By Kevin M. Hymel

Private Armand Lorenzi and his fellow soldiers were advancing through a snowy German forest when enemy machine guns opened fire. It was Lorenzi’s first time in combat. He started scraping a shallow foxhole until he heard German mortars and artillery exploding and rockets screaming in. Then he started digging desperately. “You learn fast,” he recalled. The Germans fired Nebelwerfers, rockets that made a high-pitched scream as they roared to target, earning them the name “Screaming Mimis.” One rocket exploded in the trees. “That’s what scares the life out of you.”

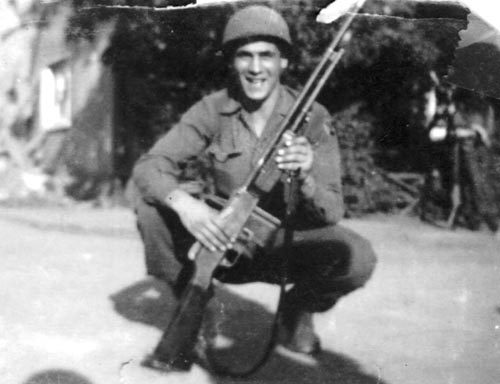

It was during the last months of the war, February 1945, and Lorenzi had just joined Company C of the 302nd Infantry Regiment, part of the 94th Infantry Division in Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.’s Third Army. Lorenzi and his fellow soldiers were trying to wrestle Germany’s Campholz Woods from the stubborn enemy.

In the following weeks, Lorenzi would fight toe to toe with the enemy, battling through forests and towns filled with destroyed German tanks and dead horses. He marched through minefields marked with white tape, constantly worrying about tripping a mine. “Then they send you to that room [in the hospital] where you never go home,” he said. Sometimes German shells, likely manufactured by slave labor, impacted near him without exploding.

A native of Charleroi, Pennsylvania, Lorenzi grew up with his parents, an older brother, and four younger sisters. He was only 15 when he read about the attack on Pearl Harbor in the morning paper. Although only a high school student, he worked as a projectionist at the Hilltop Drive-in Theater until he was drafted in July 1944, five months after he turned 18.

Lorenzi reported to Pittsburgh for his physical. A recruiter asked him what branch he wanted, and he picked the Navy, like his brother. The recruiter stamped NAVY on his card and told him, “We’ll call you in a couple of weeks.” Sure enough, the phone soon rang, and he was invited back to Pittsburgh for another physical. “Bring your clothes with you,” the voice on the line instructed, “because you’re not going home.” After his physical, Lorenzi and all the other recruits were put into the U.S. Army. “Everything broke out in Europe,” he said. “They needed soldiers.”

From Pittsburgh, Lorenzi went to Fort Dix, New Jersey, for basic training, then to Camp Crowder, Missouri, where he was assigned to the Signal Corps. He spent his days climbing poles, stringing wire, and learning to operate a radio. While he trained in Missouri, across the Atlantic Ocean three German armies attacked the American First Army through Belgium and Luxembourg’s Ardennes Forest on December 16, 1944—the Battle of the Bulge. Lorenzi and the other trainees were immediately sent to Louisiana’s Camp Livingston for six weeks of infantry training, including fighting insects and surviving the heat.

After training, Lorenzi and the other replacements headed to New York, but he was able to visit home for a few days on the way. Once in the city, he boarded the SS Louis Pasteur, a French liner, for a six-day journey across the Atlantic. While he never succumbed to sea sickness, his fellow replacements did. “A guy across from me was throwing up in his mess kit,” he recalled.

The Louis Pasteur docked in England at night, and Lorenzi and the others climbed aboard a train. They had to keep the blinds down to prevent light from showing. “I didn’t see anything of England,” he said regretfully. The train deposited the men on a dock, and they boarded another ship bound for Le Harve, France, where they boarded trucks and sped to the front.

Lorenzi’s truck arrived at the front lines at night, and the men piled out. It was cold, and snow blanketed the area. Lorenzi was assigned to a squad in C Company, 302th Infantry Regiment, of Maj. Gen. Harry Malony’s 94th Infantry Division.

The 94th had arrived on the Continent in September 1944 and spent the next four months containing the Germans along France’s Channel ports. During the Battle of the Bulge, it raced across the country and took up positions on the southern flank of Patton’s Third Army. While most of Patton’s other divisions pivoted north to attack the southern border of the Bulge, the 94th was one of the few that remained in place to prevent more Germans from joining the campaign up north.

By the time Lorenzi joined the 94th in February 1945, the Battle of the Bulge had ended, but the Germans were still in the fight. There would be at least three more months of fighting before the war ended. While the division fought specific actions during those months, Lorenzi does not recall the exact towns, hills, or forests where they occurred, but most of his memories coincide with locations and certain aspects of the regiment’s campaigns.

Company C was probably in Pillingerhof, Germany, east of the Moselle River, when Lorenzi joined the unit. On his first patrol, he witnessed the carnage of combat. “The first German I saw had his hand sticking out of the snow.” It was a dead enemy soldier. Behind him Lorenzi saw three American bodies covered by blankets with rifles topped with Army helmets stuck in the snow. “That was pretty scary for an 18-year-old just leaving home.”

One of the first soldiers Lorenzi befriended was a Texan named Leon Stenson, who was older than any of the replacements. Stenson had been fighting with the division for months. “He never smoked or drank,” remembered Lorenzi.

Soon after his introduction to Company C, Lorenzi came under fire for the first time and learned to dig a deeper foxhole. Later, on a predawn patrol with a redheaded sergeant, he crept up to a series of German foxholes, spotted a German, and raised his rifle. “Don’t shoot him,” the sergeant whispered. The shot would have alerted the enemy to their presence. Instead, they made their way back to friendly lines, where they reported the German location. American artillerymen targeted the foxholes and fired a few volleys. The Germans retreated.

Company C’s next task was to take the town of Orscholz on February 19. The men jumped off through a forest at 4 am. When the Germans fired flares into the air, illuminating the area, the men ducked, trying to reduce their profiles. Then the Germans lobbed mortars. “They were more of a concussion than anything,” said Lorenzi.

At night the men climbed aboard some tanks for an attack into Keuchingen. “They smelled of diesel,” Lorenzi recalled. The tanks reached the town, and the men jumped off. Then the tanks roared forward, driving straight into a German ambush. The infantrymen heard the clash. “They got shot up pretty bad.”

The men entered houses, less interested in booze than just finding a place to sleep. They found two old people sleeping in a bed. “We told them to go to the bunker,” said Lorenzi. The Americans preferred German homes to any other place to sleep. In one house, Lorenzi found an Italian .34-caliber pistol while rifling through some drawers. He made it his own.

For meals, Lorenzi enjoyed C-rations, canned meals. Special meals, which were supposed to be treats, had the opposite effect. One of the worst was fresh turkey. “They didn’t even clean it well,” he recalled. “There were some feathers.” Fresh eggs were another disappointment. One day the men were each given two raw eggs. “Cook ‘em the best you can,” the sergeant told them. Lorenzi tried heating his with hot water in his helmet. The result was two soft boiled eggs. “That was the worst.”

Even basic needs resulted in pain. “I drank a lot of bad water,” said Lorenzi. The men had been issued iodine pills to drop into their canteens to purify whatever water they could find. But the pills needed an hour to take effect, and the men were usually too thirsty to wait. The result was misery. “I had diarrhea for a long time,” he recalled. During night marches, Lorenzi and other soldiers would run out of the line to relieve themselves. “Some had it worse than I did.”

One night Lorenzi was standing guard on the line when his stomach started burning. It felt like heartburn. A soldier offered to relieve him from his post, but Lorenzi refused. His guts hurt so much he couldn’t sleep, so he figured it was better to stand guard, explaining, “That was 1945 and I still have it today.”

At the end of February, the division pushed to the Saar River’s west bank near Taben. Lorenzi and five other soldiers clambered aboard a rubber raft, commanded by a lieutenant, to conduct a night reconnaissance. They paddled through the pitch-black night until they could hear German voices and truck motors on the east bank. They were supposed to land, but when the lieutenant heard the noise, he whispered, “That’s enough. Let’s go back.” They turned around.

The next day, February 22, the men received an oral order as they bivouacked in a field: “Patton’s coming!” They scrambled to put their camp in order, but the general never arrived. Patton did visit the division’s headquarters and told General Malony and his staff, “I don’t care if it takes a bushel basket full of dog tags, we’re crossing the river right here.”

In compliance with the general’s orders, the next day before dawn the soldiers of Company C, in groups of six, dragged M-2 assault boats down a twisting road to the river bank near a blown-out bridge south of Taben. Lorenzi remembered the boats not being too heavy. They paddled across the swollen Saar in heavy fog and reached the opposite bank without incident. Then they climbed a 12-foot retaining wall at the water’s edge and hiked up the Höckerburg, which the men called Hocker Hill.

On February 24, the division attacked the town of Beurig on the east side of the Saar River. When advancing against the Germans, the men employed marching fire, attacking while firing their rifles from the hip, a tactic Patton promoted to keep the enemy under cover while the Americans closed in. “I remember we did that a lot,” said Lorenzi.

Entering the town, the Americans fought house to house. Lorenzi and another soldier occupied the second floor of a building. They stacked wheat sacks around a window and fired at enemy soldiers. When German tanks appeared, the other soldier started shaking uncontrollably. Lorenzi told him to lie down. The man was out of the battle, but Lorenzi kept firing from his perch until the Germans were finally driven from the town. The man later recovered and returned to the unit.

A few days later, on March 1, C Company attacked a hill. The Germans countered with rockets, artillery, mortars, and small arms. Lorenzi manned a foxhole, helping another infantryman fire a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). Suddenly, the BAR man started shaking like the soldier had in the building, except this man foamed at the mouth. A lieutenant ran over, pulled the shaking man away, and told Lorenzi he was now a BAR man.

As the new BAR man, Lorenzi often went on patrols with his lieutenant. Lorenzi’s new weapon weighed 22 pounds fully loaded and fired .30-06 rounds. He also had to carry extra clips, “and I only weighed 140 pounds soaking wet,” he said. It was as the BAR man that Lorenzi met Private Nick Laudato, a Pittsburgh native, who helped him with his new weapon. Lorenzi often traded the BAR with Laudato, who gave him the BAR ammunition. “He was a nice fellow,” Lorenzi said of the man who became his best friend.

On one patrol the lieutenant sprinted up a steep hill while Lorenzi, lugging his BAR, and the other soldiers tried to keep up. When they finally reached the lieutenant near the top he told them, rather impressed with himself, “I’m a little older than you fellas.” But Lorenzi was unimpressed. “He was only carrying a carbine,” he recalled, which weighed six pounds fully loaded.

The fight for the hill seesawed back and forth for three days, with the Germans counterattacking every one of the company’s attempts to secure the summit. During one counterattack the Germans broke through the line, and Lorenzi and his comrades ran for the rear. As they charged into a wood, a sergeant yelled out, “Get out of there! There’s mines in there!” The men froze and walked back out, not tripping any mines as they went.

At one point the Americans captured several Germans. “I’ve seen a lot of German prisoners,” said Lorenzi. The Americans would line up to search the prisoners for souvenirs, especially P-36 pistols and Lugers, but they never found any. “If we had found any guns,” admitted Lorenzi, “the lieutenant would take them from you anyway.” Officers always had dibs on souvenirs. Although the Americans captured both regular Wehrmacht and SS mountain troops, Lorenzi could not tell the difference. He did notice one thing about the enemy: “They dressed pretty snappy.”

The division spent the rest of March fighting for the small town of Schömerich and, more than 100 miles to the east, Ludwigshafen, where tankers of the 12th Armored Division joined them to crush the last remnants of the German Army. Ludwigshafen was the division’s last battle.

After two straight months of fighting, the 94th was placed in reserve. The troops were trucked to Baumholder, a German training center. But the break was short-lived. Two days later, the division was reassigned to Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ First Army, which was trying to close the Ruhr Pocket. The men reboarded trucks for the 175-mile drive north. When they finally crossed the Rhine River on April 22, enemy shells were still exploding in the water.

Lorenzi crossed the Rhine by walking over a pontoon bridge. “The bridge was not too wide,” he remembered. “There was just enough room for trucks to get across.” Once across, he and the rest of the 94th took up occupation duties in Düsseldorf. Lorenzi was assigned to the military police to help keep order. Their main task was preventing American soldiers from stealing. “Any time someone was breaking into a building to steal wine from its cellar,” he remembered, “we were called.”

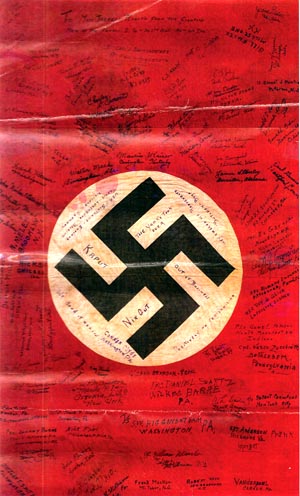

One day a lieutenant walked up to Lorenzi and told him that the war was over. It was May 8, 1945, and the German high command had officially surrendered to the Allies. What was left of Europe at the end of six years of war was at peace. To celebrate the victory, Staff Sergeant Al Deyer passed a Nazi flag around to everyone in C Company to sign. Lorenzi signed his name and hometown.

The 94th took up occupation duties in Czechoslovakia. While many occupying Americans found the Czechs worse than the Germans, Lorenzi found them accommodating. “They were nice to us,” he said.

Getting to Czechoslovakia, however, proved difficult. Lorenzi’s company took off in a convoy of trucks for the ride across Germany. Along the way his truck broke down in a German forest, but his lieutenant said, “I’ll send another truck back for you.”

The convoy headed southeast while Lorenzi and his men waited … and waited. Hours turned into days. “We were there for a week,” he recalled, “and he never showed up.” The men scrounged for food and hunted for deer with their M-1 Garand rifles. They finally decided to walk to the next town. When they arrived, an angry lieutenant gave them hell. “Where were you?” he demanded. Lorenzi explained the situation, and the officer calmed down. The men eventually located their company.

Lorenzi and his comrades enjoyed occupation duty. They skied, rode horses, and drank. Living close to a brewery, the men rolled a barrel of dark beer out of the building almost daily. Once they drained it, they rolled the empty barrel out to the road. For other entertainment, the men sneaked into a nearby displaced persons camp to meet the women inside. “They must have been Polish,” recalled Lorenzi.

After the easy duty in Czechoslovakia, Lorenzi boarded a 40 & 8 train for a slow ride west across Europe. The simple boxcars, with no seats, contained a bucket filled with sand and a can of gasoline. To keep the car warm, the men had to pour gas into the bucket and light it. The train was so slow the men often jumped off to relieve themselves, then jumped back on.

After the lengthy trip, the train arrived at Camp Lucky Strike in La Havre, France. While Lorenzi waited for transport home, he met a soldier who had been a teacher back in the United States. He was working on a song that mimicked The Merry Macs 1944 number one hit song, “Mairzy Doats”:

“Eighty-eights and hand grenades and lots of screaming mimis.

I’d dive for my hole too, wouldn’t you?

If the words sound queer and funnier to your ear,

Why don’t you come over and try it.”

Although the soldier never finished the song, Lorenzi enjoyed it so much he committed it to memory.

Soon, Lorenzi boarded a Victory ship for his trip home. The journey was almost as bad as the combat. Stormy weather stirred up giant swells that violently tossed the ship. One day he was walking to the showers when the ship went up against a wave, tilting it almost vertically. Terrified, he ran back to his bunk. “I grabbed my life preserver and never took it off,” he said.

After eight days on the water, the Victory ship pulled into port at New York City. As Lorenzi headed down the gangplank, he saw MPs standing on the dock, checking debarking soldiers for weapons. He quickly dug his Italian pistol out of his duffel bag and stuffed it under his belt. He passed inspection without losing it.

The soldiers were brought to Camp Shanks, where Lorenzi called his parents. He then took a bus to New Jersey, where he met his father and brother, home from the Pacific. They piled into a car and drove home. When he arrived, Lorenzi’s mother wasn’t there, but when she did arrive she cried. “She was just so happy to see me,” he said.

For about a month Lorenzi and his brother spent their nights drinking, getting the war out of their systems. Then their father told them, “It’s about time you boys got back to work.” And that is just what they did.

Lorenzi returned to his projectionist job at the theater and worked in the profession for the next 20 years. He then took a security guard job at the local steel mill for 35 years until he retired in 2001.

Lorenzi met Patricia McFall through her stepfather at a club the two frequented. He married her, but they divorced after 32 years. He met another woman and married her for seven years, but she passed away. Today, he shares his life with Mary Lou Lachman, whom he calls, “a very good woman.” They enjoy dancing together.

In 2006, Lorenzi received a print of the Nazi flag he had signed on the last day of the war. The child of a woman who received it after the war sent it to him in an effort for all C Company veterans to have a copy. As of 2018, Lorenzi still had the Italian pistol he snuck off the ship, though he has never fired it for one simple reason: “I took the firing pin out of it.”

Since the war Lorenzi has attended a number of 94th Infantry Division reunions. He has also gone to the annual D-Day reenactments at Conneaut, Ohio. He has visited Normandy, France, and Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, but has never returned to the forests and small towns of Germany where he fought. He still remembers his introduction to combat like it was yesterday. “I can still remember seeing that [dead] German soldier.”

Kevin M. Hymel is a historian for the U.S. Air Force Medical Service History Office at Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas. He is also the author of Patton’s Photographs: War As He Saw It and leads tours of General George S. Patton’s battlefields for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours.