By John Wukovits

Prim, proper, and lacking any trace of braggadocio, the first lady of the United States, Eleanor Roosevelt, preferred placid pastimes and exchanging letters with close friends. She had gained the respect of her nation during the dark Depression days, when her perky spirit and concern for the suffering of her nation buttressed the steps her husband, Franklin D. Roosevelt, implemented to yank people from misery and back to the mainstream.

At the opposite end of the spectrum stood Admiral William F. Halsey. The man loved action, the more intense and desperate the better. Like the first lady he, too, had earned the devotion of his country, but not for being sweet. During the war’s initial months, when the Japanese amassed triumph after triumph in the Pacific against a seemingly helpless United States, Admiral Halsey stood amid the shambles and illuminated the way to victory.

Interspersing a combination of bold actions and profane declarations Halsey, like Franklin Roosevelt, lifted a nation from despair. His command in numerous operations, including raids against Japanese-held islands, the Doolittle Tokyo Raid in early 1942, and his dramatic turnaround of American fortunes at Guadalcanal in late 1942, placed the “Bull’s” image on magazine covers and his photograph in every major newspaper.

The two would be brought together in late 1943 when Eleanor Roosevelt traveled to the Pacific to visit troops stationed in Australia and on tiny islands sprinkled across the South Pacific. Some of those islands, the scenes of bitter combat from August 1942 and into 1943, lay in Halsey’s domain, and the last thing the dogged warrior wanted was to be distracted from his chores by a visit from a high-ranking dignitary. As far as Halsey was concerned, she wanted nothing more than to make political capital, and with men fighting and dying throughout the South Pacific he had no time for political gamesmanship from the wife of his commander-in-chief.

The president first brought up the notion of the Pacific trip. Eleanor had already visited Great Britain, and Franklin felt that similar recognition should be accorded to the people of distant Australia and New Zealand. Those countries had been under the threat of Japanese attack since Pearl Harbor, placing their leadership and citizens under enormous pressure, to which they had nobly responded.

They had also hosted thousands of U.S. servicemen who passed through both places on their way to Pacific battlefields. In addition, Eleanor had received scores of letters from women in Australia and New Zealand asking her to travel to their countries and witness the significant contributions the local women had made to the war effort.

Eleanor agreed but asked her husband if she could include Guadalcanal and other South Pacific areas on her itinerary. The president demurred, but Eleanor claimed that her trip to Australia and New Zealand would lose meaning “if, when I was to be in the Pacific area anyway, I were not permitted to visit the places where these men had left their health or received their injuries.”

FDR faced a dilemma. He wanted Eleanor to visit the Pacific but not be a problem for his top commanders in their efforts to defeat the enemy. In an effort to pass the buck, he sent letters to General Douglas MacArthur and Halsey expressing that while the final decision on the itinerary was theirs, “I would not have you let her go to any place which would interfere in any way with current military or naval operations—in other words, the war comes first.”

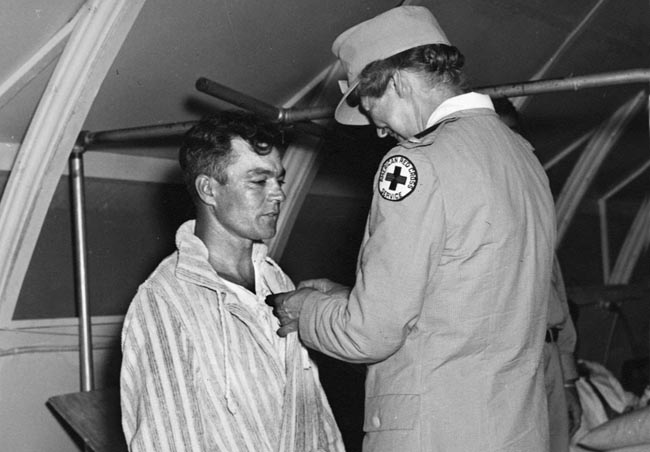

To prepare for her trip, Eleanor visited Norman Davis, chairman of the American Red Cross, to ask if she might examine the different Red Cross installations along the trip. She believed that doing so might make the trip more meaningful, as well as provide material with which to counter critics who contended that the trip was nothing more than a public relations move for the White House or that she would occupy valuable space on aircraft. Davis, who had been thinking of sending a representative on an inspection tour of the Pacific, happily agreed and urged Mrs. Roosevelt to don a Red Cross uniform during her journeys. Eleanor liked Davis’s suggestions. A uniform would negate the need to pack multiple outfits, thereby saving cargo space on aircraft, and she admitted she would feel more comfortable visiting hospitals and service clubs if she were in uniform like the personnel about her.

Her sons, all in the military, offered advice as well. They urged her to avoid eating only with officers and to share repasts with enlisted personnel whenever possible, even if it meant rising earlier in the day when the privates and corporals sat down for a meal.

“This trip will be attacked as a political gesture, & I am so uncertain whether or not I am doing the right thing that I will start with a heavy heart,” she wrote her friend Joseph Lash on July 25, 1943. “I’ll try to do a good job on seeing the women’s work & where I do see our soldiers I’ll try to make them feel that Franklin really wants to know about them.”

On August 23 Eleanor departed San Francisco in an unheated four-engine Army B-24 Liberator bomber, sharing space with military personnel and sacks of mail from home. She confided in her newspaper column, “My Day,” that she hoped to bring to readers, particularly mothers, “a feeling that they have visited the places where I go, and that they know more about the lives their boys are leading.”

After a lengthy flight, Eleanor landed at Pearl Harbor on August 23, where she was driven to the home of Brig. Gen. Walter Ryan to enjoy fresh pineapple and other fruits from Ryan’s garden. From Pearl Harbor she flew 1,400 miles south to her first stop along what her husband called “the islands for guarding the supply route”—Christmas Island. After supper on the island, Eleanor retired to her room for the night but found the floor nearly covered with bugs. After stamping her foot a few times, the bugs disappeared through cracks in the floor.

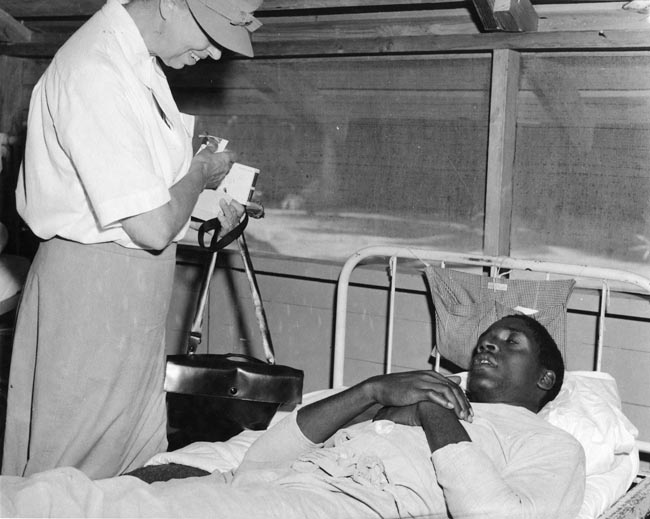

Following an all too brief sleep, which became common for her during the trip, Eleanor inspected installations and visited hospital wards. She stopped at each bed to briefly chat with the recovering soldiers and sailors and asked for the names and addresses of family back home so she could write a note to them. She drove 40 miles to visit one isolated camp, where she enjoyed a warm welcome. One correspondent wrote that Mrs. Roosevelt reminded the soldiers more “of some boy’s mother back home than the wife of the President of the United States—and we all loved it.”

The flight to her next stop—Cook and Samoa Islands 1,600 miles to the southwest—tested the ability of the pilot and navigator to locate such tiny plots of land amid the vast ocean. An impressed Eleanor wrote in her newspaper column, “Our navigator seemed to me nothing short of a miracle worker, for how he hit these little dots without any deviation in course I wouldn’t understand. Nothing but waves and small fleecy clouds would be in sight, and then someone would point and there would be the island.”

Her routine for each stop seldom varied. She visited the military installations and hospitals as soon as possible and usually joined the troops for the nightly movie before retiring to her quarters to finish a newspaper column. “I was introduced again and we saw a good movie. The movie industry is certainly doing well in supplying the troops with films. I did a little typing after I returned to quarters, then packed, chased away some disagreeable and very large red bugs that came up through the floor boards, and went to bed.”

Unwelcome critters proved to be an issue at most of her Pacific stops. She awoke one morning to find a rat scampering across her bed, another morning avoided a python that lay curled on the floor, and learned that crickets joined the rats in tearing into any item of clothing left in the open.

In the Fijis, the first lady used her brief time to inspect the facilities, visit with the troops, and see what help she might offer. She concluded that the men stationed in the Fijis needed more recreation equipment, and when told that four soldiers recently died from drinking distilled shellac she urged that the men be allowed beer and wine.

Following suggestions from her sons, she arose early each morning so that she could eat breakfast with the enlisted men and gain insight into their attitudes and needs, and whenever she spoke to an assembled unit she kept her remarks brief so they would not suffer in the blinding sun.

She did not have to strain to discern their opinion about the enemy. “No one out here has any pity for the Japanese,” she wrote during the trip. “They have seen them do too many things which we consider beyond the pale of civilized practice. Human life to a Japanese seems to have no value.”

Eleanor became so enamored with the men that she chafed whenever a commanding officer surrounded her with guards. She once complained to her husband that the generals and admirals assign so many guards that “I remind myself of you,” but she could also not help but notice that her presence presented a problem to commanders who had to disrupt their daily schedules to arrange for her welfare and protection.

“In some ways I wish I had not come on this trip,” she cabled her husband from one stop. “I think the trouble I give far outweighs the momentary interest it may give the boys to see me. I do think when I tell them I bring a message from you to them, they like it, but anyone else could have done it as well and caused less commotion!”

The visits to the hospitals, where she talked with men suffering from ghastly wounds, posed severe challenges to her ever present cheerfulness. She hoped to bring a bit of joy into their lives but feared that men who had been too long away from female companionship would prefer a Hollywood beauty or pinup girl.

“Over and over again on this trip I wished that I could be changed in some magic way into the mother or the sweetheart or the wife or sister that these men longed to see,” she wrote after the trip. She was happy to bring a touch of home and to let them know that she and her husband, their commander-in-chief, were thinking of them, but she worried that her visits were far from “adequate when you know so well what the boys really want and you can do nothing about it.”

She eventually realized that her appearances were an elixir to the troops. Her beauty may not have matched that of Betty Grable or Lana Turner, but she provided something far deeper—a sense of home and mom. “Over here she was something,” said one soldier after her visit, “none of us had seen in over a year, an American mother.”

She chatted happily as men in the Red Cross rooms, mess halls, and hospital wards gathered to exchange a few words with the most prominent mother in the United States and to relay a common request—once she returned home, would she get in touch with mothers, wives, or sweethearts? She promised each soldier to do so.

After the Fijis, an aircraft whisked Eleanor to Noumea and her first wartime encounter with Admiral Halsey. To that point Eleanor believed she had accomplished some good with the battle-scarred troops. Would that continue once she was in the company of the nation’s most revered Navy officer?

She had a right to be concerned, as the crusty Halsey considered her visit to be a waste of his valuable time. Even though he had met Eleanor Roosevelt before and admired her, he was now busy fighting a war, and the last thing he wanted was to be wrenched from that task to babysit the first lady. He chafed that he had to divert aircraft from the Solomons fighting to escort her plane to Noumea and that he would have to “play the gracious, solicitous host. I had no time for such folderol, yet I’d have to take time.”

Eleanor arrived in Noumea wearing the Red Cross uniform that became a trademark of her visit to the war zone. She and the admiral politely greeted each other, and when Eleanor asked Halsey’s advice on which locations she ought to visit the admiral suggested she spend two days in Noumea, leave to tour New Zealand and Australia, and return for another two-day visit in Noumea before heading back to the United States.

Mrs. Roosevelt then handed Halsey a letter from the president asking that, if the admiral considered it safe, could the first lady be permitted to visit Guadalcanal, the scene of savage fighting in late 1942 and early 1943. When Halsey answered, “Guadalcanal is no place for you, Ma’am!” Eleanor replied, “I’m perfectly willing to take my chances. I’ll be entirely responsible for anything that happens to me.”

Halsey explained that he needed every fighter plane he had in the combat zone, and a trip to Guadalcanal would force him to divert aircraft from where they were most needed to escort her to the island. He did add, however, that after she returned from Australia he would reevaluate the issue, a comment that lifted Eleanor’s spirits.

“I realize final responsibility is his,” she later wrote to her husband, “but I feel more strongly than ever that I should go & I doubt if I ever go to another hospital at home” if she could not visit the wounded at a place that had become synonymous with courage and sacrifice.

The next morning Eleanor embarked on a full day of visits. She inspected Noumea’s installations, delivered brief speeches, and made herself available to the troops, both in and out of the hospitals. She took time to chat with those recovering from their war injuries, bringing broad smiles to their faces when she asked about their well-being and about their families. Though weary from her trip, whenever a soldier flashed one of those smiles “I would feel that the endless miles I walked every day were worthwhile.”

She cheered men with horrid head wounds or with an arm or leg missing and was uplifted by the soldiers’ positive outlooks. One man who had lost his right arm in combat boasted to the first lady that he could already tie his shoes with his left hand, and other hideously wounded soldiers were more concerned for their families and their military comrades than they were for themselves.

She pinned the Navy Cross on Navy Lieutenant Hugh Barr Miller who, after his ship was sunk, evaded patrols on a Japanese-held island for 39 days. At one hospital, she stopped by the bed of a boy whose stomach was so gruesomely shot up that doctors doubted he would survive. Eleanor leaned over and kissed him gently before leaving, and to the surprise of all he started to improve.

Halsey’s reticence over Eleanor’s visit softened the more he learned of and observed the effect she had on the men. He admired her nonstop pace, and “When I say that she inspected those hospitals” Halsey wrote, “I don’t mean that she shook hands with the chief medical officer, glanced into a sun-parlor, and left. I mean that she went into every ward, stopped at every bed, and spoke to every patient: What was his name? How did he feel? Was there anything he needed? Could she take a message home for him? I marveled at her hardihood, both physical and mental; she walked for miles, and she saw patients who were grievously and gruesomely wounded. But I marveled most at their expressions as she leaned over them. It was a sight I will never forget.”

Halsey was not the only military commander the first lady impressed. Maj. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, a Medal of Honor recipient for his able command skills that guided the defense of American positions on Guadalcanal and helped turn the tide, knew something about weariness from observing his fatigued Marines during the Guadalcanal fighting.

After watching Mrs. Roosevelt make repeated stops to wounded soldiers despite being exhausted from the long flight to Noumea, he called her “a remarkable woman” who “spent the bulk of her time in New Caledonia visiting our sick and wounded, talking to them by the hundreds. In each case she took the man’s home address and upon her return to America wrote his family.”

The best testimonial may have come from a member of the medical staff, who wrote a friend back in the United States that people at home criticizing the cost of her trip did so out of ignorance. The first lady’s positive effect on morale more than compensated for any fuel expended or costs absorbed.

He wrote, “As far as our bunch is concerned, we would all be willing to turn over our pay for the rest of the war to help compensate you fellows on the home front for any inconvenience you suffered by Mrs. Roosevelt’s trip.”

From Noumea Mrs. Roosevelt flew to New Zealand, accompanied by Commander H.D. Moulton, one of Halsey’s aides, and by Maria Coletta Ryan, a top Red Cross official. Sir Cyril Newall, the governor general marshal of the Royal Air Force, Mrs. Fraser, wife of the prime minister, and other officials waited for them at the Auckland airport, where Eleanor broadcast a brief radio speech before speaking to a throng of newspaper reporters.

Her dawn-to-dusk schedule in New Zealand mirrored that of previous stops. Hospitals, Red Cross clubs, and camps became her domain, and she drove hundreds of miles across the country to speak to soldiers and Marines in training camps. She attended official receptions, including a tea at the home of the governor general, and gave dozens of speeches to crowds large and small. She especially enjoyed her tours of war factories, where hundreds of female workers labored alongside men to produce the weaponry needed to defeat the Japanese.

After most exhausting days, she typed her 400-word column, “My Day,” that appeared in stateside newspapers. “The outstanding thing to me is how such a small number of American Red Cross personnel with New Zealand volunteers ever has done the work and met the needs of the great number of men in this area,” she wrote for her column that appeared on September 3.

She loved interacting with the soldiers and made certain to emphasize that they were not forgotten at home. She relayed a message from her husband that he followed their actions every day and admired the sacrifices they endured for their nation.

Each day, Eleanor saw examples of the toughness of American youth, especially those lying in hospitals with grievous wounds. “Every now and then I have to smile when I think of people who thought that a younger generation was growing up at home and, in fact, in many countries, which could not meet physical hardships,” she wrote from Auckland in one of her columns.

“Let me assure you that no pioneers ever were sturdier than this generation. In addition, I must pay tribute to their fortitude in pain and discomfort. Invariably a sick boy will say, ‘I’m getting on fine.’” She stated that soldiers often brought up their girlfriends with her and reminded them of the impact their letters had upon young soldiers so far from home and family.

She added that she would love to arrange reunions, “but since I can’t, I am telling you girls at home so you won’t forget what your letters mean out here, and how hungry boys are for news from you.”

A fear she harbored before leaving on the journey briefly flared in New Zealand. Eleanor had heard the disconcerting but false rumor that she had urged her husband to place in quarantine for six months every Marine who had been in the Pacific before they returned home, out of fear that they might be unable to control their sexual impulses. The president admonished her to ignore the story, but despite its absurdity, the unfounded rumor appeared when a Red Cross worker remarked that a few Marines opposed her visit for that very reason.

“Heaven knows how it started, but it plagued me for a long time, and a similar story was told in all parts of the world.”

She took her husband’s advice and focused on bringing good cheer and encouragement to every soldier and Marine she encountered. Her exuberance and decency quickly dissolved any doubts that men may have had about her. After listening to one speech, a soldier remarked, “Her sincerity permeated every word. I can tell you that after a year of listening to nothing but bassooning top sergeants and officers, it was good to hear a kind lady saying nice things.”

Major George Durno accompanied Mrs. Roosevelt on many of her stops and was equally impressed with the impact she made, not only on the soldiers, but also on the people of New Zealand. “Mrs. Roosevelt literally took New Zealand by storm,” he said. “She did a magnificent job, saying the right thing at the right time and doing 101 little things that endeared her to the people.”

Time magazine enhanced the praise for the first lady in its September 13 issue, telling home front readers that Mrs. Roosevelt charmed everyone she met. “If Franklin Roosevelt was looking for a U.S. ambassador of good will, he could have made no better selection. Indefatigable Eleanor Roosevelt attended receptions, teas, dinners, visited U.S. servicemen in hospitals and clubs, saw noted Pohutu Geyser at Rotorua, N.Z., autographed a wounded Marine’s leg bandage, got christened ‘Queen of the Great Democracy’ by Maori chieftains, won friends and influenced people everywhere by her untiring kindness.”

The magazine added, “She was a forthright, energetic, middle-aged lady and she was more exciting than anything the antipodes had seen in many a down-under moon.”

After sweeping New Zealand by storm, Eleanor Roosevelt boarded a transport for the flight to her next stop—Australia and the controversial commander, General Douglas MacArthur.

Any worries that she may have harbored about meeting General MacArthur were allayed on September 3, 1943, when she arrived to a warm reception at Mascot Field near Sydney. The previous month, MacArthur had told one of his top commanders, Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, to arrange the greeting and itinerary for Mrs. Roosevelt’s visit to Australia, while MacArthur remained in New Guinea.

Although MacArthur gave the excuse that he was needed closer to the front during a key part of his campaign against the Japanese, most observers believed he ducked out of meeting the first lady due to his political antipathy toward her husband. Eichelberger wasted little time executing his task, “But I viewed my assignment with apprehension. Commanding a corps seemed easier.”

Thousands of Australian civilians jammed the airfield to welcome Mrs. Roosevelt. People tossed flowers and cheered as she made her way from the plane to the terminal.

Another whirlwind schedule awaited. Her event-packed days included frequent stops at hospitals and military recreation centers, Red Cross installations, and receptions. She visited three major cities in five days, often driving through streets lined with cheering Australians and children waving American flags. Newspapers compared her reception to the one given to the Duke and Duchess of York—subsequently King George VI and Queen Elizabeth of England—in 1927.

While her presence may have grated MacArthur, the troops considered her visit a sign that their country had not forgotten them. She told a group of sailors at one naval installation that her husband “asked me to be sure to take his greetings to American men fighting everywhere and tell them how proud he is of their splendid spirit.”

Soldiers handed her photographs and asked Mrs. Roosevelt if she would relay them to their families; at a stop at one hospital, a wounded soldier asked if she would call his girlfriend when she returned to the United States to let her know he was all right.

Eichelberger was a registered Republican who had not voted for her husband, but Eleanor won him over with her exuberance and untiring cheerfulness: “I shared an airplane with her on 3,000 miles of travel, and my legs ached as I walked with her through hospitals and Army camps. In hospitals she stopped at beds to talk with soldiers and wrote down messages to send to families.”

She walked into every hospital corridor and stopped at every bed, where she listened to their complaints, scribbled notes on what she might do to assist the young men, and bolstered their morale with a cheering phrase.

“She was indifferent to personal hardship, and always gracious,” wrote Eichelberger. “She could not be kept out of wards where wounds smelled evilly and agony was a commonplace. These were the men, she said, who needed comfort the most.”

One time in Queensland, Mrs. Roosevelt spotted a convoy of Army trucks loaded with troops. When Eichelberger told her that the soldiers were leaving Australia for the combat zone, she asked the driver to catch up to the convoy so she could wish them good luck. When she reached the convoy, she stopped at each truck and spoke to each soldier.

“She trudged down the rough road, her shoes dusty and scarred by rocks, pausing by each truck long enough to speak to eager-faced soldiers in full battle dress,” wrote a New York Times reporter traveling with the first lady’s group.

“At one point her voice quavered, but she quickly recovered and continued on down the line. She insisted on returning on the other side of the line to wave to those she had missed.”

Before her visit ended, the avid Republican general was an unabashed admirer of the first lady. Eichelberger wished that every American could have witnessed what he observed during the few days in Australia, for then they would have seen the obvious impact she had on the troops. He wrote, “It will be hard for people to understand how warming it was for a sick or wounded or well soldier in a foreign land to see the wife of the President of the United States at his elbow.

“It made him, 10,000 miles away from his childhood, confronted with unknown and incalculable future dangers, somehow feel remembered and secure. And perhaps, in some mystic way—and I do not want to sound sentimental—Mrs. Roosevelt served as his own mother’s deputy.”

Two aspects bothered Eleanor. She believed that the heavy escort that accompanied her throughout her Australian visits kept her from meeting as many ordinary citizens and enlisted men as she wanted. She wanted to step over to crowds more frequently, but General Eichelberger was under strict orders from MacArthur in New Guinea to keep her safe. She wrote to a friend that everyone treated her “like a frail flower and won’t let me approach any danger.”

That led to her second disappointment—MacArthur’s veto of her desire to travel north to New Guinea, the scene of fierce combat throughout 1942 and into 1943. MacArthur’s denial surprised Eleanor, who worried that soldiers would incorrectly assume she avoided New Guinea out of fear. “The boys last night all asked if I wasn’t coming to New Guinea,” she added to her friend, “and I feel more strongly than ever about their restrictions.”

MacArthur claimed he denied Mrs. Roosevelt’s request because New Guinea was too dangerous, but a bit of home front politics shaded the matter. The 1944 presidential campaign approached, and with a burgeoning movement back home to nominate MacArthur as the Republican candidate gaining momentum, the general preferred not to be photographed with Mrs. Roosevelt. As a substitute, on September 13 Mrs. Jean MacArthur, the general’s wife, hosted a lavish dinner for Eleanor.

As her visit in Australia neared an end, Mrs. Roosevelt fretted that she had accomplished little good, but she was unable to distance herself from her actions and see the positive impact she made on everyone at each stop.

The United States ambassador in Canberra, Nelson T. Johnson, later wrote the first lady, “You gave to Canberra and Australia not only the thrill that comes from a visit of royalty but the intellectual thrill of realizing that they were meeting a very fine woman with a very warm personality of her own.”

MacArthur aide Captain Robert M. White, who was assigned to accompany Mrs. Roosevelt, was at first perturbed that he had to leave headquarters to escort the first lady. He wanted to fight the enemy, not escort dignitaries, but he altered his opinion. He later wrote, “Wherever Mrs. Roosevelt went, she wanted to see the things a mother would see. She looked at kitchens and saw how food was prepared. When she chatted with the men, she said things mothers say, little things men never think of and couldn’t put into words if they did. Her voice was like a mother’s, too.

“Mrs. Roosevelt went through hospital wards by the hundreds. In each she made a point of stopping by each bed, shaking hands, and saying some nice, mother-like thing. Maybe it sounds funny, but she left behind her many a tough battle-torn GI blowing his nose and swearing at the cold he had recently picked up.”

General Vandegrift needed no more convincing: “I had dreaded her coming, but I knew when she departed that she had been the most valuable VIP who had ever come to Australia. Her simplicity and lack of side endeared her to the troops; her graciousness endeared her to the Australians; and her visit stored up a reserve of good will that was like a family bank account.”

Eleanor wrote, “There is an island in the Pacific which symbolizes for many people the type of living and working and, above all, the fighting our boys have done in this field of war.” She said that about Guadalcanal, an island that the home front equated with heroism. She believed that if she traveled thousands of miles to the South Pacific without visiting the island that she could never again look a wounded soldier, sailor, or Marine in the face.

When she returned to Halsey’s Noumea headquarters after her visits to New Zealand and Australia, she held little hope that the admiral would approve a trip to Guadalcanal. Even though the bitterest fighting had moved to islands to the north, the Japanese still occasionally bombed Guadalcanal. However, reports of Mrs. Roosevelt’s positive impact on the military altered Halsey’s opinion, and though he still had his doubts, he agreed to the trip.

“When I saw her off,” Halsey later wrote of watching the first lady’s airplane lift off toward the island, “I told her that it was impossible for me to express my appreciation of what she had done, and was doing, for my men. I was ashamed of my original surliness. She alone had accomplished more good than any other person, or any group of civilians, who had passed through my area.”

Her plane stopped first at Efate in the New Hebrides, northeast of Noumea. After visiting the wounded—“It seemed as though I walked through miles of hospital wards,” she wrote—she reboarded the aircraft for the hop north to Espiritu Santo, the northernmost island of the New Hebrides, about halfway from Noumea to Guadalcanal. “There are thought to be some Japs still on the other side of the island and there are still air raids,” Eleanor later noted.

When she arrived at Guadalcanal, she shared breakfast with General Nathan Twining, the commanding officer of the Thirteenth Air Force. As Army trucks whisked her away to hospitals, she passed vehicles loaded with Seabees and waved to them. “Gosh, there’s Eleanor,” said a startled Seabee.

A group of 50 Marines, most naked, were washing in a stream when Eleanor’s vehicle drove by. Most leaped into the water, but three sailors who were unaware of the occupant shouted for a lift. When they jumped in and realized they were looking at the first lady, they quickly fell silent. Eleanor broke the awkward tension and chatted about home as if nothing unusual had occurred.

More somber moments overshadowed the fleeting joviality. Like every other civilian back home, Eleanor had been insulated from the realities of combat. A list of casualties printed in a newspaper was one matter, but the mangled products of battle at first hand in the tents of Guadalcanal personalized the battle. She no longer perused a casualty list, but sat with young soldiers missing arms or legs and blinded sailors who would never again see their loved ones.

“It is unbelievable how young some of these boys are,” she scribbled in a diary she kept of her visit to Guadalcanal. Openly moved by their stoic acceptance of their wounds, she added, “but the responsibility of war matures them quickly.”

She marveled at their humility and at their denial that they were heroes. She chatted with men who had risked life and limb to rescue a wounded buddy and, to a man, each claimed they had done nothing more than what any other soldier would do. Instead of talking about heroics, the wounded preferred to discuss home, girlfriends, movies, sports, and parents.

“Over and over again on this trip, I wished I could be the mother, wife or sweetheart whom the boy really longed to see,” she wrote shortly after touring Guadalcanal. “Since that was not possible, I hope that someone who came from home, who often knew and could remember something about the particular place that was home to him, brought the people and the country which he loves a little nearer.”

As she did at every stop, she made certain to ask if any of the boys had messages she could deliver to loved ones once she returned to the United States.

What most remained with her, however, were the images gathered in the many hospitals and the solemnity that emanated from the makeshift cemeteries she too often came across. Helmets hung from rough-hewn wooden crosses marked many graves, and printed words—“He was a grand guy” or “Best buddy ever”—showed that other soldiers grieved his passing.

She wrote, “As you look at the crosses row on row, you think of the women’s hearts buried here as well and are grateful for signs everywhere that show the boys are surrounded by affection.”

After what could only be deemed a successful sweep through the South Pacific, Eleanor Roosevelt started on the long journey back to the United States. During a stop in Hawaii, she made a deal with one severely injured soldier that if he promised to try his hardest to recover she would visit his mother upon her return home. Eleanor subsequently saw his mother, and the soldier recovered from his wounds.

A brief layover in San Francisco allowed her to have lunch with her granddaughter before flying across the country to New York on September 24.

The exhausted first lady—she lost 30 pounds during her travels—could look back on a triumphant trip. She had traveled almost 26,000 miles since beginning her voyage on August 17, almost six weeks earlier, had visited 17 islands and nations, including 11 days in Australia and eight in New Zealand, and had toured military installations at Hawaii, Guadalcanal, New Caledonia, and other important locations along the United States military pipeline.

She had seen an estimated 400,000 men in different hospitals and camps. She admitted that she was exhausted “emotionally as well as physically,” but that she left the South Pacific with “a sense of pride in the young people of this generation which I can never express and a sense of obligation which I feel I can never discharge.”

She made a legion of friends among the soldiers. Actress Una Merkel, who followed her to the region, said that the soldiers were always asking her, “How’s Eleanor?” Film star Gary Cooper answered the same queries by replying, “Well, we saw her tracks in the sand at one of the islands where we stopped, but we couldn’t tell which way they were headed.” A movie short released the following month in 9,000 theaters heralded her accomplishments in bringing the nation’s well wishes to their soldiers, sailors, and Marines.

She kept every promise made to soldiers to visit or telephone their families, often receiving incredulous reactions before a family member realized the caller was, indeed, the first lady. When Miss Helen Carl, a government secretary, received a phone call stating that it was the White House calling, she assumed it was a joke until she recognized Mrs. Roosevelt’s voice. “I met your boyfriend, Sergeant Al Lewis, in Australia and he asked me to call and say hello!” said the first lady to a speechless Miss Carl.

Mrs. Roosevelt was determined to do much more than simply contact families, for she had seen too much to remain silent about the future. During the flight home she wrote copious notes for her husband on what she saw and hoped to have done, especially on postwar planning, to ensure that the veterans would not be forgotten once they returned to peacetime pursuits. She wanted legislation passed for jobs and education and planned to promote assistance for those who were physically handicapped from their wounds.

She said, “After the war we will have more handicapped men among us than we have ever had before. These kids’ whole lives will depend upon their being made to feel that they can live and work normally. We must give them the feeling that we are still dependent upon them, for if we do not do this we will kill the thing in them that makes life worthwhile.”

Claiming that the nation had an obligation to think of the postwar period and the welfare of the soldiers once they returned home, she wrote that the true memorial for those who perished in the conflict “must be built where we live by the way in which we make our lives count. We must build up the kind of world for which these men died.”

She added, “Long ago a man told me the big thing men got out of a war was the sense of shared comradeship and loyalty to each other. Perhaps that is what we must develop at home to build the world for which our men are dying.” She explained that both Australia and New Zealand had already begun outlining the plans for absorbing the thousands of military who would one day return and the steps for smoothly making that transition.

The two principal characters in the tour—the first lady and Admiral Halsey—emerged with elevated opinions of their counterpart. Halsey made it a point to praise the courage and stamina Mrs. Roosevelt displayed at each stop and said her appearance instantly bolstered the morale of every wounded man, whose expressions brightened as the first lady approached their cots.

“I watched the expressions on the faces of the patients, many of whom were grievously wounded. That sight made me change my opinion of the value of her visit immediately. She accomplished more good in less time than any single person or delegation of persons who visited my area during my entire tenure of office in the South Pacific.”

Eleanor responded with equal praise: “I will never forget Admiral Halsey’s hospitality to me, nor how grateful I was for his kindness and thoughtfulness at his headquarters in the South Pacific,” she wrote in her column.

When Halsey passed away from a heart attack on August 16, 1959, while vacationing on Fisher’s Island off Connecticut’s shore, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote in her syndicated newspaper column that his death was “a real personal loss. He was a courageous, able, and fine leader in the Navy.”

A pair that had once considered each other as nuisances had, through personal contact, become mutual admirers.