By Christopher Miskimon

Henry Muller had an important job. He was the intelligence officer of the 11th Airborne Division, known in military parlance as the G-2. As 1944 ended, his unit was engaged in heavy fighting on the Philippine island of Luzon. His mission was to gather the intelligence needed to keep the division informed about the Japanese forces it faced.

One day he sat down with a Filipino plantation owner who had recently traveled the length of Luzon to get medicine from Manila for his sick wife. It was a good chance to learn what the enemy was up to and where they were gathering.

The interview began with Muller asking a few questions he knew the answers to so he could verify if the man was honest; the Japanese had collaborators among the island nation’s populace. Soon he was satisfied and began asking the farmer new questions, starting with what route the man took during his journey. Within a few minutes the farmer mentioned, “I went by that big POW camp.”

Muller was surprised; he knew of no such camp in the area. “What camp?” he asked.

“The one at the old Los Baños agricultural college.” The farmer explained it was full of American civilians, including women and children. It wasn’t far south of Manila. Muller asked how many prisoners were at the camp. The Filipino replied, “I’d say about two thousand.”

Muller’s shock deepened. He had no idea so many civilians were being held so close to the fighting. He extracted all the information he could about the camp’s location and circumstances. Afterward, he prepared a report for his division commander, Lt. Gen. Joseph M. Swing. His superior wasn’t surprised at the revelation, saying it wasn’t near their area of operations and not to worry about it beyond reporting the information up the chain of command.

Muller did as he was told but didn’t stop there. The Filipino reported the civilians were in bad shape; a liberation mission might be needed, and paratroopers were almost ideal for such an action. Quietly, he began gathering whatever he could find on the camp, it surroundings, and its defenses. If the opportunity arose to go to the rescue like the cavalry in a Western movie, the 11th Airborne would be ready.

The small Filipino town of Los Baños lies 40 miles southeast of Manila. At the edge of town sat the former grounds of the Agricultural College of the Philippines. On these grounds in February 1945 more than 2,000 American civilians were starving to death. They were desperate for help, but the advancing American army seemed far away.

The camp opened in 1943, constructed in an environment of contaminated water, malaria-ridden swamps and rice paddies, and a nonexistent sewage system. Lice and bedbugs infested the area, spreading disease. Water had to be brought from distant wells and boiled to make it potable. There was no electricity. The camp was built by 800 male internees selected mostly by lottery.

The bulk of the residents were moved there through 1943 and 1944 from other camps such as Santo Tomas. The Japanese wanted the Americans away from the Filipino populace at large. They encouraged the Filipino people to hate the Americans as deposed imperialist overseers, but the lesson hadn’t taken; the locals persistently aided the internees with food and clothing and occasionally helped them escape.

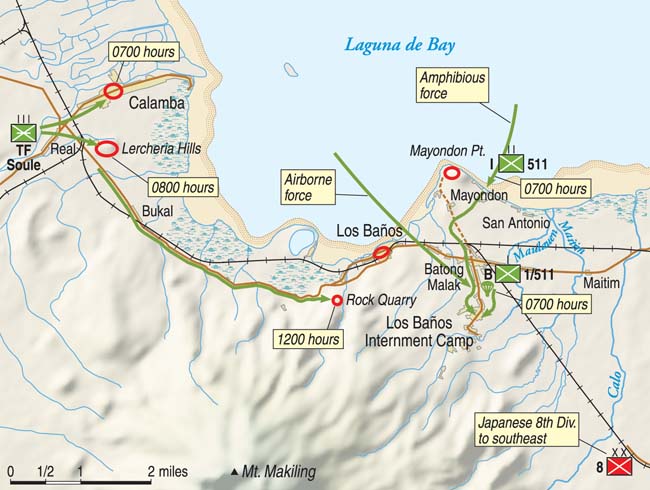

Aside from Los Baños, two other small villages sat nearby: Mayondon and San Antonio. An enormous freshwater lake, Laguna de Bay, sat to the north of the villages; the Americans held the opposite shore. Mayondon Point stood out on the lake, providing a vantage point to observe the area. National Highway 1 wound its way west to east, going through the villages alongside a rail line.

The camp was built on the grounds of the college’s athletic fields. The area around the camp was level, broken by a few streams and ravines. Vegetation covered the area. An inactive volcano, 3,576-foot-high Mount Makiling, sat to the southwest. The camp was 60 acres, roughly 600 by 800 yards. It was surrounded by a double fence of barbed wire; the outer fence was six feet tall and the inner four feet.

Segments of the fence were covered in mats called sawali. These gave concealment but not cover from gunfire or shrapnel. The main gate was on the northeast side with a smaller one on the southwest. The perimeter fence was dotted with nine guard posts made of logs and dirt. A tenth was outside the camp to the southeast. The barracks, arms room, and commandant’s offices were just inside the main gate.

There were 26 barracks buildings made of wood frames with nipa palm roofs; the walls were sawali mats. Each was 30 by 198 feet and sat on a concrete slab. The southwest portion of the camp was the “Holy City,” where the various priests, nuns, and missionaries were housed. The rest of the inmates lived in “Hell’s Half Acre” on the northern end.

The two zones were separated by a sawali fence. Outside the camp were the college’s concrete buildings and cottages, used as quarters for transiting Japanese units. They were unoccupied when the rescue occurred.

The first Japanese commandant of the camp, Major Tanaka, had actually been reasonably fair in his treatment. He was of a Samurai family and also a Buddhist priest. He showed concern for the welfare of his charges and even allowed them to undertake occasional trips to Manila to purchase food with their limited funds. Eventually he was replaced, but the new man, Major Urabe, was also relatively humane. Conditions were crowded and difficult, but the camp leadership did not seem inclined to add to their misery unnecessarily.

This all ended in July 1944 when the third commandant, Major T. Iwanaka, took command. Cruelty replaced humanity, and conditions deteriorated rapidly.

To the internees, Iwanaka appeared afflicted with what would today be called dementia. He left the day-to-day operations of Los Baños to a subordinate, Warrant Officer Sadaaki Konishi. Both seemed inclined to inflict as much suffering upon the internees as possible.

Still, the prisoners retained some hope. The Americans had landed in the Philippines in October 1944 and were fighting their way toward the camp. They saw air battles in the skies overhead, and bombers flew past on their way to Manila. Friendly Filipinos smuggled in food, and with it came news of the campaign. A few internees managed to acquire radios, carefully hidden and even more carefully listened to, away from the ears of the guards.

On the final day of 1944, a number of U.S. Navy fighters roared over the camp; the prisoners showed no outward display of elation for fear of reprisals from the guards, but inside they were ecstatic to see American aircraft.

A week later the Japanese guards burned the camp records. The next day the guards suddenly turned the camp over to the prisoners’ executive committee. Shocked by this development, the prisoners wisely chose to remain in camp, fearing the result if they ran into a roving Japanese Army unit or Filipino collaborators. In any event, they were too weak to get far. Later in the day a small number of Kempetai, the dreaded Japanese military police, arrived but did nothing more than close the main gate.

On January 9, 1945, another American landing took place in Lingayen Gulf, 160 miles north of the camp. The civilians were desperate for salvation, and the Japanese were equally desperate in their resistance.

Five days later the guards returned looking much the worse for wear. Major Iwanaka immediately imposed a strict curfew, reduced rations, and began unannounced searches. Tyrannical Warrant Officer Konishi denied food and medical supplies with increasing regularity. The internees grew steadily weaker, awaiting a rescue they feared would not come in time. Each day one or two more prisoners died.

Soon after the American troops came ashore, they began operations to rescue the thousands of civilians and POWs held in camps around the island. Many had been taken to Japan as slave labor, and there was growing fear those remaining in the Philippines would be murdered by the retreating Japanese.

Two successful rescue missions occurred in January and early February. The first involved a small force of Rangers working with Filipino guerrillas to liberate POWs at the Cabanatuan camp on the night of January 30. Some 522 were rescued—and the Japanese suffered heavy casualties—in what has become known as The Great Raid.

On February 1, another mission set out to free the Santo Tomas camp at Manila. With infantry riding tanks in a flying column, troops of the 1st Cavalry Division drove 100 miles in 66 hours, ranging far ahead of the main American advance. Aided by guerillas, they reached the camp and negotiated the withdrawal of the guard force, who soon became prisoners themselves. The column saved 3,700 internees.

Now the focus became the Los Baños camp. It was still deep behind the front lines, with thousands of Japanese troops in the area. The 11th Airborne Division was in the area, having made a seaborne landing in January soon followed by a parachute assault designed to trap local Japanese forces. This operation allowed the division to reach the southern outskirts of Manila by early February.

There, the Americans ran into the Genko Line, a Japanese defensive belt bristling with machine guns, bunkers, and cannons. It took weeks of hard fighting to secure the area, ending with the capture of the Cavite Naval Ammunition Depot on February 21.

While the 11th Airborne was fighting the Japanese, it also gathered the intelligence needed to plan a rescue operation at Los Baños. Their best estimate numbered the prisoners at 2,130. They assumed half were too weak to travel any distance and perhaps 250 were bedridden. The only military personnel present were a dozen Navy nurses. Fortunately, more information became available through the efforts of the prisoners themselves.

Each night a few prisoners would carefully sneak out of the camp to search for food and supplies. While foraging, they sought news of the American advance; usually there were more rumors available than food. Filipinos told them the U.S. Army was getting closer and Manila was close to falling.

A prisoner named Freddy Zervoulakos went out on February 12 and managed to contact Colonel Gustavo Ingles, a Filipino guerrilla leader. Ingles was scouting the area in preparation for the rescue mission. Zervoulakos gave the guerrilla officer information about the camp conditions and returned to inform the executive committee.

The committee debated what to do but feared Japanese reprisals. It ordered the prisoners not to contact Ingles again. Nevertheless, on February 18, Zervoulakos and three others—Pete Miles, Jack Connors, and Ben Edwards—snuck out of camp and rendezvoused with the guerrillas at a pre-arranged point. They aimed to get to American lines and ask for rescue.

The guerrillas took Miles across the lake in a banca, a canoe-like boat with outriggers. The next day Miles arrived at the 11th Airborne’s command post. He told them the location of the camp’s machine guns and their fields of fire, guard posts, and the routines of the sentries. Some of the guns were camouflaged and had not been detected by aerial reconnaissance. Significantly, most of them were sited to fire on the prisoners rather than defend against external attack.

The next step was a thorough reconnaissance of the area to verify the escapee’s reports and gain information. The leader of the divisional reconnaissance platoon paired up with an engineer platoon leader and the pair crossed the lake on February 20.

Their mission was complex but vital to the success of the rescue. They had to locate a drop zone (DZ) where the paratroopers could land. The DZ needed a route the Americans could follow to the camp for the attack. The two officers were also to determine the extent and locations of the camp’s defenses, including the guard posts.

Once across the lake, the lieutenants joined two of the American prisoners and some Filipino guerrillas. Silently they crept around the perimeter of the camp noting the defenses. They found two possible drop zones. One was south of the camp, but there was a creek barring easy approach to Los Baños. The other was northeast of the camp and easily large enough at 1,500 by 3,200 feet. At most a paratrooper would have to cover a few hundred yards to reach the camp.

There were also a few dry streambeds and ditches to provide cover fgor the attackers. This DZ had a railroad track along the northeast side and a set of power lines along the north corner, though power to the area was out. This would provide a boundary for pathfinders and aircrew to see the DZ during the drop. The American officers returned across the lake the next day and reported their findings, allowing the division staff to make detailed plans.

The actual plan for the rescue was both imaginative and daring. There were risks as well, but there was no way to know how long the prisoners had before the Japanese might execute them.

At the same time, the 11th Airborne was still actively engaging the enemy in hard fighting 20 miles west of Los Baños. Still, planning went ahead, and a coherent operation rapidly emerged. The rescue force would be divided into three elements, each with its own critical role.

The first was a company of paratroopers that would land on the camp and seize it from the Japanese guards. They would be assisted by men from the divisional reconnaissance platoon and local Filipino guerrillas. The recon men would cross the lake before the raid using bancas. They would kill or drive off the guards, collect the prisoners, and get them moving toward the lakeshore.

The second group would be a battalion of infantry riding in DUKWs—amphibious trucks. They would cross the lake, pull up onto the beach, and move to the camp to pick up the civilians, sparing the weakened prisoners a long trek before they returned across the lake to American lines. The DUKWs were later replaced with amphibian tractors, known as amtracs.

The third group was a battalion-sized task force that would approach the area overland as a diversion, drawing Japanese attention away from the rescue.

These three groups would carry out the plan in five phases, some of which would occur simultaneously. The first phase was the reconnaissance of the camp and planning of the mission, which was already happening. In Phase II, the reconnaissance platoon would link up with the guerrillas and secure the landing beach and drop zone. They would also kill the sentries.

Phase III would be the airborne drop and attack on Los Baños, including the preparation of the prisoners for evacuation. The evacuation of the civilians to American-held territory constituted Phase IV. While all this was going on, Phase V was the diversionary attack from the west, which would hopefully pull any Japanese reinforcements away from the camp.

There were a number of contingencies as well. There were hasty plans for an attack on the camp by the guerrillas if it appeared the Japanese were about to slaughter the prisoners. Another option was to evacuate the internees via the diversionary force in case an evacuation across the lake became unworkable.

The time for the attack was originally scheduled for late afternoon, but fears of the impending executions caused the attack to be moved to 7 am. This was also when the off-duty guards did their morning calisthenics. While exercising, they would lock their weapons in the camp arms room. Changes came rapidly due to the ever-evolving intelligence picture. Still, the 11th Airborne was able to smoothly adapt to changing circumstances.

The units selected as the mission parachute infantry were augmented by attached units of various sorts. B Company of the 1st Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment (1/511) was selected to make the parachute drop and assault the camp. Commanded by 1st Lt. John M. Ringler, it was a typical airborne infantry company with a headquarters and three rifle platoons. Each platoon had two 12-man rifle squads and a mortar section. The company was understrength at 73 percent with 93 men available.

B Company was actually the strongest unit in the regiment, despite its numbers. The company was reinforced with a nine-man engineer squad to set up roadblocks and the battalion’s machine-gun platoon, which had 28 men at the time. A trio of Filipino guerrillas volunteered to make the jump as well, and one war correspondent is known to have accompanied the mission, for a total of 134 men.

During the attack, the company would make its parachute landing and proceed by platoon to attack the camp rather than wait to assemble as a company. After eliminating any resistance, they would gather and organize the prisoners for evacuation.

The reconnaissance platoon would infiltrate the area by crossing the lake in bancas and take positions around the camp. They would mark the drop zones and landing beaches and assist in the assault. With them would be guerrillas from several different groups. Weapons, ammunition, and supplies were funneled to the guerrillas to aid in their efforts.

Lieutenant Colonel Gustavo Ingles of the Hunter’s ROTC guerrilla group was in charge of planning. Ingles had the respect of local guerrilla leaders, so he could work through any difficulties. On February 10, a meeting was called with the guerrillas to discuss whether they could take the camp and liberate the internees without American troops. They were not sure if the paratroopers could be withdrawn from the front quickly enough before the rumored executions took place.

While the guerrillas believed they might be able to take the camp themselves, they had no solution for evacuating the internees, who would be too weak to walk to the American lines. The guerrillas had no trucks and were unsure whether they could hold the camp against counterattacks until the Americans arrived. It was decided to try and wait for the U.S. assault with one caveat: if the guerrillas observed the Japanese killing prisoners, they would attack immediately to save as many as they could.

The guerrilla leaders had one other concern. Even if the prisoners were successfully rescued, the Filipino people living in the area would then be at risk; the Japanese often retaliated against local civilians wherever a guerrilla attack took place.

It was unknown when the American advance would seize the area, which troubled most of the guerrilla leadership. Colonel Ingles finally calmed their fears by saying he would recommend attacks against the nearby Japanese units after the raid to keep them pinned and unable to carry out reprisals.

On February 13, Ingles went to the camp to observe it. He also met with George Gray, a recent escapee and the former secretary of the camp’s committee. They discussed the guard posts, the routines of the guards, and the deteriorating situation inside the camp. Ingles received orders the next day to send a patrol to the lakeshore and check the ground to be sure it would support the weight of motor vehicles. They would also check the road from the shore to the camp. This patrol took place on the night of February 16.

Ingles returned to the American lines and met with the 11th Airborne staff. He reported the guerrillas could seize the camp but probably could not hold it against a Japanese counterattack. The 11th Airborne was part of the U.S. Eighth Army under the command of Lt. Gen. Robert Eichelberger, who discussed the plan with intelligence officer Major Day Vanderpool. There were doubts as to whether the guerrilla forces could assemble and move through the area without being spotted or betrayed. They decided to cancel the unilateral guerrilla mission and focus on the combined airborne and amphibious assault with the Filipino forces in support.

At some point during the later planning stage, amtracs were substituted for the amphibious trucks, though it is unknown exactly why. In any event, the amtracs had deeper cargo compartments and somewhat better protection. They were also armed with more .50-caliber machine guns than DUKW units generally carried.

It was a risky decision; amtracs broke down more often, and the loss of even a few might leave the mission without enough vehicles to carry everyone. The unit selected was the 672nd Amphibian Tractor Battalion, which had been in combat since Bougainville in September 1944. It was equipped with the LVT(4), a 24-foot-long tracked vehicle with a 250-horsepower gasoline engine and a crew of three. The LVT(4) also had a rear ramp that would make it much easier for the weak internees to get aboard.

The battalion had 54 amtracs available for the operation. The other two rifle companies of 1/511 would ride in the amtracs and help secure the area.

The diversionary force was under the command of Lt. Col. Robert Soule and hence became known as Task Force Soule. It was composed of the 188th Glider Infantry Regiment, minus its 2nd Battalion. The 2nd Battalion of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment was also committed as the task force reserve. A pair of artillery battalions, the 472nd and the 675th (Glider), both equipped with 105mm howitzers, would provide fire support.

Company B of the 637th Tank Destroyer Battalion was attached, adding mobile firepower to the column. The American force was rounded out with a company of combat engineers and a detachment of bridging engineers. A large number of Filipino guerrillas from the Hunter’s ROTC group also accompanied Soule’s unit.

Japanese troops were scattered throughout the area. Many of their positions posed a threat to the rescue, although American intelligence efforts revealed them so planners could deal with them. There were an estimated 150 to 250 troops in the camp’s guard force; even the prisoners were unsure of the exact numbers. While the American planners had to assume they were seasoned veterans, most of them were older men past their prime or recuperating sick and wounded. The guards would change shifts in the morning when the men not going on duty would report for calisthenics.

There were many more Japanese troops in the surrounding area. The lake was covered by a detachment of 20 men on the Los Baños wharf with a pair of 70mm cannons just west of Mayondon Point. These guns could endanger the amtracs as they crossed the lake.

There was a rock quarry about 3,000 yards west of the camp. A company-strength force was stationed there with four machine guns and a pair of howitzers. Over six miles to the west was a detachment of 80 troops and two 75mm guns set up as a roadblock along National Highway 1. This force was in the path of the Soule Task Force. A number of Japanese patrol boats cruised the lake, but they were not considered a real threat to the amtracs.

By far the largest threat to the rescue force was the Japanese 8th Infantry Division, between 8,000 and 10,000 strong. This unit served in Manchuria from 1939-1944 and was an experienced formation consisting of two infantry and one artillery regiments. While it would take hours for the 8th to move to Los Baños, one of its battalions was able to move to the camp in 90 minutes once it learned of the situation and received orders. If the rescue was delayed, the 8th Division could endanger the success of the entire operation.

Despite the risks, the operation began on February 19 when B Company was pulled from the line and taken by truck to New Bilibid Prison, also located on the shoreline of Laguna de Bay. The men rested for a day and were then briefed on the rescue mission. Their reactions were mixed; while most understood how important this was for the prisoners and were honored to be selected for the effort, a few thought it was a suicide mission and did not mind saying so.

The company had three Filipino guerrillas who were “adopted” during the fighting in Manila and were assigned one per platoon. A sergeant asked 1st Lt. Ringler if the guerrillas could go on the raid. Ringler agreed, so the three Filipinos were given three hours of parachute training. The battalion machine-gun platoon, commanded by 2nd Lt. Walter Hettinger, arrived the next day.

While the company prepared for its new mission, planning went ahead. Changes came quickly so that few written orders were even prepared; the actual written orders for the mission were created afterward purely for historical documentation. While the risks were still considerable, the division staff and command personnel thought the goal was still worthy. On the 20th, the 65th Troop Carrier Squadron was assigned to carry the paratroopers for the drop.

Commanded by Captain Donald Anderson, the squadron was equipped with Douglas C-47 Dakota transports based at nearby Nichols Field. It had last dropped paratroopers during training exercises at Fort Benning, Georgia, before it went overseas but was still considered capable of performing the mission.

During the late afternoon of the 22nd, B Company was trucked to the airfield and issued parachutes and assigned to the planes in 15-man sticks. A few of the men carried extra ammunition and submachine guns to arm the local guerrillas. Each man was given a map of the camp and briefed on the latest updates.

The attached engineers also arrived and were ordered to establish roadblocks near the camp to delay any fast-arriving Japanese. The men were also informed they would jump at a much lower altitude than the normal 1,000-1,200 feet. Instead, they would jump at 400-500 feet; this would get them on the ground more quickly and closer together. From this height, the time in the air would be only about 25 seconds.

Meanwhile, on the night of the 21st, the reconnaissance platoon, under the command of 1st Lt. George Skau, began infiltrating into the Los Baños area. Skau led one group with three of his scouts and a trio of war correspondents in bancas; Sergeant Martin Squires took charge of another group of five scouts the same way for the three-hour trip across the lake. A large banca rigged with sails carrying the remaining 23 men of the platoon left two hours later. This vessel also carried the unit’s machine guns and heavy equipment.

The winds blew against them that night, however. It took Skau’s group eight hours and Squires’ men 10 hours to get across the lake, arriving only shortly before sunrise. They rendezvoused with the local guerrillas at a schoolhouse and prepared for their mission. The large banca still had not arrived.

The plan was for the platoon to divide into six teams, each of which would have six to eight guerrillas attached. The team under Sergeant Turner would mark the drop zone with green smoke just before the planes arrived overhead. Sergeant Leonard Hahn’s team would secure the landing beach for the amtracs and mark it with green smoke.

Skau and three sergeants, Robert Angus, Vinson Call, and Cliff Town, would all lead teams that would eliminate the guard posts on the north and west sides of the camp. Skau’s team would personally attack the guard post at the main gate. Another would cut through the fence and seize the arms room.

Another team led by Sergeant Squires was bolstered with 20 guerrillas and assigned to hit the guard posts on the southwest side, while another led by a radioman would cover the south. Even a few escaped prisoners were located and added to the teams.

Finally, on the evening of the 22nd, the large banca carrying the rest of the platoon arrived; it had been stuck in the middle of the lake, becalmed. Luckily, no enemy patrol boats had spotted them. After dark, the soldiers left the boat and were quickly briefed on the plan before setting out for their assignments.

Silence was imperative. If the American troops were discovered, the Japanese might start executing the prisoners. Skau even told them not to return fire if they were shot at in the darkness. It wasn’t unusual for sentries to shoot at noises in the nighttime jungle.

As the scouts moved into position, Task Force Soule was also preparing for its mission. The attached engineers were busied repairing or replacing bridges. The Hunter’s ROTC guerrillas arrived and were assigned to guard Soule’s flank. The 672nd Amphibian Tractor Battalion also assembled on the American side of the lake.

As the combat soldiers waited, the division staff kept gathering information through the night. Around midnight a Northrop P-61 Black Widow night fighter overflew the area and reported “hundreds of truck headlights” moving toward the Los Baños area from the east and then returning.

The staff also received a report from some guerrillas that 3,000 Japanese had arrived as reinforcements. General Swing considered these developments but decided to continue as planned; changing the operation would upset the carefully constructed timeline and lead to the separate units arriving at varying times, unable to support each other. It was later learned the reports were overblown.

On the Japanese side, many of the American movements had been detected but the wrong conclusions were drawn. Task Force Soule was observed, and the Japanese took it to be the main attack. They dug in to await it. The amtrac battalion was also reported but assessed to be tanks supporting Soule’s advance. It did not seem the Japanese considered so much effort might be put into rescuing internees. The guards at the camp passed the night with no idea what was coming.

The attack actually began at 4 am on February 23, when the troops assigned to the amtracs loaded into the vehicles. Aboard one was Major Henry Burgess, the parachute battalion commander who was in charge of the entire operation. Lt. Col. Joseph Gibbs, the amtrac battalion commander, was also aboard.

At 5:15 the entire force of 54 amtracs formed into three columns of 18 vehicles each and moved into the lake. At 5:50 they turned south using handheld compasses and estimates of the distance travelled at their speed. This was risky since the crews had no experience at navigating long distances; they were used to moving supplies and troops ashore from transports.

The plan worked, and at 6:20 they made a small correction that put them on course for the beach at San Antonio. The rising sun gave them a first view of their objective. Suddenly, the nine C-47s carrying B Company raced overhead, causing the paratroopers in the amtracs to note how low the planes were flying.

The dawn brought enough light for the pilots to easily spot the terrain features around the camp. Below, Sergeant Turner’s scouts lit off their green smoke grenades, marking the drop zone for the pilots above. Lieutenant Ringler stood in the door of the lead plane.

At the landing beach two miles from the camp, Sergeant Hahn’s team also lit their green smoke for the approaching amtracs that had navigated nearly perfectly. The unit divided into nine columns of six vehicles; not a single amtrac broke down during the 74-minute trip. Scouts and guerrillas ran up to direct the vehicles to the road.

One platoon from A Company jumped off to secure the beach along with two jeep-drawn 75mm pack howitzers loaded on the amtracs. The Japanese guns on Mayondon Point began firing at the unit, and the American artillery quickly went into action while the rest of the amphibious assault advanced toward Los Baños.

As the amtracs rolled ashore, B Company got the green light to jump at 6:58. Ringler leapt from the doorway, and his men followed, one every second. Due to the low altitude, the trip to the ground was short. As they landed, the paratroopers shed their jump harnesses, gathered their crew-served weapons from the drop bundles, and formed up for the attack on the prison guards and the liberation of the camp.

The scouts had struggled through dense jungle and across deep creeks to get into position on time; several arrived with just minutes to spare. Squires’ team had gotten separated from its accompanying guerrillas in the darkness. With 15 minutes to go until the attack, one of the guerrillas was attacked by a villager’s dog. He drew his pistol and shot the animal down, causing the entire team to stop motionless, awaiting the response of the Japanese. Inexplicably, none came, so the team finished moving into position.

Nearby, Sergeant Town’s team was also just arriving in position as the attack began. One of the guerrillas was hit, but his life was saved by his belt buckle, which shattered the bullet. They heard some gunfire from the other side of the camp and immediately saw four Japanese soldiers running across a field in front of them. Pfc. Robert Carroll opened fire on them with his BAR, emptying the magazine in one long burst. All four enemy troops were cut down in the fusillade.

Continuing their attack, the team found another Japanese crawling through a ditch and shot him as he tried to escape. Most of the guerrillas ran off to chase down fleeing Japanese while the Americans starting cutting the wire to get into the camp.

A few other teams were late but quickly got involved. Lieutenant Skau’s team was still several hundred yards from the front gate when the shooting started. Carrying the platoon’s only machine gun, they rushed through the gate without suffering any casualties; the team kept going to the arms room and took control of it. Along the way, they shot down a number of guards.

Incredibly, the Japanese soldier in charge of the off-duty guards, who had just assembled for their morning calisthenics, ordered them to their barracks to put on uniforms rather than straight to the armory for their weapons. It was a fatal mistake.

The rest of the reconnaissance platoon was quickly engaged with the Japanese guards while B Company was still landing nearby. Sergeant Call’s team came under machine-gun fire from a position north of the main gate. They were also pelted with grenades, one of the fragments hitting a man in the nose.

Call was hit in the shoulder by the machine gun, but the team kept moving forward, shooting at guards within the camp. When the sergeant noticed some guards taking cover in a bunker near the main gate, he called B Company to put some 60mm mortar rounds on it. The team also hit the bunker with grenades.

The rest of the teams got into the camp and started shooting the guards, many of whom were running around seemingly without direction. Some hid in prisoner barracks, while others scrambled into ditches or tried for their own barracks. Some went for the arms room, but Skau’s team cut them down, including an officer who tried to jump through a window into the camp headquarters.

Many of the Japanese, particularly the unarmed, fled into the jungle or nearby buildings. Most of the Filipino guerrillas broke from the American scouts to chase down the fleeing men, often hacking them to death with bolo knives or machetes. The Filipinos were taking revenge on the hated Japanese for all they had done to their country.

When the attack began, most of the internees were assembling for the morning roll call. It took a short time for them to realize what was happening. When they saw the parachutes start disgorging from the C-47s, many thought it was a food drop. A few claimed to see a Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter fly over with the word RESCUE painted on its side.

The scene quickly became chaotic. Nuns began praying; people started shouting, while others returned to their barracks to gather belongings. When the bullets began flying, most took cover in ditches or the barracks; a few just dropped to the ground and lay prone. One woman spotted paratroopers at the wire cutting their way in. Thinking quickly, she grabbed a pair of wirecutters, ran over, and gave them to the soldiers.

B Company burst in on the fighting and began to do its part. The jump had gone well, and the company had amazing luck. Only one man suffered an injury from the landing, but it was not serious enough to stop him from joining his comrades. The entire unit landed together, even the Filipinos, who had never jumped before.

Within 15 minutes, the lead paratroopers entered the camp. Only a few shots were fired at them, and the offenders were quickly dealt with. The Japanese resistance, never truly organized, was nearly over, and the Americans started mopping up the remainder. Most of them consisted of guards who would pop up here and there among the 2,100 civilians, but only a few fought. Most were simply trying to escape, but the paratroopers shot them as they ran. The Americans were there to rescue the internees and get away as quickly as possible. They took no chances by sparing the enemy.

With the main fighting over, most of the paratroopers set about organizing the civilians for the evacuation. The attached engineers ran down the road to their roadblock positions. They laid mines, prepared satchel charges, and blew down trees to block the roads the amtracs didn’t need to use. Each roadblock was covered with a machine gun in case the Japanese arrived quickly.

Soon rumbling noises were heard from the direction of the lake. Some of the prisoners became frightened, thinking the noise came from Japanese tanks. Instead, a long column of amtracs appeared and drove through the main gate. None of the internees had ever heard of such a vehicle but were glad to see they were American.

The two infantry companies aboard the vehicles dismounted and secured the area as best they could. The 50 men of A Company stayed in the camp, while C Company set up more roadblocks. Only six amtracs would fit in the camp entrance, so the rest parked on a baseball field and some open spaces outside the main gate.

As the paratroopers deployed, a strange event took place. A colonel from MacArthur’s staff, Courtney Whitney, emerged from an amtrac with an interpreter and two of the amtrac’s crew. They went to the camp’s headquarters building and returned shortly with boxes of documents. Whitney stated he was along only to observe the operation. He was, in fact, the man in charge of that section of MacArthur’s staff responsible for liaison with Filipino guerrilla groups. They returned on the same amtrac, and the significance of the documents is unknown to this day.

The civilians had not seen an American soldier in three years and were amazed at their appearance. Some didn’t recognize them at first. They wore strange helmets, different from the World War I-style headgear in use at the war’s beginning. Their uniforms were dark green, closer to the Japanese uniforms rather than the khaki they were used to. Many of the paratroopers had yellowish skin from the Atabrine they took to ward off malaria.

The rifles, submachine guns, and bazookas they carried were likewise unfamiliar to the prisoners. The paratroopers looked like giants. The civilians were all starving, many weighing under 100 pounds. The paratroopers were all in good health and physical condition. They towered over the civilians.

The American soldiers were similarly shocked by the internees, who appeared no more than skin and bones. Many were ill, wore little more than rags, and some were so frail the paratroopers were afraid to pick them up for fear of injuring them. Some were so hungry they ran to the kitchens and storerooms to eat. Others were disappointed to learn their liberators were soldiers; they’d dreamed of being rescued by Marines.

There was a wide range of emotions. Some cried, while others were euphoric. A few hid or even refused to cooperate, perhaps afraid the Japanese would return. It was obvious they could not make the 21/2miles to the beach.

On a happy note, one of the accompanying war correspondents came along because his brother and sister were internees in the Philippines. He found them almost as soon as he entered the camp.

The problem became organizing the civilians and getting them aboard the amtracs. Most were milling around, and no one was in control. Major Burgess got them under control and made sure his men were all accounted for. At 07:45, Lieutenant Skau reported his men were all present, but most of the guerrillas were gone hunting Japanese. They would be of no use if the Japanese appeared.

Ringler knew where most of his men were and was tracking down the last few. Burgess was also unable to contact either Task Force Soule or division headquarters by radio. They could hear firing in the direction of Soule’s unit, but it didn’t seem to be getting any closer. Lt. Col. Gibbs wanted to be released to take his amtracs back across the lake and leave the internees and paratroopers to join up with Soule.

Burgess refused this request; he would have to evacuate all the internees by amtracs across the lake as planned. Unfortunately, the 54 amtracs could not carry all the civilians and soldiers in one trip; he would send as many as possible in one lift. The rest of the internees would have to wait for the second lift, protected by a perimeter of paratroopers arrayed around the beach.

This would be difficult as the beach was on low ground and hard to defend against a concerted attack; it might take two or three hours for the amtracs to return. Still, the paratroopers had plenty of ammunition and their two howitzers. It could be done, and there was no other choice.

The task of getting the civilians into the amtracs was made easier by a fire that started in the headquarters building. The internees were naturally moving away from it and toward the parked vehicles. Burgess ordered Ringler and the machine-gun platoon leader to set fire to the barracks and force the prisoners away from them. This had the desired effect, and soon the paratroopers were helping the frail civilians aboard the transports. A few men searched the camp to ensure none were left behind.

As the remaining internees entered the amtracs, the rest of the B Company men were accounted for with only two casualties, both minor wounds. The convoy moved out, heading back to the lakeshore, each vehicle packed with liberated civilians while paratroopers marched alongside, escorting them toward freedom.

Along the route, Filipinos gathered from the villages, passing water and bananas to the Americans. The camp was empty and burning to the ground. The B Company men were the last out after a final sweep. A few stragglers were with them, and many of the soldiers carried babies. They trod past the corpses of Japanese guards and went down the road.

While the paratroopers made their stunningly successful raid on Los Baños, Task Force Soule was equally busy diverting Japanese attention. The task force began its mission with its artillery, raining shells on the Japanese in the nearby hills and the rock quarry. The infantry advanced, purposely making noise. The tank destroyers moved constantly to make it seem there were more of them. The trucks dragged logs behind them to raise dust and make the battalion appear to be a division.

Lieutenant Colonel Soule was methodical, clearing the nearby hills and repairing bridges to ensure the task force could withdraw easily. At this point he assumed the amtracs would withdraw with his force after they rendezvoused. Some of his troops supported an attack by the guerrillas on a nearby hill with their machine guns and mortars. A number of Filipino bodies were found with their hands tied, but the Americans didn’t know if they were collaborators executed by the guerrillas or victims of those collaborators themselves. Three Americans were killed during the task force’s diversionary attack.

At the lakeshore, the paratroopers formed a perimeter around the beach as the internee-filled amtracs arrived. Major Burgess still wasn’t sure the Soule Force was on its way, but it was time to move the civilians across the lake. It was 11 am, and the round trip would take at least two hours; the paratroopers dug in while 1,500 of the internees were loaded aboard the amtracs. The remainder waited.

The vehicles formed into three columns and began their journey. An occasional bullet snapped past from the shoreline, and the amtrac crewmen responded with machine-gun fire, drenching the beach and nearby jungle in a torrent of lead.

The paratroopers from the blocking positions collapsed in on the perimeter. There were a few contacts with Japanese troops, but they amounted to little. About noon, General Swing flew overhead in an L-4 liaison plane and established radio contact through a forward observer.

Burgess told Swing the prisoners were moving over the lake. Swing was happy the operation had gone so well with so few casualties. The division commander then suggested to Burgess that once the last internees were gone, he should take the rest of his troops and link up with Soule’s task force.

Burgess realized this was a bad idea and did the only thing he could to avoid being ordered to do it. He turned off his radio and continued with his plan. Luckily, Swing never made an issue of it later, likely realizing his error.

Just after 1 pm, the amtracs returned and loaded the rest of the civilians, followed by the paratroopers. The artillerymen hurried their pack howitzers to the beach. The jeeps and guns were loaded on separate vehicles, with one cannon laid across a pile of baggage. Japanese fire from Mayondon Point and the rock quarry grew heavier.

The crew of the baggage-mounted cannon aimed their gun at the point and fired. The recoil of the 75mm shell nearly swamped the amtrac, and the angry driver threatened to shoot them if they tried to fire again.

The diversionary force saw the prisoners evacuating across the lake, so Soule decided to withdraw to the San Juan River, staying on the near side in case he had to advance again. There was a small counterattack by 50 Japanese troops, but it was easily defeated.

While the amtracs ferried the second group, the first group was taken by trucks and ambulances to nearby New Bilibid Prison. The ex-prisoners were taken aback to be quartered in cells, but nevertheless it was a happy time. Doctors and medics examined the civilians, and new clothing was given to them. A chow line was opened, and some went through it four times. To help their sensitive stomachs, the food consisted of fresh bread with butter and bean soup.

Newsmen walked among them, taking photos, interviewing, and filming the joyous occasion. The second group arrived safely, and by 4 pm all the civilians were together. An hour later, the rescuing paratroopers reached the prison/hospital to the cheers and applause of the rescued. They all shared a meal, and the airborne men were allowed to stay the night, spending it celebrating with the now free civilians.

The next morning, they ate breakfast and boarded trucks; it was time to go back to the war. The 1/511 soon relieved Task Force Soule. A few days later, they advanced and discovered the Japanese had massacred 1,500 Filipino civilians as a reprisal for the raid. Warrant Officer Konishi was found months later and hanged in 1947 for his war crimes. Major Iwanaka escaped.

B Company received a Distinguished Unit Citation for its role in the rescue. The camp site is now part of the University of the Philippines; the grounds are a park containing a massive rain tree called the Fertility Tree, where young couples meet.