By Christopher Miskimon

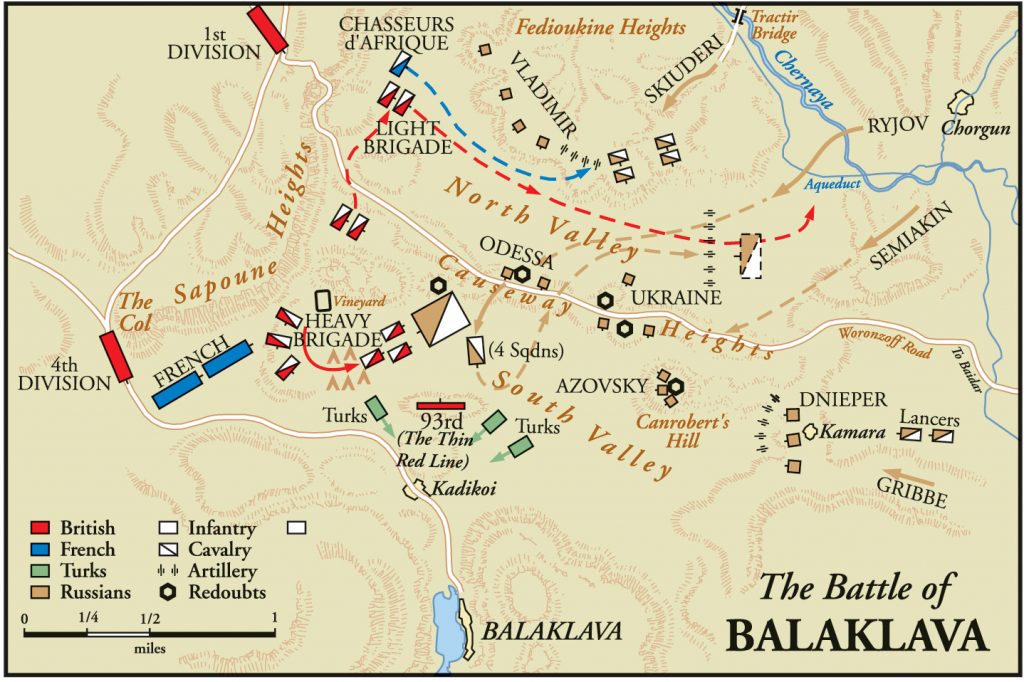

Six battalions of Russian infantry, 30 cannons, and a cavalry force deployed in the North Valley east of Sevastopol near the town of Balaclava. They occupied three sides of the valley, looking down on it. The other end was in the hands of the British Army. Spread across the valley floor were thin lines of horsemen belonging to Great Britain’s Light Brigade. The 674 men and officers looked resplendent in their blue and red uniforms, trimmed in gold around the chest and shoulders. They clutched their lances and swords and eyed in the distance the Russian guns that they were ordered to capture.

At their head sat Maj. Gen. James Brudenell, Lord Cardigan, an English nobleman with a reputation as a bad-tempered, impulsive man. He took position in front of his brigade. Despite his faults, he did not lack courage. Without a trumpet call, he urged his horse forward and the brigade followed at a trot. Some distance behind and to their right, the Heavy Brigade trailed them. It was a spectacle as foolhardy and pointless as it was courageous and heroic. The Charge of the Light Brigade would go down in history and verse, but the ill-fated attack was only one act of bravery and determination that would occur on the morning of October 25, 1854.

The Crimean War see-sawed back and forth in its first year. The Turks held their own on land, but in November 1853 a squadron of Russian warships destroyed a Turkish squadron at Sinope in northern Anatolia. Two months later an Anglo-French naval force entered the Black Sea. On March 28, 1854, the European powers declared war on Russia. Britain and France decided to attack the Russian base at Sevastopol, on the southern coast of the Crimea. The stronghold was Russia’s principal naval base in the Black Sea. Its capture or destruction would cripple Russia’s ability to continue the war.

The Allies assembled an army of 50,000 troops and landed unopposed on September 13 at Calamita Bay. The landing force advanced toward Sevastopol, and a sharp clash occurred at Alma on September 20. Although the Allies won the battle, they failed to press their advantage. The result was that the Russians were able to regroup. They retreated to the safety of the Sevastopol fortress to await the inevitable Allied siege.

The Allies marched around Sevastopol and secured several small harbors capable of handling their logistical needs. The British occupied Balaclava, which had a long narrow inlet. By possessing Balaclava, the British ensured that they could easily receive supplies by sea given that the siege lines were only seven miles from the harbor.

General Prince Alexander Menshikov, the Russian commander in chief, plotted a counterattack to the exploit vulnerability in the British lines. He believed it was possible for a Russian force to sever the Allies’ thin line of communication to the port. At the very least, an attack would force the English to divert forces, thus weakening the Allied right flank surrounding Sevastopol. He assigned Lt. Gen. Pavel Liprandi to lead the attack. Liprandi’s 12th Infantry Division had just arrived from the Danubian front. Liprandi had 25,000 infantry, 3,400 cavalry, and 78 cannons. This was more than enough to capture the port if the Russians moved quickly and forcibly without hesitation.

The British forces deployed around Balaclava contained some of England’s best troops but, tragically, also some of its poorest commanders. At the time of the Crimean War officers gained their commands through the purchase system; that is, wealthy noblemen bought a position within a particular regiment. Moreover, they also paid for promotions. Membership in many regiments incurred great expenses for uniforms and the officer’s mess. This limited commissions for the most part to wealthy aristocrats. Many of these high-born individuals considered themselves superior by dint of birth. Unfortunately for their troops, they had little or no interest in learning their craft.

Men of lesser means often took positions in the Indian Army, a less expensive proposition; however, due to their lower status and wealth they were generally snubbed as inferior by officers of home units. This social divide meant Indian officers, often more experienced and competent than their England-based brethren were kept from positions where they could be effective. Despite the purchase system’s flaws, most regiments had a core of solid officers.

The real weakness of the British Army during the Crimea War was in its top leadership. General FitzRoy Somerset, First Baron Raglan, was the commander in chief of the British forces. He had served on the Duke of Wellington’s staff during the Napoleonic Wars. He was selected to lead the British forces during the Crimean War largely because of his association with Wellington. Yet he had never led troops in battle, nor did he command the respect of his subordinates.

The British expeditionary force contained five infantry divisions, four led by sexagenarians, and one led by Queen Victoria’s 35-year-old cousin, Prince George, Second Duke of Cambridge. Many brigade commanders and staff officers also were elderly. As for the rank and file, they were steadfast, loyal, and brave. The most famous unit at Balaclava was the Cavalry Division, commanded by the ill-tempered Lt. Gen. George Bingham, Third Earl of Lucan. Considered a martinet, Lucan’s first command was the 17th Lancers, which he had purchased for 25,000 pounds when he was 26. Unlike Raglan, he had campaign experience. Lucan had served with the Russians during the Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829. His command of the Lancers was marked by constant drill, smart uniforms provided at his own expense, and draconian discipline.

The Cavalry Division was divided into two brigades. Brig. Gen. James Scarlett led the Heavy Brigade, and Brig. Gen. James Brudenell, Seventh Earl of Cardigan, led the Light Brigade. Scarlett was a capable man who had the respect of his troops. He had never seen combat, but he had the wisdom to acquire the services of a few veteran British officers who had served in India to assist him. The brigade’s five regiments used larger, heavier horses and carried carbines in addition to swords. They were intended as shock troops, which if used properly could punch a hole in an enemy line.

The British typically employed the horsemen of the Light Brigade as scouts. Armed with lances and swords, they could move quickly around a battlefield on their smaller, lighter mounts. Like the Heavy Brigade, the Light Brigade also contained five regiments. Cardigan, who was irascible and overbearing, had been removed from his first command in 1832 for incompetence; nevertheless, his wealth and influence allowed him to return to active service.

Cardigan was Lucan’s brother-in-law. The two men did not get along, and Cardigan often acted as if his brigade was a separate command. They argued constantly and were frequently observed bickering over matters normally handled by sergeants.

The system of orders used by British commanders to direct units in action was simple; however, it was vulnerable to missteps and confusion. Commanders could often see the entire battlefield and would give orders to a chief of staff who recorded them. An aide-de-camp would carry the orders to the relevant subordinate. Sometimes verbal orders would accompany written ones, which the aide-de-camp also relayed. By the rules of the time, verbal orders allowed for latitude by the lower commander while written ones were adhered to exactly and immediately. If the aide-de-camp was able to clearly and accurately relay orders, the system worked; if not, there was the risk of disaster.

Raglan had realized the potential threat to his supply line and had taken steps to address it. He had deployed troops in various strongpoints to protect the road that led from the harbor north through the village of Kadikoi to Sapoune Heights. Beyond Kadikoi to the northeast was a plain that sprawled to the distant Fediukhin Heights. To the south of the Fedioukine Hills lay Causeway Heights, which divided the low ground into the North Valley and the South Valley.

Raglan’s troops had hastily dug six redoubts to guard against attack. Redoubt 1 was situated at the eastern end of the ridge on Canrobert’s Hill, which was named for a French commander. The rest were situated at half-mile intervals to the west. Redoubt 1 was manned by a battalion of Turkish troops and contained three 9-pounder naval guns.

The Turkish troops were colonial Tunisians who the Ottoman army had pressed into service with the Allies. They were raw troops who lacked formal training. Worse yet, they had not received rations that comported with their Muslim diet, and therefore they were sorely famished. Redoubts 2, 3, and 4 were manned by a half battalion of these Turkish troops and a pair of guns. Redoubts 5 and 6 had not yet been built. Each of the four manned redoubts had a British artillery noncommissioned officer overseeing the gun crews.

The Cavalry Division’s encampments were located at the far west end of Causeway Heights. Lucan dispatched patrols from that location to monitor the Russians on the high ground north of the Chernaya River.

Raglan intended the redoubts as tripwires. If the Russians launched an attack toward Balaclava, he expected them to delay the enemy until reinforcements arrived from the main siege lines. In addition to the Turks in the redoubts, he also stationed the 93rd Highland Infantry Brigade, which was commanded by Maj. Gen. Sir Colin Campbell, just north of Kadikoi. Raglan had entrusted Campbell with the overall defense of the strategic port. The Highlanders were supported by a battery of artillery. In addition, a force of 1,000 Royal Marines was stationed a mile behind the Highlanders. Altogether, the British had approximately 5,000 troops in place to delay a Russian thrust toward Balaclava until reinforcements arrived.

Rustum Pasha, the commander of the Turks, learned from a spy on October 23 that the Russians planned to attack the following morning. He relayed the information to Lucan and Campbell, who in turn informed Raglan. But Raglan was loathe to take action because he had sent 1,000 men to Balaclava three days earlier in what proved to be a false alarm. So when he received the information, he instructed his subordinates to keep him apprised of the situation.

Lucan rode out to inspect his vedettes deployed in South Valley at dawn on the day of the expected attack. Accompanying him was Colonel Lord George Paget, who was in temporary command of the Light Brigade given that Cardigan routinely slept on Raglan’s luxury yacht Dryadanchored off Balaclava.

At sunrise the party observed a pair of flags flying above Redoubt 1. Only one of Lucan’s staff remembered that this was the signal for a general advance by the enemy. Just moments later the guns of the redoubt fired, thereby removing any doubt of the situation.

As the distant guns thundered, one of the vedettes arrived and reported three Russian divisions crossing the Chernaya River beyond the distant Fedioukine Hills. One division ascended the hills, another was moving toward Causeway Heights, and yet another was in the process of attacking Redoubt 1. The Russian general hoped he could advance quickly enough to take the British flank before reinforcements arrived. He expected the advance to take three hours. If the Russians could capture Balaclava beforehand, it would threaten the entire siege.

The Allies responded quickly. Raglan ordered his 1st and 4th Divisions to move onto the plain. The Duke of Cambridge, who commanded the 1st Division, complied immediately, but it took him 30 minutes to get his troops moving. Maj. Gen. Sir George Cathcart, who commanded the 4th Division, took longer to get his troops in motion. He grumbled that his men had just returned from trench duty. The aide-de-camp, who was aware of the seriousness of the situation, persisted and Cathcart ultimately obeyed even though it took him a full hour to get his division marching. The French sent Maj. Gen. Pierre Bosquet with two infantry brigades and two regiments of Chasseurs D’Afrique, which were elite light cavalry, to assist the British.

While British infantry moved slowly toward the sound of battle, the Russians stormed Redoubt 1 at 6 am. The five battalions of Russian infantry participating in the attack were supported by 30 guns. To their credit, the 500 Turks manning the redoubt held on until 7:30 am. They significantly delayed the Russians at the cost of 170 of their men. Many of their casualties were essentially executions by the Russians once they had breached the defenses. The British artillery NCO escaped after spiking the guns.

British infantry and cavalry stationed nearby made no move to assist the Turks and only one British battery opened fire on the Russians attacking the redoubt. The Turkish troops in the remaining three redoubts watched eight Russian infantry battalions advancing. The advancing Russian infantry were supported by artillery and cavalry, including the dreaded Cossacks.

Upon observing the retreat of the Turks from Redoubt 1, the Turks manning the other redoubts immediately fled their positions. The Russian guns had a greater range than the British guns, and the British batteries withdrew to prevent their destruction. As the Turks fled, screaming Cossacks chased after them and gored some of them with their lances. Although some of the Turks fell in beside the Highlanders, others ran for the port in a state of pure panic shouting “Ship! Ship!” The NCOs in the other three redoubts also spiked their guns before retreating.

The French arrived on Sapoune Heights shortly after 8 am and unlimbered their guns. Raglan also arrived with his staff and established a superb observation post 500 feet above the plain from which to observe the battlefield. Raglan watched as the Russians unlimbered their guns on the eastern slope of Causeway Heights. At the east entrance to the North Valley, Russian horse soldiers advanced at the head of 20 guns and additional infantry.

The British Cavalry Division was deployed on Raglan’s right. The Cavalry Division prepared to strike the flank of the advancing Russians, but Raglan believed they were too isolated to successfully carry out their planned attack. He therefore sent orders to Lucan instructing him to “take ground to left of second line of redoubts occupied by Turks.”

Lucan was confused by this order as he saw only the one line of redoubts running along the Causeway Heights. By that point, the Turks had fled and the redoubts were unmanned. Raglan’s aide-de-camp explained the order meant for Lucan to move his cavalry to the western end of the heights so that the horse soldiers could be covered by the French artillery. Lucan reluctantly complied, fearing the move would be seen as cowardly. While Lucan was prevaricating, Cardigan arrived on the field.

Four squadrons of Russian cavalry ascended Causeway Heights. Observing the move, Raglan realized the Russians’ objective was Balaclava. Because of this, he needed to reposition his cavalry. “Eight Squadrons of Heavy Dragoons to be detached towards Balaclava to support the Turks, who are wavering,” he ordered. The order made sense, except that it was the unwavering 93rd Highlanders they were to support. It took 30 minutes for the aide-de-camp to reach Lucan with the order.

The Russian cavalry descended from Causeway Heights into South Valley and advanced toward the 93rd Highlanders. Campbell ordered his men to lie down on the reverse slope to avoid incoming artillery fire. Either the Russians did not see them or they underestimated the brigade’s numbers. Five hundred men defended the knoll. When the Russian cavalry was 900 yards away Campbell ordered his men forward. Believing the small force of Russian cavalry advancing against him to be little threat to his veteran troops, Campbell decided to forego deploying them in a square. He felt that the awesome power of his riflemen firing the Minie ball was sufficient to stop the Russian cavalry. He therefore deployed his men in a thin line two deep.

Lieutenant General Ivan Ryzhov’s 500 cavalry in blue and light grey uniforms charged the Highlanders. Moments before Campbell had spoken firmly to his soldiers. “Remember men, there is no retreat from here,” he said. “You must die where you stand!” The cocky soldiers laughed heartily and then broke into a loud cheer. They were eager for the confrontation.

Lucan watched from the escarpment as the Russian cavalry charged the brave Scots. At 600 yards the Scots fired a rolling volley that inflicted little damage but bought time for them to reload. British guns behind them opened in support. Cannonballs opened gaps in their line, but the Russian horsemen dressed ranks and continued forward. When the enemy was 350 yards away, the Scotsmen fired a second volley. The Scots were surprised that the Russians wheeled left even though the volley felled only a small number of horsemen.

The Scottish troops wanted desperately to charge down the knoll and attack the apparently fleeing horsemen, but Campbell would not allow it. It was a sound decision because the Russians were trying to outflank the Highlanders. Campbell quickly sent his grenadier company to engage them. The grenadiers rushed down the slope and fired a third volley into the Russian horsemen, toppling a few more from their saddles. The Russians, having decided they had lost enough men, galloped back to their lines.

The Russians’ precipitous retreat puzzled the Scots because it did not seem to them as if they had inflicted enough losses to repulse the charge. They later learned that the last two volleys inflicted more casualties than was apparent. Many of the wounded Russians clung to their saddles afraid to fall on the field and risk capture or death. The spirited Scots had held their ground. They were “a thin red streak tipped with a line of steel,” wrote eyewitness William Russell, special correspondent for The Times of London.His description later was incorrectly reproduced as “Thin Red Line.”

The rolling terrain handicapped both sides equally. Raglan could see enemy formations moving about from his elevated position and send orders to subordinates to counter them; however, his subordinates positioned on lower ground often could not see their opponent’s movements. This caused them to doubt the orders they received. The officers of the Cavalry Division in particular became deeply frustrated.

When he received his orders, Lucan instructed Scarlett to lead his Heavy Brigade toward Kadikoi to support the 93rd Highlanders. He gave specific orders to Cardigan to maintain his position as instructed by Raglan; however, he added that he was to attack “anything and everything that shall come within reach of you, but you will be careful of columns or squares of infantry.”

After giving these orders Lucan rode onto Causeway Heights with his staff. They arrived in time to see the Russian cavalry attacking the 93rd Highlanders to their right. To their left, the main body of the Russian force was walking up the opposite side of the ridge directly toward the flank of the Heavy Brigade. Lucan’s aides rode to warn the British horsemen, but Scarlett already had spotted the Russians on the crest of the heights with the steel tips of their lances gleaming in the morning sun. He ordered his men to wheel left. They formed into squadrons for battle.

Watching the mass of Russians moving over the heights, Scarlett ordered his command to the right to avoid the abandoned camp and a local vineyard. He wanted room for his cavalry to maneuver. Ryzhov observed the same obstacles and shifted his command to the left so that the opposing sides faced each other. Scarlett pulled the three squadrons nearest him into a more compact formation to increase their shock effect, but before they could complete that movement, the Russians struck. With a sound of trumpets 3,000 horses and riders thundered down the slope toward the much smaller British formation. A few moments later a second trumpet call brought them to a halt, with the outer edges of the formation slightly forward. The British were only 400 yards away. British officers dressed the ranks of their squadrons as though oblivious to the enemy. A few Russian cavalrymen took potshots at the British, but otherwise there was a lull in the action.

Scarlett was pleased with his lines. He positioned himself in front of them. Standing with him was aide-de-camp Alexander Elliott, Trumpet Major Thomas Monks, and orderly Sergeant James Shegog. Scarlett ordered Monks to sound the charge. Three squadrons of British cavalry slowly started forward up the gentle slope toward the waiting Russians, who likewise advanced. Scarlett wore a dragoon’s helmet, while Elliott wore the cocked hat of an English officer. Because of this, the Russians mistook Scarlett’s aide for the commander and one Russian officer charged toward him.

The two masses collided. Elliott dodged the assault by the Russian officer and buried his own sword to the hilt in his attacker. The mortally wounded Russian was knocked from his horse. Just behind him Scarlett lashed about with his own blade, fending off numerous attacks. Sergeant Shegog stayed with Scarlett, deflecting attacks aimed at his commander while dealing deadly blows in return. The rest of the brigade hit the Russians with shouts and cheers.

Since the charge was uphill and the Russians were barely moving again, their closing speed was only about eight miles per hour. When the second British line crashed into the Russians, it pierced their formation to a depth of five files. The fighting quickly became a frenzied melee. The two sides were so tightly packed that some of the slain remained upright in the saddle. The British riders quickly discovered Russian greatcoats were excellent protection against the slashing of their sabers; for that reason, they began aiming for the heads of their foe. Some even grabbed Russians by the throat and dragged them from their horses to be trampled under hoof. The Russian lancers found themselves at a decisive disadvantage because they lacked room to use their weapons effectively.

Still, the Russians resisted hard, even against the superior swordsmanship and aggressiveness of the British, many of whom survived due to the bluntness of the Russian blades. The outer ends of the Russian line began to curve inward and it appeared the smaller British formation, which was deeply mixed with the Russian center, might be surrounded and overwhelmed. A squadron of the dragoons crashed into the Russians’ curving left wing. Meanwhile, another aide brought forward the 4th Dragoon Guard, which slammed into the Russian right wing. They were followed closely by the Royals, who rode into the rest of the right wing.

The effect on the Russian force was jarring. Receiving so many hammer blows from different directions shattered their morale. The left rear of the formation turned and fled. Within moments the rest of the Russian horsemen wheeled about and rode for their lives. A few dragoons pursued but soon British trumpeters sounded the rally. Officers raised their swords and their troopers sought them out. Within a short time the regiments reformed. The entire action lasted only five minutes. The British suffered 78 casualties compared to at least 200 for the Russians.

While the Heavy Brigade rode to glory, 500 yards away the men of the Light Brigade waited and watched. Cardigan sat at their head but gave no orders to support the other brigade. One of his regimental commanders almost led his unit alone to the fight, but Cardigan ordered him to stay put, stating their last orders were to remain in place. Actually, Lucan had sent a trumpeter toward the Light Brigade to sound the charge, but the unit had not budged. Lucan then sent a note to Cardigan reminding him it was his duty to attack the enemy in the flank when his divisional commander was engaged to the front. Cardigan’s reasoning remains a mystery to this day.

By10:30 am the battle was decided. The defeat of the Russian cavalry meant Liprandi lacked a screen for his advance across the South Valley. He decided to withdraw back to the eastern end of the North Valley, where his guns had moved to provide cover. The cavalry fell back in order to reform, and the infantry stood idly by. A small Russian force still held the Causeway Heights, but it began to withdraw when British infantry appeared. It did so after blowing up the magazines of Redoubts 3 and 4.

But Raglan was not finished fighting. He did not want the British guns captured in the redoubts to be taken away by the Russians. In his mind, this was tangible proof of Russian victory. He wanted those guns retaken. His intent was for two infantry divisions to advance along the South Valley and Causeway Heights while the cavalry screened them. He quickly composed his third order to Lucan. “Cavalry to advance and take advantage of any opportunity to recover the heights,” he instructed. “They will be supported by the infantry which have been ordered to advance on two fronts.”

It made no sense to Lucan. Which heights did Raglan mean? Where was the infantry? Which two fronts were they to advance on? The aide-de-camp could offer no explanation, so Lucan decided to wait until the infantry arrived and moved his cavalry to the western end of the North Valley since the South Valley was empty of Russians. From his elevated position, though, Raglan could see Russian artillerymen readying their limbers. They were actually preparing to withdraw their own guns, but Raglan feared they would take the captured British guns. He then wrote his fourth order admonishing Lucan to advance rapidly to prevent the Russians from withdrawing the captured British guns. The order informed Lucan that the French cavalry was on his left in a position to support him.

Raglan instructed Captain Lewis Nolan to deliver the order even though Nolan disliked Lucan and Cardigan. Nevertheless, he was regarded as the best horseman in the army. Raglan knew he would be sure to deliver the order. Nolan exited at a gallop along a narrow trail and soon found Lucan. Since the latest order made little more sense than the previous one, Lucan asked for more information. Showing his disgust, Nolan informed him that he was to attack immediately.

“Attack? Attack what? What guns?” Lucan asked angrily. Nolan angrily waved his arm in the direction of the far end of the North Valley. “There, my Lord, is your enemy! There are your guns!” replied Nolan. His actions and statements were insubordinate, but rather than arrest Nolan, Lucan looked across the valley and the task he thought assigned to him. Nolan also insulted Cardigan, who promised to have him court-martialed, that is, if they lived.

Russian guns lined Fedioukine Heights to the left. More Russian guns were deployed on Causeway Heights to the right. Straight ahead lay more guns. These were the ones that he was supposed to attack. Enemy infantry also massed nearby along with the reformed Russian cavalry behind the guns. It seemed mad to charge down the valley where fire would assail them from three directions. Rather than demand clarification, Lucan ordered the Light Brigade to advance with the Heavy Brigade in echelon to its right rear.

The Light Brigade formed into three lines for the charge. The first contained the 13th Light Dragoons and 17th Lancers. Behind were the 11th Hussars in the second line, and the third contained the 8th Hussars and 4th Light Dragoons. Cardigan took position in front at 11:10 am. “The Brigade will advance,” he shouted. “First squadron of the 17th Lancers direct!” He set off at a walk followed by the brigade, which soon increased its pace to a trot. Participants in the charge later recalled being deathly afraid of letting down their fellows. Discipline held, and the brigade stayed coherent and focused.

Nolan chose to ride with the Light Brigade and took a position with the 17th Lancers. After the formation covered about 200 yards, he took off diagonally across the brigade’s front, shouting and waving his sword toward Causeway Heights. It is believed he realized the brigade was off course, and that Raglan had intended them to scale the heights toward Redoubt 3. This was the closest fort containing captured British guns. Nolan may have been trying to direct them toward their assigned objective, which he failed to do earlier.

Before Nolan could make his intent clear, though, a Russian shell exploded nearby, sending a shard of metal into his chest. His sword fell from his hand, his arm still raised. A moment later he slipped lifelessly from his mount, which fled back through the ranks of the Lancers.

The brigade rode past Nolan’s body just before receiving the command to draw swords. They did so with a cheer and moved forward through a storm of shell and shot. Each time a rider was brought down, those remaining closed ranks toward the center. Cardigan kept them in tight formation. The Light Brigade, mounted on smaller, faster steeds drew ahead of the Heavy Brigade, now far behind and to the right. Like their brethren in the Light Brigade, they were taking artillery fire. Within a short time the heavy cavalrymen suffered more casualties than they had in the South Valley just minutes before.

Lucan accompanied the Heavy Brigade. When he looked left he could see the trail of broken men and horses left behind the Light Brigade as it charged. “They have sacrificed the Light Brigade!” he said to his adjutant. “They shall not have the Heavy if I can help it!” With that he ordered the brigade to halt. The trumpeter sounded the call and the Heavy Brigade slowed to a halt before wheeling away out of cannon range.

On the Sapoune Escarpment British and French officers watched in horror as they realized the tragic mistake unfolding below. Some wept. “My God, what are they doing?” cried one French officer. “I am old, I have seen many battles, but this is too much!” Bosquet was horrified. “It is magnificent, but it is not war,” he said. Determined to help, he ordered the 4th Chasseurs d’Afrique to assault the Fedioukine Heights and take the Russian guns there. He knew the survivors of the charge would return down the same killing ground in the valley and hoped to improve their chances.

The Light Brigade came within range of the Russian infantry and their cohesion slipped. The formation opened up as horses went to a gallop. Corporal James Nunnerley of the 17th Lancers saw the headless body of a sergeant still in the saddle, gripping his reins with his lance pointed straight ahead. His horse went another 30 yards before the corpse slid off the mount. His surviving comrades raced ahead. The Russian gunners rammed double charges into their cannons. When the Light Brigade was 50 yards away they let loose a stunning volley. Flames lit from the muzzles, sending clouds of powder smoke into the air as a hail of metal tore into the British horsemen. Almost the entire front rank of the brigade went down. Nunnerley’s horse was hit in a leg, felling him as well.

It was a terrible moment of carnage and violence, but then the cavalry was upon the Russian batteries. Within seconds they cut down most of the gunners in a furious storm of sword and lance. Behind the first line the 4th Light Dragoons and 11th Hussars charged into the left and center of the Russian position and slaughtered the remaining cannoneers. “The flame, the smoke, the roar were in our faces,” wrote Corporal Thomas Morley of the 17th Lancers, who said it was like “riding into the mouth of a volcano.”

Russian infantry stationed nearby were shocked by the ferocity of the attack and formed a square for defense. The British cavalry instead made for their Russian counterparts, who were still affected by their earlier defeat. The Russian riders broke and fled eastward for the Chernaya River. They did not stop until they were in sight of it. Meanwhile, the 8th Hussars stopped near the defeated battery and created a rallying point for the brigade.

Cardigan became separated from his troops and was surrounded by Cossacks. He was saved by nearby Russian Prince Radziwill, who actually knew Cardigan before the war. The prince offered a reward for Cardigan’s capture, so the Cossacks contented themselves with jabbing at the Englishman with their lances. Moments later he was saved by the arrival of some of his troopers, who helped him escape. Afterward he shamed himself forever by riding away without even trying to rally his men and lead them back. Instead, his second in command, Lord Paget, and the surviving officers and noncommissioned officers gathered those remaining and began withdrawing back down the valley.

Russian cavalry behind them had rallied and now made weak attempts to counterattack. Liprandi sent a regiment of lancers down into the valley from the Fedioukine Heights to block their retreat. This forced the survivors, many of whom were on foot, to move closer to Causeway Heights, where they endured more artillery fire. Cannon fire cut down more men while Russian lancers ran through others. Those in groups were able to force their way out from the enemy cavalry, but most of the stragglers were lost. The only respite was that the French cavalry managed to drive off some of the Russian guns, reducing the fire.

As each party of survivors returned, the Heavy Brigade cheered them. Cardigan acknowledged the cheers while Paget and his officers openly sneered at him. Only 195 men answered the roll call. Paget later wrote a formal letter complaining about Cardigan’s conduct and resigned his commission. Back in the valley, 40 men were taken prisoner by Cossacks, who beat and dragged them before turning them over to the Russians. When Liprandi asked how much alcohol they had been given to make such a charge, Private William Kirk of the 17th Lancers said their officers had not given them any. “By God, if we had so much as smelt the barrel we would have taken half Russia by this time!” he said.

Raglan made no further moves, abandoning the plan to advance along Causeway Heights. The Russians eventually withdrew at dusk, ending the battle. Lucan was held responsible for the costly attack, but his career did not suffer. Indeed, he was eventually promoted to the rank of field marshal. Raglan died of cholera the following June. As for Cardigan, he was exonerated as having followed orders and returned home to a hero’s welcome. But when stories later came out describing how he abandoned his men, his reputation did suffer. All shared the blame for the Light Brigade’s heavy losses. The glaring defects of the British army during the Crimean War eventually led to reforms that improved the military branch.

The Russians, who needed a morale boost after the defeat at Alma, celebrated the battle as a victory even though they had not even come close to capturing Balaclava. Their timidity in the battle probably stemmed from their fear of the firepower of the British infantry. Liprandi’s troops paraded through Sevastopol with the captured British guns and other trophies gathered up from the battlefield. Their limited success at Balaclava encouraged them sufficiently to launch a probing attack against the British position atop Mount Inkerman outside Sevastopol the following day.

Despite the heavy losses in life suffered by the Light Brigade, their bold and brash attack had unnerved the Russian cavalry supporting the guns they attacked. When viewed in this light, the Light Brigade’s attack was a total success. If Raglan had shifted to the attack, he might have scored a decisive victory against the Russians that day that would have shortened the siege.