By Eric Niderost

King Frederick II of Prussia was busy writing dispatches, his face a study of grim determination as he scribbled out the words by the light of a guttering candle. At the moment he was in Elsnig, a village in Saxony not far from Torgau on the Elbe River, sheltering in a miniscule church that was more like a chapel in size and function. It was the evening of November 3, 1760, and the last stages of a great battle were being fought even as he worked.

Frederick the Great, as he was better known to history, normally would have been on horseback, directing the action and sharing its dangers with his men, who adored him as the semi-legendary Alte Fritz (Old Fritz). The king was only 48, yet his face was that of a wizened mummy, deeply fissured with masses of wrinkles. Earlier that day he had been hit by a spent piece of canister, the force of the blow so severe he was rendered unconscious for a time. When the king came to his senses, the pain and shock were so great, even though he would not admit it, that he was forced to quit the field and seek shelter to recover.

Frederick was sprawled on the church floor, sitting on the steps that led to the altar. A gap between the communion rails that separated the sanctuary from the rest of the church provided a smooth and suitable writing desk. Bunches of straw cushioned the king from the hard wooden steps, and his legs were slightly splayed to keep his balance.

When night fell it looked like the Prussians were headed for a catastrophic defeat, and as he feverishly wrote dispatches, with pauses only to quickly dip his quill pen in a nearby inkwell, the outcome was still unknown. It only added to the anxiety, but Frederick was no stranger to stress in this war, now 41/2years old. It had aged him. The flickering candle produced shadows that could soften, but not conceal, the ravages of time.

In some respects Frederick himself was the author of his own misery. It began in 1740, two decades before, when he had invaded and seized Silesia, then a province of Austria. Prussia had legitimate claims to at least part of Silesia, but those details could be left to pettifogging lawyers. The province was rich, with more than 15,000 square miles of fertile farmlands and a burgeoning cloth industry to boot.

It made geographic sense to Frederick as well. The Oder River ran down from Prussia to Silesia’s capital, Breslau, only 183 miles from Berlin. There was a fairly large population of Protestants, too, who had suffered some discrimination from Austria’s Catholic Hapsburg dynasty.

Frederick’s invasion of Silesia set off a sporadic series of clashes collectively known as the War of the Austrian Succession. The intermittent fighting over eight years ended in 1748 with Frederick apparently triumphant. Prussia kept all of Silesia, and it quickly became an integral part of the kingdom. There was peace for almost a decade as a result of an extended truce. In reality, Frederick’s enemies were only biding their time, using the respite to plan and prepare for a bigger war.

Frederick had sown the wind, and he was about to reap the whirlwind. In some respects, the king had met his match in Maria Theresa, Austria’s ruler. She was not reconciled to the loss of Silesia and was more determined than ever to make the Prussian monarch pay for his aggression. By the mid-1750s a formidable coalition had been created that included Austria, France, Russia, Sweden, and a large part of Germany, then a patchwork of approximately 300 principalities. Of the major powers only Great Britain stood with Prussia.

The Third Silesian War began in 1756, and from the start it was clear that Frederick was not just fighting to retain Silesia, but for the survival of the Prussian state. The Prussian pariah would experience both triumph and tragedy over the next four years. His victories at Leuthen and Rossbach early in the war would establish his reputation as one of the greatest military commanders of his era. Yet he made mistakes, too. As the years wore on and attrition took its toll, there were also terrible defeats. The worst of these defeats was in 1759 at Kunersdorf, where his army was not just defeated but routed.

By his own admission, Frederick could only muster 3,000 men from his original 48,000 after that battle. The disaster at Kunersdorf left the king so depressed his wrote a hysterical letter that hinted at suicide. But the Allies could never seem to agree to a plan that would finish Frederick off. Too much time was spent arguing what to do next, and the movements of Allied armies were poorly coordinated. The Russians, for example, were far from home, and the logistics of supplying their troops was a nightmare.

Both Frederick’s spirits and Prussian fortunes were revived, and the army staged a remarkable recovery. Recruits came in to replenish the depleted ranks, but quantity could not altogether trump quality. There were still some old 1756 professionals in the ranks, but each year they grew fewer in number. “We are very shattered, and our losses and our victories have carried off the flower of our infantry that formerly rendered it so brilliant,” said the king in an unguarded moment.

The king himself was wearing down, beset with illness and exhaustion. He was plagued with fevers and fainting spells. He occasionally even spit blood. The aging accelerated, and he was losing teeth as well. Only the eyes, blue and piercing, displayed Frederick’s still unconquered spirit. By that point, he was forced to remain on the defensive, waiting to see what his still numerous enemies would do before he decided on a course of action.

The Allied plan for the 1760 campaign season backfired. In August they tried to trap Frederick but received instead a severe drubbing in the Battle of Liegnitz. Though not as famous as Rossbach and Leuthen, Liegnitz was a notable victory that buoyed Frederick’s sagging spirits. His soldiers, the king proudly remarked, fought “like his old infantry.”

But the elation was momentary, the respite brief. Lt. Gen. Franz Moritz Count von Lacy’s Austrians linked up with Russian troops and captured Berlin in October. Some parts of the city were sacked, though other parts were spared after paying a hefty ransom. When they heard Frederick was marching to rescue his capital, the Austro-Russian forces quickly withdrew with their loot.

Up to that point, the royal Prussian master had kept ahead of his opponents in the game of bloody chess, but it remained to be seen whether he could successfully checkmate them and gain a decisive victory. It was a time for watchful waiting, and before long it seemed as if an opportunity might soon be in the offing. Field Marshal Leopold Josef Count Daun’s Austrian army moved out of Silesia and west into Saxony. Seeking a strong defensive position, Daun placed himself in and around Torgau, a strategic Saxon town nestled along the banks of the Elbe River.

Lacy’s corps joined him, fresh from their Berlin raid and eager to tell tales of plunder to Daun’s envious soldiers. The Russians were out of the picture, apparently having had their fill of both loot and fighting for the moment. The Russian army withdrew to Frankfurt am Oder, where it would play no part in the future drama.

The Reichsarmee of 30,000 men was also supposed to join Daun. These were troops from the various German principalities that lay under the nominal control of the decrepit Holy Roman Empire. Maria Theresa was co-ruler of the Holy Roman Empire with her husband, Francis of Loraine. Luckily for Frederick, the Reichsarmee apparently got cold feet and marched off in a different direction.

When Frederick heard of Daun’s move he immediately issued orders for his army to march toward Torgau. Apart from wishing to achieve a decisive victory, the Prussian king simply could not afford, both literally and figuratively, to have the Austrians have a foothold in Saxony. Saxon money helped pay for Prussian campaigns, Saxon food fed its army, and Saxon men often became its soldiers. The fact that the Saxon recruits were forced into Prussian service and taxes were wrung from the Saxon population did not matter. Frederick needed the food, money, and men.

The Prussian army advanced to Schilda, about seven miles south of Torgau. Ironically, Frederick had a good idea of what the region was like. His brother Prince Henry had held off a large Austrian army there only a year before, and indeed some of Henry’s fortifications were still in place. Frederick rode on ahead with a small escort to examine the Torgau environs and perhaps refresh his memory on its topography.

Torgau was geographically important because it was the site of a bridge, the most important crossing in the middle stretch of the great Elbe River. The original bridge had been destroyed, but the Austrians had built three bridges of boats that served just as well in wartime conditions. Natural features made the surrounding terrain ideal for defense. The key to the whole region was the Suptitzer Heights, a high ridge that formed a narrow, finger-like plateau running east-west for about three miles.

The heights averaged approximately 200 feet in elevation but were much steeper along their southern edge. The slopes were sandy, making it hard for an attacking soldier’s feet to gain purchase as he ascended; a few scraggy vineyards provided additional troublesome obstructions. The southwestern slopes’ natural defenses were augmented by abatis, a type of field fortification consisting of felled trees with branches deliberately sharpened and pointed outward toward any attacking force. Most of these abatis were Prussian, leftovers from Prince Henry’s stay.

It seemed as if nature itself had been enlisted to promote defense. There was flatter ground between the eastern end of the heights, but much of that space was occupied by a body of water called the Grosser Teich (Great Pond). A large semicircular belt of pine woods cocooned the whole Torgau region, making movements by artillery not impossible, but certainly problematic.

Frederick the Great observed the southern slopes of the heights from afar, but even from a distance he did not like what he saw. He noted how steep the southern face of the plateau was, but also saw that a meandering brook flowed immediately in front of the heights. This was the Rohrgraben, steep-banked and bordered with marshy ground. The Austrians had plenty of artillery that could rain down death and destruction on any attack that came from a southerly direction.

But a plan was starting to form within the king’s nimble mind. He noted that the bulk of Daun’s army was stationed on the small plateau that topped the heights. Having the high ground is always advantageous, but the Austrian army was so large it was rather crowded up there, with little room for maneuver.

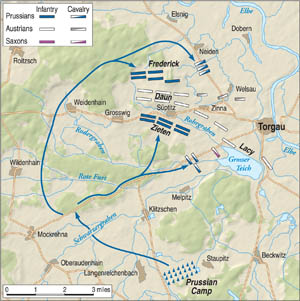

Frederick envisioned a two-pronged attack. The first phase called for General Hans Joachim von Zieten to make a diversionary assault against the southern end of Suptitzer Heights, fixing Daun’s attention in that direction. The second phase involved a wide flanking march by which the bulk of Frederick’s army would secretly circle around the Austrians, their approach concealed by the vast Dommitsch pine forest. If this move escaped detection, the envelopment would place Frederick on the north side of the heights at the rear of the Austrian army. Frederick would be the hammer to Zeiten’s anvil, with the hapless Austrians essentially surrounded with little room to maneuver.

The plan offered endless possibilities. The Austrian army, caught between two fires and unable to escape, would have to choose between surrender and annihilation. Such a defeat would be a major blow to Maria Theresa, one of the most intractable of Prussia’s enemies, and would quite possibly lead to serious peace negotiations.

Frederick, a seasoned campaigner, knew the risks well. The plan was good on paper, but required precise timing. If the Prussians could launch simultaneous, or nearly simultaneous, attacks on the Austrian front and rear, Frederick’s plan had a good chance of succeeding. Much depended on Frederick’s 26,000 men being in position, and they had the longest way to go.

The troops conducting the flank march would have to cover 14 miles and, if all went well, that distance could be covered in about six hours. Zeiten’s command of 18,000 had a much shorter distance to go, about seven miles. Above all it was hoped that the Prussians would not encounter Austrian scouts or pickets along the way. Secrecy was paramount, and much also depended on the element of surprise.

Frederick’s wing of the Prussian army would be composed of three distinct columns. Frederick would personally lead the first column, 15 battalions of infantry accompanied by 1,000 Zieten Hussars. Lt. Gen. Johann Hulsen would lead the second column, which consisted of 12 battalions of infantry. Crude and perhaps a bit unstable, Hulsen’s courage and devotion to duty made him the perfect choice for such an assignment. Lt. Gen. Prince George Ludwig of Holstein-Gottorp would lead the third column, which was made up of 38 squadrons of horse (approximately 6,000 troopers) and two battalions of infantry.

The king’s columns set out at 6:30 am. Long lines of blue-coated infantry stepped off at a brisk pace, scissoring legs moving in a steady cadence. It was cold, and a frigid drizzle alternated with light snow flurries, but the men seemed in good spirits. They wore no greatcoats, so each regiment could be distinguished by the multihued facings of pink, yellow, or red. The cold was so intense that breath misted in small white clouds before mustached faces, and at times the drizzle turned into full-fledged rain.

As the columns marched along, the pine woods grew thicker, slowing progress to a crawl. Tree limbs crowded together in such a way as to form a woody latticework, forcing the soldiers, especially the grenadiers with their tall miter caps, to stoop or risk a collision. The sandy soil was spongy, but its viscous nature was enhanced by the intermittent rains. Soon cannons and their limbers were sunk nearly up their axles in the sandy muck. Ammunition wagons and other vehicles experienced similar difficulties.

Although beset by many of the same difficulties as the others, the king’s columns were still in the lead. Hulsen’s column was much farther behind, and Holstein-Gottorp’s cavalry also experienced setbacks, largely due to human folly and error. It was said the third column got off to a late start because the prince tarried over breakfast. After it did finally move off, it was literally lost in the woods for a time.

Marshal Daun had the foresight to place pickets in the woods. Among the forces assigned to this duty was Grenzer Regiment 66 Slavonische Broder. Grenzer Regiments were irregular, light troops who originally were Croats and other generally Slavic people who guarded Austria’s frontier with the Turkish Empire. They had an unsavory reputation and were prone to looting and ill discipline but were good fighters in open order.

The light infantry sniped at the blue-clad Prussians until the latter unlimbered some artillery and flushed them out of the woods. They fell back, but the damage was done: back on the heights Daun had heard the booming cannon reports and was alerted to at least part of Frederick’s plans. If he had any doubts, they were dispelled later by eyewitness accounts from the retreating light infantry.

About this time an Austrian cavalry unit, the St. Ignon Dragoons, came across the Prussian infantry, but before they could gallop away to report their findings, they found to their horror that they were actually sandwiched in between two columns of Frederick’s foot soldiers. Before they could break through, the Zieten Hussars attacked and made short work of them.

Major General Jean Baptiste Saint-Ignon and most of his regiment were forced to surrender. He must have been the unluckiest officer in Austrian service. Earlier in his career he had suffered seven saber cuts to the head, lost an eye, and had been captured by the Prussians. Exchanged in 1758, he was now a prisoner yet again.

Zieten was taking longer than expected. The old Hussar general was following orders to the letter, and because he had a much shorter distance to travel his pace was slower and more deliberate. He emerged from the southern portions of the Dommitsch Forest, only to run into the advance outposts of Lacy’s corps, which had joined Daun earlier that same morning. Lacy was a tough and resourceful fighter, and he was now in the general area of the Grosser-Tiech lake.

Lacy’s outposts consisted mainly of Grenzer border or frontier troops, in this case Slavic Croats. Dressed in a Hungarian style, their felt hats would be the inspiration for the later development of the shako. As irregulars they could snipe at regular formations with the best, but tended to melt away in the face of a determined attack. A Prussian bayonet charge sent them packing, but when they fell back they reported Zieten’s presence to Daun. The pieces of the puzzle were all in place; now the Austrian field marshal knew exactly what Frederick was attempting.

Daun responded with alacrity, arranging his battalions to deal with this duel threat. When all was complete, the Austrian lines atop the Suptitzer Heights formed a kind of three-sided rectangle. One line of troops faced north, another south, and a third, which formed the connection between the other two, faced west. The Austrian soldiers were so crowded together some regiments merely had to do an about face, literally turn around, to fulfill Daun’s new orders.

Meanwhile, Zieten held back his main force, contenting himself with a kind of desultory artillery duel with Lacy. Some accounts of the battle state that he was supposed to begin his attack when he heard a signal cannon shot from Frederick. But how could he hear such a signal when he was engaged in his own cannonade? Perhaps he was waiting for a messenger, or was due to attack at a prearranged time. We may never know.

While Zieten fired artillery salvoes and Daun waited for the main Prussian attack, Frederick finally emerged from the forest. The king went forward to reconnoiter with a small escort of some aides and Zeiten Hussars. Sweeping the horizon with his telescope, Frederick did not like what he saw. The original plan was for Frederick’s columns to attack Daun’s right flank, that is, the portion near Torgau and the Elbe River. If the Prussians could cut the Austrian army off from the bridges over the Elbe, the whitecoats would have no option but destruction or capitulation.

But now that he was on the scene, Frederick knew he would have to alter his plans. There were strong Austria batteries on the right and if Frederick attacked where intended he’d also be between Daun’s and Lacy’s troops. The only other viable alternative was to shift his proposed attack west, up the heights near Daun’s left. That would mean some necessary delays while the Prussian troops sorted themselves out so they could advance in the new direction.

But then the winds blowing from the south brought an auditory message that the king misinterpreted. Zieten’s cannonade could be distinctly heard, but Frederick thought that it was the sound of the old hussar’s main attack. This brought a new sense of urgency to the proceedings. Frederick could also see a steady stream of Austrian baggage wagons crossing over the Torgau bridges to the relative safety of the Elbe’s eastern bank. This could well be the opening moves of a general retreat by the whole Austrian army

Frederick did not want Daun to escape, and without the king’s attack Zieten might be overwhelmed by superior forces. After all, Daun had some 53,000 men in his command. But Frederick’s second and third columns under Hulsen and Holstein had not yet arrived. Two other factors goaded the king to launch a premature assault: specifically, the weather and the time. The skies were lowering, dark with turbulent clouds that could unleash a full-fledged storm at any moment. Even now, occasional flurries of snow and icy rain pelted the Prussians. It was almost 2 pm and even the most optimistic assessment gave Frederick only about four more hours of daylight.

There seemed no other alternative but to attack, so Frederick used what troops he had in hand, the 10 leading battalions of grenadiers. These elite formations would have no cavalry support and almost no artillery support. Virtually all the heavier cannons were miles away, bogged down in the soggy, viscous, and sandy soil.

There was one unforeseen byproduct of Daun’s concentrations on Suptitzer Heights: his cannons were practically wheel to wheel. The Austrian massed artillery was able to produce a firestorm of death and destruction. The Prussian grenadiers were 800 feet from the Austrian artillery.

The Austrian guns opened up, belching great gouts of smoke and flame from each well-tended piece. Some accounts state the Austrians had 200 guns, but others indicate they may have had upward of 400. The grenadiers were elite troops, but they were still flesh and blood, and nothing living could stand up to this hurricane of lethal metal. Cannonballs plowed through the packed ranks, and when the surviving grenadiers got closer the Austrians switched to canister.

The carnage produced by the guns was “a picture of hell,” wrote one survivor. Cannonballs and pieces of canister peppered the nearby woods, sending a cascade of branches and larger tree limbs cascading to the forest floor. The sound of each individual cannon blast merged with the others, producing one deafening roar that was terrifying even to the most seasoned veteran. “What a frightful cannonade!” Frederick marveled to his aides. “Have you ever heard anything like it?”

Within a few minutes two-thirds of the grenadiers were killed or wounded, and the survivors fell back into the relative safety of the woods. More Prussian infantry came up, and the leading elements of Hulsen’s second column made a belated but still timely appearance. Marshal Daun counterattacked, and though his thrust was easily parried and ultimately repulsed, it was plain that Frederick had to continue his own attacks. If he tried to break off the action and retreat, the Austrian army might surge forward, turn the tables, and ultimately rout the Prussians.

There was nothing left to do but order a second attack, even if it meant putting more men into the meat grinder. “My God!” exclaimed Daun. “Why is the king throwing so many men away?” Many of these Prussian troops were relatively new soldiers and certainly did not have the intense training that was once a matter of course in the 1756 army. Yet they proved themselves again and again as worthy successors of the old formations that had been the marvel of Europe.

The second attack was spearheaded by such regiments as Manteuffel Infantry Regiment 17, Pomeranians who were veterans of several fights. The Prussians pressed forward, stepping over the bodies of those killed and wounded in the first assault. These fresh men also had to endure a heavy cannonade, a storm of metal that tore and eviscerated with horrifying ease. Yet sheer courage gave the Pomeranians the momentum to scale the heights and capture the guns that tormented them.

Gunners were shot and bayoneted, and others were taken captive or put to flight. The decimated Prussians lost no time in spiking the cannons, but Austrian infantry came up to dislodge them from their foothold in the heights. For a time the bluecoats stood their ground, trading volley after volley with their Austrian counterparts, but then sheer enemy numbers forced them to withdraw. The second attack was a failure, but though the Prussians were bloodied they were unbowed.

It was around this time that Frederick was hit by a spent piece of canister and rendered unconscious. He was on horseback at the time, and aides only noticed something was amiss when he let loose of the reins and started to fall backward. One adjutant, a man named Berenhorst, managed to grab the king before he fell off his mount, and together with other aides managed to get their royal master away from immediate danger.

The aides opened up his coat, fur vest, and shirt but found the metal piece had not penetrated the skin. When Frederick came to his senses, he treated the matter with his customary coolness. Indeed, his first words were in French, a language he preferred to his native German. “It’s nothing!” he said. The king had a contusion in the center of his breast, and thereafter nursed a large and painful bruise.

Shortly after 4 pm Marshall Daun took a bullet in the leg. Mastering his pain, he remained in command for another hour or more until he was sure the Austrians were victorious. Then, and only then, he retired to Torgau to have his wound treated. When his boot was removed, it was found to be filled with blood.

It looked indeed like Frederick’s gamble had failed disastrously, and the Prussians were headed for defeat. Marshal Daun even sent a message to Vienna, which turned out to be premature, announcing his victory. But then, when all seemed lost, Zieten finally made some significant moves. He was helped by the fact that an unguarded route was discovered that led to a causeway between two sheep watering ponds and right up to the heights on Daun’s left flank.

Zieten threw everything available through that gap, and before long his troops had a firm foothold on Suptitzer Heights. At the same time the village of Suptitz, which gave the heights its name, was taken by Prussian infantry. Suptitz village had been a hard nut to crack, having been well barricaded and defended by Austrian infantry regiments Harsch 50 and Aremberg 21 supported by three or four medium guns.

The heavy fighting had set parts of the village on fire, and in the gathering darkness the leaping flames created a lurid, hell-like beacon to friend and foe alike. Finally, Prussian units such as Infantry Regiment 31 drove the defenders out and started to scale the heights just behind the burning hamlet. On Frederick’s side of the heights, Hulsen could see what was happening and how Zieten’s new effort could well bring victory if it was properly supported. He was not the kind of man to let an opportunity like this slip by him.

Hulsen resembled Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blucher of the Napoleonic Wars. He was tough, hard bitten, profane, and not overly intelligent. It was said he was an ensign for over a decade. But Hulsen was a good battlefield leader, and it was this quality that caused him to finally rise in the ranks. Age and wounds prevented him from riding on horseback, but he insisted on personally participating in the attack. He placed himself on a gun carriage, summoned soldiers, and commanded them to pull him.

Hulsen took the Schenkendorff (No. 9) and Donha (No. 16) Regiments as the foundation for a new push to claim the heights once and for all. With those two regiments forming the nucleus, he added 1,000 men that were disorganized remnants of previous attacks. They had been rallied by a Major Hans Sigismund von Lestwitz of the Alt-Braunschweg Regiment and were ready for immediate use.

With Hulsen and Zieten acting more or less in concert, attacking from both north and south, the whole strategic picture changed. In some instances Austrian units were surprised and even initially hit from the rear. Desperate Austrian counterattacks achieved nothing, and the whole position of the Imperial army collapsed like a house of cards. With Daun badly wounded, Lt. Gen. Carl O’Donnell assumed command. There was nothing much he could do but order a withdrawal over the Elbe bridges.

Marshal Daun was dumbfounded when he heard the news but was forced to acquiesce. It was past 6:30 pm, darkness had fallen, and the Prussians were in firm control of the heights. The Austrian army retreated across the Elbe. Frederick the Great had won another victory.

The Prussian victory came at a high cost. Frederick lost 16,670 dead and wounded, while the defeated Austrians sustained a butcher’s bill of 8,500 casualties. In addition, the Prussians took 7,000 Austrian prisoners and 49 guns.

The battle’s aftermath was such that many soldiers did not even know if they were among the victors or the vanquished. Thousands of Prussians and Austrians stumbled about in the pitch-black darkness, looking for their units or merely trying to escape captivity. Exhausted by the day’s events, Prussian and Austrian soldiers sometimes bedded down near each other, trusting that they would find out which side won and which side lost and, subsequently, who was prisoner, when the sun rose the next morning.

Austrian Maj. Gen. Vinzenz Felix Graf von Migazzi, disoriented like everyone else, gave orders to an astonished Prussian battalion. He was quickly taken into custody. In at least one instance an entire regiment was captured almost intact, though not without a fight. The Austrian Erzherzog Carl Regiment was Hungarian in origin, a veteran unit with a very high and well-deserved reputation. Surrounded by the Prussians, the regiment refused to surrender and fought on well into the night. A few broke out, but the rest were finally forced to lay down their arms.

Frederick certainly knew how close he had come to disaster, and when the casualty figures started coming in, the numbers left him gloomy and in a very bad mood. The next morning six Prussian dragoons waited outside Elsnig Church, each bearing a captured Austrian standard. Frederick emerged from the church, mounted his horse, and rode away without giving the captured trophies a second glance. The victory had been too dearly bought for the king to feel like celebrating.

Torgau was a bloody battle and, on the surface, seems like a Pyrrhic victory. But appearances can be deceiving, and politically Torgau was a significant win for Prussia and its harried king. In Austria, Chancellor Count Wenzel Anton Von Kaunitz, the principal architect of the anti-Prussian coalition, started to lose heart. After four years of increasingly bloody war, Frederick remained at large and Silesia unredeemed. Kaunitz began to push for a negotiated peace. France, Austria’s ally, was also discouraged by the news of yet another Prussian victory.

Although far from a decisive victory, Torgau fostered a general malaise among Frederick’s enemies. The battle created fissures in the coalition; all that was needed was one more catastrophic event to bring the whole edifice that Kaunitz so carefully crafted tumbling down. That event was the death of the Czarina Elizabeth of Russia, Frederick’s inveterate and implacable enemy. Thus, Torgau was not so barren of results after all.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments