By Carole Butcher

On a warm morning in July 1861, the Union Army marched forth with bands playing and regimental flags flying. Spirits were high. In two weeks or so, the thinking went, the war would be over. The men were heading toward Manassas, Virginia, to confront the Confederates along the banks of Bull Run creek. Marching in the Union Army that day was Private Franklin Thomas, who admitted having misgivings about the coming battle. “In gay spirits the army moved forward,” Thomas wrote, “the air resounding with the music of regimental bands, the patriotic songs of the soldiers. I felt strangely out of harmony with the wild, joyous spirit which pervaded the troops. I thought that many, very many of those enthusiastic men who appeared to meet the enemy, would never return to relate the success or defeat of that splendid army.”

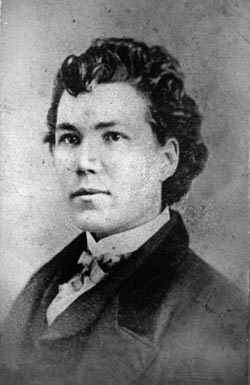

On the Confederate side, Lieutenant Harry T. Buford had no such reservations. “I was never in better health and spirit than on that bright summer morning,” Buford wrote, “when I left Richmond for the purpose of joining the forces of the Confederacy in the face of the enemy; and the nearer we approached our destination, the more elated did I become at the prospect before me of being able to prove myself as good a fighter as any of the gallant men who had taken up arms in behalf of the cause of Southern independence.”

Social Constraints in the 1860s

One Federal soldier and one Confederate, one private and one officer, one on foot and one riding a fine steed—it would seem that they had very little in common. But they did share one important fact: they were both women.

Women of the 1860s were restrained by social constraints. Gender roles were clearly defined. The man’s sphere was largely outside the home, providing for the family. A woman’s place, on the other hand, was in the home. If a woman did venture outside the home, employment opportunities were extremely limited and poorly paid. Society decreed that women should dress and behave demurely and properly. They should be subservient to their fathers and, later, to their husbands. They should be good wives and mothers. And under no circumstances should they run off and join the army.

When the Civil War broke out, some women enviously watched their men don uniforms, take up arms, and march off to defend a noble cause. Sarah Morgan of Louisiana wrote: “Oh! If I was only a man! Then I would don breeches and slay them without will! If some few women were in the ranks, they could set the men an example they would not blush to follow!” But most women remained in the roles assigned to them by society, even as they considered how best to support the war effort. They rolled bandages, raised money and collected supplies to send to the soldiers. They did laundry and nursed the wounded.

Women Soldiers in the Civil War

Some more daring women were motivated to take a different course of action. Mary Livermore of the United States Sanitary Commission wrote in 1888: “Someone has stated the number of women soldiers known to the service as a little less than four hundred. I cannot vouch for the correctness of this estimate, but I am convinced that a larger number of women disguised themselves and enlisted in the service, for one cause or other, than was dreamed of.”

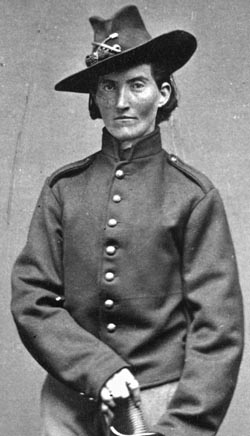

Women were motivated by a variety of factors. Some women enlisted in order to stay with their husbands. Some were attracted by a paycheck that was far more generous than any salary a woman could earn. Other women felt the same patriotic fervor that motivated some men. And yet others longed for the adventure that was denied to them as women. Sarah Edmunds wrote after the war, “The privations and danger of life in the army were thrilling and stoked my spirit of adventure.”

Access to the military was surprisingly easy. Some women even tried to enlist without disguising themselves. The women of LaGrange, Georgia, organized a militia they named the “Nancy Harts,” after a Revolutionary War heroine. They were ready to fight, and regularly held shooting practice. Every capable woman of LaGrange enlisted in the Nancy Harts. Their offer to join the fight, however, was rejected by the Confederate secretary of war. Other women on both sides who attempted to formally enlist openly as women received similar responses.

Recruiting at 90 Per Hour

Determined women resorted to disguising themselves. This tactic was far more successful; enlistment physicals were cursory at best. One doctor reported evaluating 90 recruits per hour. Lieutenant Buford (Loreta Janeta Velazquez) reported that her enlistment physical consisted entirely of a handshake. As the need for new recruits grew, enlistees who had been rejected the first time around were accepted on the second try. Sarah Edmonds, disguised as Frank Thompson, was rejected on her first try for being too short and delicate. But when the military returned looking for more recruits, she was accepted with no difficulty. Recruiters were generally satisfied if an enlistee was reasonably tall, had a functioning trigger finger, and sported enough teeth in his mouth to tear open a powder cartridge—the bare minimum of skills needed for a soldier.

Societal constraints actually benefited women who wanted to disguise themselves and enlist. Upper-class women of the time wore voluminous gowns with hoops and numerous petticoats. Lower-class women wore less extravagant clothing, but nonetheless dressed in floor-length skirts. Almost all women wore their hair long. It was scandalous for a woman to cut her hair short and appear in public dressed in trousers. Therefore, anyone with short hair dressed in trousers was automatically assumed to be a man. In addition, many young boys already were serving in the military. If a soldier was slight of build and had a smooth face, he was most often accepted as a boy who was still too young to grow a beard.

Women Soldiers Were an Open Secret

In 1862, Malinda Pritchard cut her hair and put on men’s clothing so that she could join her husband, who had enlisted in the Confederate Army. She easily passed herself off as her husband’s younger brother Sam. When her husband tired of military life, he rolled in poison oak to receive a medical discharge. Sam confessed to being a woman in order to be discharged with her him. Until that time, she had successfully maintained her disguise as a man.

It was an open secret at the time that women were serving as soldiers. Newspapers reported numerous incidents of women serving in the army. On April 13, 1862, the Dubuque Herald reported, “The Troy Budget learns from private correspondence that one of the companies on the Potomac has been for a short time in command of a good-looking lieutenant, who turns out to be a lady from that city.” On June 5, 1861, the Savannah Republican printed a story about Mary W. Dennis, a first lieutenant in a Minnesota regiment. The Daily Chronicle and Sentinel of Augusta, Georgia, reported on August 4, 1861, that a Mrs. Curtis, of the 2nd New York Regiment, had been captured at Falls Church, Virginia. The Savannah Republican also printed the story, adding that suitable lodgings had been provided for her in a private house.

From the Charleston Mercury, on January 16, 1862, came the report: “A young widow woman named McDonald was discharged from Col. Boone’s Regiment, at Paraquet Springs, Kentucky last week, where she had been serving as a private, dressed in regimentals, for some time. This was her second offence, she having once before been discharged from a regiment.” The Austin State Gazette repeated the story on February 22, 1862, adding, “The distress among the poor at the North is so great that their papers give account of women, dressed in men’s clothes, enlisting as privates in the army.” On May 15, 1862, the Augusta Daily Chronicle and Sentinel published a story about a woman named Blaylow who had joined the army to be with her husband. When Private Blaylow was discharged, the newspaper noted: “Another soldier applied for discharge, stating that he (or she) was the lawful wife of Blaylow. It appears that when Blaylow was drafted his wife cut her hair off, put on men’s clothing and went with him into the camps and enlisted for the war.”

Fitting in With The Unit

Women sometimes engaged in traditional masculine activities such as drinking and card playing to bolster their identities as men. Some even went as far as courting other women. Even such offhand habits as spitting, smoking and swearing could reinforce the impression that a female soldier was, indeed, a man. But alcohol could prove hazardous to women who were attempting to maintain a disguise. A woman known as Canadian Lou “betrayed herself while intoxicated in Memphis.” When she drank and became unruly, she wound up in jail and was recognized as a woman by someone who knew her. Loreta Velazquez, a.k.a. Lieutenant Harry T. Buford, refused to drink. She wrote that she had “vowed to establish a reputation for temperance” lest she reveal herself while drunk.

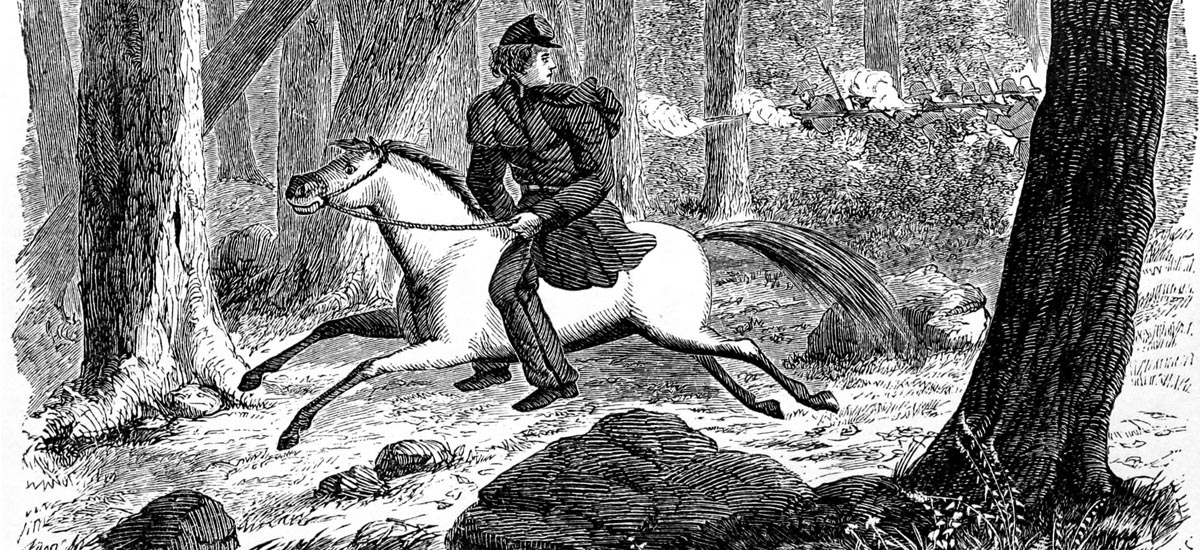

Spitting, swearing and drinking were all well and good, but the true test of a soldier was combat. Martha Lindley wrote after the war: “I did the best I could in the service of my country. Although I am only a woman, I think I can say without egotism that there were worse soldiers than I in the service.” Sarah Edmonds said she often sat down and “wept bitter tears of disappointment and sorrow, and then, with a heavy heart and aching limbs, I returned to camp.” Jennie Hodges participated in over 40 battles, including the siege of Vicksburg. She was remembered by comrades as a brave and capable soldier.

Women who enlisted in order to remain with their husbands faced an additional fear in combat: that of witnessing the death of a loved one. Amy Clark fought beside her husband in the Confederate Army. When he was killed, she buried him herself. She continued serving until she was wounded and her true gender was discovered. Frances Clayton witnessed her husband’s death from mere yards away. She stepped over his body and maintained her place in her unit’s formation. These women had joined the army to be with a loved one, but they became true soldiers and veterans during the heat of combat.

A Hard Secret to Maintain

Female soldiers were discovered in a variety of ways. In October 1861, 19-year-old John Williams was discharged on the grounds that he was “proved to be a woman.” It is unclear just how Williams was discovered. Charles Freeman, a private with the 52nd Ohio Infantry, was admitted to the hospital with a fever, whereupon the hospital staff discovered the truth: Charles Freeman was really Mary Scaberry. It was almost impossible for a woman to maintain her secret identity if she was hospitalized. Mary Galloway was wounded and attended to by none other than Clara Barton, who naturally discovered Galloway’s secret.

Some women were discovered when they were captured. Frances Hook was captured near Florence, Alabama. Her captors, realizing she was a woman, quickly exchanged her. Florina Budwin was held at the infamous Andersonville Prison with her husband. After her husband died there, she was transferred to another prison. A doctor discovered her true identity when she became ill. She died shortly afterward.

On occasion, a woman’s identity was discovered only after her death. When Brig. Gen. William Hays gave a report about the burial of the dead after the Battle of Gettysburg, he included mention of the burial of a “female (private) in rebel uniform.” Hays reported that, rather than seizing the enemy battle flag, Union soldiers used it as the woman’s burial shroud. Some women had to wait even longer to be recognized. In 1934, a Tennessee man was digging a flower bed when he uncovered the remains of Civil War soldiers near Shiloh. Upon examination, one of the sets of remains was discovered to be those of a woman.

Information about women soldiers in the Civil War sometimes came to light in their obituaries. Elizabeth Niles died at age 92. Her obituary revealed that she had cropped her hair and fought beside her husband throughout the war. Elizabeth Finneran’s obituary detailed her military service, giving her the recognition in death that she did not receive in life.

Returning Home

Most female soldiers returned to their homes and traditional gender roles after the war. But not all women went back to the lives they had left behind. At least one continued to live her life as a man. Jennie Hodges served with the 95th Illinois Infantry as Albert Cashier. She lived the rest of her life as Albert. She worked as a janitor, handyman and town lamplighter, and applied for and received a pension based on her military service. Her true identity was only discovered when she became ill and was hospitalized. Her old comrades came to visit her and confirmed that she had been an able soldier. When she died in 1915, she was buried with full military honors. Her tombstone gives her name as both Jennie Hodges and Albert Cashier. It also adds: “Co. G 95 Ill. Inf.” She would have been proudest of the unit designation.

Women fought for a variety of reasons. Some wished to stay by the side of a loved one. Others felt the same patriotic zeal as men and wished to defend their country. Some women were attracted by the pay, others by a sense of adventure. But though no one knows exactly how many women pursued a military career in the Civil War—the exact number will never be known—there is no doubt that many women turned their backs on traditional 19th-Century feminine roles to take up arms as a soldier. Few, it should be noted, disgraced themselves in battle.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments