By William E. Welsh

The gray-clad Virginia infantry marched quickly through the woods. In the distance they could hear the familiar rattle of musketry signaling an encounter with the enemy. Few had time that autumn day to appreciate nature’s colorful display of red and yellow leaves in the upland forest.

Although not immune to the unsettling feeling that gnawed at the stomach of even veteran troops before a battle, the Virginians had already weathered their baptism of fire at First Manassas exactly three months earlier. That experience would serve them well in the unfolding clash at Ball’s Bluff on October 21, 1861.

Taking Command of Confederate Forces

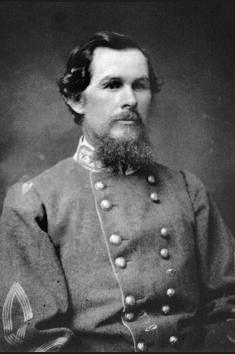

By the time 39-year-old Colonel Eppa Hunton arrived with his 8th Virginia Infantry at Margaret Jackson’s farm less than a half mile from the Potomac River, other infantry and cavalry were engaged in a heavy skirmish. As the senior officer present, Hunton took command of the Confederate forces on the field.

A native of Fauquier County, Hunton had served for the past 12 years as commonwealth’s attorney for Prince William County. He lacked any formal military training or significant military experience, although he had served in the Virginia militia. An ardent secessionist, he had raised the regiment at the beginning of the war. For that effort, he was given a commission as the regiment’s colonel on May 8, 1861.

“Tell Hunton to Fight On”

Hunton struggled with severe ailments throughout the conflict. He was on sick leave at home when it became apparent in mid-October that a fight was brewing for Colonel Nathan “Shanks” Evans’ brigade, to which the 8th Virginia belonged, which had been assigned to defend Leesburg. “I put my bed in my wagon … and lying down made my trip to Leesburg,” wrote Hunton.

After the 8th Virginia became engaged at 12:30 PM against a Union force of unknown size, Hunton sent repeated requests for reinforcements to Evans. But Evans was monitoring other developing Union threats, and it would be two hours before substantial reinforcements arrived in the form of the 17th and 18th Mississippi Infantry Regiments. To one of the first requests, Evans said, “Tell Hunton to fight on.” To one of the later requests, Evans said tersely, “Tell Hunton to hold his ground till every damn man falls.”

Mississippi Regiments Arrive; Hunton Rallies

When the Union regiment against which he was engaged pulled back at 2 PM, Hunton followed closely on its heels, keeping up pressure on the Federal force. He used the terrain and cover of the woods to his advantage. “I was assailed repeatedly during the day and had to fight hard to maintain this position,” Hunton wrote. When his men ran out of ammunition, he ordered bayonet attacks.

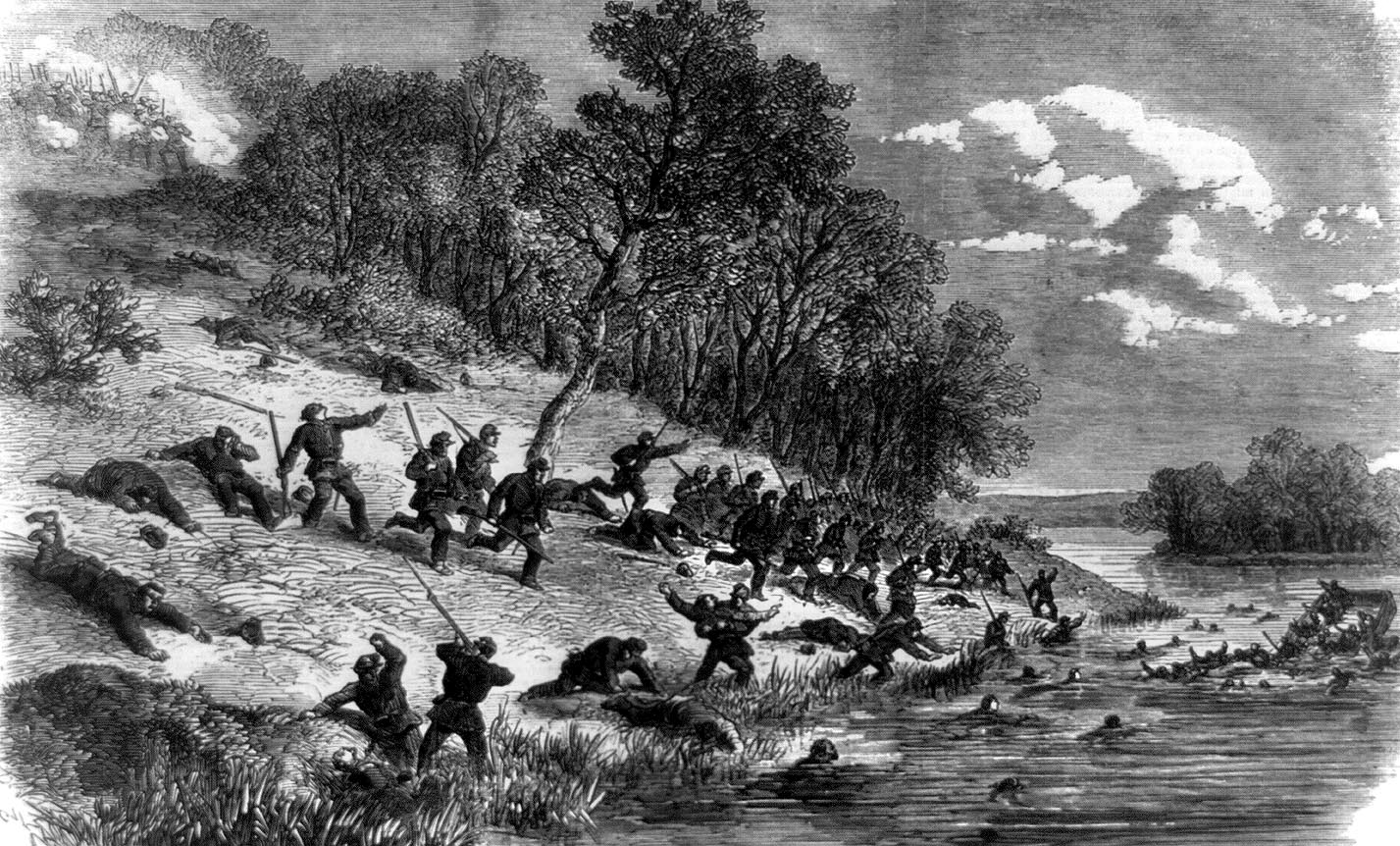

The battle heated up with the arrival of the two Mississippi regiments. An attack by the 1st California Regiment disrupted Hunton’s 8th Virginia late in the battle. But Hunton rallied his command and led it back into battle. The Virginians played a key role in routing the Yankees, who lost a large number of men attempting to cross the river to safety.

Promoted to Brigadier General

Afterward, Hunton would lead Brig. Gen. George Pickett’s brigade through the remainder of the Seven Days Battle after Pickett was wounded at Gaines’ Mill. He also would lead Pickett’s Brigade at Second Manassas. While leading the 8th Virginia in Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, Hunton was wounded in the right leg.

During his convalescence, Hunton was promoted to brigadier general. Hunton’s brigade fought at Cold Harbor and at Petersburg. On the retreat west from the Richmond-Petersburg sector, Hunton and most of his brigade were captured in the Confederate defeat at Sayler’s Creek on April 6, 1865. After several months in a Union prison, he was allowed to swear an oath of allegiance to the Union and return home. He breathed his last breath in Richmond on October 11, 1908, and is buried in Hollywood Cemetery.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments