By Duane Schultz

For the thousands of Allied soldiers who had fought and suffered for so long in the shadow of the abbey of Monte Cassino, Tuesday morning, February 15, 1944, was a time of joy and celebration. The men hated and feared the abbey, standing four stories tall atop the 1,700-foot mountain above them. The troops knew that it was finally going to be destroyed, and they were more than eager to see it happen.

“Like a lion it crouched,” wrote American Lieutenant Harold Bond, describing the abbey 20 years later, “dominating all approaches, watching every move made by the armies below.” Everyone was convinced that German soldiers occupied the abbey as an observation post to track the Allies’ movements in the valley below and thus direct artillery fire on them. Clare Cunningham, a 21-year-old lieutenant from Michigan, said, “It seemed like we were under observation all the time. They were just looking down on us all day long. They knew every move we were making.”

Thirty years after the war, the passion, fury, and hatred of the abbey remained with British Lieutenant Bruce Foster when asked what he thought about the destruction in 1944. “Can you imagine,” he said in reply, “what it’s like to see a person’s head explode in a great flash of grey brains and red hair? Can you imagine what it is like when that head belonged to your sister’s fiancé? I knew why it happened; I was positive it was because some bloody … Jerry was up there in that bloody … monastery directing the fire that killed Dickie, and I know that still.”

No place below the abbey was considered safe from enemy fire. Sergeant Evans of the British Army wrote that the abbey “was malignant. It was evil somehow. I don’t know how a monastery can be evil, but it was looking at you. It was all-devouring…. It had a terrible hold on us soldiers…. It just had to be bombed.” According to another soldier, Fred Majdalany, “That brooding monastery ate into our souls.”

On the morning of the bombing, hundreds of rear-echelon troops and dozens of war reporters showed up to watch. War correspondent John Lardner wrote in Newsweek magazine that it was “the most widely advertised single bombing in history.”

“A holiday atmosphere prevailed among the soldiers,” historians David Hapgood and David Richardson wrote. “For almost all the men of the [American] Fifth Army, this Tuesday was a rare day off from the war. Soldiers … scrambled for positions from which they could watch what was to come. Some stood on stone walls, others climbed trees for a better view. Observers—soldiers, generals, reporters—were scattered over the slopes of Monte Trocchio, the hill that faced Monte Cassino, three miles across the valley. A group of doctors and nurses had driven up in jeeps from the hospital in Naples. They settled themselves on Monte Trocchio with a picnic of K-rations, prepared to enjoy the show.”

The first bombers appeared in the clear blue sky at 9:28 that morning. For approximately four hours, until 1:33 that afternoon, wave after wave of bombers, some 256 in all, dropped 453 tons of bombs on the abbey. Artillery pounded the target as well. The New York Timesdescribed it as the “worst aerial and artillery onslaught ever directed against a single building.”

John Blythe, a New Zealand officer, wrote that as the planes came in “the smoke began to rise, the vapor trails grew and merged, and the sun was blotted out and the whole sky turned gray.” With every new explosion and burst of artillery fire and flame erupting from the abbey, the cheering among the observers grew louder.

Martha Gellhorn, an American war reporter, wrote that she “watched the planes come in and drop their loads and saw the monastery turned into a muddle of dust and heard the big bangs and was absolutely delighted and cheered like all the other fools.”

When it was over, the rubble was spread over the seven-acre site with only a few jagged pieces of wall still standing. But it quickly became the site of condemnation and controversy over the necessity of destroying it. Ultimately, though the Allies did not believe it at the time, the Germans had the propaganda advantage: no German soldiers had ever been stationed in the abbey.

The Germans had forbidden their troops to enter it in order to protect it from Allied destruction. Also, they had not needed to use that vantage point to observe Allied troop movements. The Germans had built ample observation and defensive positions up and down the hillsides to within 200 yards of the monastery’s foundation. They could see everything they needed to see and direct artillery fire wherever needed without ever having to enter the abbey.

The 80-year-old abbot, Don Gregorio Diamare, and 12 monks had hidden in the crypt during the attack. When they dug out of the rubble, a German officer confronted the abbot and demanded that he sign a formal statement to the effect that there had been no German troops in the abbey. He did so.

Then, on orders from German Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels, the SS took Diamare to a radio station in the German embassy in Rome where he broadcast to the world what had happened to his beloved monastery, weeping openly as he spoke. Iris Origo, an American woman living in Rome, heard the broadcast, which she described as “terribly moving.” Goebbels ordered a film to be made; in the narration he spoke of the Allies’ “senseless lust of destruction,” while Germany was struggling to defend and save European civilization.

The German propaganda campaign made much of the fact that three months before the bombing they had, with the abbot’s permission, evacuated some 70,000 books and priceless paintings from the abbey for safe storage in Rome.

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, the German commander on the Italian front, expressed outrage that “United States soldiery, devoid of all culture, have … senselessly destroyed one of Italy’s most treasured edifices and have murdered Italian civilian refugees—men, women, and children.” It was unfortunate but true that as many as 250 Italian civilians who had taken refuge in the abbey were killed in the raid.

In an effort to counter the German propaganda, Americans also made newsreels, describing the military necessity of destroying the monastery because German soldiers were occupying it and attacking Allied soldiers. “It was necessary,” the Pathé newsreel announced, because the structure “had been turned into a fortress by the German Army.”

Officials in Washington and in London were concerned about the condemnations expressed in newspaper headlines around the world. Two weeks later, Victor Cavendish-Bentinck of the British Foreign Office wrote a memo suggesting that “we had better keep quiet” about the fact that there was no clear evidence that the Germans had been using the abbey for defensive purposes, even though four days before the bombing, The [London] Timeshad indeed written that “the Germans are using the monastery as a fortress.”

The U.S. State Department, on the other hand, took the public position that there was “indisputable evidence” that the Germans occupied the monastery. President Franklin Roosevelt held a press conference at which he said the abbey had been bombed because “it was being used by the Germans to shell us. It was a German strongpoint. They had artillery and everything up there in the abbey.”

The Allied soldiers trying to take Monte Cassino had been correct in thinking they were under constant observation, although it had not been from the abbey. But there was no way the battle-weary men, freezing in their ice-filled foxholes for months while under enemy fire, could have known that the tallest structure around was not housing German soldiers.

The bitterness toward the abbey grew with each failed attempt to take the hill. By the end of January, assaults against Monte Cassino had already cost the lives of 11,000 troops. But despite such losses no one in the Allied high command had requested that the monastery be bombed, not until the arrival of fresh troops and their new commander. More troops were needed because by early February the two leading American divisions, the 34th and 36th, had lost some 80 percent of their effective strength.

Major General Lyman Lemnitzer believed that the American units then on the front line were “disheartened, almost mutinous.” They had lost 40,000 men killed and wounded in the Italian campaign by early 1944, with another 50,000 out sick with everything from trench foot and dysentery to combat fatigue. Another 20,000 men had deserted. A psychiatrist visiting the front wrote, “Practically all men in rifle battalions who were not otherwise disabled ultimately became psychiatric casualties.” They had been in combat too long without relief. British frontline units experienced similar levels of desertion and shell shock.

To replace American losses, a multinational outfit was transferred to Mark Clark’s Fifth Army from the British Eighth Army. Called the New Zealand Corps, it included the 2nd New Zealand Division, the 4th Indian Division, and the 78th British Division. They had had extensive combat experience in Italy and North Africa.

Their commander was 56-year-old Lt. Gen. Sir Bernard Freyberg; although born in England, he moved with his parents at age two to New Zealand. A giant of a man, his nickname was inevitably “Tiny.” Freyberg had been a dentist before becoming a soldier. Wounded nine times in World War I, he had been awarded the Victoria Cross, among other decorations, for bravery in combat.

Clark was resentful that his own units, which had sacrificed so much and lost so many men trying to take Monte Cassino, would not be allowed the honor (and the great publicity for Clark personally) of taking the hill. Clark considered Freyberg “a prima donna [who] had to be handled with kid gloves.” Other commanders, including British and New Zealand officers, thought Freyberg was stubborn, obtuse, and difficult to deal with. Maj. Gen. Francis Tuker, commanding the Indian Division, described Freyberg as having “no brains and no imagination.”

Once Freyberg inspected the battle site, he insisted that the abbey would have to be destroyed before his troops could take the hill. “I want it bombed,” he said, claiming it was a military necessity if his attack on Monte Cassino were to succeed. Many others agreed, including two American generals, Ira Eaker of the Army Air Forces and Jacob Devers of the Army. After a low reconnaissance flight over the abbey on February 14, they reported seeing radio antennas as well as what looked like German uniforms hanging on a clothesline in the courtyard. That same day, the Army Air Forces released an intelligence analysis stating, “The monastery must be destroyed and everyone in it, as there is no one in it but Germans.”

Mark Clark opposed the idea at the time and wrote in his memoirs that, had Freyberg’s outfit been American, he [Clark] would have refused permission to bomb. He referred the request to his superior, British General Sir Harold Alexander, pointing out, “Previous efforts to bomb a building or a town to prevent its use by the Germans … always failed…. Bombardment alone never has and never will drive a determined enemy from his position.”

Clark also noted, “It would be shameful to destroy the abbey and its treasure,” adding that “If the Germans are not in the monastery now [and he was still not convinced they were], they certainly will be in the rubble after the bombing ends.”

Freyberg continued to press Clark and Alexander to agree to proceed with the bombing, reminding them that if they refused his request to destroy the abbey, they would be blamed if his attack on Monte Cassino failed.

Pressure on Alexander also came from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill: “What are you doing sitting down there doing nothing?” Finally, Alexander capitulated and gave his permission to proceed with the bombing.

Clark had to obey, but as insurance he demanded written orders from Alexander commanding him to bomb the abbey so that it would not be seen as his decision. Later, he condemned Alexander for making that decision, which Clark argued should have been his as Fifth Army commander. He added, “It is too bad unnecessarily to destroy one of the art treasures of the world.”

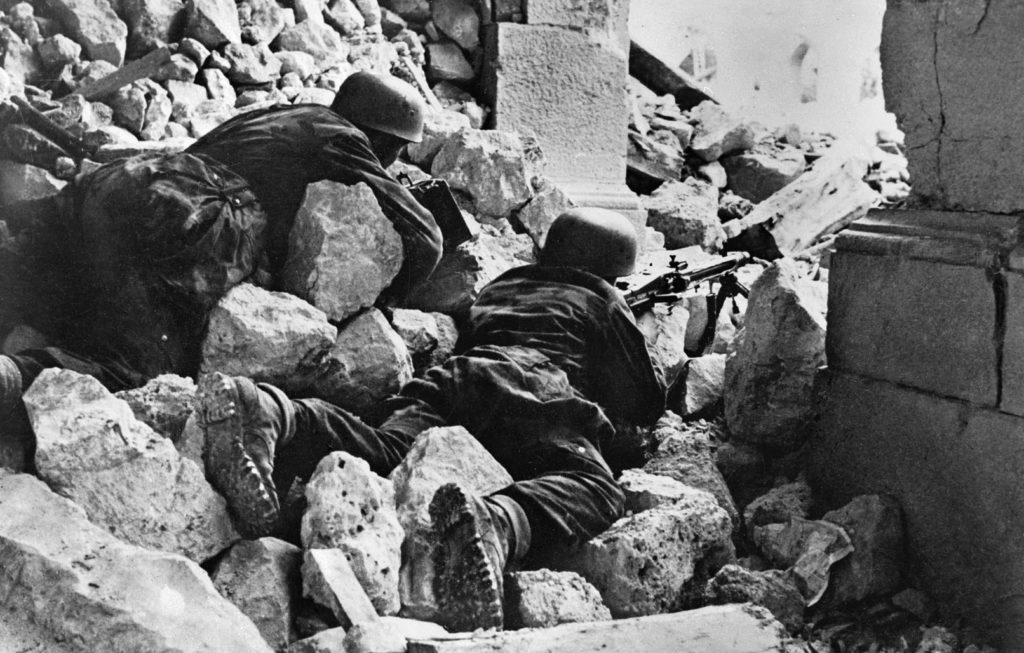

The bombing was considered successful; little was left of the abbey. But the followup ground attack was a costly failure. Clark was correct when he asserted that it had been “a tragic mistake. It only made our job more difficult.” Churchill wrote simply, “The result was not good.” German troops swarmed over the ruins and quickly established defensive positions. Freyberg was late launching his ground attack, which historian Rick Atkinson described as “tactical incompetence in failing to couple the bombardment with a prompt attack.” The attack did not begin until that night and was carried out by only one company, which lost half its men before they had even traversed 50 yards.

Atkinson quoted the official British conclusion that obliterating the abbey “brought no military advantage of any kind.” The official U.S. Army evaluation of the affair concluded that the bombing had “gained nothing beyond destruction, indignation, sorrow and regret.” It had all been for nothing.

It took three more months of fierce fighting before Monte Cassino was finally captured at a staggering cost of 55,000 Allied troops killed and wounded along with 20,000 German casualties. The battle to take the hill was fought by Americans, British, French, Poles, Australians, Canadians, Indians, Nepalese, Sikhs, Maltese, and New Zealanders.

Clark had grown increasingly frustrated, criticizing Freyberg in his diary as indecisive, “not aggressive,” and “ponderous and slow.” By the end of March, the New Zealand Corps was taken off the line, having suffered more than 6,000 casualties in 11 days. Finally, on May 18, a contingent of Polish soldiers reached the ruins of the abbey and ran up a Polish flag to show their final victory.

The reconstruction of the abbey began in 1950, and in 1964 the new structure was re-consecrated by Pope Paul VI. But reminders of the fighting linger in personal memories and massive, well maintained cemeteries. The British cemetery contains more than 4,000 graves, with the British, New Zealand, and Canadian dead in the front and the Indian and Ghurka dead in the rear. The Polish cemetery holds the graves of more than 1,000 men, out of the 4,000 who died there. There are 20,000 graves in the German cemetery with three bodies buried in each grave. An American cemetery, where the dead from Monte Cassino and other battles of the Italian campaign are interred, lies 90 miles north of Monte Cassino and houses some 8,000 graves.

Memories of the Italian campaign and the destruction of the abbey stayed with many of the veterans for a lifetime. Some returned years later to visit the battle sites and graves. In 1994, Cyril Harte, a British soldier, returned to Monte Cassino and described how he felt when “that heartbreak mountain, which had cost the lives of so many infantrymen of all nations, came into view. Just for a moment, my heart stopped beating. That hasn’t changed. It still loomed forbiddingly and I chilled at the thought of the enemy who looked down on us.”

At that moment Harte believed that German soldiers were still in the abbey watching his every move, just as he had been so certain they were 50 years before.

Duane Schultz has written more than two dozen books and articles on military history. His most recent book is Patton’s Last Gamble: The Disastrous Raid on POW Camp Hammelburg in World War II (Stackpole, 2018). He can be reached at www.duaneschultz.com.