By Kevin M. Hymel

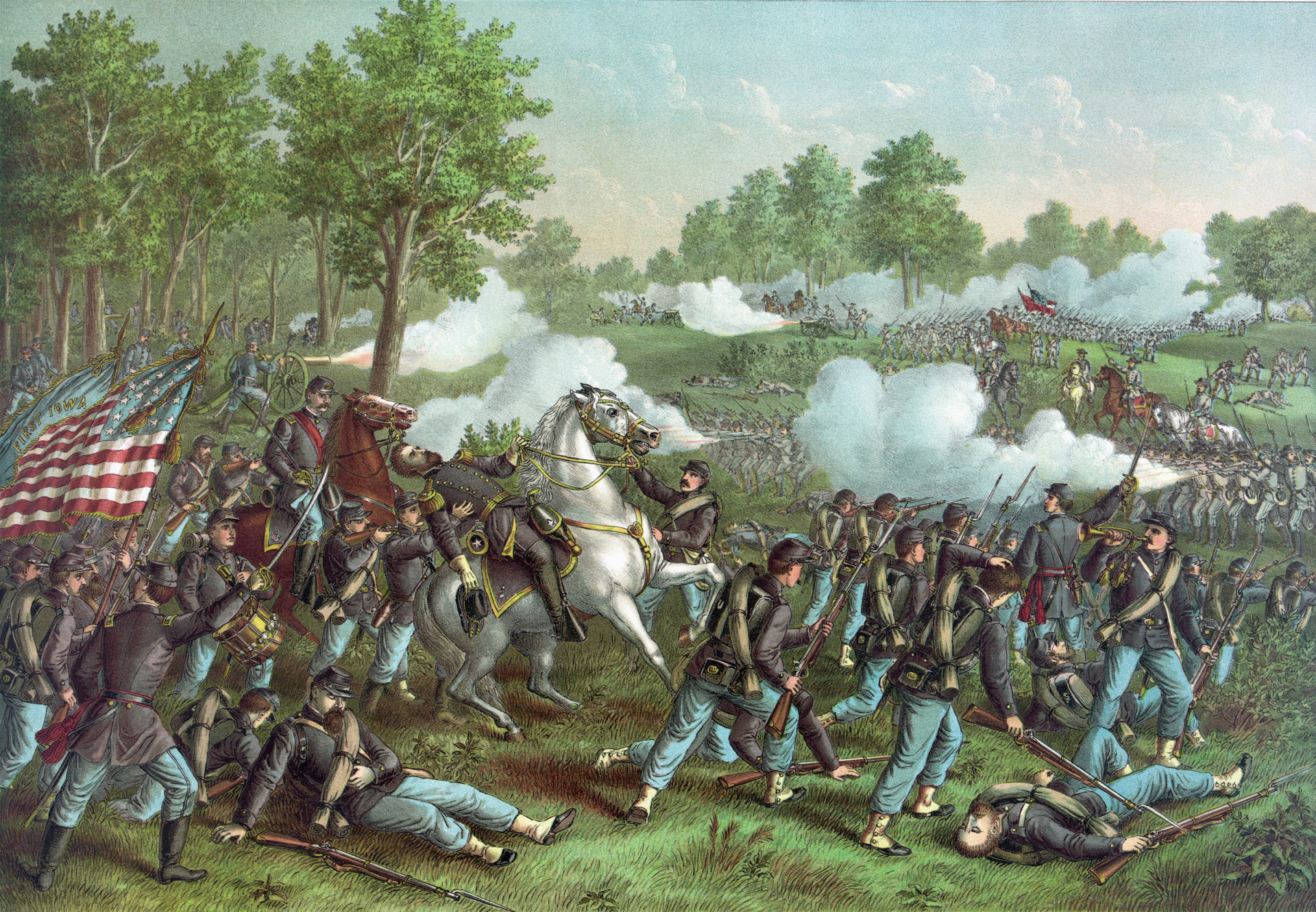

Private Leon Goldberg pulled the trigger on his heavy, water-cooled M-1917 Browning machine gun and fired bursts of .30-caliber rounds into the attacking German infantry. The Germans below the forested hilltop Goldberg and his comrades occupied had to cross a stream and charge uphill to engage them. American riflemen added to Goldberg’s torrent of fire as the Germans collapsed in the snow. Goldberg could see a dead German lieutenant at the bottom of the hill, lying half in the stream.

“The current washed his leg up and back,” he said. Those who survived the fire, about 20 Germans, surrendered to the Americans. “The troops who attacked us were certainly not the best troops,” he explained. “They were pretty green and relatively young.”

The Americans, who were also green, felt proud of their baptism of fire. “We thought we had won the war,” said Goldberg, a member of Company D, 422nd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division (the Golden Lions). But they had not. The date was December 16, 1944. The attack was just the opening assault of Adolf Hitler’s last gamble to win the war in the West—the Battle of the Bulge—in which three German armies smashed into Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ First Army with the goal of splitting the Western Allies and capturing the Belgian port of Antwerp.

Simultaneous with the German attack had come an enemy artillery barrage that screeched over Company D, which targeted the division’s own artillery, killing Goldberg’s battalion commander, Lt. Col. Thomas Kent. Major William Moon took over. The weak enemy attack had been a feint, while other Germans encircled the regiment.

But Goldberg knew none of this. He had done his job, repulsing the enemy, yet had little time to reflect on his actions. Soon, the order came to move out. The men pulled back to the outskirts of the Belgian town of Schönberg, where they set up on the edge of the forest overlooking a wide valley that sloped down and then up to another forested hill about 400 yards away.

“We got orders to attack,” explained Goldberg.

He ran with the other men across the valley, but he stopped halfway and set up his machine gun to fire over their heads, while another machine-gun crew leapfrogged from behind him. When Goldberg saw enemy fire coming from an open cabin door, he zeroed in on it, watching his tracers pepper the door frame. He later learned that experienced gunners removed the tracers from their rounds, since the enemy could follow them back to the source.

“I wasn’t in combat long enough to do that,” he said.

No sooner had Goldberg fired on the cabin door than the attacking infantrymen came running back from the woods, calling out that they had seen German tanks. Goldberg could hear the sounds of the attack, but did not stick around to see what was happening. He and his second gunner disassembled the machine gun and joined the retreat.

The men pulled back and set up in another location. “We were just waiting to see what happened next,” said Goldberg. “The enemy approached, and we retreated again.” And so it went for the next two and a half days. With the Germans encircling the regiment, the men ran from position to position, trying to stay away from the enemy. The Golden Lion men dug in, set up, fired at the Germans, then ran to another position. They rarely ate or slept and were running low on ammunition and fresh water. “You tried to close your eyes while other men stood guard, and if you did fall asleep, someone would wake you up and tell you to move,” explained Goldberg. Through it all, none of the men panicked or complained, but “everyone was exhausted.”

Despite the fighting, Company D remained mostly intact. On the third day of combat, December 19, the men were dug in atop a small hill when a German officer approached, waving a white flag on the end of a rifle. Goldberg’s lieutenant went out to talk to him and then followed him back to the German lines. The lieutenant returned an hour later and told everyone they were going to surrender. “He told us the Germans had a lot of armor, and it would take them 15 minutes to blow this area to smithereens.”

“Nobody wanted to surrender,” said Goldberg, “but we had to. We had a habit of obeying officers.” The riflemen removed the firing pins from their rifles and threw them away, then broke up their rifles. “Then we marched out.” The lieutenant led the men out of the woods to a small town where they sat down on the grass beside a paved road. The Germans came by and checked the Americans’ pockets. Goldberg said, “I had nothing to give them, but they did take things from the others.”

Goldberg grew apprehensive as the Germans rifled through his fellow GIs’ pockets. He knew his dog tags possessed a single letter that could immediately change his treatment. The letter was an “H,” which stood for Hebrew.

Goldberg had grown up in a Jewish household in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His parents, Russian immigrants, brought their three boys, Martin, Leon, and Edward, to B’nai Abraham Synagogue for all the high holidays. When war broke out in Europe and Asia and war clouds neared the United States, Leon’s older brother Martin joined the Army and went to work on something called Manhattan. Goldberg found out 50 years after the war that he had been working on the Manhattan Project, the development of the first atomic bomb.

Goldberg was a 19-year-old student at Overbrook High School when he learned about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He ran track and cross-country and had a girlfriend, Esther Meadow. After graduation, he enlisted in the Army, but when he received no notification to report, he registered at the University of Pennsylvania, where he had been accepted for early admission. He had completed a year and a half of studies when the Army sent him to the Infantry Replacement Center at Camp Wheeler, Georgia, for nine weeks of basic training.

Goldberg was then selected for Officer Candidate School (OCS). Two weeks before basic training ended, he was picked for the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), which sent qualified candidates to college to study medicine, dentistry, or engineering. Goldberg chose engineering and traveled to Alabama Polytechnical Institute, today’s Auburn University. “I went to college during the week, but weekends were free,” he said. “I thought I would never go overseas.” While in ASTP, he married Esther, and the two rented a room in a professor’s house.

After Goldberg had spent three semesters at Auburn, the U.S. Army became desperate for frontline soldiers and disbanded the program in February 1944. Goldberg was sent to Camp Atterbury, Indiana, where he joined Maj. Gen. Alan W. Jones’s 106th Infantry Division and was assigned to Captain Charles Porter’s D Company in the 422nd Infantry Regiment. Esther soon joined him and rented a room in a farmhouse outside the camp gate. “It wasn’t easy,” said Goldberg, “but it was great.”

Goldberg trained as the first gunner on the M-1917 water-cooled Browning heavy machine gun. When moving, he carried the machine gun’s 50-pound tripod over his shoulders, while the second gunner carried the barrel. “I would swing the tripod off my shoulders and set it down,” he explained. “Then the second gunner set the barrel, locked it, and fed it ammo.” Fully assembled, it weighed 103 pounds. Goldberg would then man the machine gun. Two soldiers carried extra water for the barrel to ensure it would not overheat, while three other men carried extra ammunition. For his own protection, Goldberg carried a Colt .45-caliber pistol.

In October 1944, Goldberg and his regiment shipped out to England aboard the RMS Aquitania, a British passenger liner converted into a troop ship. The ship was fast enough to travel without an escort, zigzagging for eight days as it made the journey. “I was sick the whole time,” he recalled. “I was not a good sailor.” His quarters were stuffy, the air stale. “The previous soldiers had cut holes in the air conditioning ducts so they could get air down there.” He spent most of his time up on deck “getting sick.” His meals consisted of cheese and bread with an occasional plate of scrambled eggs.

The ship arrived in England on November 1, and the Americans trained for a month at Batsford Park outside Oxford. During training, Goldberg would hear German V-1 “Buzz Bomb” pulse jets flying overhead and see an occasional explosion. “It was really scary,” he said. “We could hear them and see some of them. We felt bad for the people under assault.”

On November 26, the division shipped across the English Channel to Le Havre, France, where Goldberg got his first sight of the war’s destruction. “There were sunken ships in the harbor and nothing but devastation in the town,” he explained. “It was a horrible sight; it made us realize how bad things really were.”

They headed to the front to replace the veteran 2nd Infantry Division east of the Belgian town of Schönberg on the German border on December 11. As Goldberg and his comrades marched into the woods, the 2nd Division infantrymen walked past in the opposite direction. “Go get ‘em!” the veterans encouraged. Some gave their overcoats and overshoes to the green soldiers. “That helped us a lot,” said Goldberg. “We were anxious to fight.”

The Golden Lions occupied the veterans’ positions and resided in cabins built three feet above the ground. In the December snow and winds, the men stood guard in their foxholes and rotated two hours on the line and four hours off. “We didn’t expect any action until spring,” Goldberg said. Still, he could hear enemy activity. “We heard lots of noises on the other side of the mountain.” He heard German trucks and tanks. He learned later that

scouts had reported activity back to headquarters, but their warnings were either ignored or responded to quite slowly. “We just kept patrolling and manning our positions.”

Goldberg and his crew set up their machine gun atop a slope that overlooked a stream. Sergeant John Adams commanded the crew. “He was a tall, slender woodsman from West ‘by God’ Virginia,” said Goldberg. “He loved the outdoors and was very much at home out there. He was a great leader.”

On the morning of December 16, German artillery screeched over Goldberg’s position. Almost simultaneously, German infantry charged across the stream, and Goldberg opened fire. For three and a half days, the men of D Company fought the Germans wherever they encountered them. When the men were finally ordered to surrender, Goldberg worried the Germans would see the “H” on his dog tags and single him out for punishment, or worse. “I was the only Jewish soldier in the company that I knew of,” he explained. “I didn’t know what was going to happen.”

But the Germans made no move to check his dog tags. Instead, they organized the Americans into rows, four abreast, and began marching them east into Germany. Altogether, they had captured some 7,000 GIs from Goldberg’s 422nd Infantry Regiment and the 423rd. It was one of the worst defeats in American history. The men marched for eight days through forests and towns, stopping periodically for rest. “They did not feed us except for a large piece of bread about the size of your fist once a day,” explained Goldberg. The captors also passed out buckets of drinking water.

One day, they marched into a city under an arch that spelled out “COBLENZ” in large metal letters. They slept that night on pieces of slate in a factory. “At night, we were lucky to have some shelter,” said Goldberg. The men eventually reached a railroad siding and were put into 40&8 boxcars. “They packed us in so tight we couldn’t sit. We were shoulder to shoulder,” he recalled. As they headed east, American fighter aircraft strafed the train and dropped 500-pound bombs. “The bombs never hit the train, but the strafing did.”

As planes swooped in, the train stopped and the Germans ran into the woods, leaving the Americans in the boxcars. “I could see planes diving on targets through the slits in the boards in the boxcars,” said Goldberg. “We were just sitting ducks. I could hear the bullets tear through the boxcar, and all you could do was pray.” One round hit the soldier next to him.

The fighters flew away, and the Germans returned and opened the sliding doors. Goldberg moved away from the soldier. “He never made a sound; he just dropped,” he said. “I’m sure he was killed.” The Germans pulled out the injured and dead, laid them by the side of the road, and called out, “Move on!” The attack left Goldberg shaken. “That was the most traumatic experience.”

On December 31, the train arrived at Stalag IVB, a prisoner of war camp for British noncommissioned officers near the town of Mühlberg, halfway between Leipzig and Dresden, east of the Elbe River. Most of the British had been captured in North Africa and Italy and had been there for at least four years. There were also Palestinian Jewish prisoners who fought with the British. “Do they bother you?” Goldberg asked one of the British soldiers. “No they don’t bother me,” he responded. “I have no problem with that.”

Goldberg and his fellow POWs filed by a long table where British soldiers registered them and gave them small postcards to write home. Goldberg wrote to his wife, but she did not receive it until three months later in mid-March 1945. A week after that, she received a notice from the Army that her husband was a POW.

Goldberg’s first meal consisted of watered-down wheat soup, a chunk of bread, and some small potatoes. “That was your ration,” he said, “morning and night.”

If the meal proved despairing, Goldberg’s first shower proved terrifying. “The shower room was like a gas chamber,” he recalled. Fortunately, water flowed from the shower nozzles, not gas. Once a week, the men were entitled to three minutes of hot water and three minutes of cold. “They forced you to take a shower even if you didn’t want to,” he said. The men used the shower to wash their uniforms since the Germans issued them no new ones. For shaving, the men shared a single rough and worn razor. Some of the prisoners possessed scissors for haircuts, otherwise, the men had to rely on the razor.

So began Goldberg’s routine for the next five months. Every morning at 6, he fell out for roll call, where the Germans counted the inmates. He ate two meals a day. “Once in a while, they served oatmeal; that was the best they would give you,” he explained, “and weeds they called vegetables.”

All prisoners were given one hour of mandatory exercise in the yard, rain or shine. The rest of the time was spent in the barracks, where the highest ranking British noncommissioned officer was in charge. Goldberg appreciated the hour of exercise. “If you didn’t keep moving or get enough nutrition you’d die,” he said. When he first arrived in the barracks, he noticed a very skinny GI, sleeping two bunks away, who spent all his time in his bunk. “A couple of days later they carried him out,” he explained. “He had starved to death.”

The barracks proved cold and drafty, with the only warmth coming from a lone stove. “I had a burlap sack for a blanket,” said Goldberg. A separate room contained a long trough with running water that acted as the latrine. “If you went outside to take a leak, other than on your exercise time, you’d get shot.”

The men spent much of their time talking about cooking, food, and the first things they planned to eat after the war. “Food was a big topic of conversation,” recalled Goldberg. “We talked about things like fried chicken and just went through the whole menu.” Goldberg himself craved his mother’s holiday meals. “She made roast beef and special confections only on holidays.”

To get additional nutrition, Goldberg volunteered for work details. “It was very good,” he said. “You got exercise and you got out of the camp.” He either picked potatoes or gathered wood, collecting tree branches to burn in the barracks stove. He used a worn-out pick and his hands to dig for small potatoes. “It took a lot of work to get them out of the ground,” he recalled, “but you got a double ration when you had dinner, enough of a portion so you would survive.”

The POWs were supposed to receive Red Cross packages once a week, but they rarely arrived. “We were lucky to get one package a month,” said Goldberg, “and we had to share it with two or three other guys.” The boxes included canned foods, cheese and crackers, and cigarettes. The German guards often raided the packages or sabotaged the contents. “If it had a can of fish, they’d punch a hole in it,” he explained. “That way, if you escaped, it would spoil.”

As a former track athlete, Goldberg did not smoke, so he traded his cigarettes for food. “The guys who smoked would rather smoke than eat,” he said. Other men illegally gambled for food and for fun. After the 9 PM “lights out” call, when everyone had to be in bed, the gamblers would gather in the latrine and play craps with homemade dice.

The Americans did have one window to the outside world, courtesy of the British: a radio. They had fashioned a radio and followed the war’s progress once a week through BBC broadcasts. They relayed any news to their American buddies. When the Germans learned of the radio, they searched the barracks. “We were told the radio was not in one piece, but held by different guys,” said Goldberg, “so we never knew who had the radio or where it was. It was really very clever.” One day in mid-April someone told Goldberg that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had died on April 12. “I got pretty upset,” he recalled. “I was very sad.”

The men also learned from the radio that American troops, racing east, would halt at the Elbe River, a few miles west of the camp. The POWs knew that if they were going to be liberated it would come from the Russians. Soon, the German guards fled. The next day, on April 23, 1945, the Soviet Red Army arrived and liberated the camp. “The Russians operated it the same way as the Germans,” said Goldberg. “We had the same food, but they didn’t have any guards, and they didn’t care what we did.” By the time Goldberg was liberated, he had lost 45 pounds.

Since none of the POWs knew where they were in Germany, they remained in the camp. After a few days, the Russians brought the POWs to some college dormitories in a small town, but the liberators were focused on killing and capturing Germans and did not feed their recent charges. The POWs resorted to breaking into homes to steal food.

One day, Goldberg and a few of his fellow POWs were scrounging for food when they came upon a farmhouse with some rough-looking Russians armed with submachine guns eating lunch at a long picnic table. Chickens ran around freely in the yard. Using sign language, Goldberg asked them for something to eat. The soldier at the head of the table instructed another soldier to kill one of the chickens. The man opened fire with his submachine gun on one of the chickens but missed. “I think he was the butt of their jokes,” Goldberg recalled. Eventually, someone trapped and killed one of chickens. “It was a little raw,” he remembered, “but it was delicious.”

POWs began leaving in small groups and heading west in search of the U.S. Army. Goldberg took off with a group of about eight soldiers. When they would pass a house, they asked the residents, “Americanski?” The locals would point, and Goldberg’s group would head out in that direction. One farmer invited the POWs into his home for dinner and let them sleep in his barn.

After a few days of hiking, Goldberg’s group came across Americans from an armored unit cleaning their equipment. “It was such an enormous relief and such a great feeling,” he said. “You were home at last.” The POWs looked pretty scraggly, so the armored soldiers took them into town for haircuts from German women barbers. Afterward, Goldberg and his friends were put on Douglas C-47 Skytrain aircraft and flown to Paris.

The plane landed in Garches, a commune in the western section of Paris, where the men were put into an American hospital. While entering the building, Goldberg saw his first American flag in five months. “The flag was a symbol, and it was beautiful to see,” he said. Goldberg snapped to attention and saluted. The men stayed in isolation while the Army arranged their flight back to the United States. They received three meals a day, but Goldberg and his friends simply jumped into the back of the line and repeated. “We got six meals a day.”

After a few days in the hospital, Goldberg came down with hepatitis. The doctors and staff treated him for three months until he was well enough to board a hospital plane on July 4—Independence Day—to fly across the ocean to Fort Dix, New Jersey.

Goldberg recovered at the Chalfonte Hotel and Hadden Hall, a pair of buildings on the Jersey boardwalk. Goldberg remained there for the rest of the year but was given 10-day furloughs to visit with Esther. Finally, on Christmas Day 1945, he left the Army’s care and returned home to Philadelphia. He and Esther moved to a house and had two daughters: Diane, born in 1947, and Shelley, born in 1950. Goldberg returned to the University of Pennsylvania and majored in accounting, then studied to become a certified public accountant.

In 1973, after 30 years of marriage, Esther passed away. Goldberg did not date for two and a half years. “I didn’t think I could find anyone who made me as happy as Esther,” he said. That changed when he met Elaine Fisher, who shared his love for tennis. The two married, and as of 2019 have been together for 37 years.

The war remains with Goldberg. He wrote an article for his local paper about his experiences. He has also attended a number of 106th Infantry Division Association reunions and served as president for three years. He credits others for the association’s success. “The families do all the work,” he said. “Mine was really an honorary position.” He looked forward to the 2019 reunion where he hopes to see the five other Golden Lion veterans who joined him at the 2018 reunion.

Reflecting on his time in uniform, Goldberg expresses chagrin. “We were gung-ho to kill Germans, so it was a major disappointment that we were captured. I would have liked to have seen the war through to the end.”

Frequent contributor Kevin M. Hymel is a historian for the U.S. Army in Arlington, Virginia, and the author of Patton’s Photographs: War As He Saw It. He is also a historian/tour guide for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours, leading tours of General George S. Patton’s battlefields, including locations where the Battle of the Bulge was fought.