By Mason B. Webb

BACKSTORY: After Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Britain and France declared war on Hitler’s regime. Britain sent the 13-division British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to France and Belgium in anticipation of a German invasion, but for the next eight months there was virtually no fighting—a period known as the “Phony War.”

The war became real on May 9 and 10, 1940, when more than two million German soldiers, accompanied by thousands of panzers and aircraft, plunged violently into France and Belgium and pushed the BEF and some French units to the English Channel coast and the port city of Dunkirk. There, while under constant attack, over 330,000 troops managed to be evacuated back to Britain (Operation Dynamo).

In the early 21st century, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) embarked on a massive project to invite veterans to send in their personal wartime remembrances. There are now 47,000 stories in the WW2 People’s War archive. Scores of them detail what happened during the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force and French troops in late May and early June 1940. Here are but a few.

Bernard Styles joined the Territorial Army (the equivalent of the U.S. Army National Guard) in 1938 at the age of 18 as a member of the 4th East Yorkshire Regiment, which was part of the 150th Brigade of the 50th Northumbrian Division. After war was declared on September 3, 1939, his unit was part of the almost 395,000-man British Expeditionary Force (BEF) that was sent to France in January 1940 to counter an expected German invasion.

Styles said, “On arrival in France, we were moved around and finally finished in a small village called Annoeullin in the area between Arras and Lille. When the German assault started, we moved to form a defensive line north of Arras on the banks of a river. In the following action we lost our Command Sergeant Major and one officer due to mortar fire.

“We then started a staged withdrawal, leapfrogging other units up towards the Belgian frontier. We crossed into Belgium in the area around Roubaix, but before we had been deployed the Belgium government surrendered and we had to change our line of withdrawal. I can still see all the white flags hanging out of house windows as we were left stranded.

“Our withdrawal continued through Menin on the road to Dunkirk. The division was forming part of the eastern defensive lines along with a Guards division, and the leapfrogging retreat continued.

“We eventually arrived and formed the eastern perimeter of the defense around Dunkirk. On the first of June we were told that if the Guards held the perimeter we could withdraw, and we arrived on the beaches at Bray-Dunes. As daylight broke, we could see the deserted beach with the lines of vehicles that had been driven into the sea to form improvised jetties.

“We slowly moved down the beach to Dunkirk, taking cover when German aircraft appeared to strafe the area. I and several other companions gradually drew nearer to the Eastern mole [concrete pier] of Dunkirk harbor, helping to bring dead bodies out of the sea as they were being washed up.

“We arrived at the mole in the early morning of the 2nd of June and started to walk along it in the ‘hope’ we might find a boat. We were amazed to suddenly hear a voice shouting out, ‘I am not stopping—if you can get aboard, jump!’ We looked over the mole and saw a small paddle steamer six to eight feet below slowly reversing out of the harbor. We leapt aboard—in all, I think about 25-30 of us got aboard.

“When we spoke to the captain, he said that he had come over with himself and the chief engineer and no crew, as they were all shattered by their previous visits and would not come again at that time.

“We arrived in Dover and were relieved of our weapons and put aboard a train after being given drinks and food by the civilian helpers together with the postcard to address to our family to inform them of our safety.

“We arrived at Aldershot into a tented camp where we were issued with the standard necessities. After two to three days we were visited by Anthony Eden [former Foreign Secretary, now Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs, and future Prime Minister] who gave us a speech about what had happened, and the future. We went on leave, and on our return we formed into small sections to put up tented camps in parts of the south to accommodate the reforming units of the BEF.”

After the evacuation, Styles became a member of the 101st Royal Marine Brigade’s code and cipher unit.

Bren gunner James Bradley was sent to France near the Belgian border in September 1939. “When we first arrived in France,” he said, “it was like peacetime. But then Hitler struck at the Belgians and the Dutch, and we moved forward. We took everything and dashed into Belgium.”

But, outnumbered and outgunned, the BEF was quickly driven back. Bradley recalled, “They said that we were to get a rifle and a bayonet and after that we were on our own. We had to get back to Dunkirk. If they’d told us to get back to New York, I couldn’t have been more surprised because I didn’t know where Dunkirk was. I began to think to myself, I’ve got to survive—I must survive to fight on in this war.

“Eventually I did get to the coast. When I came to the sand dunes, I could see that Dunkirk was a blazing mass of burning oil and a battle was going on. I moved along the sand hills to Le Panne, a little to the right of Dunkirk, and there were hundreds and hundreds of soldiers on the sand. Ships were coming in, trying to pick up the soldiers.

“I saw the most magnificent bit of British discipline there. They went down in the water, stood in rows of four, and the tide came in and then the tide went out, and then it came back again…. There was the odd guy who left for obvious purposes—to nip back over the sand dunes. Then he’d come back and a hand would go up and someone would say, ‘Over here, over here!’ It was terribly British. I think I became a man there.

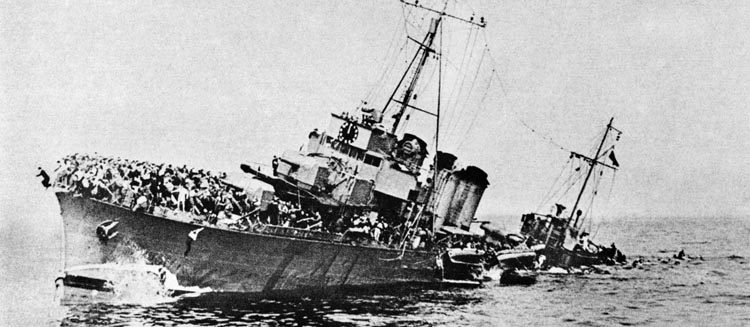

“Unfortunately, the dive bombers were knocking out the ships and terrible things were happening. I saw them hit a destroyer, packed with men on board, and it went on its side. Hundreds of men went into the sea, thrashing about there—many of them couldn’t swim, I’m sure. The next morning, there were dead lying about. Nobody could do anything about that, but there were some lads moving around, and some badly wounded.

“A little ship came along—it looked like a Dutch coaster, a real old tub. Those on board stopped, shouted, and waved. I thought this was the time for us to move on, but somebody said, ‘No, no, they’re waving at us to tell us to stay where we are.’ They lowered some small boats down to the sea and rowed inshore. We had to get into one of these little boats, which should have taken about three people but there was about eight of us in it—the waterline was getting near the top.

“They dropped a rope ladder down the ship’s side, and we had to climb up that. Some of the chappies were so weak they fell back in the sea. So they threw ropes down and tried to tie them and pull them up.

“A dispatch rider was behind me, and I thought he must be mad because he was wearing a tin hat, a rifle, and all his equipment. If he fell into the water, he wouldn’t have stood a chance. He moved around in front of me, and there was no panic. It must be done calmly, I thought. If we’re going to get there, let’s do it like real men. Then he fell in the water. I shouted to him but he went down. Bubbles were coming up, and he just went down, down. I couldn’t do anything.”

One soldier, Reg Gill of the Royal Army Medical Corps, recalled, “All our faith was in the Maginot Line which, the French said, was impregnable. We had our own army there, small by proportion, but we felt it would probably continue much the same course as World War I—eventually we would win. I mean, Britain always did win, and Britain and France together would surely win, but things were nasty.

“The Germans had broken through in the Ardennes, which is wooded country, hilly, impossible, so people said, for tank warfare. For that reason it had been very lightly defended. The Germans broke through against a division or two of the French territorial army with very little opposition. From then on things got rapidly worse.

“The Germans swept through north-central France, in a wide arc this time, heading not for Paris but the Channel ports, in a circular movement that took them rapidly down to Abbeville and to the coast just north of Rouen. They then proceeded to advance up the coast, which put us in a very difficult position.

“This was only one branch of the German army. The rest of it advanced towards central France, but as far as we, the British army in northern France, were concerned it looked very sinister indeed.”

Eric Cottam, 2nd Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment, said, “The battalion was allocated 10 Bren gun carriers. All infantry regiments wanted drivers for the carriers and, since I fancied a pair of carrier driver’s goggles, I joined the carrier platoon. We were a very happy crowd, and we had great fun before the war, driving across country and through woods—yes, I enjoyed that. We all more or less drifted into the army. Even though war was looming, it didn’t seem to worry us. We considered ourselves immortal—as most young people do.”

Cottam’s unit was sent to France, near the Belgian border. “This was the ‘Phony War’ period—then, over the winter, it became serious…. My battalion was involved building tank traps and constructing pillboxes. That was hard work, especially in bad weather.

“Our work was wasted. The Germans simply bypassed all the tank traps, which was very unsporting of them, after all the time we’d taken to develop them. I think they also more or less bypassed the Maginot Line when they came through the Ardennes, which was meant to be impassable. Hitler surrounded us, and the retreat started. We were lured into Belgium, and then the Germans closed the trap. We had to get out. The Belgians packed up, and the French on the right collapsed—it was chaos.

“Things were made worse by lack of sleep and lack of food. The cookhouse shop was blown up so we had make do, living off the land. We used to scrounge at deserted farms for chickens and things like that, and we went into houses to find food, even butter that had gone off, and stale bread. We had to boil the water because of the threat of disease, but sometimes we found coffee, which was great.

“We couldn’t see a thing in the streets so we didn’t know what was going on. We didn’t have a radio or anything like that. We were isolated from the battalion, so we were on our own, obeying orders to go here, there, and everywhere. We had to do a lot of travelling at night.

“Then there were the refugees—we couldn’t go forward because they were crowding the road. They didn’t seem to know where they were going. They were disorientated because the front line was so fluid (modern warfare had come as a surprise to a lot of people). I felt sorry for them because they had been so cheerful when we arrived.”

Eventually Cottam and his company closed in on Dunkirk after spending several harrowing days on the road being chased by German aircraft. Suddenly, his company was hit by an artillery barrage. “I dived in front of my carrier and landed by the left-hand track. Then I saw a mine. It exploded about 12 inches to my left-hand side…. Most of the explosion went over me, taking the track off my carrier and wrapping it over the top of the cab like silk ribbon. The explosion also took my left foot against the carrier side.

“I sat up when the barrage stopped. My left foot had gone, with my boot on it. There was blood everywhere. My face was a mess, and I thought my eye had gone. I put my right hand over my right eye and I found I could still see out of the left, so that was a relief. It turned out there were slivers of shrapnel in my face. My right leg was also a mess, bloody and shattered, but the foot was still there. Then I realized that the knee joint was turned completely round, which was serious.”

Cottam was put into a truck and evacuated to a casualty clearing station, where he received a transfusion and some emergency surgery before being sent on to Calais, which was being shelled. He never made it to Dunkirk but went straight across the Channel to Dover for months of recuperation in hospitals.

Stanley Mewis was a private in the 658th General Construction Company, Royal Engineers. After war was declared, Mewis and his company were sent to France. He said, “Our purpose for going there was a huge landing field which was under construction; this was to bomb Germany from France, but it turned out to be the other way. However, nothing much was happening, and it was called the ‘Bore War’ until activities started. Belgium at this time was neutral, and as soon as Germany attacked Holland, Belgium withdrew their neutrality and we marched into Belgium, which we all thought was a huge mistake.”

The BEF reached Belgium but then was ordered to fall back to Dunkirk. “On the march back from Belgium, all the dikes were flooded, and we were knee high in water. We weren’t allowed to rest, and we only kept small packs and our rifles. We were all very exhausted.

“We were amongst the first troops into Dunkirk, and I remember this long line of cars, staff cars, lorries, and cycles stretching to the horizon. They had just come off the boats for delivery, and the order was to smash the lot, and that’s exactly what we had to do—destroy the lot of them so the Germans couldn’t get hold of them—millions and millions of pounds worth of them.

“The Germans had hit a large oil storage tank at Dunkirk and there was a great cloud of smoke and flames 500 foot high; all the troops were told to make towards the smoke and that’s Dunkirk. When we got to the docks, there was a huge boat in the harbor, and we all shuffled forward three at a time. As we got to within 50 yards of the gangplank, it went up because [the ship] was full. I was then back on the beach.

“The Germans constantly came over bombing us. They had realized what was happening so they went on to bomb the docks day and night for eight days. Finally, there was no docks at all, and we had to take to the beach. We were formed in queues up to our neck in water, and we had to keep our cigarettes and matches in our helmets to keep them dry.

“Luckily the seas were calm, and we eventually got away, but not without further drama. The docks had been destroyed, and the larger ships couldn’t drop anchor—they had to form a large arc out of the harbor in the bay, so they were sitting ducks for the bombers. They couldn’t get any closer in so there were small boats plying between them and us, which was why we had to queue up in the water. When the tide came in, we had to back up, [but] those behind wouldn’t back up, so there were some nasty scenes. It was orderly at first and then became very disorderly.

“However, I managed to get a boat 150 feet long…. We got on, but unfortunately the skipper had come in too close and we got stuck on the bottom. There were about 150 of us on the boat. It was an empty shell inside, and we were ordered to run from one side of the boat to another to rock it whilst the skipper reversed the engines. The incoming tide was too much, and we had to abandon ship and jump into the sea. By the next day it was a blazing wreck; the Germans had hit it in the night.

“That was my first attempt. At the second attempt we got on an old British destroyer—HMS Wakeful—luckily; I was one of the last on board, and we hadn’t got hit up to that time. We were just pulling up anchor, and I remember the sun was going down and a great cheer went up from the troops on board.

“We went out about three miles when we were hit by a torpedo in the middle of the ship. The ship didn’t sink immediately—it just folded up. There were about 850 men below who didn’t get out…. I was thrown into the sea and was picked up by a small powerboat and put back on the beach.

“It was the lowest day of my life. I was so depressed to be back where I started on the beach…. I had been there six, seven nights. We were very thirsty and very hungry. Finally this small powerboat came along very close to the shore … and he picked about 15 of us up. Luckily, the Germans weren’t interested in the smaller craft, and we came straight across to Dover. There were 92 of us got back out of a total of 600; most were taken prisoner in Belgium.”

Another soldier, who identified himself only as “Fred,” said that while his unit was in Belgium, “The Germans overran us, and we had to retreat. We were sharing the roads with thousands of refugees, people with carts, hand barrows, anything they could use to carry their belongings. The roads were completely blocked by this human tidal wave so that we couldn’t get through in our trucks.

“Eventually, it was decided that we should abandon the vehicles and field guns. We went into a field where a senior officer told us we would have to spike the guns so that the Germans wouldn’t be able to use them.

“A shell was rammed into the breech, then another shell put in behind it, so that the first would explode inside the gun. We had to stand well back as the shell exploded and shattered the barrel. When we had spiked all the guns, we were told we would have to walk to the coast, to Dunkirk….

“When we arrived at Dunkirk, the Germans were shelling the beaches. The only thing we could do was to dig a hole in the sand and get down as low as possible. It gave a bit of protection from shells exploding on the surface.

“After a couple of hours in these holes, a young subaltern came down the beach. He said, ‘Now lads, I’m afraid it’s every man for himself. You can either wade out into the water and try to get onto one of those small boats, or you can try to get to La Panne. It’s about seven miles along the beach. There are two destroyers there. They will wait for you. If you want to, you can try to get there. The choice is yours.’”

Fred and another man decided to walk. “It was hard going, walking through the soft sand, but at last we reached the pier where the destroyers were berthed. There were some military police at the end of the pier. They were very brave men. They stood there as the shells were dropping all round, directing people, telling them where to go, helping everyone.

“They told me and my mate to stop and to get down behind the breakwater, which was made of stone. They said they would give us the nod when to run, then we should sprint to the end of the pier and get onto one of the ships as fast as we could.

“Eventually, they gave us the nod, so we ran to the end to HMS Venomous. A young lad was firing a machine gun at the planes overhead which were dropping bombs. We were still carrying our rifles, so he told us to throw them onboard first. Mine hit the side of the ship and dropped into the water. That was terrible. I could have cried. I had struggled with it through seven miles of soft sand, only to lose it like that.”

Fred and his buddy went below, where a young sailor gave them a bottle of brandy, and they had a good drink. “I think we must have slept, because we woke up in Dover.”

The British sometimes went to extremes to maintain order on the beach. Albert Henry Powell, a lorry driver in the Royal Signals, recalled, “We were marshalled in groups of 50, under an officer or senior non-commissioned officer (NCO), and marched down to the water’s edge. A beachmaster, who called each group in turn, maintained discipline there. I saw one group run out of line, and the person in charge was promptly shot by the beachmaster.”

Douglas Gough, a 20-year-old member of the Royal Artillery, recalled, “Down on the beaches were groups of soldiers just waiting—for what? I didn’t know then. Off shore could be seen the wrecks of several small craft and two or three larger vessels and debris lying all around. Off to my left I saw plumes of thick black smoke and the remains of oil tanks burning.

“I made my way down on to the beach, and no sooner had I got there I heard the sound of approaching aircraft. They were back again—the enemy planes flying low over us and bombing and machine-gunning everybody. Everyone dived into the sand, and some began trying to dig themselves deeper into it.

“I ran towards the sand dunes and lay flat. It was terrible. I tried to bury myself, absolutely helpless…. When [the planes] had gone, I got up and had a look around. I saw many wounded and dead lying around. The sounds of men crying and shouting will stay with me for the rest of my life.

“I appeared to be OK. I saw some stretcher bearers appear from the large buildings on the sea front; they took some of the wounded there.… Some officers were trying to organize us into groups of about 50 ready to board whatever vessel arrived at the beach next. Some units had managed to stay complete. I saw no sign of any of my regiment.

“Until I spoke to some of the other lads, I had no idea that we were being taken home to the UK. My impression had been that we were going to be landed at some other part of the coast to fight again. It was May 30th, and I was unaware that by now many thousands were already back in the UK.”

Harry Osbourne, a civilian sailor, took part in the rescue by the “Little Ships.” He said, “They came from Portsmouth, Newhaven, Sheerness, Tilbury, Gravesend, Ramsgate, from all along England’s southern and southeastern coasts, from ports big and small, from shipping towns and yachting harbors.

“Some, from up river, had never been in the open sea before. They were manned by volunteers; men who, without being given the details, had been told that they and their vessels were urgently needed to bring soldiers home from France. Most were experienced sailors—professional or otherwise—but many were fledglings who knew nothing about maritime hazards.

“Our route to Dunkirk was by no means direct as we had to keep to swept channels free of mines. In any case, there were so many craft of all shapes and sizes making for the same destination that we needed only to follow the fleet. My vivid and lasting impression of this stage of the operation is of a calm, flat sea covered with an armada of assorted ships and boats.

“The troops were very well disciplined, just waiting in long columns, hoping to be taken off. They were all dead beat, having had a terrible time fighting their way to the beaches. We were able to get right to the sandy beach and took on board about 30 British soldiers…. We rowed away from the shore and took our ‘passengers’ to the nearest craft lying offshore that we could find, a tug, a drifter, a trawler, anything that could risk coming in so close.

“We returned to the beach—probably a different section because as soon as we approached, a crowd of French soldiers, with all their equipment, rushed out into the water and climbed on board before we had a chance to turn the boat around to head out to sea. As the tide was falling, we became stuck on the sand. With great difficulty, we persuaded the Frenchman to get out of the boat, and we were then able to turn it round and prevent it broaching—getting broadside onto the sea.

“Through all this time we were so occupied with what we were doing that we were hardly aware of all the other activity going on all around us…. There were aircraft overhead, friend and foe, all the time; continual bombardment of the town, harbor, and of the beaches by the Germans. Ships were being sunk and survivors rescued. All around the town and harbor of Dunkirk fires were blazing, a heavy pall of smoke hanging over it all. From much further off shore, the British ships were bombarding the German positions.

“We eventually left the beaches just before dawn on Saturday, 1st June. I spent most of the return journey in the engine room of our craft trying to get warm and dry. When we reached England again, we had to lie off shore before being taken to Ramsgate by tenders. Everything was very well organized and, seemingly, under control.”

Having retreated from Brussels, Frederick Barker, 4th Division, Royal Engineers, said, “The unwritten rule on Dunkirk Beach seemed to be ‘first come, first served’ as far as evacuation was concerned, and it did nothing to boost our morale knowing we were among the last to arrive. We watched boats arriving, leaving, and occasionally sinking and, with some horror, men making frantic efforts to swim out to the boats, only to drown long before they got anywhere near them, their pathetic water-logged bodies lying face down in the water.”

Arthur Turner, a military policeman, jumped from the mole onto a ship, the Crested Eagle, with his mates and found the ship crowded with wounded men. The ship had gone only a short distance into the Channel when it was bombed. A motor mechanic was on fire. “He was screaming, screaming, and we said, ‘Gor, there’s Freddie Lucas … there’s Freddie!’ We rushed to get a bucket of water and chucked it over him. As we put this bucket down, he was putting his arms in the water, but all his skin came off.

“Then the whole place was on fire. One of our men got a life jacket and pulled Freddie up and fixed the life jacket on him. Me and my mates were holding onto the lattice work where the guide for the wheels was, and everybody was treading on my bloody fingers with big army boots. Then an officer said, ‘Come on lads—let’s swim for it!’ So we dived into the water and started to swim.

“My full pack hit me under the chin as I dived and I smashed a couple of my teeth, but I started to swim and managed to get off my battledress jacket, but I had khaki trousers and braces [suspenders] on and, as I was swimming…. [I] gradually got rid of my trousers, and even my boots. I was a pretty good swimmer, but I tried to touch the bottom and I couldn’t—I just sank. With panic I surfaced and then I swam and swam. Then I managed to stand upright and walk to the shore.”

A Scotsman, Douglas Haig Hodge, and his Royal Artillery unit had evacuated Brussels and were headed for Tournai, where he found the road packed with refugees. German bombers then struck. “When the bombers came down the road, I was lying in a ditch, and it was then that I saw a woman with a little child. What exactly became of them I do not know, but that was the time I began to detest the Germans; I hated the very sound of their name.

“Without our guns, we were now classed as infantry, and I remember reading in the paper at a later date that it was in fact the 9th, our Dundee Battery, which held the line. We were badly mortared outside Dunkirk and took quite a few casualties. Captain Laird, the Battery Commander … marched about like the proper infantry officer in front of his troops. He was a ‘real warrior,’ and on one occasion when I told him I only had one round left, I asked him what I should do. ‘Fix bayonets and charge’ was his unhesitating reply.

“We took quite a bit of mortar fire, but you got to the stage where you didn’t really care what happened next…. Everyone near me was getting wounded except for Captain Laird, who bore a charmed life. I was so blasé about the whole situation that I didn’t realize we were all fighting for our lives.

“We went through some ‘flurries’—flights of aircraft attacking us—to get down to the beach at Dunkirk. We had rifles, and we fired volleys at the planes, which actually stopped them in their tracks. We marched to the beach, and I somehow got separated from the rest. We were taking heavy shelling from the Germans, and when those shells landed—oh, my goodness me, what an explosion!

“We got into groups—30 of us, as I recall—and went down to Dunkirk Harbor. This big hospital ship with red stripes on either side came slowly in, and the nurses were waving to us … That ship saved our lives.” Hodge made it safely back to Britain.

Men in planes were also in great danger. At about 7:50 am on Saturday, June 1, 1940, two Blenheims of No. 254 Squadron and two of No. 248 Squadron took off from RAF Detling to fly a three-hour cover patrol of the Dunkirk evacuation shipping route. They were making their last circuit before returning to Detling and were at 8,000 feet approaching Dunkirk, two miles out to sea and flying parallel to the shore when they were attacked by a swarm of Me-109 aircraft diving on them from the south.

Pilot Officer G.W. Spiers recalled, “I was sitting in the seat on the right-hand side of the pilot. Looking out to my right, I could see the sand beaches with numerous clusters of troops queueing to embark on small craft. As I looked up, I saw Me-109 German aircraft diving in line astern towards our rear starboard quarter. I managed to count 11 109s, and as I looked downwards I saw our other Blenheim, which had been flying in line astern of us, pass beneath to starboard with both engines on fire.”

As soon as Spiers saw the enemy, he yelled to Flying Officer J.W. Baird, the patrol commander, ‘Fighters!’ “We were slowly picking up speed in a shallow dive, but a cold feeling in the small of my back made me realize we were ‘sitting ducks’ for fighters.”

Spiers shouted to Baird to maneuver the aircraft about. “Whether or not he understood I never found out, as the cockpit suddenly filled with … flying fragments as the dashboard and instruments disintegrated in front of me under a series of violent crashes and flashes.

“The smoke started to clear and I looked back through the armor plate to see what had happened to Roskrow, the gunner. The fuselage down to the turret was a mass of bullet holes which were accentuated by the sun beams that shone through the smoke. All I could see of Roskrow was a bloody green flying suit slumped over the gun controls.

“Turning to Baird, I immediately realized he had been hit although he still held the controls. His head was slumped forward on his chest, and blood ran down his right cheek from a wound in the temple that showed through the side of his helmet. Another wound in his neck had covered him with blood, and it had gushed all over my left shoulder. He looked very peaceful with his eyes shut; I was sure he was dead. It was miraculous that I had survived that burst of gunfire into the cockpit.”

Spiers then realized that he would have to crash-land the plane on the water. Spotting an armed trawler some miles off to port, he leaned over Baird’s lifeless body and grabbed the controls. “I pulled back the throttles as the engines were still at full power and were vibrating excessively. Yellow flames from the port engine were beating against the front and side windows and, standing at the side of Baird, I was about to level the aircraft to prevent the vicious sideslip that was causing the flames to play on the cockpit when, suddenly, the windscreen shattered.

“I felt a hot, searing wind on my face [and] felt my cheeks, nose, throat, and mouth shriveling under the heat, but have no recollection of any pain. As soon as the aircraft righted, the cockpit cleared of fire and smoke, and a noticeable peace descended as the cut-back engines purred and the wind gently whined through the shattered glass.

“As the aircraft was now at 5,000 feet, I thought I could glide to the ship without having to open up the engines. As I lost height, the speed of the sea passing beneath magnified alarmingly, and although the thought of using the flaps and lowering the undercarriage to reduce speed occurred to me, I realized that I could not take my eyes off the sea for the impending ditching.

“The trawler was now only a quarter of a mile off and closing fast, and I was only slightly higher than masthead height. I concentrated to keep the wings parallel to the water as I realized the danger of dipping a wing tip. The ripples on the calm sea closed nearer and nearer until there was suddenly a most violent jolt. Although the impact took only a fraction of a second, it seemed like a slow-motion film to me.

“I can still visualise the water bounding in through the nose like a dam which had burst; I remember turning my back to the barrage and gently cushioning on it. The silent cockpit was now full of blood-colored sea, and I struggled to reach the normal entry sliding hatch above Baird’s head.

“As I held my breath, many of those past happinesses which had occurred during my life passed through my mind as I realized I would not escape. I had never prayed to God with such agony or earnestness. I tried to suck water into my lungs to hasten the end, but I was unsuccessful and only swallowed it. My lungs were bursting, and my pulse pounded in my ear drums, brilliant flashes and yellow spots appeared in front of my eyes; I thought of the sea bed—its creatures and crabs.”

Suddenly Spiers realized that there was no floor under him, so he made his way out of the sinking aircraft, swimming to the surface and emerging “about five yards away from the starboard side of the aircraft. To my surprise, it was not lying horizontal below the surface of the water but the stub end of the fuselage was pointing upwards at 80 degrees with a jagged scar from which the turret and tail had been torn off. The steep angle was the reason why I could not reach the normal exit hatch.

“I think that I had been trapped inside the fuselage for over three minutes. My parachute floated in front of me, and this I quickly discarded. My burned face now started to sting, and I carefully abandoned my flying helmet.”

During this time, Spiers could see the trawler steaming toward him. He inflated his Mae West life preserver and started to swim away toward the ship. The seamen stretched out a pole, passed it down to Spiers, and pulled him aboard. After dodging an attack by German aircraft, the trawler made contact with a tugboat, which delivered Spiers to Ramsgate, on the northeast corner of the Dover peninsula.

Arthur Davey and his unit, the 7th Military Ambulance Company, had been ordered back to Dunkirk from their location in southwest Holland—45 miles away. During the drive, the drivers constantly scanned the skies at the German warplanes that circled above. Everywhere, it seemed, towns and villages were on fire from the bombings, and the road was badly cratered. Davey’s unit took to the back roads to avoid the traffic jams and lines of refugees that were clogging the main roads.

After darkness fell, the German pilots dropped parachute flares to illuminate the landscape. “Every moment we thought that they would spot our vehicles, and the tension was unbearable,” said Davey.

The next dawn, Davey recalled, “We could see shell-bursts in the sky, heard AA gunfire, and realized that our dream of a secure haven [at Dunkirk] was entirely false. A huge cloud, dense black, hung over the town and sea, swirling and eddying, the smoke from the huge oil storage drums on the quayside, bombed a day previously. Soon we could see and hear the roaring flames, too, and the nightmare welcomed us.”

The quayside itself was crowded and in chaos. The ship that was supposed to take the ambulance company to England was not due in until the following day. Dive bombers swooped in, strafing and bombing everything.

When Davey’s unit reached the quay late in the day, it was a scene he never forgot. Everywhere there were ambulances, hundreds of them, all waiting their turn to unload their wounded passengers onto a ship that was standing by. The wait was agonizing, as everyone expected to be attacked at any moment.

That evening, the Luftwaffe came over and plastered the town again. Orders came down for Davey and the 7th MAC to head for a park three miles west of town and spend the night under the trees. The next day Davey noted that the oil tanks were still blazing away and black smoke covered the waterfront; half of Dunkirk, too, appeared to be ablaze. Trying to make their patients as comfortable as possible, the ambulance drivers gave them tea and some food while they waited nervously for another aerial attack.

Late that day the 7th MAC was ordered to return to the quay, although the air raids were increasing in ferocity. A hospital ship was expected to arrive, and the Royal Air Force was to provide protection while the wounded soldiers were transferred from shore to ship.

Davey recalled, “Jerry was systematically ‘blitzing’ Dunkirk, and not missing much. Along the canal bank, soldiers were marching, dirty, bandaged, worn-looking in single file towards the docks, and we realized this was no strategic retirement but a decided withdrawal from northern France and Belgium.

“We drove through the shambles that was a town but a few days before. The roads were strewn with debris, rocks, masonry, girders; full of craters, here a dead horse, there an overturned ambulance, a couple of lorries blazing away fiercely.” Everywhere houses were on fire, with firemen vainly trying to stanch the flames.

Finally reaching the quayside, the 7th MAC learned that the hospital ship would not arrive for another few hours; meanwhile, 30 German planes dived onto the scene, sending Davey and everyone else scrambling for shelter. There was no sign of the RAF, and Davey said, “The promised air protection was merely a ‘nerve tonic.’”

There was little protection to be had on the ground, so the British—both the walking wounded and the sound, such as Davey—sprinted for the dock and leaped into whatever boat, dinghy, or steamer was close by. Davey said, “It seemed safer on the boats somehow, while bullets and shrapnel rained on the decks and quayside, and the earth and sea alike vibrated with the concussion of the bombs.

“The planes were dive-bombing and the scream of their engines, then the whistle of their bombs, would be followed by the noise of the anti-aircraft guns.” As quickly as it had begun, the raid was over. Ten minutes later, a new raid took place, and the whole mad event repeated itself.

At about 8:30 pm, a British destroyer appeared and began peppering the sky with AA fire in hopes of driving off the Luftwaffe. The AA fire heartened the men on the beach and dock, and the transfer of the wounded recommenced. “The neatest, swiftest handling of stretchers that I have seen followed,” Davies said. The ship made it safely back to Dover.

Ron Bouverat was a lance corporal in the 48th Division when his unit fell back to Dunkirk. He was driving a lorry full of rations and recalled, “The road on either side of us was littered, of course, with abandoned vehicles and things upside down…. I wandered around the beach, and it was like Blackpool on a bank holiday. That was at Bray-Dunes; it wasn’t actually at Dunkirk.

“I looked around and saw a Messerschmitt coming down, machine gunning, so I did the 100 yards very fast into the sand hills and got a large sand hill in between myself and the Messerschmitt, which seemed sensible. People were scattering all over the place.” The next morning he saw “a paddle boat—no, a big ferry—and the Germans had dropped a bomb down the funnel and it was on fire; it was beached.”

Later, Bouverat and a few other BEF men found a bullet-riddled lifeboat on the beach and decided to take their chances in it. Pushing it into the water, they rowed out to a British ship that was about to depart the scene; everyone in the little boat was saved and taken back to Dover.

Stan Rowley, a member of the 1st/9th Manchester Regiment, had been wounded in the leg when the Germans invaded France and was being taken to Dunkirk for evacuation. He said, “The field ambulance was full of the wounded (really bad wounded). It took us 50 miles to Dunkirk. It took all night (about 12 hours). We went straight to the beach by a wall (on the beach were the wounded). This Major (from Manchester) kept giving us hot sweet tea. Not many bombers got through to shoot at us—the RAF did a wonderful job.

“A bomber that did get through killed my mates that I went to school with and went to the pictures with. It was a pleasure steamer that they were on—I think it was the Gracie Fields. There were a lot from Manchester on the ship that was bombed.

“On the third night we were to be taken to the mole. They were trying to get a hospital ship in. They took us on the mole (loads of wounded), and four of us were lying inside a wall of cotton bales for protection from the shelling. We looked round the corner of the cotton to see little dots of ships. The white one was the hospital ship (the Newhaven) being escorted by about 10 destroyers. Jerries were flying over causing pandemonium!

“We could see the ship coming in, and then, when it got to the mole, it turned around and moved away. We thought it was going because of the shelling. There was an uproar of men shouting. Anyway, he backed up (the boat used to be a ferry), and he moved back to the mole very quickly.

“Boards were put down, and people walked onto the boat. I crawled on because I couldn’t walk. I got on my backside and slid down about a dozen stairs onto the boat. At the bottom of the stairs two blokes were stacking you to clear the entrance to the boat.

“Stretchers were put on board and 200 wounded were taken back. We arrived at Newhaven, then went on a train to Hendon, and we got sandwiches and a cup of tea … at Hendon. Civilians arrived at the station with gifts of food and cigarettes—I could have opened a shop with the cigarettes!”

Another of the wounded men at Dunkirk was Albert George Heath of 361 (5th London) Battery, 91 (4th London) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery. He had been seriously wounded near Lille on May 21, necessitating the amputation of his right leg.

“I eventually arrived at Dunkirk,” he said. “Whilst in the ambulance on the quayside, a bomb exploded nearby. Shrapnel ripped into the ambulance, severing my right arm, and the ambulance then caught fire! French sailors pulled me from the burning ambulance, but I suffered burns to my head and face. As I was embarked onto the SS Canterbury, another bomb exploded in the water beside the boat, which pitched, and I ended up in the harbor. This time the crew pulled me out!”

Heath’s son later said, “During the next five years, Dad underwent 31 major operations on both his arm and leg. Until his death in 1985 at the age of 75, Dad must, at times, have been in terrible pain from these injuries, but he never let the real pain show. He worked up to retirement at 65 and led as active a life as his disability would allow. He was a very brave man.”

James Bradley reflected back on that time: “Dunkirk changed my character completely. It changed my thinking about soldiering and actually about killing—accepting it as a part of your day, which you would never do otherwise. You fight back the fear, you put a lid on it—it’s a way of life that takes over because you want to survive. The feeling for survival is a wonderful thing.”

During the nine days of evacuation, more than 338,226 British and French troops were evacuated to Britain, where they would have to begin building a new army from scratch.

These are just a few of the over 200 Dunkirk stories. To read more, go to http://www. bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar