By Christopher Miskimon

Dusk came early as they boarded the convoy of trucks, their olive-drab forms softened by baggy trousers and heavy field jackets.

The 2nd Regiment, 1st Special Service Force (1st SSF) was leaving its barracks at Santa Maria, Italy, for the village of Presenzano, 37 miles north of Naples and currently the headquarters of the 36th Infantry Division.

The trucks slowly made their way down muddy roads using only the dim lights of their blackout drives; no one wanted enemy observers to spot the movement of these new troops to the front. It was December 1, 1943, and as the convoy proceeded a cold rain began to fall, drenching the canvas tarpaulins of the trucks and reducing visibility even further. All that could be seen in the distance were the stuttering flashes of artillery fire.

The trucks arrived in Presenzano at 9 pm. Guides from the 142nd Infantry Regiment met them and led them into the forested terrain beyond the village. Ahead of them lay the imposing bulk of Monte La Difensa, a well-fortified point key to the German defense of the Winter Line, a series of defensive positions designed to stop the Allied advance toward Rome.

It was dark, wet, and cold, but the regiment had to reach its staging area before dawn so the enemy would not know they were there. It was a 10-mile march, and some of the men carried close to their own weight in weapons and equipment. They were fit and tough and up to the task, however. They passed the bodies of Americans killed earlier in the battle and kept going.

Sergeant Donald MacKinnon of the 2nd Regiment’s 1st Company remembered, “There was a menacing feeling about the whole thing.… We were so exhausted with the effort to keep up, clawing [and] sliding our way in the very difficult conditions, that we thought, if we had to go into action when we arrived, we would be useless.”

Finally, the head of the column arrived at the staging area, although the tail end would not arrive until nearly sunup. The men took cover in the trees and undergrowth, hiding themselves as best they could. The rain finally stopped. Behind them the rest of the force waited farther to the rear; the 2nd Regiment was the spearhead.

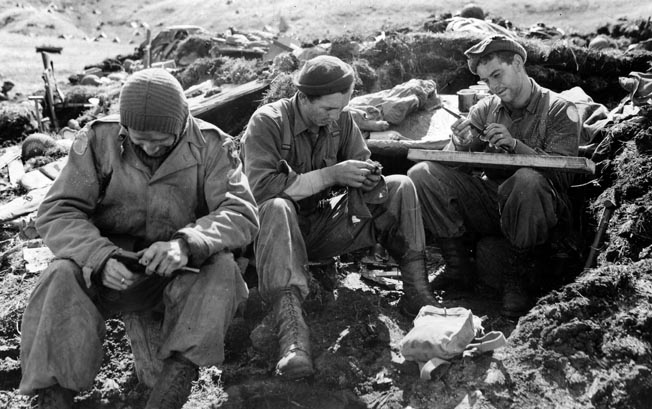

It would be the unit’s first time in combat, and it had been given a particularly hard task. The now hidden soldiers rested and waited through the day; to pass the time they cleaned their weapons, ate cold rations, and awaited the coming of nightfall so they could prove the trust placed in them was well deserved.

The 1st Special Service Force had its origins in early 1942. The Allies, searching for ways to strike at a Germany that dominated the European continent, were looking closely at commando forces. The British had experience in creating and employing such troops, and the newly arrived Americans were eager to incorporate similar units of their own.

The British conceived of creating a commando-style force trained for winter warfare that would spearhead a planned invasion of Norway. They named the concept Operation Plough. Toward that end they researched a tracked vehicle capable of operating in snow that had been conceived by a civilian inventor, Geoffrey Pyke.

When they realized they lacked the ability to develop the vehicle, the British offered Pyke’s concept to the Americans. U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall accepted it and sent the plan to American auto manufacturers for further development. Eventually this would result in the tracked T-15 (later the M-29) “Weasel” cargo carrier.

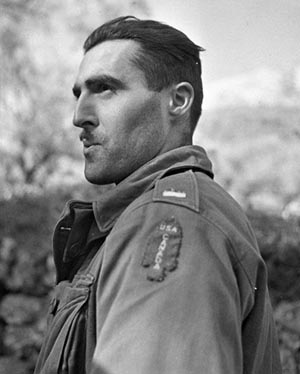

Meanwhile, Operation Plough was studied by Lt. Col. Robert T. Frederick, a West Pointer (class of 1928), then a staff officer at the War Department. It called for a multinational commando force made up of Americans, Canadians, and Norwegians, but Frederick was critical of Plough because it lacked a realistic withdrawal strategy for the troops.

Development continued nonetheless, with the initial idea to form the commando unit using American, Canadian, and Norwegian soldiers in equal numbers. The Norwegians proved unable to provide sufficient numbers of qualified troops, however, so the project went forward using Americans and Canadians.

Having already caught the eye of leaders such as General Dwight D. Eisenhower and Lord Louis Mountbatten, Frederick was given command of the new force, called the Plough Force. He put out a request for volunteers—men who were single, between 21 and 35, and who had had at least three years of grammar school. Further, they had to have had experience in the outdoors, so Frederick required recruits to have worked as game wardens, lumberjacks, hunters, prospectors, explorers, or similar jobs.

The Plough Force was soon renamed the 1st Special Service Force and was activated on July 20, 1942, at Fort William Henry Harrison near Helena, Montana—perfect country for such a force to train in.

That same month the Canadian Army detailed 697 officers and men to the force. Technically, they would remain part of the Canadian Army, but the cost of all clothing, equipment, and expenses would be assumed by the United States government. Frederick had the raw clay of his commando force and set about molding it into a unit worthy of its name.

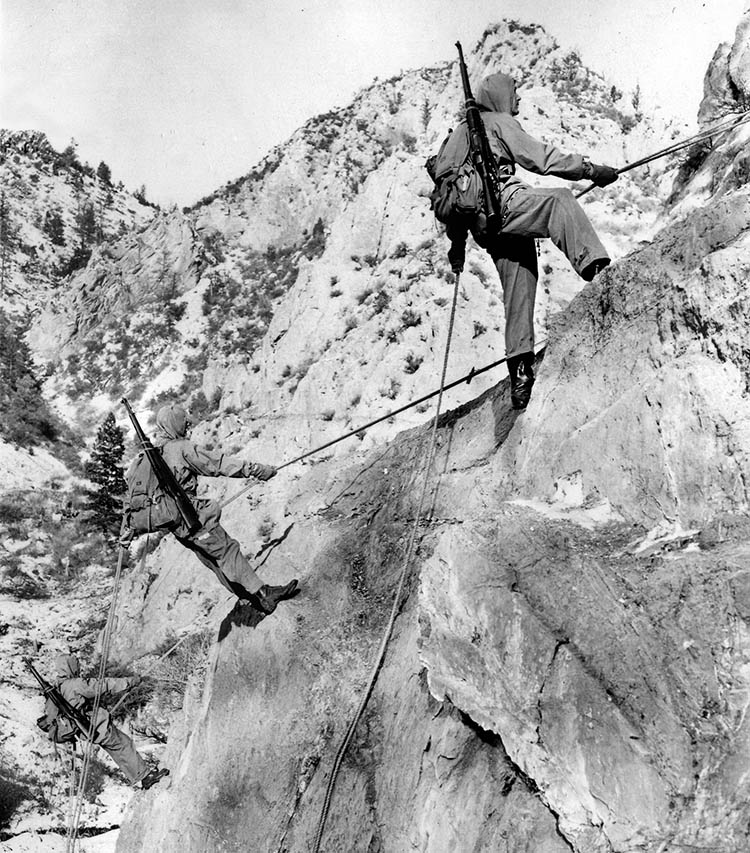

The 1st SSF’s training was among the most arduous given to any Allied soldiers during the war. Physical fitness took a high priority; only men in peak condition would be able to carry out the demanding task of fighting in the cold and snow.

Forced marches could span 36 miles with a full load of combat equipment. The men also received parachute training, though the compressed time available meant they only made two jumps rather than the normal five. This went on for several months; the result was a cohesive unit of tough, resourceful men able to work together under difficult conditions.

First Lieutenant Bill Story recalled, “We did calisthenics, extended calisthenics…. We had the usual pushups and running from place to place, but we also did a lot of walking, a lot of simply walking over the hills and climbing up the mountains. It was excellent conditioning. There was mountaineering, too.”

There was also training in small-unit tactics, weapons to include enemy small arms, and survival. The demolitions training was so intense and frequent that several times the men blew up the wrong targets. Hand-to-hand combat training was provided by Ireland-born Captain Dermot Michael (“Pat”) O’Neill, a martial arts expert and former international police chief in Shanghai. O’Neill showed the men how to kill using knives, garrotes, and just their hands and feet.

The 1st SSF was organized differently from standard infantry formations, closer to that of airborne or other specialized Allied formations, and reflected its binational origin.

The basic unit of the organization was the section, composed of 12 men led by a staff sergeant. The section included demolition specialists, a medic, and a radioman, not unlike modern Special Forces teams. There were two sections in a platoon, which also had a mortar team and was led by a lieutenant and platoon sergeant. Three platoons made up a company.

There were three regiments, but only two battalions per regiment, and a battalion consisted of three, instead of four, companies. The 1st SSF also had a headquarters that included service, maintenance, medical, and communications outfits of various sizes. At full strength there were nearly 2,800 men in the 1st SSF, a robust size for a commando-style establishment.

The service debut of the 1st SSF came in the Aleutian Islands on August 15, 1943, during the invasion of Kiska. The 1st Regiment (Lt. Col. Alfred Marshall) led the assault in rubber boats while the 3rd Regiment (Lt. Col. Edward Walker) came ashore the next day; the 2nd Regiment (Lt. Col. D.D. Williamson) waited offshore as a reserve. The attack proved to be anticlimactic as the Japanese had evacuated three days before, leaving no one to fight.

The event proved no more than a realistic training exercise, though the men were praised for their professionalism by the invasion’s commander for landing in darkness and achieving all their objectives on schedule despite the harsh weather and difficult terrain. Colonel Frederick was also singled out for praise.

To make use of the 1st SSF’s talents, the unit was quickly brought back to the United States and, by September 1943, was training again at Fort Ethan Allen in Vermont. No one told them where their next assignment would be, but they began to receive lessons on Italy and its people, so it was not hard to guess. They soon departed for Hampton Roads, Virginia, where they boarded transports and departed for the Mediterranean on October 28, 1943. Ahead of them lay the Winter Line, a hell of cold weather and close combat.

From September to the winter of 1943, the Allies struggled to move up the mountainous boot of Italy toward Rome and points north. The Allies made progress, but it was tough going. The German commander, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, was determined to make the advancing Anglo-American force pay for every inch of Italian soil it seized.

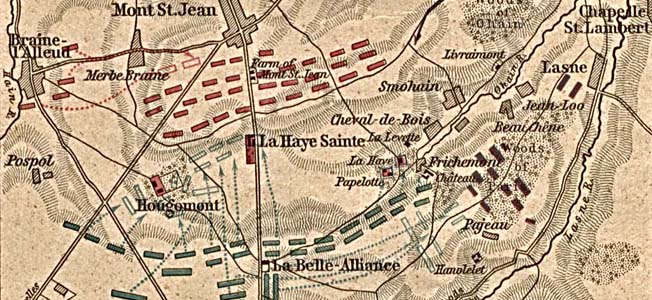

The restricted and rugged terrain gave advantage to the defense. Kesselring chose to form a main line of resistance called the Gustav Line that ran from one coast to the other through Monte Cassino, but he needed time to construct its defenses.

In front of the Gustav Line another defensive work called the Bernhardt Line was quickly formed; along with delaying actions along the Volturno River, this promised to delay the Allied advance until the Germans were ready for them. Together all these fortifications would be known as the Winter Line.

The Bernhardt Line was partly composed of several mountains that overlooked the Mignano Gap—a route that led into the Liri Valley and Rome beyond. Several mountain masses sat on each side of the gap; on one side was Monte Lungo, while the other side was covered by Montes Maggiore, La Remetanea, La Difensa, and Camino.

These mountains made excellent defensive positions and provided observation of the entire area. At 1,900 feet high, Monte La Difensa and its companion peaks formed the key to holding the area; without them the German defense would eventually crumble. Capturing them would be no easy task, however.

A postwar U.S. Army study of the battle stated, “The Winter Line as an entity was thus a formidable barrier to operations of the Allied Armies. There was no single key, no opportunity for a brilliant stroke that could break it. Each mountain had to be taken, each valley cleared, and then there were still more mountains ahead and still another line to be broken by dogged infantry attacks.”

Various Allied units had tried to take these mountains, but a combination of the stiff defense, bad weather, and exhaustion from previous fighting left them unable to do so. Lt. Gen. Mark Clark, commanding the U.S. Fifth Army, needed a force that could break open this mountainous defense and get the stalled Allied drive moving again. The 1st SSF was selected for the task and arrived in the area on November 22.

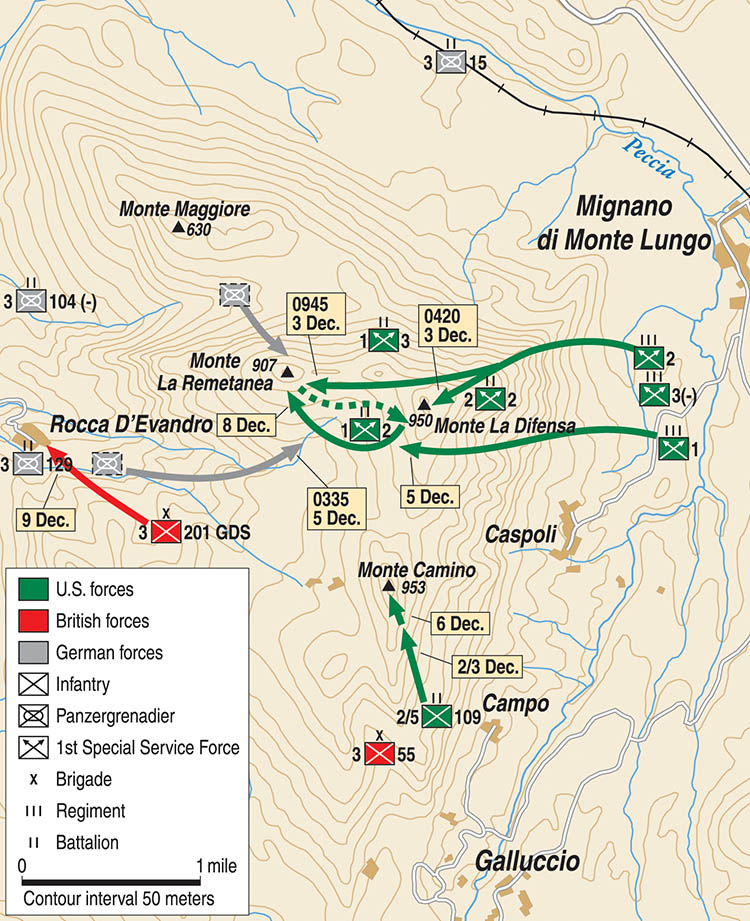

The force was attached to the 36th Infantry Division, which had recently relieved the 3rd Infantry Division along the Winter Line. The men were assigned to take 1,900-foot-high Monte La Difensa and move on to seize the adjoining Monte La Remetanea. Frederick and his men began preparing for the difficult task ahead.

To defend the Winter Line, Kesselring assigned General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin’s XIV Panzer Corps. This formation contained five divisions with different levels of combat experience; as Monte La Difensa was a key point, the veteran 15th Panzergrenadier Division was assigned to hold it.

They were arrayed in depth with good artillery support and numerous mortars that could drop rapid and accurate fire all along the front. The German observers quickly registered their guns and mortars on likely avenues of advance and established supply and casualty evacuation routes. Many positions were formed using local rock to make bulletproof machine-gun nests with interlocking fields of fire.

The objective the 1st SSF was assigned to attack was specifically defended by about 250 men of the 3rd Battalion, 104th Panzergrenadier Regiment. Next to them, about half of the 3rd Battalion, 129th Panzergrenadiers was also in the 1st SSF zone; the other half was spread into the zone of the neighboring British 56th Division. The local reserve for these units was the 115th Reconnaissance Battalion.

One report put the total number of Germans defending the mountain at about 340. They were well supported by artillery, but Allied air strikes and artillery fire made it difficult for them to get supplies forward. By the time of the 1st SSF attack, they had already held off Allied attacks despite being understrength.

Monte La Difensa is a steep mountain overall. Its lower slopes are covered in scrub pine and dotted with boulders, neither of which provided much cover or concealment. The upper slopes held almost no vegetation, and the summit was a shallow depression. One side contained sheer cliffs that could not be climbed without specialized equipment and training.

There were many trails that were too steep even for mules, thus requiring men to be the pack animals. Numerous deep ravines abounded, making any ascent even more difficult. Overall, Monte La Difensa appeared to be a natural fortress, almost impregnable as it towered over the Allied lines.

Colonel Frederick conducted personal reconnaissance of the mountain and sent 1st SSF scouts to reconnoiter it as well. They discovered that the position, although formidable, was not without its weaknesses. Frederick flew a number of aerial reconnaissance missions around the mountain and noticed many of the fighting positions were completely focused on the most likely direction of attack and were not situated or constructed to easily defend against an assault from their flanks or rear.

The Germans themselves later noted this, blaming a shortage of experienced officers and engineers for the shortcoming. Frederick noticed that the sheer cliffs on the mountain’s northeast side were a difficult obstacle, but one that his men were trained and equipped to overcome.

One scouting party was formed by Major Ed Thomas, the executive officer of the 1st Battalion, 2nd Regiment. He took two lead scouts from the 1st Company—Staff Sgt. Howard Van Ausdale and Canadian Sergeant Tom Fenton.

Van Ausdale soon found a way to reach the base of the cliffs. Private Joseph Dauphinais of the 1st Company recalled, “Van was a king among scouts. He was a real mountain man; he could read terrain as you could read a book. He found an excellent route for us to reach the front of the cliff without being detected by the Germans.”

Frederick assigned Lt. Col. D.D. Williamson’s 2nd Regiment to lead the attack; they would have to scale the mountain, surprise the Germans, and then continue through to Monte La Remetanea. The 1st Regiment, under Lt. Col. Alfred Marshall, would wait at the base of the mountain as part of the division reserve.

Lieutenant Colonel Edwin Walker’s 3rd Regiment was assigned separate tasks for its battalions; one would wait at the base of the mountain in support of the 2nd Regiment while the other would act as supply carriers and stretcher bearers. Supporting them would be 14 battalions of divisional and corps artillery, including two battalions of 8-inch guns. Additionally, two battalions of tank destroyers would lend the weight of their guns to the fight.

It was a tremendous massing of firepower, all available in support of Frederick and his men. The mountainous terrain required the artillery to fire at high angles, however, somewhat blunting its effect against bunkers.

The men of the 1st SSF had trained long and hard for their part in the war. They had been disappointed in the Aleutians but now had the chance to prove their unit and themselves worthy of the effort that had gone into creating it. Frederick was determined not to let the opportunity slip through his hands.

As dusk settled over the Winter Line on December 2, it was now time for the 1st SSF to make its attack. A heavy barrage started at 4:30 pm, with some 925 Allied guns saturating German positions all along the front line. Thousands of high-explosive shells slammed into the mountain defenses, joined by the bursting of white phosphorous rounds, which sent burning plumes of white smoke in all directions.

As the artillery crashed and thundered above, the men of the 2nd Regiment slowly made their way up the mountain, trailing each other in single-file columns along the trails discovered earlier by the scouts. Some of them looked up at the barrage and nicknamed Monte La Difensa the “Million Dollar Mountain,” estimating the cost of the ammunition being expended upon it.

In reply, the German artillery opened fire, using its preplanned targeting to hit the various trails they suspected the Allied troops might take, as well as the existing defensive positions of the 36th Division.

As a result, the force’s command post, aid station, and supply points all took fire to varying degrees. This artillery duel, daunting and spectacular as it was, caused little mayhem on either side; the 1st SSF was on the move, and the Germans were well dug in.

Williamson’s 2nd Regiment reached the base of the cliffs on the northeastern side of Monte La Difensa by 10:30 pm; now it was time to begin climbing. Two pairs of men were selected to take the ropes up the cliffs. The lead pair—Staff Sgt. Ausdale and Canadian Sergeant Fenton again—went first, using the best climbing route to the top of the mountain that they had already scouted.

Stealthily the two men picked their way up the 70-degree slope of the cliff using only their hands and feet for purchase. Upon reaching the summit, they had to dodge a nearby German sentry but succeeded in tying off their ropes.

The second pair of men, Private Joseph Dauphinais and Sergeant John Walter, followed behind the two lead scouts and tied their own ropes to the ones already set. The three companies of the regiment’s 1st Battalion (Lt. Col. Thomas MacWilliam) were now set to ascend the cliffs and enter combat for the first time. They carried only their weapons, ammunition, and musette bags, as light a burden as possible to speed their rise.

Behind them, Moore’s 2nd Battalion waited for its turn to climb, carrying with them more weapons and ammunition along with water. Farther down the slope, part of Walker’s 3rd Regiment prepared to carry out its supply runs, loaded down with food, more water, medical supplies, and ever more ammunition. It was a tense time; if any unit were spotted, surprise would be lost and the whole force exposed to German fire.

Finally, at 1 am, Frederick gave the order for the 1st Battalion to begin its ascent. Two at a time, the soldiers made their way up the cliff. The tension grew even worse; each tiny sound of the ascent seemed to echo loudly, causing the men to wonder if the Germans had heard them. A cold rain was falling, making the rocks slick but likely masking what little noise they were making. The artillery had shifted fire, but this was actually good. The rounds striking the new target, Monte Remetanea, caused echoes that further stifled the noise of the Allied climbers.

Two hours later, the 1st Company had scaled the mountain and all stood at the top, formed into a rough skirmish line, creeping carefully to their left. The 2nd Company was entirely at the summit at 4:30 amand took its place in the center.

Finally, the men of 3rd Company made their way up the ropes and occupied the right flank. In their first combat action, the 1st SSF had achieved complete surprise—the Germans were unaware of an enemy battalion in their rear, as they had not guarded it sufficiently due to the cliffs they thought unassailable. Now it was time to attack.

The 1st Company’s 3rd Platoon was at the front of that attack, and scout Howard Van Ausdale was in the lead. Suddenly, as he crept forward, a German sentry appeared and saw Van Ausdale. The American quickly drew his Fairbairn-Sykes fighting knife and stabbed his opponent quietly enough so that it did not alert any others.

Not yet dead, the German rolled down the slope and landed near a sergeant named Waling, who watched the enemy soldier gasping for air. Moments later, Waling continued forward with the rest of the men, now only yards away from their foes.

Suddenly, a German voice called out in the darkness. Stories vary as to what alerted the German; one version points to some loose rocks, kicked as the men covered the last few feet. Another story points to a helmet falling off a man’s head. Whatever the case, just after the German called out he was answered with gunfire.

Sergeant Donald MacKinnon recalled, “That’s when machine-gun fire opened up all around us.” It was about 5:30 am; flares soared into the sky, shedding stark illumination across the rocky landscape. Mortar rounds flew through the air to land among the men, who replied with grenades and fixed bayonets.

The top of Monte La Difensa erupted into a hell of hand-to-hand combat, explosions, and screams of pain and rage. Sergeant Joe Glass of 1st Company later remembered, “We got into it right away.… We had fixed our bayonets because we anticipated hand-to-hand combat, and thank God we did, because we were working real close.… I’m not sure what happened those first few seconds. But in no time at all, I didn’t have a grenade left.”

Glass described how he used one of those grenades: “There was a Kraut down below me over a ledge shooting tracers straight up in the air. I just dropped one right down on his head. They’re good weapons, if you know how to use them.”

The Germans had been taken by surprise, but they were reacting quickly; they had no choice if they wanted to survive. The 2nd Regiment men were attacking just as savagely, though, pouring fire into the enemy positions. Private Kenneth Betts helped man a machine gun, firing on any German he could see. Soon the gun was empty, so Betts picked up a rifle from a dead comrade and went forward. The Germans turned their own machine guns around so they could engage this threat from their rear.

Private Joseph Dauphinais found himself close to an MG-42, its crews firing burst after burst at him. He had little cover and could only watch the muzzle flashes as the bullets sought him out. Finally, one struck him, and he passed out.

The courageous Sergeant Van Ausdale continued to make a difference wherever he went that morning. The last German positions atop the mountain were several machine-gun nests, and the crews of the MG-42s within them were pouring a murderous fire into the Allied ranks.

A sergeant named McGinty was leading his section in an attack on one of the machine-gun nests but had become pinned down. Van Ausdale and his fellow scout Sergeant Fenton laid down fire on the enemy until McGinty could evacuate his wounded. Van Ausdale then rounded up eight men, called for three rounds from the company 60mm mortar, and directed a machine-gun team to lay down its own fire onto the Germans, who were inside a cave.

The incoming fire worked, and Van Ausdale led his section over the ledge and into the cave, using bayonets and grenades to eliminate the defenders. Another MG-42 farther up the mountainside soon fell victim to the same tactics.

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas MacWilliam, the 1st Battalion commander, now sent his 1st Company, under Lieutenant C.W. Rothlin, and Captain Stan Waters’ 2nd Company to take out the remaining nests. They ordered the 3rd Platoon of 1st Company to lay down fire while the rest of the two companies outflanked the machine guns. A platoon under a lieutenant named Kaasch formed a skirmish line while the officer went ahead with two men.

They succeeded in flanking the first gun, causing its entire crew to surrender. The men then advanced on the second gun, but that crew kept firing; a storm of grenades settled the issue, leaving most of the Germans dead around their weapon.

With two more machine guns out of action, most of the remaining panzergrenadiers decided they’d had enough. Many began retreating across the narrow saddle that separates Monte La Difensa from nearby Monte Remetanea. Those who couldn’t get away surrendered; for a few minutes the mountainside was dotted with white flags and Germans with their hands held high.

A few panzergrenadiers were still fighting, however, and this led to tragedy. The 1st Company commander, Lieutenant Rothlin, was dealing with a group of surrendering enemy when he was shot in the face. Accounts vary; some say he raised his head or left a position of cover to check on some Germans who had raised their hands. Others claim he was escorting some men who had already surrendered. Another story stated the Germans would feign surrender with submachine guns concealed behind their backs. Whatever the cause, Rothlin was killed in the chaos of the moment.

In response, several men adopted a “take no prisoners” attitude. The company was now led by 1st Lt. Larry Piette, who spread his men out to make them less vulnerable to incoming mortar and sniper fire. “The Krauts fought like they didn’t have any intention of losing the war,” remembered another lieutenant. “We didn’t take any prisoners. Fighting like that, you don’t look for any.” Another soldier was told to escort a captured officer back down the mountain. He returned just a few minutes later, reporting, “The son of a bitch died of pneumonia.”

By 7 am, Lt. Col. MacWilliam had deployed his 1st Battalion in defensive positions, ready to repel an expected German counterattack. The men were positioned to defend the south and west faces of the mountain; Monte Remetanea lay to the west and was still held by the Germans.

The 2nd Regiment’s 2nd Battalion, under Lt. Col. Bob Moore, had just begun to arrive on the mountaintop. The fresh troops began replacing the 1st Battalion men so they could prepare to push on toward Monte Remetanea; MacWilliam wanted to move on Remetanea before the Germans could regain their balance. The Allied commander also realized the American 36th Division’s 142nd Regiment was attacking adjacent to them and would be hard pressed to hold their gains unless the Germans were pushed back farther.

The 1st Battalion formed up to advance, and true to form MacWilliam and his staff took position at the front, ready to lead their men forward. German mortar and artillery fire began landing among them, and enemy snipers fired at whatever target appeared in their sights. MacWilliam, at the head of the 1st Company, had just given the order to move out. In the very next moment a mortar round exploded in their midst, killing the commander and two others.

One soldier recalled, “I looked back just in time to see them disappear—it was just a red mist.” The rest of the staff was wounded, blast and shrapnel pelting the entire group.

The much-needed assault, necessary to prevent the Germans from regaining their balance, was momentarily stopped in its tracks. Taking MacWilliam’s place was Major Ed Thomas, the executive officer of 1st Battalion, 2nd Regiment.

Colonel Frederick soon arrived as well and told Thomas to wait until more men and ammunition could be brought up. The colonel had made his headquarters at the base of the mountain but climbed the ropes to personally see what was happening.

Frederick moved among the troops, sending out patrols and slowly expanding the patch of rocky ground the 1st SSF held and constantly exposing himself to enemy fire to lead the men forward. One captain recalled, “His indifference to enemy fire was hard to explain, as there were times when a heavy barrage of mortar fire would send us scurrying for cover only to come back and find him smoking a cigarette—in the same position and place we had vacated in a hurry.”

The 1st SSF men grimly held on; a lieutenant remembered sharing his foxhole with an enemy soldier. “He didn’t bum any cigarettes or anything, because he was dead.”

At about 8:35 am, Frederick was given a message from a British liaison officer stating that the adjacent British 169th Brigade had taken several hills including Monte Camino. Unfortunately, the Germans actually still had a presence on the northwestern side of Camino and were using it to direct fire on the 1st SSF. They were also reinforcing the saddle between Difensa and Camino. The U.S. 142nd Infantry Regiment was also pushing forward to its objectives, unwilling to wait for Monte Remetanea to be taken.

The resupply efforts were taking time, so Frederick decided to wait until dawn the next morning for 2nd Regiment’s attack. He told the unit’s leaders to use artillery fire overnight against the German positions and to send out patrols to eliminate any Germans to their south. Later, as Walker’s 3rd Regiment began arriving with fresh supplies, word came that the British had lost Camino to a German counterattack.

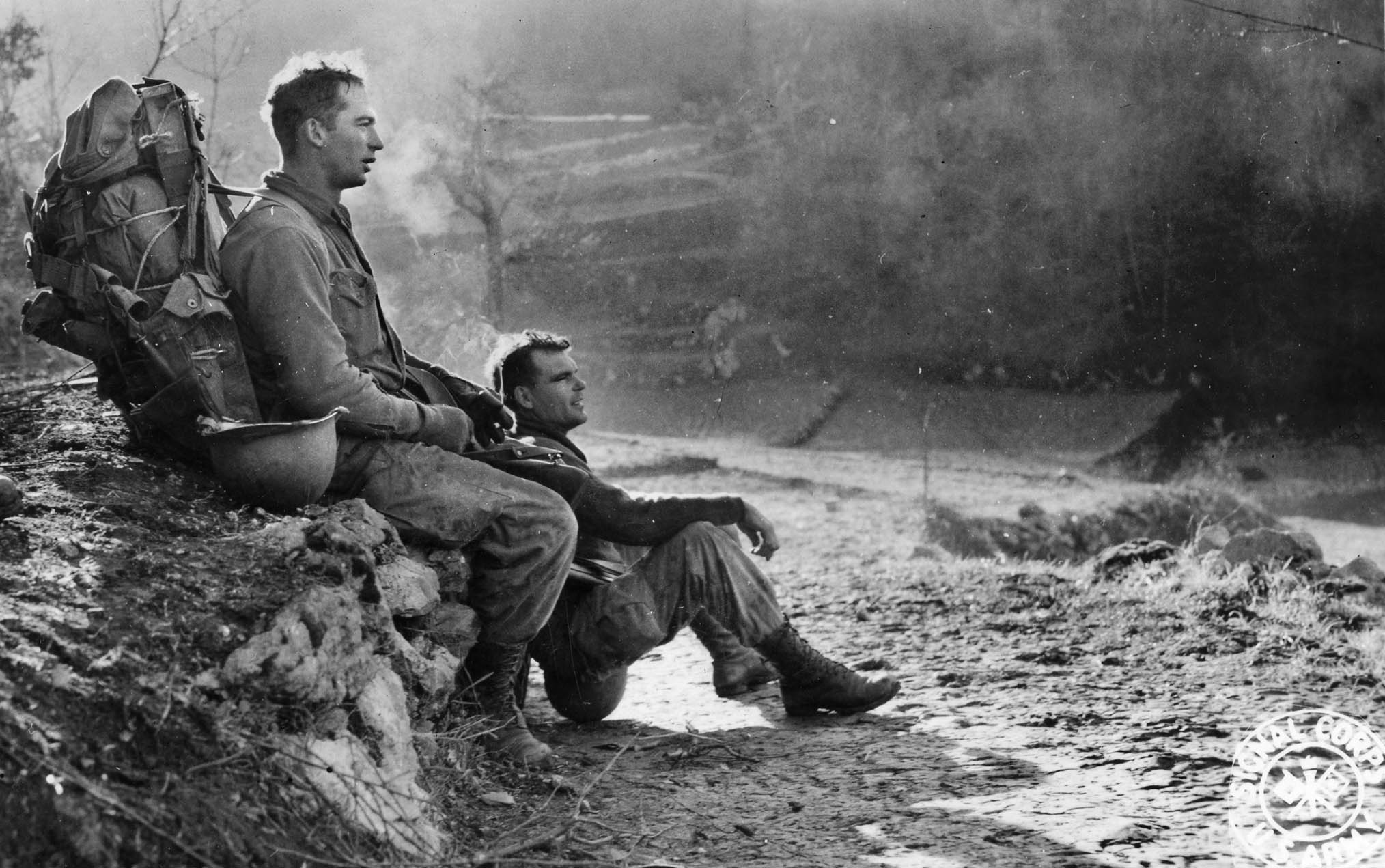

That resupply effort was almost as miraculous as the successful ascent of the mountain by the attacking 1st SSF men. Each man carried a packboard on his back, loaded with jerrycans of water, packages of rations, and heavy burdens of ammunition. Blankets and medical supplies added more weight. It took eight hours to get up the mountain with such a load, and snipers shot at them the entire way.

Once at the summit, their supplies unloaded, they now had to return to the bottom, usually carrying a wounded man using a complex arrangement of ropes to lower him to the bottom. It took 10 hours and eight men to get one casualty down Monte La Difensa and to a waiting ambulance.

At first, some of the men grumbled that acting as supply troops was beneath their training and skills. Such talk stopped once they realized that no ordinary medics, stretcher bearers, or quartermaster men could possibly have gotten either up or down the mountain. They were saving lives no one else could have saved.

Colonel Frederick requested additional supplies, causing raised eyebrows among the supporting logistics officers. He wanted whiskey and condoms sent to the top of Monte La Difensa, reportedly causing some to wonder what kind of party was happening far above them. Frederick’s intentions were much less sordid, however; the whiskey was to warm the men, who were suffering in the cold and damp weather. The condoms were to be placed over the muzzles of their weapons to keep them dry, a trick the 1st SSF picked up in the frozen Aleutians. The unusual request got as far as Mark Clark, who approved it, saying something like, “They took the mountain, give them what they want.”

The Germans continued to do all they could to prevent the Allied troops from reaching the top or getting back down again. Snipers used tracer rounds to direct mortar and artillery fire. They knew where the trails were and swept fire back and forth along them, concentrating on each end of the paths to prevent easy escape. Many 1st SSF men were wounded and the rest exhausted in this deadly and dangerous work.

As the resupply effort went on, Frederick’s intelligence officer, Lieutenant Finn Roll, interrogated 43 Germans taken prisoner atop La Difensa. He learned their enemy was the 15th Panzergrenadier Division, at least a battalion of which was still dug in at the top. Roll also knew about 75 enemy dead had been counted from the morning’s assault; the 1st SSF had lost about 20 killed and 160 wounded in the same period.

Several men remembered one German medic who had declined to be evacuated with his fellow prisoners. Instead, he stayed at the summit, tending to the injured there. One soldier suffered from a sucking chest wound, a serious and often fatal condition that the Allied medics had been unable to remedy. The experienced German medic treated the man successfully; the wounded he treated hoped to thank him later, but his eventual fate is unknown.

After nightfall, rain added to the 1st SSF’s plight. The tired men atop La Difensa peered into the dark and fog, tensely awaiting a German counterattack. Patrols groped around, trying to determine the enemy positions and strengths.

While the 2nd Regiment endured, down below the 1st Regiment was released from the divisional reserve, and its commander, Lt. Col. Marshall, moved them to reinforce their fellow troops on La Difensa. Not long after they started along the route they were spotted by alert German observers, who fell back on their proven tactic of marking the Allied position with tracer rounds. The luminescent bullets were soon followed by a heavy barrage of cannon fire that last 20 minutes. In that brief time, the regiment’s strength was reduced by 40 percent—a horrible number of casualties. The remainder quickly regrouped, however, and moved up the trail to join their comrades.

At dawn on December 4, the situation was still far from clear. There were reports of strong German positions south of Remetanea, and Frederick still worried about a counterattack. He decided to postpone his attack another day, until dawn on the 5th. Throughout the day more patrols went out; often the 1st SSF men coming down the slope from La Difensa met German patrols coming up from Remetanea.

It was foggy, and the rain continued; sometimes the mist would clear suddenly, exposing men to snipers. Men shot at each other through the fog; if it cleared, all would take cover and wait for the patrol leader to decide whether to attack or disengage. Accurate mortar fire made the situation even worse. A German specialty was a six-round volley with an adjustment afterward. Major Ed Thomas, who had taken command of the 1st Battalion after MacWilliam was killed, became a casualty when he jumped into a foxhole during a bombardment and landed on a soldier’s bayonet; Major Walter Gray assumed command.

In the afternoon a pair of prisoners was brought in by a patrol. In return for a few boxes of K-rations, these POWs revealed an impending counterattack planned for 3 the next morning. A nearby artillery observer confirmed the information when he saw about 400 Germans gathering nearby. Artillery was called in to break up the concentration, and the men on the front lines were told to stay alert throughout the night.

A small comfort was gained when the prisoners also revealed the Germans were in a poor state of supply as well. The rain was flooding their routes, and many of their mules had been lost to Allied artillery fire. Eventually the rain ceased but it was another cold night on the mountain, bolstered only by the few sips of whiskey each man received, compliments of Colonel Frederick. The expected enemy attack never came.

The next morning, the 1st SSF’s attack was again delayed, but a trio of patrols went out to gain more information in the hopes the attack could proceed that afternoon. One patrol sought to find the enemy on Monte Remetanea but found no activity. The second pushed out toward the 142nd Infantry, but no contact was made with them or the enemy. The last patrol likewise went to find the British 169th Brigade but could not make contact either. Despite not being able to find the flanking units, Frederick was encouraged that the enemy had not been contacted either, and so he prepared to attack.

At 1 pm,Major Gray moved out with all three companies of 1st Battalion, 2nd Regiment, bolstered by one company from 3rd Regiment. They moved on Remetanea, the bulk of the troops along the northern slope of the ridge with patrols using the southern slope. The patrols soon came under mortar and machine-gun fire, which soon spread to the entire attacking force, causing it to stop halfway to the objective and dig in. More patrols went out while most of the troops waited until dark.

Moore’s 2nd Battalion, 2nd Regiment, reinforced by a company from 1st Regiment, moved toward the saddle between Monte Camino and La Difensa at about 4:30 pm, hoping to crack the German defenses there. Under cover of smoke, the 5th Company, under a Captain Hubbard, led the assault.

When they approached the first of the German positions at a pair of knobs they called “warts,” the Germans opened fire. The 1st SSF men lacked cover and had no choice but to push on or be destroyed by mortar fire. They reached the enemy bunkers and dropped grenades into the firing embrasures. Lieutenant Wayne Boyce, leading the 1st Platoon of 5th Company, led his men to flank the enemy on three sides, drawing their full attention in a battle for survival. The first wart was soon in Allied hands.

Boyce regrouped his platoon and led them on an attack on the second wart. He was hit during this attack but stayed in the fight, refusing to stop or be evacuated. The lieutenant leapt into a German machine-gun nest, using his knife to kill several Germans until he was caught by a burst from a submachine gun. Still, he stayed in command of his men despite serious wounds. Before long the second wart was in their hands, but tragically Boyce died just as his men completed the task.

The 2nd Battalion, 2nd Regiment occupied the warts and dug in for the night. More reinforcements came up, but the night passed without a German counterattack. Some of the men were able to watch the British artillery pounding a German-occupied monastery on nearby Hill 963.

The next morning at 10, the 1st Battalion, led by Major Gray, attacked Monte Remetanea. They took the now ubiquitous machine-gun and mortar fire from nearby hills, but there was little direct opposition. The Germans were retreating and had left only a token force as a rear guard. The 1st SSF’s attack came so quickly that it took many Germans by surprise, in particular a bivouac area where the enemy still had tents pitched.

A number of Germans were killed when they came running out of their tents, firing wildly. Many more were captured; one 1st SSF captain personally took 19 prisoners. By noon Monte Remetanea was at last in Allied hands.

With that objective secured, the unit pushed down toward the valley below, realizing that the enemy was in retreat. Frederick wanted to capitalize on the situation but knew his men were suffering from exhaustion and the cold weather. Snipers were still a problem, and the men noticed every time they were using their radios German mortar fire soon fell on the radio’s location.

Frederick saw a group of Germans coming up a draw southwest on Monte Camino, and he told the 36th Division commander that, unless the British could take Camino by nightfall, he should let the 1st SSF attack it instead. No such order came, and the men dug in for another night, enduring more sniper and mortar fire and awaiting a counterattack that thankfully never came.

Finally, on the morning of December 7, the Force men linked up with British patrols on their flank. A near-tragedy occurred when a British patrol fired on some 1st SSF men in a dense fog. The situation was cleared up before anyone was hit. Another British patrol arrived at the 2nd Regiment headquarters and was surprised by how many majors and colonels were present at the front lines. Lt. Col. Williamson told them that the unit believed leaders should lead from the front—so that’s where they were.

The battle was winding down, but there was still fighting to be done. A platoon-sized patrol from 1st Battalion, 2nd Regiment was sent to link up with the British. It instead came across a strong enemy position defended by 50 Germans. The patrol leader realized he was ill equipped to take on such a large force of well-armed enemy and wisely pulled back.

Elsewhere, 1st SSF men hunted for the few remaining snipers who still plagued them; most of the snipers were lone soldiers cut off from their comrades. Other Force men struggled to bring the last of the wounded down the mountain.

Overhead, the weather cleared and Army Air Forces transports tried to drop additional supplies, but most fell out of reach. The next day, December 8, Major Gray sent his entire battalion to take out the German outpost his patrol had found the day before. Plenty of artillery was laid on, and the clear weather aided in coordinating the attack.

The 1st SSF men advanced under the cover of a rolling barrage. Fully half the German force was killed, and seven were captured. It was the last fighting the 1st SSF would do on the mountain. The German troops were found to be part of the Hermann Göring Division, sent in to bolster the rear guard.

That night two battalions of the 142nd Infantry arrived to take over the Monte La Difensa area. The 1st SSF was relieved and slowly made its way back down the mountain. Later, in daylight, some were amazed to look at the terrain they had climbed and attacked through.

Their replacements were similarly amazed at the state of the men; many stared at the bloody, filthy, exhausted men who had accomplished in a few days what the regular infantrymen had been unable to in weeks. The next day, they boarded trucks for a journey back to where they had started, the barracks at Santa Maria.

On December 10, Colonel Frederick received a pair of messages. The first was from the II Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes. It acknowledged the difficult conditions under which the unit fought and congratulated them on a mission well accomplished. The second message was from Lt. Gen. Mark Clark, commanding the Fifth Army. It further noted the difficulty of making a successful night attack in mountainous terrain against a tenacious enemy. Clark also praised the 1st SSF for doing so well in its first combat action.

In six days of combat, the unit had suffered about 25 percent casualties, including 73 dead, nine missing, 313 wounded, and 116 suffering from exhaustion. The casualty lists showed the dreadful causes: gunshots, mortar fragments, grenade lacerations, concussions, and fractures, even amputations. It was withdrawn from the line for 11 days of rest and reconstitution.

Afterward, the 1st SSF went back into the fight, tasked with taking more mountaintops that other units had been unable to seize. On one of them, Monte Majo, Marshall’s 1st Regiment ran so low on ammunition that it had to use captured weapons. Despite this, it repulsed more than 40 counterattacks.

In February 1944, the unit was sent into the Anzio beachhead, the Allied attempt to outflank the Winter Line and expose Rome to capture. There, remnants of the decimated Darby’s Rangers were sent to the 1st SSF as replacements. The unit held a place in the line and took part in leading the eventual breakout in May.

Later that summer, the 1st SSF would be incorporated into the First Airborne Task Force for the invasion of Southern France. Afterward, however, the unit, which had accomplished so many arduous missions at long odds, was simply disbanded. It was a common fate for many such units during the war. Many senior leaders lacked familiarity with relatively small, specialized organizations that did not easily fit into a conventional order of battle.

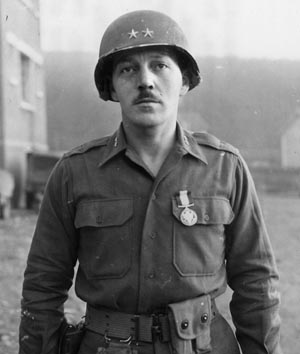

In its relatively short life, the 1st Special Service Force proved what a well-trained, motivated and disciplined group of soldiers could accomplish when they were well led and given tasks within their broad capabilities. Frederick was, in time, promoted to major general and later commanded the 45th Infantry Division. He was one of the youngest generals of the war, retiring in 1952.

The exploits of the 1st SSF would be celebrated in the 1968 war movie The Devil’s Brigade, starring William Holden as Colonel Frederick. A number of books have also been written on the unit, and a website honoring the 1st SSF men (www.firstspecialserviceforce.net) is full of personal photographs of the men and the locations they served in. Both the modern-day Canadian and American Special Forces draw important parts of their heritage from the 1st SSF, which both still honor today.

I met one of the FSSF while at the bank here in Michigan. he said his name was John Stempian. (Unsure of the spelling) He had some great stories that he told. He was surprised when I recognized the patch that he had on his coat. I told him my dad was a paratrooper in the 82nd and he told me about them.

Our Uncle Felix Polito turns 100 in the next few days. He was in 6-2 FSSF aka Devil’s Brigade.

We’ll celebrate his birthday, service, and the return of his Purple Heart as well as receiving his Congressional Gold Medal. You see, as strange as it seems, there were TWO soldiers named F. J. Polito, Both from the same hometown, but not related. Their father’s names were both Joe, and they were Both in the FSSF. Felix in 4-2 and Frank in 6-2.

Due to this, Uncle Felix had been deemed deceased, KIA, or simply considered a duplicate of the other F. J. Polito. So Felix never was invited to any of the FSSF Reunions, nor made the list of survivors.

It’s with Great Joy that this April 24th, 2022 we Celebrate our Hero at the WWII Museum in New Orleans, with an Army General presenting his Purple Heart, and a Board Member of FSSF Foundation, presenting his Congressional Gold Medal.

God Bless All of you at the Warfare History Network for keeping their memories alive.

Thank you,

Bob Holbrook

[email protected]