By Viktor Kamenir

From his position opposite the left wing of the Teutonic Knights, Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas watched closely as the Teutonic Order redressed its lines at mid-morning in the already sweltering summer sun. Spotting a weakness in the enemy’s line, Vytautas signaled for his fast-moving Tatar cavalry to sweep forward from the hills west of the Marozka River.

Emerging from the treeline, Vytautas saw that some of the Teutonic Order units were still maneuvering as they redressed their lines. Intending to catch the enemy flat footed, Vytautas launched the Tatar cavalry under Jelal al-Din at the left flank of the Teutonic Knights.

The Tatar riders on their small, shaggy horses quickly covered the distance between the opposing armies. Either because the morning rain dampened the gunpowder or due to the speed of the Tatar charge, the Teutonic Knights had time to fire two cannon volleys before the Tatars were upon them. The desultory artillery fire emptied a few saddles but not enough to adversely influence the charge. The steppe riders quickly sabered the gunners and their infantry supports. They then focused their full attention on Grand Marshal Friedrich von Wallenrod’s Teutonic banners.

For almost an hour, the lightly armed Tatars darted back and forth around the Teutonic ranks attempting to detect and exploit a weakness. They peppered the Prussians with arrows and used lassos to dismount a few knights; however, the solid ranks of heavy Teutonic cavalry remained unbroken.

Because Vytautas’s initial assault had not dented the wall of Teutonic Knights, he had no choice but to feed his own troops into the battle. As the morning wore on, troops on both sides became engaged along the entire length of the battle line.

Samogitia. At the turn of the 15th century the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was the largest country in Europe. Stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, it encompassed all of modern-day Belarus, the majority of the Ukraine, and a significant part of western Russia. In the process of its expansion, it dynastically connected to all the ruling houses of Eastern Europe.

Between 1381 and 1392, two descendants of the Gedeminas dynasty, first cousins Jagailla and Vytautas, fought two civil wars for the throne of Lithuania. The struggle resulted in Jagailla firmly securing his position as the Grand Duke of Lithuania.

Thirty-five-year-old Jogailla converted to Christianity in 1386 and married 12-year-old Jadwiga, the reigning Queen of Poland. While jointly ruling Poland with her as King Wladyslaw II Jagiello, he retained the title of the Grand Duke of Lithuania as well, bringing the two states into a personal union. The two cousins reconciled in 1392, with Vytautas becoming the Grand Duke of Lithua- nia, while Jagiello received the nominal title of Supreme Duke. Jagiello formally granted Vytautas independence in 1401.

Reconciliation between Poland and Lithuania was viewed with extreme concern by the Teutonic Order. The two states were hostile to the Order, and Lithuania’s conversion to Christianity removed the reason for the Order’s crusade against the pagans.

When an uprising against the Teutonic Order flared up in Samogitia in May 1409, both Vytautas and Jagiello overtly and covertly supported the Samogitian cause. A small number of Lithuanian warriors operated among the Samogitian forces, while the Polish crown provided funds to purchase weapons for them. Teutonic Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen frequently questioned the sincerity of Vytautas’ and Jagiello’s conversion to Christianity and considered them secret pagans. Vytautas being a vassal of Jagiello, the grand master haughtily demanded that Jagiello put a stop to Vytautas’s interference, threatening to attack Lithuania. Jagiello replied that any attack against Lithuania would result in a Polish attack against Prussia. Precipitously, the Teutonic Grand Master declared war on Poland and Lithuania on August 6, 1409.

Neither side was ready for war. After sporadic fighting in the Dobrin District and Samogitia, an armistice was signed on October 8. Mediated by King Wenceslas VI of Bohemia and King Sigismund of Hungary, the armistice was to continue until St. John’s Day, which fell on June 24, 1410.

The opponents used the time to prepare for war and gain allies, an endeavor in which the two cousins were much more successful. King Jagiello secured the assistance of Mazovian dukes, while Vytautas obtained promises of neutrality from his son-in-law Duke Vasily I of Moscow. The Duchies of Moldavia and Pskov, as well as the Republic of Novgorod, promised military help. In contrast, despite von Jungingen’s best efforts, he was able to obtain only vague promises of military help from Kings Wenceslas and Sigismund and had to rely on guest knights and mercenaries to supplement his forces.

In December 1409, Jagiello and Vytautas held a secret meeting where they developed plans and goals for the upcoming campaign. Instead of fighting separate campaigns on two fronts, the objective of the campaign was to unite the two armies and strike for Marienburg Castle, the heart of the Teutonic Order, which was located in northern Prussia. To divert attention of the Order from the direction of the main thrust, small detachments of Lithuanians were to operate in Samogitia in the northeast while the Poles would make moves toward Pomerania in the west.

Taking into consideration the history of hos- tility between Jagiello and Vytautas, von Jungingen was doubtful that the alliance between the two cousins would hold. He completely misjudged the sincerety of the reconciliation between the two offspring of the Gediminas dynasty. Unsure of the direction of the main threat, the grand master garrisoned the border castles and staged the Order’s field army in a central location at Schwetz ready to rapidly shift to any point on the border.

On June 27, 1410, the army of the Polish Crown under King Jagiello arrived at the staging area at Czerwinsk on the Vistula River, roughly 30 miles northwest from Warsaw and 50 miles east of the Prussian border.

Neither Poland nor Lithuania had a standing army, and once the war was declared, noblemen, clergy, and some municipalities were obligated to provide armed contingents equipped at their own expense. The main building block of the Polish-Lithunian military, as well as that of the Teutonic Order, was a banner, similar in size and function to a modern battalion.

A total of 18,000 men fighting under 51 banners gathered under Jagiello’s direct command. Twenty-six were raised by prominent noblemen and clergymen of the kingdom, 18 banners were territorial, three banners were composed of Czech mercenaries from Bohemia and Moravia, three banners were from the Mozovian duchies, and one banner was from the Duchy of Moldovia. The majority of this force consisted of cavalry levy from the nobility, with infantry typically supplied by municipalities.

While the combat quality of individual Polish banners varied, three of them could be classified as elite. Two of the elite were the royal banners, the Nadworna (Household) and the Goncza. The former banner was composed of the members of the royal court. The latter banner, which was composed of young knights and derived its name from the Polish word gonitwa, meaning chase or pursuit, had the mission of acting as army’s vanguard, opening the battle and conducting pursuit. Another exceptional banner, the Great Banner of Krakow, included some of the best knights in Poland.

Individual banners were made up of 50 to 120 lances. Each lance was composed of a lance carrying armored knight and three to seven armed retainers, armed and equipped at the knights expense. The quality of the arms and armor depended on a knight’s income. The number of men in a lance and the number of lances in a banner varied. With Jagiello’s 18,000 men organized into 51 banners, a common Polish banner appeared to have averaged approximately 350 warriors. Not all banners being equal in size, they were balanced out by combining smaller banners into one. On campaign, each knight was responsible for providing his own supplies, and the large number of wagons required slowed the progress of the army. However, during the battle these wagons typically formed a wagenburg, a mobile fortress, to protect the camp in the rear of the fighting lines.

After inspecting and organizing his forces, Jagiello crossed the Vistula River on July 2. In a carefully timed and executed maneuver, Grand Duke Vytautas joined him with the Lithuanian army later the same day with 40 banners. Thirty-seven of Vytautas’s banners were composed of Lithuanians and Ruthenians with a small number of Samogitians. The remaining three banners consisted of Russians from the Duchies of Smolensk and Pskov and the Republic of Novgorod. The men of Novgorod were led by Lengvenis, Jagiello’s younger brother. Vytautas’s banners, totaling roughly 11,000 men, averaged approximately 275 soldiers each. In addition, the exiled Khan Jelal ad- Din of the Golden Horde brought close to 2,000 Tatars riders, seeking Lithuania’s support in his struggle to regain his throne.

On July 3, the combined Polish-Lithunian army moved north toward the Prussian border. The Tatars and Lithuanians, not knowing they were still in friendly Polish territory, began looting, killing, and burning.

The allies crossed the vaguely defined Prussian border six days later. Moving through Prussia like a swarm of locusts, the progress of the advancing army was marked by smoke rising from destroyed settlements. Barbaric Tatars were commonly blamed by Polish historians, but the Poles and Lithuanians share responsibility for the atrocities. Jagiello attempted to rein in the wholesale carnage. In Lautenburg, the king ordered two Lithuanian looters to build a gallows and then hang themselves in front of their comrades. Still, the outrages continued.

Teutonic Grand Master von Jungingen soon understood the allied maneuver toward Marienburg. Knowing the territory, he determined that the most likely location to cross the last river obstacle, the Drewenz River, on the way to Marienburg was at the village of Kauernik. Leaving 3,000 men under Magistrate Heinrich von Plauen at Schwetz to guard against the Polish forces at Bydgoszcz, the grand master rushed to Kauernik with his main army.

Von Jungingen arrived at Kauernik in plenty of time to fortify the fords by building stout wooden stockades to protect the beachheads on both sides of the river. With a strong castle on the nearby hill, the obstacles were defended by infantry, and cannons were positioned on the hills above the river crossing.

The force gathered by the grand master numbered approximately 20,000 men organized in 50 banners, averaging 400 men to a banner. A lance of the Order was composed of one knight and up to seven men, typically mounted crossbowmen. Roughly half of the force consisted of soldiers of the Teutonic Order and those of the lay knights living in the lands of the Order, but not members of the Order themselves. The other was composed of guest knights and mercenaries. King Sigismund of Hungary sent a token force of 200 fighting men and several hundred Genoese mercenary crossbowmen. Similar to the Polish-Lithunian army, the majority of the Order host was cavalry.

After conducting several probes, Jagiello called for a military council. Weighing their options, the members of the council decided not to attempt a river crossing in the face of such a strong posi- tion. Instead, on July 11 the allied army turned east toward the headwaters of the Drewenz River, intending to bypass the difficult terrain.

The Order army moved east as well, shadowing Jagiello’s forces along a parallel route. Even though Jagiello’s army consisted largely of cavalry, the advance along the narrow roads leading through dense forests was slow owing to the large number of supply wagons.

On July 13, the Polish-Lithunian army destroyed the Teutonic garrison at Gilgenberg then sacked and burned the town “[Jagiello] went toward Gilgenberg and took that city and burned it, and they struck dead young and old and with the heathens committed so many murders as was unholy, dishonoring maidens, women, and churches, cutting off their breasts and torturing them, and driving them off to serfdom,” wrote Prussian chronicler Johann von Posilge. They also desecrated the churches.

The blood of the innocents demanded vengeance, and the Teutonic grand master chose the village of Grunwald as the location to exact retribution from the invaders. Arriving there in the afternoon of July 14, the grand master studied the area. The battlefield chosen by von Jungingen was a roughly triangular area of approximately two square miles, hemmed in by woods and thevvillages of Grunwald, Tannenberg, and Ludwigsdorf. Its rolling, sparsely wooded terrain was bisected by a shallow valley with a small creek running at the bottom of it. Whichever side intended to attack would have to descend into the valley, cross the boggy field, and charge uphill.

The allied army arrived in the evening of the same day and set up three separate camps less than four miles away near Lake Lubian. The Polish camp was near the southern edge of the lake by the village of Faulen, the Lithuanians in the middle, and the Tatars to the north of the lake. With the opposing pickets keeping a wary eye on each other, the night passed uneventfully.

The sun came up shortly after 4 AM on July 15, and the day promised to be a hot one. After an early mass, the army of the Teutonic Order arrived on the field at approximately 6 AM and deployed on a northeast-southwest axis in three distinct bodies along a roughly southwest-northeast axis. On the Teutonic right, behind the village of Ludwigsdorf, were 20 banners under Grand Commander Kuno von Lichtenstein. On the Teutonic left, anchored on the village of Tannenberg, were 15 banners under Grand Marshall Friedrich von Wallenrod. Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen established his command post on the hill behind the center of the Order’s deployment with 15 banners in reserve. The fortified camp was located farther back near Grunwald.

The forces directly under von Jungingen and von Lichtenstein were the best disciplined troops of the Order. Grand Marshall von Wallenrod commanded forces of lesser quality, composed largely of banners of mercenaries, guest knights, lay knights, and Polish vassals such as Duke Casimir V of Pomerania. To compensate for the qualitative weakness of von Wallenrod’s command, the major- ity of the Teutonic Order’s small number of artillery pieces and infantry seemed to have been deployed on the left flank where they were screened by detachments of heavy cavalry.

It is possible that knowing the locations of the allied camps, von Jungingen assumed that the allied forces would take to the field relative to their camp sites, the Polish to the south and Lithuanians and Tatars to the north. Therefore, he deployed his best troops against Jagiello and his less reliable ones against Vytautas.

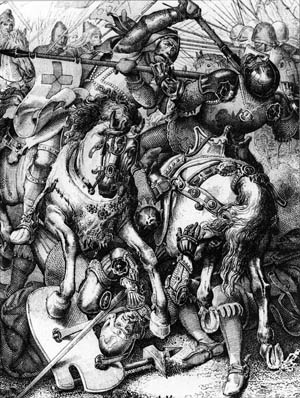

The banners of the Teutonic knights and soldiers presented a rather uniform appearance, their unit cohesiveness and discipline strengthened by monastic vows of obedience. Professional warriors of the Teutonic Order were divided into three classes. The noble-born knight-brothers, wearing their distinctive white capes with plain black crosses, were the shock troops of the Order, equipped with full plate armor and mounted on heavy war horses. The principal weapon of a knight was a heavy lance, supplemented by swords and maces. Of all the forces of the Order at Grunwald, only 250 were full knight-brothers.

The half-brothers, also noble-born, were those not willing to take the full long-term monastic vows of the knight-brothers. Equipped and armed similar to the knight-brothers, they wore light- gray capes with a black Greek capital letter Tau (T) combined with a family coat of arms.

The sergeant-brothers, who were of humble birth, wore light gray capes with a black Greek capital letter Tau minus the coat of arms. Typically equipped with chainmail armor, they were the light cavalry of the Order. A banner of the Teutonic Order itself would have the Order lances as its core, rounded out by lay knights, town levies, and mercenaries.

In contrast to the core banners, additional troops of the Order presented quite a colorful and varied appearance, greatly varying in quality and quantity within a banner. The lay knights were the nobility living in the lands of the Order but were not members of the Order. The quality of their arms and equipment, as well as the number of armed retainers, varied greatly based on their income. The lances of guest knights, as well as the mercenary ones, varied in quality. According to the records of the Order, 1,237 mercenary knightly lances, with at least three men per lance, were present at Grunwald.

Rounding out the forces of the Teutonic Order were the town and village militia and native levies, typically all infantry armed largely with crossbows and polearms. While some could afford good arms and armor, the overwhelming majority of them were lightly or poorly armed.

The professional Teutonic knights were confident of victory, justly considering themselves the best warriors of Christendom. The knightly banners were deployed not in continuous lines, but lines of columns with wide spaces between the columns. Each column was headed by a wedge of heavily armed and armored knights. Nicknamed “the boar’s head,” the wedge had three knights in the first rank, five in the second, seven in the third, nine in the fourth, and 11 in the fifth and the following ranks. The stan- dard bearer, protected by picked warriors called antesignani, was placed in the first rank of the column behind the wedge.

As the sun climbed higher in the morning sky, the allied army remained in its camps. A brief and intense rain was followed by rising temper- atures, and the Teutonic army, standing under arms and in full armor since 6 AM began to feel the effects of the heat.

Advised by their scouts that the Teutonic army was in the field, the two allied comman- ders reacted differently. Jagiello, a careful, intelligent, politically astute sexagenarian and a sincere convert to Christianity, attended a mass. In contrast, his fiery and energetic younger cousin Vytautas, who was the more experienced soldier, wanted to immediately deploy for battle.

But Jagiello would not give the command to proceed. In vain, Vytautas appealed to him in person and through messengers, requesting permission to exit the woods and attack the enemy. Finishing one mass and starting another, Jagiello gave orders to advance the army only to the edge of the woods on their side of the valley. Only after attending the second mass, did Jagiello don his armor and go forward into battle.

Arriving at the edge of the forest, Jagiello saw that the Order forces were deployed too close to his treeline. Exiting from the forest in disorder and attempting to maneuver to form battle lines so close to the enemy would have been inviting disaster. Still procrastinating, Jageillo began a lengthy process of knighting several hundred of his warriors.

In order to goad Jagiello into action, von Jungingen sent two heralds to him. Approaching the king under the flag of truce, the heralds threw down two naked swords, sticking them into the ground. A sword presented as a gift was delivered sheathed in its scabbard. To deliver a naked sword was a challenge to a fight. Impaling a naked sword into the ground in front of the recipient meant a fight to the death.

“The Grand Master sent two swords to us with the following announcement: ‘Know you, King and Vytautas, that at this time we will fight you,” wrote Jagiello. “For this, we are sending you two swords to assist you.’ We replied: ‘We accept the swords. You are sending them to us in the name of Christ, before him your obsti- nate pride must bow, we will give you a battle.’”

As soon as the two heralds had returned to their side of the valley, the Teutonic battle line moved back several hundred feet. The move unmasked their cannons. Only at that time did Jagiello give his forces the order to exit the woods and form battle lines. The Polish banners formed the left flank of the allied line, near the village of Ludwigsdorf. The three elite banners, the Nadworna, Goncha, and the Great Banner of Krakow, took their place on the right center of the line. The three banners of Czech mercenaries formed the right flank of the Polish line. Jagiello, with his retinue, positioned himself on a knoll in the rear of the center of the allied position. A Polish reserve was farther to the rear near the village of Faulen.

Lithuanian forces deployed on the right of the allied line near the village of Tannenberg and effectively separated from the Polish banners by Jagiello’s hill. The three Russian banners, part of the Lithuanian forces, deployed on the left of the Lithuanian line and the Tatars under Khan Jalal al-Din deployed on the extreme right.

The armies lined up on the opposite sides of the shallow valley appeared remarkably similar. Since a majority of Polish nobles purchased armor imported from the Germanic states, the opposing knights looked the same, differentiated mainly by heraldic symbols. Difference in armor depended on an owner’s wealth, not national characteristics. Many of the heraldic symbols, due to the large number of ethnic Poles in the Order’s forces, were similar in color schemes and designs. Jagiello ordered his warriors to tie bunches of straw to their arms to differentiate the opposing sides.

The wealthy knights wore full plate armor or flexible brigandine armor made from small armor plates riveted to leather. The head was protected by a basinet helmet with a face guard. The most common of these was the hounskull helmet, which gets its name from the visor’s resemblance to the protruding muzzle of a hound. Less prosperous knights and men-at-arms wore mail with a helmet in the shape of a brimmed hat.

Due to eastern influences, Lithuanian and Russian warriors sported conical helmets worn with scale or lamellar armor over a mail hauberk. The Tatars commonly wore only padded jackets.

Just like its opponents, the Polish-Lithunian army was confident of victory. It had enjoyed a successful campaign so far and was well rested and supplied. The night before the battle Polish sentries saw patterns on the moon, which they interpreted as the good omen of the king striking down a monk.

Vytautas’s attempt to catch the Teutonic knights flat-footed with his initial assault failed despite the best efforts of the Tatars. Wallenrod ordered a counterattack by several banners. The heavily armored Teutonic Knights easily overwhelmed the Tatars, who broke and retreated in an apparent panic.

Vytautas sent forward several Lithuanians banners and they were disordered in turn by the heavy cavalry of the Order. Both Wallenrod and Vytautas fed more and more banners into the fray. During the heavy fighting a vassal banner of the Teutonic Order gave ground and began to retreat, but it rallied. The grand master ordered the regrouped troops to join his reserve, which raised it to 16 banners.

However, the lightly armored Lithuanians and Tatars could no longer withstand the press of the Teutonic knights. The whole of Vytautas’s wing collapsed in a flight, hotly pursued by nine of Wallenrod’s banners. Only the three Russian banners maintained cohesiveness and began edging left to link up with the Czech banners of the left wing under pressure from Wallenrod’s remaining five banners. One of the Russian banners was cut off, surrounded, and annihilated, while the remaining two were able to link up with the Czechs.

The retreat of the Lithuanians and Tartars is variously interpreted as a panicked flight or a tactical retreat, largely depending on the nationality of the historian. The Polish historians largely interpret this as the wholesale collapse of the Lithuanian army. The Lithuanian scholars interpreted it as a feigned retreat.

Both versions have merit. The feigned retreat was a long-honored tactic of steppe peoples such as the Tatars. A portion of the total force would retreat, intending to draw the enemy into a pursuit. When the impetuous pursuers were disordered by the chase, they would be hit by fresh forces lying in ambush, while the fleeing Tatars wheeled around and hit the pursuers in their flanks. Vytautas was well familiar with this tactic, having barely survived a similar Tatar ambush in 1399 at the Battle of Vorskla River.

Most likely, the truth lies somewhere in the middle. It is quite likely that the Tatars attempted a feigned retreat, but the Lithuanian banners were not able to properly execute the ambush, leading to the collapse of the whole wing.

Pursuing the retreating Lithuanians all the way to their camp, many knights of the Order, including the majority of the guest knights, impetuously became scattered and disorganized while looting the Lithuanian camp. “The pursuing enemy, assuming that they gained victory, separated too far from their banners, but soon the roles reversed and they became pursued themselves,” writes the anonymous author of the Chronica Conflictus. When they tried to return to their own lines, the king’s men cut them off, killing some and taking the rest prisoner.

At approximately the same time as the Lithuanian wing started to give way, the first Polish line of 17 banners moved forward under the Grand Marshal of the Polish Crown Zyndram of Maszcowice. He was opposed by 20 banners under Grand Komtur Kuno von Lichtenstein.

This was a clash of evenly armed and armored opponents. A suit of plate armor weighed approx- imately 55 pounds, not much different than a combat load of a modern infantryman. Its weight was evenly distributed over the whole body and its articulated joints allowed a knight the freedom of movement. Wielding heavy weapons while wearing heavy armor, the men quickly became fatigued. A battlefield commander had to be a diligent choreographer to rotate units in and out of the front line.

At approximately 2 PM, Grand Master von Jungingen saw the hard-pressed and depleted Czech mercenaries and the Russian banners on the Polish right flank begin to give way. Judging the moment had come, von Jungingen led forward his reserve banners.

In a wide flanking maneuver, they looped through the battlefield debris of the abandoned positions of the Lithuanian army. Approaching from the right rear of the Polish position, the Teutonic counterattack was aimed directly at the hilltop position of the Polish king. The Polish, seeing units approaching from the rear, mistook them for returning Lithuanians. However, they were soon dis- abused of their mistake when the Prussians cut into their rear ranks. After a short, desperate fight, the Poles were able to turn their rear ranks to face the new threat and the balance was again restored.

A desperate fight flared up around Jagiello’s position. The standard bearer of the Great Banner of Krakow was cut down and the great flag fell to the ground. This gave a momentary infusion to German morale, but the flag was quickly picked up by another Polish soldier and raised high.

The king’s retinue circled Jagiello, and his personal banner was furled to hide his posi- tion. One Teutonic knight, Lupold von Kokeritz, suddenly recognized the king and fought through his bodyguards to get to him. Jagiello bared his sword, ready to meet the attacker, when his unarmed secretary Zbigniew Olesnicki picked up a broken lance and knocked the Prussian knight off his horse. The king’s bodyguards arrived just in time and fin- ished off von Kokeritz.

At this high tide of the Teutonic attack, the Grand Duke Vytautas brought the rallied Lithuanian banners back to the field. The 16 banners around von Jungingen became pinned between the Poles and the Lithuanians. Seeing a new threat, the Prussian banners under von Lichtenstein began to edge back. With the noose tightening around him, the impetuous von Jungingen refused to retreat. Grimly, the senior officers of the Teutonic Order and the remnants of reserve banners closed ranks around their grand master. With his men cut down around him, the grand master received wounds to his face and chest but continued fighting. However, he could not escape. He was mortally wounded by the thrust of a lance through his neck.

Seeing the grand master fall, the Teutonic banners still maintaining cohesion began falling back to their camp, intending to set up defenses around the wagenburg. However, the apparent security of the wagenburg became a death trap. The allied forces surrounded the surviving troops of the Order and methodically cut them down. It is believed that more of the Teutonic troops died in the camp than in any other loca- tion on the battlefield.

Following his jubilant troops, Jagiello entered the Order’s camp. As the king kneeled to give thanks to God for the victory, his victorious troops began looting the camp. A cheer went up when a large cache of wine barrels was discovered and the troops began breaking them open to celebrate their victory. Concerned that his men would drink themselves senseless and fearing a possible German counterattack, Jagiello ordered the wine barrels destroyed.

Some of the banners not engaged in the fight at the Order’s camp pursued the fleeing sur- vivors, capturing and cutting down thousands of them. The pursuit lasted for 10 miles, ending with nightfall.

On the morning of July 16, the bodies of von Jungingen and other senior commanders of the Teutonic Order were found. They were cleaned and sent to Marienburg where they were interred three days later. The bodies of nobles were buried in the church yard near the battlefield, while the commoners of both armies were buried in mass graves on the battlefield.

The losses of the Teutonic Order were stag- gering. Along with von Jungingen, four out of five senior officers of the Order lay dead on the battlefield. The fallen commanders were Grand Marshal Friedrich von Wallenrod, Grand Komtur Kuno von Lichtenstein, Grand Treasurer Thomas von Merheim, and Chief Administrator Albrecht von Schwartzburg.

Of the approximately 250 knight-brothers of the Order, 203 were killed and many more wounded and captured. Only 1,427 warriors returned to Marienburg, according to the Order’s pay records. More than 8,000 lesser knights, soldiers, mercenaries, and foreign vol- unteers perished and approximately 14,000 were taken prisoner. Those too poor or insignif- icant to merit ransom were released, but the prominent captives were held for ransom.

The allied losses were significant as well, with 5,000 killed and 8,000 wounded. These numbers are proof that, despite the disaster that befell them that day, the soldiers of the Teutonic Order gave a good account of themselves.

On July 17, the allies set off toward Marienburg. They advanced cautiously, expecting to be confronted again. But the majority of the Teu- tonic castles and towns surrendered without resistance.

Arriving in front of Marienburg on July 26 and expecting it to surrender, Jagiello discovered the strongest Teutonic Order castle was prepared for a long siege. Receiving news of the disaster at Grunwald, the Magistrate of Schwetz Heinrich von Plauen rushed to Marienburg with 2,000 men. He discovered a city in panic. The ragged survivors of the battle brought news of the slaughter and tales of allied atrocities. The only surviving senior officer, the Grand Hospitaler Werner von Testsingen, was in shock after the battle and did not wish to take command. Von Plauen, elected as the pro-tem grand master, energetically began preparations for the siege.

The slow progress of the Polish-Lithunian army gave von Plauen the crucial time to prepare for defense. He restored morale and discipline. He also issued orders for supplies to be stockpiled and weapons to be distributed to local levies. In addition, outlying garrisons were ordered to pull back to a safer location. The suburbs surrounding the fortress were burned and pulled down to deny the besiegers cover.

After an unsuccessful siege, the Polish-Lithunian forces withdrew in mid-September. Once the allied forces retreated, von Plauen took the offensive and quickly recaptured a majority of the territory. The two sides signed a peace treaty in February 1411.

Despite achieving significant success in battle, the allies gained very little territory. The Dobrzyn district was returned to Poland. Samogitia reverted to Lithuania, but only for the duration of Jagiello’s and Vytautas’s lifetimes. More damaging for the Teutonic Order was the cripplingly large reparation it was obligated to pay. The loss of the bulk of its army forced the Order to increasingly to rely on expensive mercenaries. New taxes and confiscation of wealth from churches needed to pay the reparation steadily undermined the capability, prestige, and power of the order. The wound delivered at Tannenberg was fatal to the Teutonic state, although it did not appear as such at first.

The Battle of Grunwald plays a significant role in the national identities of three modern coun- tries. In Lithuania, now a sliver of its former great state, it is referred to as the Battle of Zalgiris and the Grand Duke Vytautas, dubbed Vytautas the Great, is the national hero. The Germans call it the First Battle of Tannenberg, the second one being the annihilation of the Russian Army in 1914, a vindication for the defeat 500 years earlier. In Poland, the Battle of Grunwald is a revered symbol of Polish patriotism. The two swords haughtily delivered by the Teutonic heralds to King Jagiello and Grand Duke Vytautas became the royal insignia of Poland.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments