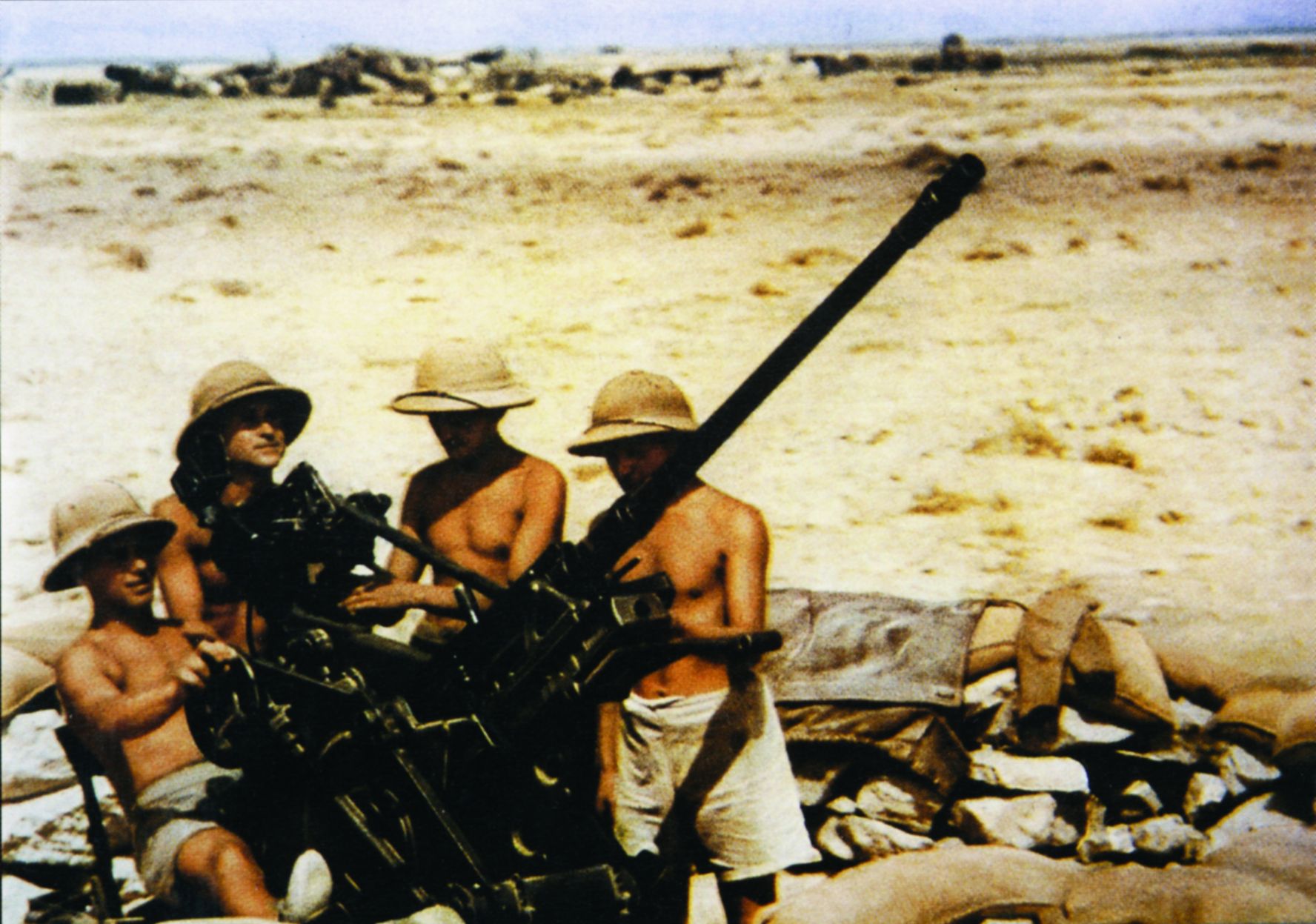

As the 33 men of his machine-gun platoon set up their four s along the ridge facing south toward a jungle-shrouded ravine on Guadalcanal where the Japanese were massing for an attack on the evening of October 25, 1942, Marine Sergeant Mitchell Paige crawled in front of their position and rigged a makeshift trip wire designed to alert his troops should Japanese forces approach their line.

Shells from Japanese howitzers on the west bank of the Matanikau River slammed into the ridge during a driving rain as Paige worked as quickly as possible. After the wire was strung, he placed C-ration cans at intervals on the wire and put an empty cartridge in each so that the cans would rattle if disturbed. He then rejoined his platoon and hunkered down to await the enemy assault.

Paige was born on August 31, 1918, and grew up in Charleroi, Pennsylvania. As a young boy growing up in the quaint town, Mitchell looked forward to the annual Armistice Day parade with a keen sense of anticipation. He deeply respected the veterans of the Great War who marched with pride along the town’s main street. He admired their ribbon-bedecked uniforms and dreamed of the day that he might go to war to prove himself in battle.

When he turned 18 in 1936, the broad-shouldered youth enlisted in the Marine Corps. The following year he shipped out to the Philippines. From there he journeyed in 1938 to Peking, China, where he joined the Marine detachment guarding the American embassy in the Imperial City. The Second Sino-Japanese War had begun the previous summer, and the Japanese were fighting their way deeper into China. During his tenure at the embassy, Paige served as an armed guard on supply trains shunting badly needed supplies from Shanghai to Peking. Riding on the train as it chugged its way through the war-torn Chinese countryside, Paige frequently saw Japanese soldiers willfully killing Chinese civilians. It was his first encounter with the ferocity of the Japanese Army.

Paige left the horror of the war in China behind in 1940. He was among the troops bundled into Maj. Gen. Alexander A. Vandergrift’s newly created 1st Marine Division. Sergeant Paige was assigned to Lt. Col. Herman H. Hanneken’s 2nd Battalion of the 7th Marine Regiment.

In April 1942, five months after the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, elements of the division deployed to forward bases in Samoa and New Zealand. Not long afterward, the Japanese began constructing an airfield on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. The move threatened the ocean supply corridor between the United States and Australia, and the Americans prepared to counter the move by capturing Guadalcanal.

Eleven thousand Marines began landing on Guadalcanal and the neighboring islands of Tulagi and Gavutu-Tanambogo on August 7, 1942. Japanese aircraft and warships counterattacked immediately. They drove off the American and Australian transports and warships in the waters off Guadalcanal, initially leaving the Marines to fend for themselves. Although the Marines had secured a beachhead and taken control of the airfield, which they renamed Henderson Field, the Japanese controlled the rest of the island.

The Marines had to make do on an island where the elements were as much an enemy as the Japanese. They lived in a primitive fashion in a harsh, tropical climate on an island that was mostly jungle except for the coconut groves along the shore.

The Japanese began probing the American perimeter between Lunga Point and the Tenaru River in late August. The Allies won the Battle of the Tenaru on August 21, as well as the large-scale battle known as Edson’s Ridge fought over three days in mid-September. Japanese reinforcements arrived on Guadalcanal via the Tokyo Express, a name the Americans gave to the troop landings conducted by Japanese destroyers, transports, and submarines. The landings were made at night so the vessels could not be intercepted by American aircraft.

The Americans expanded their perimeter in the first two months on Guadalcanal. On the west side, the Marines clashed twice with the Japanese in the Matanikau River sector. The actions in late September and early October were known, respectively, as the Second and Third Battles of the Matanikau.

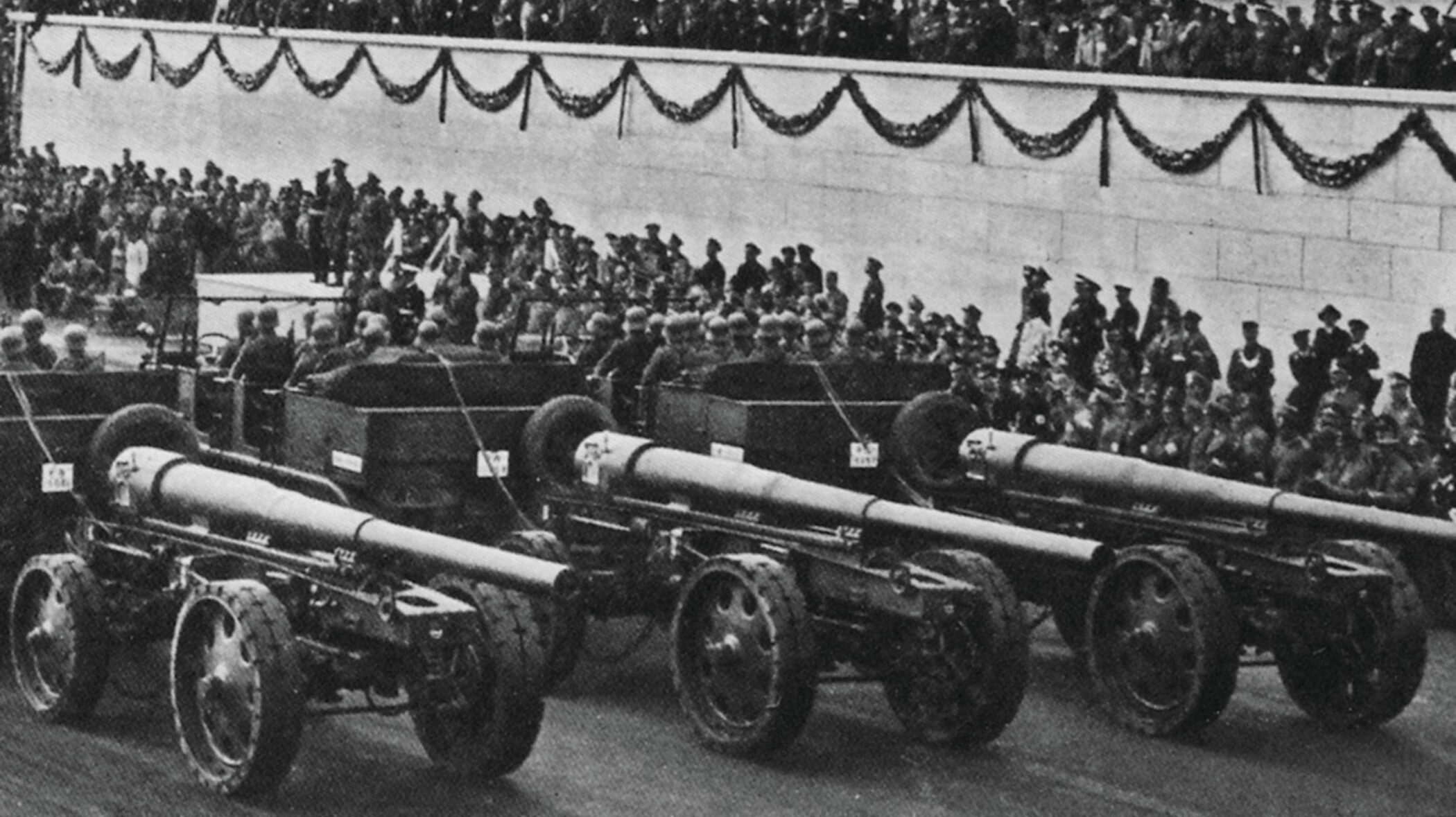

It was imperative that the Marines hold the Matanikau line, which included the sandy beaches along the coast, because it was the only possible route of advance from the west by which Japanese forces could employ tracked and wheeled vehicles. The sector was situated about four miles west of Henderson Field.

By mid-October, two Marine battalions, the 1st/7th and the 2nd/5th, held the high ground on the east side of the Matanikau near the coast. The Americans intercepted a Japanese map indicating that three Japanese divisions would attack the perimeter from three separate directions. Although the Americans spotted enemy forces building up to their west and south, there was no indication that they would be attacked from the east.

Colonel Akinosuku Oka, commander of the reinforced 124th Infantry Regiment of the Imperial Japanese Army’s 35th Brigade, received orders on October 19 to cross to the east bank of the Matanikau, attack the two Marine battalions defending the river line from the flank and rear, and secure the high ground on the east side of the Matanikau for further operations.

When the Americans spotted Japanese infantry massing in the thickly wooded ravines south of the Marine position on the Matanikau on the morning of October 24, Vandergrift ordered the 2nd/7th on October 25 to conduct a forced march from its position near Henderson Field to defend an east-west ridgeline against Oka’s expected attack. Sergeant Paige and his men fell in with the rest of the battalion as they tramped rapidly to their new position.

The 2nd Battalion arrived at its assigned position in the early evening of October 25. The Marines found themselves under bombardment not only by howitzers on the west bank of the Matanikau, but also Japanese destroyers positioned offshore. The three rifle companies were deployed from west to east, with Company E holding the lower of the two hills to the west, Company G on the saddle in the center, and Company F on the higher hill to the east.

Paige’s machine-gun section set up between Companies F and G. Paige personally positioned the guns to protect Company F to his left and Company G to his right. After the guns were in place, he strung the trip wire. The Marines soon began lobbing mortar shells into the ravine to inflict as many casualties as possible on the Japanese foot soldiers.

The Japanese struck Hanneken’s battalion at 3 AM on October 26. Company F was hardest hit. Vicious hand-to-hand fighting erupted on the battalion’s front line as the Japanese tried to dislodge them from the ridge.

When a Japanese soldier thrust his bayonet at Paige’s head, the sergeant threw up his left hand to block it. The razor-sharp blade cut deeply into his hand, nearly severing his fingers. In a lightning move, Paige drove his Ka-Bar knife into his attacker’s neck, killing him instantly.

During the fighting, the two Marine rifle companies positioned behind Paige’s platoon withdrew a short distance, isolating and exposing Paige’s machine gunners. The repeated charges by the wild-eyed, bayonet-wielding Japanese took a heavy toll on the 2nd Battalion in the hours before sunrise.

When one of the machine guns was damaged beyond use, Paige braved enemy fire to bring up another one. The members of Paige’s section fought valiantly, but the Japanese managed to kill or severely wound all of the men in the platoon expect Paige. In the third hour of the battle, Paige ran back and forth from one machine gun to the next in the darkness to deceive the Japanese into believing that there were still a lot of Marines on the ridge.

The Japanese ultimately succeeded in driving Company F from its position. As the Japanese swept past him, Paige remained at one of the guns. He swiveled it to the left and right, firing into shadowy figures that swept past his position.

The first flicker of dawn occurred after three hours of frenzied combat. The light of morning revealed a landscape blanketed with the dead and wounded bodies of American and Japanese soldiers. A lull settled over the battlefield at sunrise as Japanese officers rallied their men for a final assault.

Paige said the Japanese knew the lay of the land east of the Matanikau River very well and had a clear plan in mind when they made their attack. “They were hoping they could catch the Marines someday in a position like this where they could break through with enough people,” he said. “There were no obstacles behind me,” he said, adding that it was “just a straight shot through the coconut trees right down to the beach road.“

Paige devised a plan for deceiving the Japanese into believing that American reinforcements were on hand. He draped two cartridge belts over his shoulder, and with one cartridge belt in his Browning machine gun, he unclamped it. Cradling his machine gun in his left hand, he charged down the hill. Before he did so, though, he shouted, “Fix bayonets and follow me!” to the Marines of Company G to his right rear. Paige then charged down the hill toward the Japanese firing his Browning machine gun from the hip as he went.

Paige spotted a Japanese officer and his guards standing up in the kunai grass below him. “He was firing at me as I was charging at him. He had probably as many as 18 men with him…. As I bounced down the hill I raked them and they all fell over.” The officer, though, remained standing.

“The Japanese officer had exhausted his ammunition,” Paige recalled. “He threw his revolver to the deck, and he started to pull his samurai sword as I approached him from about four feet away. One burst of the machine gun came right down his face and chest and as his samurai sword started out, [it] hit the sword and the scabbard.”

At that time, the Marines to his right rear came charging down the hill with fixed bayonets. The executive officer of the 2/7 had scraped together rear-echelon troops and along with Marines from Company G, the Americans launched a counterattack, driving the Japanese back into the jungle. By that time, they knew the Japanese attack had been defeated and were yelling with joy. “It was the greatest sight I have ever seen in my life,” Paige said. Ninety-eight Japanese dead lay on the ridge and another 200 in the ravine.

The Japanese decided in late December to withdraw from Guadalcanal. The extraction was handled skillfully in the first week of February 1943. As many as 10,000 Japanese soldiers were loaded onto destroyers and removed to safety. During the Battle of Guadalcanal the Japanese lost 25,000 men compared to 1,700 American dead.

After Guadalcanal was secured in February 1943, Paige was promoted to lieutenant and transferred to Australia. Vandergrift presented him with the Medal of Honor on May 21, 1943.

In addition to the usual accolades set forth in a Medal of Honor narrative for “extraordinary heroism and conspicuous gallantry in action above and beyond the call of duty,” Paige’s citation mentioned that he had continued fighting with “fearless determination” after his gunners were all either killed or wounded. It described how he had shifted from one gun to another while maintaining a “withering fire against the advancing hordes until reinforcements finally arrived.” Lastly, it noted how he had spearheaded a bayonet charge that resulted in the Japanese withdrawal from his battalion’s sector. His valor was a reflection of the courage and bravery shown by the thousands of Marines who conquered Guadalcanal.