By Mark Carlson

To die for personal honor is a long-vanished custom of the pre-industrial age. But 200 years ago it still held great meaning for men, particularly in politics and the military. Many men of that period would eagerly face death to defend their honor. Commodore Stephen Decatur was such a man. A veteran of the Barbary Wars and the War of 1812, he was a naval officer whose fame as comparable to that of later American heroes such as pilot Charles Lindbergh and astronaut Neil Armstrong.

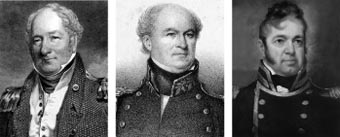

Tall and handsome, the Philadelphia native had first gained fame in the nascent U.S. Navy by leading the small volunteer force that boarded and burned the captured frigate Philadelphia in Tripoli harbor in 1804. From that day his fame grew, matched only by his unquenchable thirst for glory. In March 1820 Decatur died at the hands of a fellow naval officer in a duel in which he participated to preserve his honor. The duel that felled Decatur might have been a conspiracy to commit murder by those who helped arrange it.

The origins of that day go back to June 1807, during the calm between the first Barbary Wars and the War of 1812. When a squadron of Royal Navy warships rode at anchor just off Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia, several men deserted and made their way into the city. Some of them took the opportunity to enlist in the U.S. Navy. This led directly to the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair.

The frigate USS Chesapeake was being prepared for an extended cruise to the Mediterranean under Commodore James Barron, a veteran of the Barbary Wars. The tall, aristocratic Virginian had served with his father as a midshipman during the American Revolution. Although he joined the Navy in 1797, most of his time at sea had been in merchant ships. The U.S. Navy had commissioned the 38-gun Chesapeake at the Gosport Navy Yard in 1800. She was one of the original six frigates that Congress authorized via the Naval Act of 1794.

As preparations for the cruise moved forward, Barron was informed by U.S. Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith that a number of men suspected of being deserters from Royal Navy warships had signed on to the crew of the Chesapeake. Smith asked Barron to find them and determine their status. Barron spoke with three of these men. He then informed Smith in writing that he was satisfied that, even though they were deserters, they also were American citizens. This ended the matter as far as the Barron was concerned; however, the British had other ideas.

Before leaving port, the Chesapeake was in disarray. The crew had piled lumber, crates, and provisions on the upper deck and many guns were not mounted. The disarray on the decks seemed not to bother Barron. On the morning of June 21, 1807, the frigate set sail for the Mediterranean. She cleared Hampton Roads and sailed past a British squadron stationed off Lynnhaven Bay. This was during the Napoleonic Wars, and the British squadron was blockading two French ships in the Cheseapeake Bay.

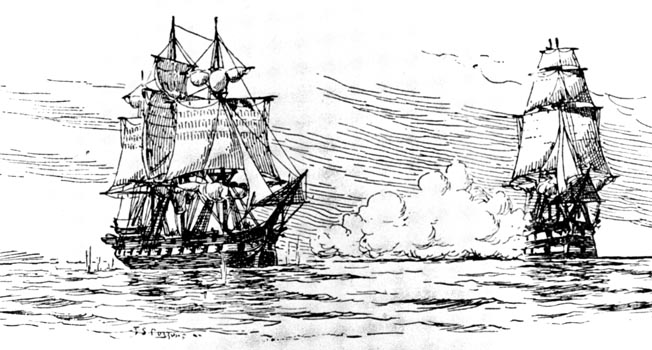

The Royal Navy squadron included the 74-gun Triumph and the 50-gun Leopard. They raised anchor and headed out to sea. The Americans took note but read nothing into it until they were well out to sea. At 3:27 pm the Leopard came to within 60 yards of the Chesapeake and called via speaking trumpet that she had a message for Barron. The commodore agreed to let a boat come over and ordered the Chesapeake hove to. Even in peacetime, a prudent commander would call his crew to action when being approached by a warship of another nation. Barron felt this was unnecessary and waited to greet the British representative. The Royal Navy lieutenant handed Barron a letter from the admiral in command of the British squadron at the North American Station. The admiral demanded the return of every Royal Navy deserter onboard Chesapeake. Barron fumed at this insolence and flatly refused. Again setting sail, Barron saw the Leopard approaching his vessel. Another hailing call was made, but before Barron could reply the larger ship fired a shot across his bow. This was clearly a provocation. Barron was in a tight fix. He had not alerted the crew nor made any moves toward getting his guns ready for action.

Suddenly, the Leopard unleashed a massive broadside into the smaller American ship, sending splinters and hot iron tearing across the decks. The Chesapeake’s unprepared crew suffered a large number of casualties. Pandemonium ensued as the Americans scrambled to load and fire their guns. The materials stacked around the upper deck hampered their ability to operate quickly and efficiently. “For God’s sake, to fire one gun for the honor of the flag I must strike!” roared Barron, who had been wounded in the leg.

One officer managed to get a coal from the galley stove and used it to fire a single gun. Barron had no choice but to surrender. With dozens of men bleeding and dying on the decks he watched impotently as two boats loaded with officers and armed men boarded his ship. They found their four deserters and removed them from the ship. Then, the Leopard sailed off. Afterward the battered Chesapeake, with dead and dying men strewn across its bloody decks, limped back to Norfolk.

The first U.S. Navy officer to board the crippled frigate the following day was Decatur, the commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yard. He was horrified by the destruction and chaos, as well as downright angry. But unlike the rest of the nation, which was incensed with the unwarranted attack by the British, Decatur reserved his rancor for one man: James Barron. Decatur believed that Barron had surrendered to the British without a fight. In his mind, the act was simply unforgivable.

Decatur was appointed to the four-man court-martial board convened after a board of inquiry decided Barron should be held accountable for the disaster. Barron faced death if convicted. Decatur did not want to serve on the court-martial board because he believed he could not be objective.

Decatur had known Barron since 1798 when as a young midshipman on the frigate USS United States during the so-called Quasi-War with France, he had served under Third Lieutenant Barron. Decatur, who was 10 years younger than Barron, initially had great respect and admiration for Barron.

Over time Decatur’s opinion of Barron underwent a radical change. “He is an excellent seaman, but he is no soldier,” Decatur said. Barron simply did not measure up to Decatur’s high standards of courage and leadership.

If Barron, who would have to face the court-martial board, hoped for any leniency from his old protegé, he would be sorely disappointed. Decatur glared at his old mentor with uncompromising hostility.

On June 22, 1807, the board found Barron guilty on all charges. Yet because of his long service and exemplary past conduct, he was suspended from the U.S. Navy for a period of five years without pay. Navy rules stated that after five years, effective January 1813, he would be permitted to reapply for his commission.

By that time, the United States was at war with Great Britain. The War of 1812 offered U.S. Navy officers many opportunities for distinction. Like many others, Decatur hungered for fame and glory, which he achieved quickly in one of the first naval victories of the war. On October 25, 1812, he crippled and captured the British frigate HMS Macedonian in an engagement in the Atlantic Ocean 500 miles south of the Azores.

Barron returned to the United States in December 1818. During the war, while his fellow officers were actively fighting the Royal Navy, Barron was conspicuously absent. He remained in Denmark where he occasionally commanded British-registered merchant ships. It was also alleged that he had made disparaging remarks about the U.S. Navy to a British officer in Brazil. Many officers in the U.S. Navy considered this tantamount to treason.

Although Barron submitted an inquiry about his commission to the Secretary of the Navy in 1813, he did not reapply for it at that time. When he did try to regain his commission in 1818, he found no support for it. Many of the officers in the service opposed it. The most vocal of these was Decatur.

Barron was at first confused, hurt, and insulted. He was incensed when he learned that Decatur had said he could “insult Barron with impunity.” In the vernacular of the day, the expression meant that Barron lacked honor and was too cowardly to take insult. For Barron, who had been enduring scorn ever since his court-martial, Decatur’s dig was unbearable.

He began by writing peevish letters to Decatur outlining his grievances. Never a combative man, as the affair with the Leopard indicated, he only seemed to want Decatur to acknowledge the insult and apologize. But these were things that the proud Decatur would not do. This continued until early the fall of 1819 when Barron’s letter writing stopped.

At that point, Decatur considered the matter done. Then, another letter arrived just before the end of the year. Barron’s earlier correspondence had been mostly self-serving and querulous. But the new letter was more challenging, almost as if someone else had written it. What had precipitated the sudden change?

Americans had learned that year that Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry had died on August 23 of yellow fever while on duty in South America. Although seemingly unconnected with the Barron-Decatur dispute, it may well have been the catalyst that led directly to the duel.

Captain Jesse Elliott, who was well known in the U.S. Navy for his confrontational behavior, had been second in command under Commodore Perry during the battle for Lake Erie in September 1813. Perry, himself a firebrand like his close friend Decatur, was angered at Elliott’s failure to carry out Perry’s orders to attack the British ships. He pressed charges of insubordination and cowardice against Elliott, but the demands of the war compelled the U.S. Navy to defer the matter until later.

Perry kept detailed records of the incident and never stopped his campaign to see Elliott court-martialed. The matter had not been resolved when Perry was sent to Venezuela on a diplomatic mission. Perry had handed his documents over to Decatur for safekeeping in case of his death.

Elliott approached Barron in late 1819 and offered his help. He had been a midshipman aboard USS Chesapeake in 1807 and had spoken in Barron’s defense at the court-martial. His involvement in the dispute coincided with Perry’s death. He knew that Perry had given his papers to Decatur. Perry was no longer a threat; Decatur was now the enemy. A man of much stronger will and determination than the complaining Barron, Elliott was almost certainly influencing him in the spring of 1820.

Although exasperated, Decatur told Barron that he accepted his challenge. As time passed, though, Decatur was unable to find a suitable officer to serve as his second. Commodores John Rodgers and David Porter, both of whom served on the Navy Board with Decatur, refused on the grounds that the duel was pointless.

Decatur was walking home from the Navy Department one day in March 1820 when a carriage stopped in front of him. Commodore William Bainbridge emerged from the carriage with a broad smile. Reaching for Decatur’s hand to give it a warm shake, he said, “Decatur, I’ve been a fool! I hope you will forgive me.”

This was totally unexpected and with good reason. In the early months of 1815, U.S. President James Madison had sent two strong squadrons of warships to the Mediterranean Sea to force the Barbary States into favorable treaty terms. Overall command was given to Commodore William Bainbridge, a hero of the War of 1812 and the captain of the Philadelphia when she was captured by the Tripolitans.

Bainbridge had every reason to want success and revenge. His subordinate, in command of the first squadron, was Decatur, who was to leave for the Mediterranean Sea a month earlier than Bainbridge. Eager and audacious as ever, Decatur confronted, blockaded, and threatened the four Barbary States and in less than two weeks had achieved every goal of the mission.

When Bainbridge arrived with his ships, he found that Decatur had done the job for him. A proud man, Bainbridge was suddenly irrelevant. He never forgave Decatur for stealing his glory. Decatur was not cruel or mean; he simply never gave a thought to Bainbridge’s feelings. Decatur had made a bitter enemy. When Bainbridge encountered Decatur in the halls of the Navy Department over the course of the next five years, he never uttered a single word to him.

Although he was confused by Bainbridge’s behavior, Decatur invited him to his home. At some point during their conversation, the subject of Decatur’s duel with Barron arose. Bainbridge offered to act as Decatur’s second. Decatur, who was relieved by the offer, gladly accepted it. Bainbridge set off to handle the duties of the second. He subsequently contacted Elliott and Barron to arrange the time, place, and other details.

For anyone other than Decatur, the sudden arrival and friendliness of someone who had spent five years in bitter hostility would seem highly suspicious. But Decatur, who was an honorable man, tended to attribute these qualities to others. He was too relieved to have a suitable second to question Bainbridge’s odd turnabout. But it is very likely Bainbridge had already been in contact with Elliott.

The seconds established the details of the duel. They selected a sloping field in Bladensburg, Maryland, that had long served as a dueling ground. Since dueling was technically illegal, it was better not to conduct it in the nation’s capital.

The duelists, who would use flintlock pistols, were told to arrive at 9 am on March 22, 1820. Some of the specifics established for the duel were unusual. Instead of having each man walk 10 to 12 paces, as was ordinarily done, and then turn, aim, and fire, Decatur and Barron would stand facing one another at eight paces with aimed pistols. Firing at each other from eight paces was almost sure to produce serious, and perhaps even fatal, wounds. This was likely to be the outcome even with the smoothbore pistols of the day.

Barron, who was over 50 and nearsighted, had asked for this concession to assure that he had an equal chance against the younger and steadier Decatur. Bainbridge was to count “one, two, three.” The duelists were to fire after one and before three.

The duelists, both of whom wore civilian clothes, arrived on time at the Bladensburg field. Each had come with his second, but Decatur also had the support of Commodores Rodgers and Porter. Barron appeared nervous and even reluctant, but Elliott was at his side, offering support and encouragement.

The two men faced each another. Decatur had told Rodgers he had no wish to kill Barron. At Bainbridge’s order to present, each man cocked and raised his pistol and took aim at his opponent’s hip. “I hope that when we meet in another world we will be better friends than we have in this,” Barron said.

“I have never been your enemy, sir,” replied Decatur.

Bainbridge began counting. Both guns discharged. Each barrel emitted a spurt of yellow flame followed by a cloud of white smoke. Barron grunted and slid to the ground; Decatur swayed on his feet. The color drained from his face as a bright red stain spread over his groin. “Oh, Lord,” Decatur mumbled. “I am a dead man.” He too fell to the ground.

Elliott ran for the carriage. He had almost reached it when Porter caught up to him and shouted at him to stop. “How do things fare?” asked Elliott.

Infuriated by Elliott’s flight, Porter said, “Go back and do your duty for your wounded friend!” Elliott never returned.

Meanwhile, Decatur was carried to his carriage. As he was laid inside, Baron said, “God bless you, Decatur.”

“Farewell, Barron,” Decatur replied in a weak voice.

Decatur died in his home later that day. His death plunged the nation into mourning.

Was it a legitimate duel or a conspiracy to kill Decatur? One point stands out. When Barron and Decatur had their verbal exchange just before firing, it was a clear sign that each had forgiven the other. That was the moment that either second should have spoken up and called a halt, since the duel was no longer necessary. But neither man did so. They failed to protect the men they had sworn to represent. The only plausible reason is that each had a motive for wanting Decatur dead.

Bainbridge wanted revenge, while Elliott sought to remove the final threat to his naval career embodied in the documents that Decatur had in his possession. Despite his unerring skill in naval combat and shrewd dealings with the Navy, Decatur was surprisingly obtuse in not realizing that the two seconds were his enemies.

As for Bainbridge, he had a strong desire to be remembered in a favorable light. He kept extensive letters and papers. Yet on his deathbed, he ordered his daughter to burn all his personal correspondence. This makes absolutely no sense; that is, unless those documents contained correspondence with Elliott and Barron detailing how they plotted to force Decatur into a duel.

Although these theories are now impossible to prove, the circumstantial evidence is compelling. All three officers had long and distinguished careers in the U.S. Navy. Decatur is revered to this day, while Barron is forever tainted as the man who killed a beloved naval hero. He might just have been a pawn in an even greater infamy.