By Robert Heege

It was late in the morning of November 30, 1853, and the Black Sea was living up to its name. Aboard the 44-gun Ottoman warship Auni Allah, the men of the fore watch, their duty done, had only just headed below decks, tramping wearily down the rickety wooden steps leading into the rabbit warren of dank, dark passageways deep within the bowels of the ship. Happy to be relieved and chilled to the bone, they were eager for the welcoming sight of the row upon row of dingy hammocks slung beam to beam across the length of the berth deck and the promise of sleep that awaited them. But fate, it seemed, had other plans.

The storm that had so relentlessly threatened to batter their ship into matchsticks had finally petered out. Several days before, in the dead of night, with their creaking conifer masts groaning under the strain of this seemingly relentless autumn gale, Patrona (Vice Admiral) Osman Pasha, the 61-one-year-old Turkish officer in overall command of both the ship and the flotilla to which it was attached, had been compelled to suspend squadron operations for the duration, prudently deciding that it would be better for the Auni Allah and her sister ships to put in at the nearest friendly port and wait it out.

From the quarterdeck of the Auni Allah, which was Pasha’s flagship, the order went out accordingly, and the corresponding signal pennants were sent fluttering up the halyard, directing each of his captains trailing along in formation to follow their lead, come about at once, and proceed due south with all possible dispatch.

With their storm-drenched canvas sails whipping in the wind, the rest of the flotilla swiftly corrected course and followed after the flagship. Changing tack, even as the punishing winds and the sea swells lashed them without respite, they made for Cape Sinop, where the Isthmus of Ince Burun curled outward into the sea like a beckoning finger and the moribund northern Anatolian coastal town of the same name offered the Auni Allah and the other 11 vessels of the patrolling squadron the promise of a refuge harbor, a safe haven in Turkish home waters through the long, tempest- tossed night.

But this all too idyllic sanctuary proved to be woefully short lived, for the break of day was not their friend. As the rising sun began cutting its way through the lingering cloud cover, spreading its gleaming rays over the frosty, white-capped waves, the dark specter of an altogether different kind of storm was already gathering on the near horizon. Indeed, as Osman Pasha’s ships lay complacently at anchor they did not yet know that they were literally squatting in the eye of this new maelstrom. As the morning mist slowly began burning away toward the early afternoon, the squadrons’ sailors going about their business above and below decks suddenly found themselves being jolted out of their doldrums by the raw shouts of the lookouts. This alarm was quickly followed by the urgent whistle call to action stations.

As Pasha and his captains squinted anxiously through their spyglasses and junior officers aboard every ship gripped the deck rails with throats gone dry, a pounding, Western-style drumbeat echoed across the harbor electrifying each ship’s company. The drums were quickly joined by the dour notes of the buq, the traditional Mohammedan trumpet horn whose shrill alarm was soon resounding loudly throughout the entire squadron.

In seconds, the sultan’s proud wooden ships sprang to life, reverberating with the sound of the purposeful, thumping footfalls of their respective crews as barefooted comrades began pushing through the lower passageways and rushing to their posts fore and aft on the upper decks, each man on every ship eager to answer the pasha’s call to duty.

One of the cardinal axioms of warfare is to learn to expect the unexpected. However, moored at anchor as they were in one of their own home ports, the Ottoman sailors had believed they were safe. The crewmen aboard ships were a hardy lot, but they were psychologically unprepared for what came next, the solitary sound of one of the flagship’s gunners suddenly piercing the overcast gloom with a lone cannon shot plunging impotently into the depths.

There followed an eerie calm that went on for several odd seconds. Even then, some of the old salts in the squadron might have been forgiven if there were still those among them who remained hard pressed to imagine that they were actually in any real danger. In any case, that lone gunner’s report was soon enough answered in spades. Aboard the Auni Allah the hapless swabbies below decks barely had time to blink. The next thing any of them knew, the fusty tranquility of their womb-like world below the waterline suddenly erupted, descending pell mell into a pandemonium of splintered wood and shredded humanity. All around them the briny wooden walls began to buckle and burst, blasted to bits by an unseen enemy and a weapon of destructive

power hitherto unknown upon the high seas. Shot to pieces in a matter of moments, the Auni Allah’s forward bulkheads shook and shuddered, groaning like a dying sea beast as they began collapsing inward. Hoarse shouts and oaths to Allah competed with the screams of the wounded as desperate crewmen clam- bered over the mangled and the dead in a desperate bid to escape. Suddenly, there was a terrific explosion. The ship listed violently, everything went black, and the dark green sea came pouring in.

Taken almost completely unaware, bunched and bottled up in the harbor like so many sardines in a tin, the Turks found it difficult enough even to weigh anchor with any speed, much less maneuver to any advantage. The Auni Allah and her sister ships, the whole of Osman Pasha’s flotilla, quickly realized to their horror that, barring some immediate manifestation of the baraka, they were little more than sitting ducks, entirely at the mercy of what would shortly prove to be a devastating, pitiless naval bom- bardment that was now poised to pulverize each and every one of them.

Preoccupied by the storm that had threatened to shred their mainsails, Pasha and his captains, having been caught asleep at the helm, were all in for a deadly penance. In a way, they were about to pay the butcher’s bill for the negligence of generations. They now found themselves defenseless because, like the empire they served, they had failed to detect the immediate presence, much less sufficiently appreciate the threat posed, by a hostile, resolute enemy of determined, single-minded, shark-like ruthlessness, that had been circling the waters, almost under their very noses.

Like languidly complacent Sultan Abdulmecid I in Constantinople, they had been blind to the ever more menacing intentions of a ruthless, steadily encroaching nemesis whose warships now boldly appeared directly before them in strength, massing at the entrance to the harbor to test their seamanship and bedevil their disbelieving eyes. Here then was the opening shot of what was soon to become the Crimean War.

Turkey and her increasingly sclerotic empire were long derided as the perennial “Sick Man of Europe.” Turkey was once the primary menace to Western civilization, but its many decades of gangrenous decline were truly a dismal reversal of fortune. It had not always been so, and no student of history, military or otherwise, could say that the Turks had not had a good run. But for the once mighty Turks, it was the rise of Russia, a great power coming late to the scene, that more than any other factor would prove to be their undoing.

Starting in the late 17th century, the dynamic young Czar Peter the Great feverishly began the arduous task of modernizing his vast but back- ward domains. Importantly, he built a large modern navy modeled after those of his West- ern European counterparts.

By the 1770s, his successor, Catherine the Great, had robustly waged a short, sharp war against the Ottomans in a quick bid to enlarge the territory of her already huge realm at Turkish expense. She successfully managed to wrest the whole of the Crimean Peninsula from Turkish suzerainty and sent her spanking new ships, captained by some of the world’s most illustrious seamen-for-hire, such as American hero John Paul Jones, into the northern Black Sea directly across the water from the Turkish homeland. The stage was set for all that followed over the course of the next century, and the events at Sinop would prove to be the linchpin.

The rise of Russian power and prestige upon the world stage was increasingly linked to Turkey’s declining fortunes. More than any other rival, the Russians were a constant source of misery for the beleaguered Turks. Doggedly pursuing their quarry, continuing to lust after more and more of her territory, the Russian czars steadily increased their empire throughout the 1800s by continually nipping at the edges of the Ottoman domains.

This created a sort of international chess match as the Western European powers, pri- marily Great Britain and France, grew anxious at the prospect of the Russians gaining a foothold on both shores of the Black Sea. The thought of Russia one day seizing the Straits of the Bosporus and sending their warships sailing straight down through the Dardanelles into the Eastern Mediterranean was almost too chilling for the West to contemplate.

Perversely, the very same European powers that had feared the wrath of the Turkish invaders for centuries felt compelled to bolster the Ottomans’ fragile regime to deny each other and the Russians an advantage that would upset the geopolitical balance of power.

Despite his sincere reformist ambitions, heading into the second half of the 19th century the hopelessly corrupt Ottoman court of the spend-thrift Sultan Abdulmecid I was used to being financially bailed out by a series of massive loans supplied, somewhat begrudgingly, by successive British and French governments, that they came to rely upon these glorified welfare checks as a matter of course.

From his throne in the Winter Palace outside Saint Petersburg, Czar Nicholas I watched the piecemeal defanging of the once fearsome Grand Turk with increasingly undisguised delight. With each passing year, the number of Turkish ships plying the waters of the Black Sea became smaller, even as those of his own celebrated navy increased steadily. His generals were still dining off the reflected glories of his illustrious ancestor, Alexander I, who, along with the infamous Russian snows, had put an end to Napoleon’s glory-hungry megalomania in the winter of 1812.

Sensing a ripe opportunity to profit from the misery of his rival ruler, in 1853 the opportunistic Czar Nicholas made up his mind that the time was right to consolidate and expand his acreage in the disputed peaks and valleys of Transcaucasia.

Hoping to pull off a fait accompli, the czar sent his armies pouring into the sleepy Ottoman back-waters abutting his already rambling realm in July 1853 in an effort to Russify as much of the long neglected territory as possible, even managing to snatch up several poorly defended Turkish fortifications along the river in the process.

The sultan, unexpectedly roused from his torpor by this bold challenge to his sovereign borders, angrily protested. He also lodged an emphatic complaint to his British and French paymasters, who attempted to mediate. When the czar ignored Turkish demands for an immediate Russian pullback, the sultan rashly declared war on the Russian Empire.

Alarmed by the prospect of the Russian hordes steamrolling their way to Constantinople in a fortnight, the British and French issued a peculiar joint statement. They assured the czar that since war had been declared on him, they recognized the right of Russia to defend herself and would pursue a middle course along the lines of a guarded, conditional neutrality emphasizing monitoring and mediation. London and Paris would stand by and refrain from mobilizing their troops provided that any forthcoming Russian military response was constrained, symmetrical to the threat, and remained purely defensive in spirit.

For a short while, both sides seemed to be taking the measure of each other, albeit warily. After a tense but relatively bloodless summer, on October 4, 1853, Turkish troops began a two-pronged offensive. They started with what amounted to a series of minor attacks along the Danube line. But a major conflict soon developed in the Caucasus Mountains, where the Turks threw everything they had into pushing the Czars’ troops back across the disputed frontier.

The Turks caught the Russians off guard, and by sheer weight of numbers, managed to force the Russians to pull back. Buoyed by this success, the emboldened Abdulmecid ordered his troops to press on, harrying them into the birch forests of Russian Georgia with a view toward reclaiming Turkish honor and then beating a path toward the peace table to settle the border question in his favor before his momentum, munitions, money, and luck ran out.

Meanwhile, the czar chafed at the restraints placed upon his legions but muted the rattling of his Cossacks’ sabers,with the result that by month’s end the whole of the Russian Caucasus Corps was under the threat of a potentially humiliating encirclement. Eager to close that trap, the sultan sent a supply convoy of transport steamers escorted by several frigates scurrying across the Black Sea to bolster his forces. This convoy managed to get through, thoroughly galling the Russians, who resolved that it would be the last.

To that end, a Russian squadron came roaring out of its base at Sevastopol on Russia’s Crimean Peninsula. Fifty-one-year-old Admiral Pavel Nakhimov, a veteran naval officer, commanded the Russian squadron. He planned to send any such future convoys straight to the bottom of the Black Sea.

One month later, an anxious Abdulmecid, oblivious to the beefed-up Russian presence, ordered up a second, more muscular convoy to be supported by several ships of the line to resupply his increasingly rickety offensive. Fearing a widening of the conflict, British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe, who had been keeping tabs on the developing situation in an effort to contain and control it, insisted that the sultan scale back the firepower escorting the supply ships to a handful of much smaller frigates.

Abdulmecid reluctantly agreed, even though he had already lost a brace of ships that month, the Medzhir Tadzhiret and her sister steamer, the Pervaz Bahri, boarded and captured within sight of the Anatolian coast after being quickly overwhelmed by Russian ships of the line. Thus, a much less brawny flotilla duly set sail that November to resupply the Turkish army, already beginning to bog down in the Caucasus. That flotilla was under the command of the venerable Patrona Pasha.

By that time, the Russian squadron was prowling the Black Sea waters hungry for a kill. Indeed, the czar put so many vessels on the water that he had all but attained supremacy of the great waterway. Nevertheless, the weather was so miserable and punishing to any who dared to test the Black Sea in autumn that the Russians, Nakhimov included, were continually compelled to return to port for refitting. The same Novem- ber gales that had battered Osman Pasha’s flotilla into submission were also having their way with their would-be pursuers. By the end of November, Nakhimov was down to three ships of the line, one frigate, and a lowly steamer to doggedly continue his interdiction mission.

Nevertheless, eagle-eyed lookouts aboard Nakhimov’s gargantuan flagship, the Imperatritsa Maria, caught sight of Osman Pasha’s ensign fluttering in the breeze high atop the Auni Allah, which was at anchor in the harbor at Sinop with the rest of his flotilla in the last week of November. Gazing hard at them through his spyglass, Nakhimov could hardly believe his eyes. From his perch on the Imperatritsa Maria’s quarterdeck a few leagues out to sea, they looked like a colony of basking sea cows wait- ing for the sun to come up.

Resolving to keep his quarry bottled up, Nakhimov stealthily deployed his squadron on the far outskirts of the harbor’s entrance. He arranged his ships in a horseshoe-shaped configuration designed to blockade the enemy ships. He then sent his immediate subordinate, Rear Admiral Fyodor Novosilsky, dashing off in his frigate to Sevastopol to scrounge up more firepower. Novosilsky dutifully returned on the last day of November with an additional half dozen ships andthepromiseofstillmoretocome.

Osman Pasha’s lookouts spotted Nakhimov’s squadron soon after it began fanning out just beyond the entrance to the harbor. But Osman Pasha ventured that the enemy would not dare to come any nearer because Sinop, picturesque little harbor town though it was, was nonetheless a fortified one, boasting several cannons designed to blast the hulls out of any potential attacker.

But there was one more detail that convinced Pasha to sit tight in the harbor that day. Having been in the Navy since the 1820s, he was decidedly old school. As a dyed-in-the-wool naval traditionalist, the idea of large fighting ships attacking vessels that were smaller than their own and of a different, lower class was considered dishonorable in the extreme. In his world, such things simply were not done.

Likewise, a gentlemen could never bring himself to do anything as low and as dastardly as attack a ship resting at anchor. In truth, most of the navies in the world still adhered to this chivalrous code. But it was about to become painfully clear that Nakhimov was no gentleman.

By November 30, Nakhimov had cobbled together an attack force composed of six ships of the line, two nimble frigates, and three workhorse steamers. Each was appropriately fitted out and battle ready. His command boasted more than 700 guns and enough cannon balls and shot to make mincemeat out of Pasha’s command, which owing to the meddling of Queen Victoria’s ambassador, consisted of seven small frigates, three corvettes, and two rusty support steamers.

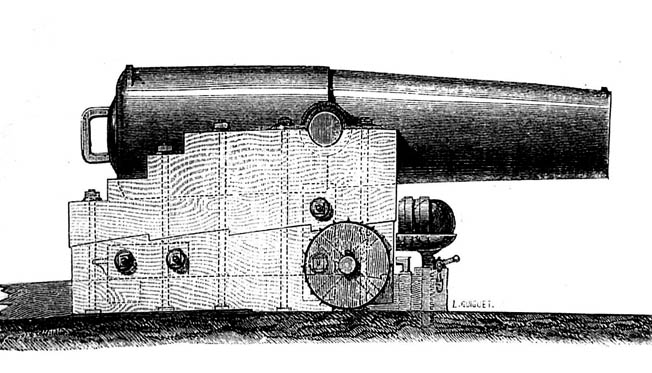

But Nakhimov’s squadron had one more item in its arsenal. Nakhimovs’ ships of the line were also equipped with a revolutionary new addition to their armament, a breakthrough in weapons technology that gave them a decidedly more lethal capability at sea than had ever been seen before, known as the Paixhans gun.

Named for its inventor, Frenchman Hans-Joseph Paixhans, the Paixhans gun was a heavy-duty, extended-range artillery piece that was originally intended exclusively for armies fighting on dry land. Unlike traditional smoothbore, bronze cannons, Paixhans guns fired shells with ignitable, delayed fuses. This unique innovation proved to be even more fearsome upon the high seas.

Rather than exploding on impact, the Paixhans shells would remain intact as they struck the sides of the wooden sailing ships of the day, penetrating and lodging themselves deep within the timbers of their vulnerable wooden hulls. When the fuses burned down the shells exploded, causing massive structural damage as they sent sheets of flame and burning chunks of metal whizzing through the air, shredding anything in their path.

Adapting this new technology for naval warfare was a Russian innovation. It was such a recent development that the Russian Navy had not yet deployed its newest gun in a sea battle.

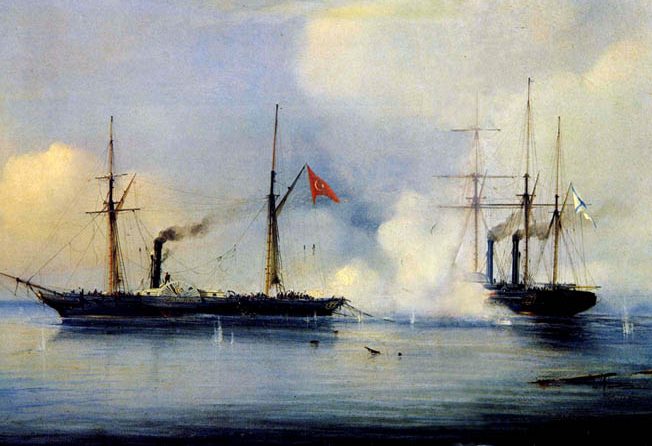

At about 12:30 PM, November 30, 1853, the impetuous Nakhimov could no longer contain himself. From the quarterdeck of the Imperatritsa Maria, he stared at his quarry and directed his gunners to prime her 84 guns. A moment later, signal pennants relayed his single, brusque command throughout the squadron: prepare attack.

With that, Nakhimov’s squadron maneuvered swiftly into position. Assuming a textbook triangular formation, they went forward, coming in hard from the northwest, sailing straight into the harbor with Nakhimov’s flagship in the van. As the Turks looked on in astonishment and horror, Nakhimovs’ six enormous Russian ships of the line moved in for the kill.

Forming into two long columns, they fanned out trimly across the harbor from left to right, facing off opposite Osman’s flotilla while simultaneously blocking their avenues of escape. By this bold if simple maneuver, Nakhimov also managed to deftly see to it that the Turkish ships were now anchored between his squadron and their own shore batteries, essentially neutralizing their offen- sive capabilities by making it impossible for them to open fire without hitting their own ships.

Dropping anchor, Nakhimov stood unperturbed on his quarterdeck as the Auni Allah loosed a single cannonball toward the Imperatritsa Maria, which, on Nakhimov’s command, gave the Auni Allah immediate reply and commenced firing, emptying a broadside into her.

Dropping anchor almost simultaneously, the Russian gun crews aboard the other ships of the line, the 84-gun Chesma and her sister ship, the Rotislav, and the 120 guns each aboard the Parizh, Tri Sviatitelia, and Veliky knyaz Konstantin, opened up on the doomed Turkish flotilla.

In one horrendous half hour, the harbor at Sinop began to resemble a butcher’s yard as the brutally efficient Paixhans guns found their mark time and again. Singled out for destruction, the Auni Allah was run aground, shot to pieces, and set on fire as she tried to cut the cables and run for it. Attempts to put out the flames came to naught. Incendiary shells continued to rain down upon her terrified, nearly helpless crew, bursting into flames amid hailstones of shrapnel that killed and maimed sailors and officers alike, including Pasha, whose left leg was completely shattered.

Having reduced her opposite number to a burning hulk, Nakhimov’s flagship then set its sights on the Fazli Allah, like nearly all of the Pasha’s ships a lowly frigate whose 44 guns were among those returning fire but were no match for the Russian Goliaths. Her fate was identical to that of the luckless Auni Allah.

At this point, the two Russian frigates, Kagul and Kulevtcha with 98 guns between them, began pounding away at the flotilla while the six ships of the line let their guns cool. The frigates blasted the hull out of the Damiat, which sank up to her gunwales, and the Nizamieh, which was run aground on purpose after having two masts shot away as she desperately tried to maneuver out of the kill zone and reach the open sea. Even the Russian steamers Khersones, Odessa, and Krym, which were there to support the attack, got into the fray.

The Paixhans guns found their mark yet again, blazing away at another Turkish frigate, the Navek Bahri, which was lifted clear out of the water in a spectacular series of explosions before sinking into the silt bed of the harbor. The smaller corvette Guli Sephid met an identical fate. The Turkish frigate Nessin Zafer ran aground after she broke her own anchor chain and was nearly pulverized. Yet another frigate, the Kaid Zafer, met a similar fate, as did the corvettes Nejm Fishan and Feyz Mabud and the steamer Erkelye. When they were done shooting at the ships, the Russians gleefully trained their guns on the shore batteries.

Alone among Osman Pasha’s decimated command, the humble steamer Taif was miracu- lously able to escape the carnage, slipping her anchor and clearing the harbor while the Russians were otherwise occupied. She limped through the Dardanelles and reached Constantinople two days later, living to tell the tale of what had happened at Sinop, where the Russians, with minor damage to three ships and a minimal cost of 37 killed and little more than 200 wounded, sent more than 3,000 Turkish sailors to a watery grave and bagged more than 300 prisoners, including the severely wounded commander of the Turkish squadron.

For the once unassailable Turkish Empire, the Battle of Sinop, occurring in the Black Sea, a body of water once so thoroughly dominated by Turkish sea power that successive dynasties in Constantinople had long since grown accustomed to thinking of it as a virtual Ottoman lake, altered the course of history. This black day on the water brought with it the sickening realization that the continuing, centuries-long decline of Turkey’s once mighty empire had just entered a new deadly phase.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments