By Arnold Blumberg

On September 4, 1944, tanks of the British 11th Armored Division lumbered into the outskirts of Antwerp, Belgium. This was the crowning moment of the division’s spectacular six-day drive ordered by British XXX Corps commander, Lt. Gen. Sir Brian Horrocks, on August 30. Horrocks’ directive was intended to capitalize on that day’s crossing of the Seine River in hot pursuit of a thoroughly disorganized German army, decimated and on the run as a result of its defeat in the Normandy campaign of the past eight weeks.

At noon on the 4th, the “Black Bulls” of the 11th pushed into the city proper under orders from Horrocks to “go straight for the docks and prevent the Germans from destroying the port installations.” The need to capture Antwerp and the Dutch port city of Rotterdam had been recognized early in the Allied planning of the invasion of Western Europe. Now the first seemed likely to fall.

With a capacity to receive 40,000 tons of matérial a day, Antwerp was the largest port in Western Europe and was far closer to the armies advancing into Germany than Cherbourg, Le Havre, or the English Channel ports. But there was one major problem—it was 60 miles from the sea. No ship could enter it until its approaches were cleared. Capture of the harbor alone would not guarantee its use by the Allies. The Germans had to be prevented from destroying the port facilities and mining and blocking the estuary of the River Scheldt that flowed from the Channel past Antwerp. Nazi coastal batteries lining that waterway had to be eliminated before safe approaches to the river routes could be established.

By nightfall of the 4th, the British tankers had secured most of Antwerp’s vital dockyard but then stopped their advance, forfeiting the real opportunity of clearing the entire Antwerp area—including the Scheldt Estuary—and capturing the German Fifteenth Army defending the region while their adversary was disorganized and on the run.

After a dash of 230 miles from the Seine to Antwerp the men of the 11th Armored were exhausted and at the end of their supply line. On the 6th the Black Bulls made a halfhearted attempt to create a crossing over the Albert Canal north of Antwerp but were thwarted by determined German resistance under Lt. Gen. Kurt Chill, who had cobbled together a defense force from the remnants of the German 84th, 85th, and 89th Infantry Divisions and several understrength parachute battalions, a total of 3,000 men to defend the canal’s crossing points. Two days later the 11th Armored was ordered 40 miles to the east.

Fixed on reaching the German frontier by the fastest possible means, the Allied army commanders and Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force chief General Dwight G. Eisenhower entirely overlooked the strategic and tactical opportunity that had developed in western Belgium. Eisenhower believed that the “best opportunity for defeating the enemy in the West is to strike at the Ruhr and Saar” the industrial heart of Germany, and that their capture would cripple the country’s ability to continue the war. Further, Eisenhower felt that the forces currently opposing the Western powers were weak and disorganized and that the Wehrmacht was on the verge of collapse in the West, hence his broad front strategy of pressing the enemy along the entire line from the English Channel to Switzerland and racing for the Rhine River. With this mind-set, Eisenhower gave no attention to securing the Scheldt Estuary or closing the trap on the Fifteenth Army, which was fleeing the area. This shortsighted strategic focus set the stage for the brutal and prolonged battle the Canadian First Army would have to wage around Antwerp in the coming weeks.

If the Anglo-American high command failed initially to see the strategic importance of the Scheldt Estuary, the same could not be said of its opponents. The sudden appearance of the 11th Armored Division in Antwerp on September 4 sent a shudder of panic throughout the German chain of command. Field Marshal Walter Model, leader of the German forces in the West, ordered the southern elements of the Fifteenth Army to make a fighting withdrawal to the coastal fortresses of Boulogne, Calais, Dunkirk, and Ostend, while the rest of Fifteenth Army made a last ditch effort to secure an escape path eastward to Breda. The herculean efforts of General Chill and his men and the indifference of the Allied high command toward taking the area around Antwerp allowed the German Fifteenth and newly formed First Parachute Armies to organize a shaky defensive line from Antwerp to the Maas River by mid-September.

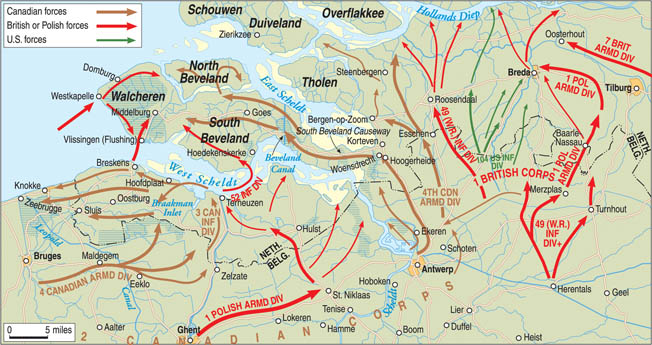

On September 8, the 4th Canadian Infantry and 1st Polish Armored Divisions of the First Canadian Army came up against stiff German resistance along the Ghent Canal west of Antwerp. Up to that date British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery, commander of the 21st Army Group, had given priority to opening the Channel ports, placing only secondary importance on the destruction of the enemy forces northeast of the Ghent Canal. At the same time the First Canadian Army’s zone of responsibility was enlarged to include Ghent and the south shore of the Scheldt to within a few miles of Antwerp.

On the 10th, Eisenhower, who had obliquely been pushing for the capture of Antwerp and the opening the Scheldt, agreed to hold off on that objective until Operation Market-Garden, the Allied land and parachute strike to the Rhine through Arnhem, was completed. Two days later the pressure to clear the Scheldt and thus alleviate Allied supply problems was increased when the Combined Chiefs of Staff stressed the need to do so “before bad weather sets in.” That same day Montgomery asked General Harry Crerar, the commander of the First Canadian Army, if he could tackle the problem.

While the Allied military hierarchy slowly came to terms with the issue of opening the Scheldt Estuary to friendly shipping, the Germans had been considering the issue since the tanks of the 11th Armored Division had entered Antwerp early in September. Adolf Hitler ordered Walcheren Island on the north bank of the Scheldt, along with the land communication to it, and the south bank of the estuary along the Albert Canal to the city of Maastricht to be defended to the last bullet. To create a proper defense, Fifteenth Army continued its retreat to the east and connected with the newly created First Parachute Army, establishing a blocking position along the Albert Canal east of Antwerp. Hitler’s directive put in motion 100,000 German troops whose task was to secure western Belgium including the Scheldt River region.

The German response to the threat posed by the Allied capture of Antwerp made the task of the First Canadian Army resemble, on a large scale, the reduction of a medieval fortress, a comparison that could be extended to the defensive problems facing the Germans. Fortress Walcheren, as designated by Hitler, was sited to defend a waterway at a vital crossing. South of the river its outer defenses were protected by a moat, the Leopold Canal. Its central “keep” was Walcheren Island itself. The land approach was a long-defended route: the south Beveland Peninsula with a series of gates, Woensdrecht at the base of the peninsula, the Beveland Canal, and finally the 1,000-yard causeway that joined the island to the mainland.

On the “other side of the hill,” Colonel General Gustav Adolf von Zangen, chief of Fifteenth Army who was responsible for the Scheldt-Antwerp area, faced two major problems: extricating his forces from south of the Scheldt River and shoring up the defenses east of Antwerp. By September 23, he had accomplished the first task before the Canadians could stop him. He then went about solving his second problem by placing a veteran infantry division to hold the south bank of the Scheldt and another positioned on the Beveland Peninsula and Walcheren Island. Supporting his foot soldiers as well as well as covering the sea approaches, Zangen sited a number of medium 75mm and a score of powerful long-range 105mm and 155mm artillery pieces in strong concrete emplacements. Topping off the German preparations was the accumulation of enough ammunition and food to sustain the defenders during a long siege.

Since the Normandy breakout in the summer of 1944, the First Canadian Army had protected the long Anglo-American left flank as it raced through France toward Germany’s western frontier. First Canadian Army was the most international of the Allied formations. Its Canadian Army troops included a mix of tank and infantry outfits ranging in size from battalions to divisions, and its II Corps was made up of one armored and two infantry divisions. The place of its I Corps, which was fighting in Italy, had been taken by British I Corps. The 1st Polish Armored Division had become almost a permanent fixture in the army. Also included in the army’s order of battle were Belgian, Dutch, and Czechoslovakian units.

Crerar was the first Canadian general to lead a field army in battle. Lt. Gen. Guy G. Simonds headed up II Corps, and Lt. Gen. John Crocker led I British Corps. While Crerar and Crocker were both competent officers, Simonds was a gifted combat soldier. When the battle for the Scheldt opened, First Canadian Army numbered about 150,000 men, 600 tanks, and more than 800 artillery pieces.

On September 13, Montgomery finally ordered Crerar to clear the land and sea approaches to Antwerp. Simonds had begun the effort the day before but feared the ground was unsuited for armored operations. He was correct; the number of water-filled canals and wet ground south of the Scheldt made the going slow, and resistance from the German defenders of the 245th Infantry Division was so fierce that it took units of the 4th Canadian and 1st Polish Armored Divisions until the 21st to clear the region south of the Scheldt of the enemy. With the Canadians butting up against the German defenses along the Leopold Canal, the next phase, cutting of the land routes to Walcheren Island to the east of Antwerp, began.

On September 19, II Corps, with the 4th and 1st Polish Armored Divisions leading, initiated a move 20 miles northeast of Antwerp to take the city of Bergen Op Zoom to isolate and attack South Beveland Island from the east. At the same time, British I Corps marched up on II Corps’ right and established contact with the British Second Army.

Meanwhile, the Canadian 4th Infantry Division, occupying Antwerp, fought to drive the Germans from their positions just east of the town across the Albert Canal, from where they continually shelled the city’s port. On the 22nd, elements of the division established a bridgehead over the canal at the village of Wyneghem east of Antwerp, forcing German defenders of the 67th Corps to abandon their posts. The next German defensive stand at the Antwerp-Turnhout Canal was overcome on the 23rd when the 2nd Canadian and British 49th Infantry Divisions established a bridgehead over that obstacle.

On September 27, new orders came down from Montgomery’s 21st Army Group headquarters to free up British Second Army’s left flank for a move toward the Ruhr. The Canadians had to maneuver 40 miles east of Bergen Op Zoom to cover the British left. Simonds had no alternative but to send the Poles and 4th Armored northeast since these new orders showed Montgomery was still giving the opening of Antwerp low priority.

Montgomery’s continued lack of concern for clearing the Antwerp-Scheldt area stemmed from the debacle of Operation Market-Garden (September 17-26). The failure of Market-Garden forced him to shift formations from the First Canadian and Second British Armies away from the task of seizing the Scheldt and instead send them east to guard the Nijmegen salient. As a result, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, recently attached to British I Corps, was given the job of sealing off the South Beveland Peinsula.

By now no one in the First Canadian Army was under any illusion about the enemy’s ability and determination to fight. Though short on equipment and understrength in manpower, most German units showed steadfastness in defense and a willingness to deliver sharp counterattacks. Referring to the fighting at the Albert Canal, the war diary of the 5th Brigade, 2nd Canadian Division noted: “This was the first time our troops had met the enemy using bayonets.”

On the 28th, the 2nd Division took the town of St. Leonard about 15 miles east of Antwerp. Three days later it took nearby Brecht and held it despite constant mortar bombardment and several counterattacks. Polish armor and foot soldiers of the 49th Division were then ordered to break out of the bridgehead on the Antwerp-Turnhout Canal to the northeast with the 49th aiming for Merxplas and the Poles driving for Tilburg along the rail line out of Turnhout. The Germans reacted by canceling their proposed strike at the Nijmegen salient, sending Kampfgruppe Chill (General Chill’s ad hoc battlegroup) to Baarle Nassau east of Antwerp to defend the Tilburg area against the Poles. Although a determined assault by Chill’s men in conjunction with the 719th Infantry Division, 67th Corps did not succeed in driving the Poles back. Polish losses were severe.

On October 4, Antwerp was finally cleared of Germans. Five days later the British I Corps halted to refit and reorganize. The Canadian 2nd Division returned to the control of Canadian II Corps, while General Crocker was given the British 7th Armored and 51st Infantry Divisions. Two days prior, the 4th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Division moved within three miles of Woensdrecht at the eastern base of the South Beveland Peninsula.

Early on a warm October 7, the 5th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Division passed through its sister 4th Brigade on the way to Woensdrencht with the object of sealing off the South Beveland Peninsula. The division’s 4th Brigade was sent to the rear, while its 6th Brigade screened the division’s right flank back to Brecht. The area was studded with flooded polders rising inland to sand dunes and heathland, with groves of pine and spruce trees all around. As opposing machine-gun fired opened up, companies fought their way into the village of Hoogerheide just east of Woensdrencht, engaging in bitter house-to-house fighting. By dark the town had been taken along with 61 German prisoners. Farther north, other Canadian units had been stopped at the hamlet of Korteven.

The next morning, the 5th Brigade commander was informed by two civilians that a group of 2,000 German infantry supported by eight tanks was preparing to assail the Canadians. These turned out to be the 6th Parachute Regiment of Chill’s Kampfgruppe, which had been diverted to the threat developing near Woensdrencht. The German airborne troops were fighting as infantry and had orders to reoccupy Hoogerheide and then move south to Ossendrencht.

During an early afternoon probing attack, the Germans lost a PzKpfw. V Panther medium tank. The first heavy German attacks took place in the evening but were beaten back. On the 6th, the entire 6th Parachute Regiment struck the Canadian left. The effort was thrown back with the loss of two Nazi tanks and a number of infantry casualties. The Canadians counterattacked with a mixed infantry-tank force capturing a wood that overlooked their position. This action netted 31 prisoners.

Later that afternoon, the Germans drove a Canadian infantry company from the outskirts of Woensdrecht. Parts of Hoogerheide were captured by the Germans but retaken. On October 9, Canadian tanks, after pushing onto the Woensdrecht rail line, were repulsed by German tanks and self-propelled guns. The German moves succeeded in keeping open the gate to the Scheldt fortress and its link with the German 70th Infantry Division in South Beveland and Walcheren. On October 2, the Canadian 4th Division had loaned an armored regiment and an infantry battalion to the 2nd Division to protect its open right flank. Although these reinforcements allowed the 2nd Division commander, Maj. Gen. A.B. Matthews, to augment the force attacking the neck of the peninsula, the odds were still not in his favor.

On October 10, the Royal Regiment of Canada, 4th Canadian Brigade picked its way across the sodden polder terrain southwest of Woensdrecht and reached the railway that ran along the isthmus but were not able to cut the highway beyond and parallel to it. As a result, in an operation code-named Angus, the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment), 5th Brigade, 2nd Division was directed to block the rail and road lines near Woensdrecht.

Three days later, during daylight and under cover of friendly artillery, two companies of the Black Watch charged over 1,000 yards of open ground flanked by dikes filled with enemy soldiers. Hit by a hail of machine-gun and artillery fire, their attached tanks unable to keep up due to the flooded ground, and the infantrymen unable to see to fire due to foggy conditions, the Black Watch attack was stopped after two hours. A second effort was made late that day with the same devastating results. German counterattacks with tanks and infantry continued, some resulting in hand-to-hand fighting and firing at point-blank range. The futile attacks cost the Black Watch 183 men killed, wounded, and missing, and the day came to be known as Black Friday to the infantry of the 2nd Division.

After the October 13 attacks it became obvious that the only way the 2nd Canadian Division would be able to break the road link to the Scheldt was to take the high ground around the village of Woensdrecht. From those low hills the Germans could see everything that moved on the bare fields below, which formed the neck of the peninsula. On October 16, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry Regiment, 4th Brigade, supported by 168 artillery pieces and tanks, made a night attack capturing Woensdrecht.

During mid-morning the German 6th Parachute Regiment counterattacked and overran the right flank forward company of the Hamiltons. With the Canadian position in grave danger, a hurricane of friendly artillery fire was ordered down on the threatened sector. Caught in the open, the Germans were annihilated within five minutes.

For the next five days the Hamiltons continued their battle for Woensdrecht, beating off German attacks and ferreting out enemy snipers who lurked in the ruins of the village. The eventual Canadian victory cost them 167 dead.

For the moment the 2nd Division lacked the strength to do more than hold its hard-won gains and wait for help. The Germans realized by October 16th that they could no longer keep the land corridor with Walcheren Island open. They then flooded South Beveland.

Placing more emphasis on opening the approaches to Antwerp, on October 11, 21st Army Group gave that mission its top priority. First Canadian Army was relieved of the responsibility of securing Second British Army’s flank. Moreover, the latter was now to drive westward toward Breda to take the pressure off the Canadian right and attempt to trap the enemy south of the Maas River.

With more freedom of action, Simonds, temporarily in charge of the army while Crerar was on sick leave, directed British I Corps to the northwest while the 4th Canadian Armored Division moved to cut off the enemy facing the 2nd Division by taking Bergen Op Zoom. Meanwhile, the 49th, 1st Polish Armored, and newly assigned 104th U.S. Infantry Divisions would head northward for the Maas.

Nearing Breda on the 21st, the 49th Division was attacked by the German 245th Infantry Division. Although the attack was repulsed, it was apparent that the Germans would oppose what they saw as a threat to cross the Maas into Holland.

On the 23rd, the 6th Brigade, 2nd Division drove north to the high ground just south of Korteven, while the 5th Brigade closed the South Beveland isthmus. The following day, the division’s 4th Brigade marched west into Beveland and toward Walcheren. From the 27th to the 29th, the Canadians wrestled Bergen Op Zoom from the 6th Parachute Regiment. After more than three weeks of bitter combat, Fortress Scheldt had finally been fully invested.

By the end of September, the Germans south of the Scheldt had been confined to the “island” formed by the deepwater barrier of the Braakman inlet, the Leopold Canal, and the sea. The only land entry to the place was between the eastern end of the Leopold Canal and the Braakman on the Dutch-Belgian border. Known as Isabella, this fortress area held a garrison of the German 64th Infantry Division, 11,000 men strong, mostly veterans from the Eastern Front and Norway. Formed too late to take part in the Normandy battles, it was equipped with 500 machine guns, 200 antitank guns, and 70 pieces of artillery and supported by the five coastal batteries in the area as well as those on Walcheren Island. Well supplied with food and ammunition, it proved a formidable defensive force.

The Canadian 3rd Division was tasked with overcoming what came to be called the Breskens Pocket. The operation was dubbed Switchback. Simonds, blessed with a sufficient number of amphibious vehicles to cross the Scheldt, planned to attack with one infantry brigade where the Germans most expected an enemy assault across the Leopold Canal. A second brigade would soon follow the first. Two days later, after his opponent’s attention and reserves had been committed to fend off the first Canadian maneuver, a third brigade would cross the Braakman and land in the German rear.

Two battalions of the 7th Infantry Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division made the initial assault over the 90-foot-wide canal, which bordered dikes on both its banks. The German defenders were ensconced on the reverse bank of the canal dike, a difficult target for artillery. Flamethrowing Wasp armored fighting vehicles would attempt to clear enemy positions with blazing fuel.

Daylight on October 6 saw a sheet of flame delivered on the German side of the canal followed by the first boats carrying 3rd Division troops over the waterway. Many of the landing parties reached the opposite bank of the canal near Oosthoek unopposed. The defenders mounted several counterattacks. The 7th Brigade’s two small bridgeheads were unable to connect, so movement across the canal took place to the right at the village of Moershoofde.

Many of the attackers were confined to the waterlogged canal bank. German counterattacks were so numerous that the Canadians lost count. These assaults, made through narrow passages, were met by Canadian artillery fire on the far bank and many Allied fighter-bomber sorties, which exacted a high price from the Germans.

For five days the contest at the canal continued with the combatants separated by only yards. A Canadian attempt to send over an infantry company was defeated and the unit almost destroyed. For three more days the 7th Brigade struggled to enlarge its bridgehead until engineers bridged the canal on the night of the 13th, allowing tanks to cross. In the meantime, the 9th Brigade had landed to the northeast.

On October 9, the 9th Brigade, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division rushed from the city of Ghent to help the 7th Brigade. The reinforcements crossed the West Scheldt to the right of the German defenders, landing near the towns of Hoofdplaat and Braakman. Caught by surprise, the German division commander quickly sent in his reserves, followed by elements of the 70th Infantry Division from Walcheren. Aided by artillery fire from Flushing and Berskens, the Germans slowed the 9th Brigade advance. The 3rd Division’s last unit, 8th Brigade, was then slated to follow in the wake of the 9th, arriving on October 12. The main thrust of 3rd Division was now east to west instead of south to north.

Fighting along the area’s many dikes restricted the Canadian advance to single soldier fronts as the Germans fought with determination. The sky cleared several days after the battle began, allowing Allied airpower to drop 1,150 tons of bombs on the defenders.

On the 14th, south of the Braakman the 4th Canadian Armored Division attacked the Isabella area, meeting the 8th Brigade advancing from the north. By October 18, the 8th Brigade was eight miles from Oostburg at the center of Fortress Scheldt, while the 9th Brigade was two miles from Breskens on the coast. That same day the bloodied 7th Brigade was relieved from its bridgehead on the Leopold Canal by the British 157th Infantry Brigade. By the next day, the Germans had retreated to a shorter line from Breskens to Schoondijke, southwest through Oostburg and Sluis, and along the Sluis Canal to the Leopold Canal.

On October 21, the 9th Brigade stormed Berskens and the 20-foot-wide, 12-foot-deep antitank ditch surrounding it. Passing through the minefields protecting it, the attackers managed to capture the place by midnight, cutting off the Germans’ last link to Walcheren. Between the 22nd and 25th the fight for Schoondijke was fierce, but the town fell on the 25th. Oostburg was taken by the 8th Brigade, while 7th Brigade mopped up the west coast. On November 1, the last German resistance, centered on the village of Knocke, was eliminated, thus ending the operation to wipe out the Berskens Pocket.

As October 24 dawned, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, across the West Scheldt, advanced up the South Beveland Peninsula toward Walcheren Island 30 miles to the west. To bypass the obstacle created by the Beveland Canal on the path to Walcheren Island, Simonds decided to turn this area with a water-borne landing by the 156th Brigade, 52nd British Infantry Division on the southern shore of the peninsula west of the Beveland Canal. This mission was named Operation Vitality.

On the 26th, as the 2nd Division’s 4th Brigade overran the narrowest part of the South Beveland Peninsula, the 156th command landed on two beaches near Hoedekenskerke. During the day it had expanded its bridgehead in spite of a strong enemy counterattack from the north. The invaders then went on to occupy the town of Oudelande. By that afternoon, the Beveland Canal had been outflanked. The Canadians then split their forces, some heading to attack the Beveland Canal from the rear and the balance heading west.

On the 29th, it was certain that South Beveland would soon be in Allied hands. To the west lay the causeway, which carried a road, a rail line, and a bicycle path to Walcheren Island. Over the past few days the German had used these routes to escape the South Beveland Peninsula and find safety in Walcheren. The 2nd Division’s 5th Brigade was tasked with securing the causeway, and the division commander did not like the prospects. The 30-foot-wide objective rose a few feet above sodden mud flats and ran straight for 1,000 yards of barren ground across the gap from the mainland.

At midday on October 31, a company of the Black Watch stepped onto the causeway to determine if a crossing was feasible. The brigade’s Calgary Highlander Regiment prepared to cross to the island by boat at midnight. If the Black Watch was successful, the rest of the brigade would follow over the causeway.

As the Black Watch soldiers raced over the causeway they were met by a hail of enemy small arms and artillery fire. They soon discovered that a large crater in the road would prevent any tank support from following them.

While the Black Watch discovered the hole in the causeway, engineer officers discovered that even at high tide there would not be enough water to float boats across to Walcheren Island, and the mud flats would not support the weight of amphibious vehicles. In short, there appeared no other route to Walcheren except over the causeway.

On November 1, regiments of 5th Brigade braved heavy German fire to create a toehold on the western end of the causeway. But severe enemy shelling forced them back to the cratered middle part of the highway. At midnight the 5th Brigade’s Le Regiment de Maisonneuve pushed through the Black Watch and established a bridgehead on Walcheren. The 157th Infantry Brigade, 52nd British Infantry Division was then to exploit de Maisonneuve’s success.

Dawn broke on November 2 without any signs of 157th Brigade, but there were plenty of Germans, including a few tanks moving east and west of the regiment. Only the intervention of friendly fighter-bombers prevented the de Maisonneuves from being overrun.

Finally at 6 am, three companies from the Glasgow Highland Regiment, 157th Brigade ran across the causeway to join the Canadians on Walcheren. However, less than two hours later, under heavy enemy fire, the Canadian/ British force had to pull back to the road. It was only after a footpath over the mud flats south of the causeway at the Slooe Channel was discovered that enough troops were able to reach Walcheren by November 2 to secure a viable bridgehead on the island and link up with the friendly forces on the causeway.

The Canadians were now poised to capture Walcheren Island, held by the 70th German Infantry Division. Simonds put his scheme for its capture, code-named Infatuate, in motion. His plan called for the air bombardment of the island to breach its dikes to prevent the Germans from flooding the area to impede Allied movement. Using amphibious vehicles, the First Canadian Army could attack the enemy at any time and place of its choosing.

On November 1, the attack on Walcheren commenced. Landing craft were assembled at Breskens to join the 52nd British Infantry Division for an attack on Flushing. More than 300 artillery pieces were sited near Breskens to support the landings. Two seaborne assaults were to be carried out by the 4th Special Service Brigade, one at the town of Flushing on the southern tip of the island, the second at the town of Westkapelle on Walcheren’s west coast. Attacks from the South Beveland Peninsula were to coincide with the seaborne landings.

At 4:45 am, the four-mile crossing of the Scheldt from Breskens to Flushing began, followed shortly by artillery fire and air attacks, which smothered the city’s harbor in flames and smoke. By 6 am, the commandos landed, assaulting the German strongpoints on the beach. The German defenders came to life, pouring heavy fire into the attackers. The 155th Brigade, 52nd Division landed soon afterward.

Four hours after the first landings at Flushing, Royal Marines came ashore near Westkapelle. The Marines, along with 24 flails tanks and bulldozers from of the British 79th Armored Division, headed south for Flushing. Twenty-five Royal Navy warships provided close support. The landings succeeded because the German heavy artillery fire was directed at the ships instead of the landing craft carrying the assault troops and because the four German 150mm guns sited ran out of ammunition just as the infantry came ashore.

Around 3 pm the commandos, advancing through the sand hills, captured the battery near Domburg, but after fierce resistance halted short of the town. Another commando contingent took the artillery battery positioned three miles from Flushing the next day and reached the dike near Flushing on the 3rd.

Meanwhile, on the eastern side of the island the 156th and 157th Brigades fought a bitter battle against the Germans. The two units linked up at the causeway and started to clear the unflooded are east of Middleburg.

Back at Flushing, the 155th Brigade had a hard fight eliminating German forces from buildings and pillboxes. With the town finally in its hands, the 155th started for Middleburg. That town was now the concentration point for the main German defense of Walcheren. Surrounded by the city wall and flooded country, the Germans felt confident they could hold out indefinitely. However, that confidence proved to be misplaced. On October 6, a company of the Royal Scots Regiment floated aboard eight landing craft over flooded fields into the town behind the German defenses. Mistaking the amphibious vehicles for tanks, the town’s garrison surrendered.

Early on November 10, the last Germans on Walcheren Island gave up, and the approaches to Antwerp were clear of the enemy. After the war the Germans claimed that the flooding had made their situation impossible since the water prevented their gun positions from being resupplied, disrupted communications, and made troop movement difficult. Canadians and British amphibious capabilities set the course and tempo of the battle.

Throughout November more than 100 minesweepers labored to clear the 267 German mines in the West Scheldt. On the 28th, the first supply convoy to reach Antwerp, made up of 18 ships carrying 10,000 tons of stores, arrived. The cost to the First Canadian Army between October 1 and November 8 to allow the Allies unfettered control of the Scheldt was 703 officers and 12,170 enlisted men killed, wounded, or missing. During the same period the Germans lost 4,100 killed, 16,000 wounded, and 41,000 captured.

On the day the first Allied ships entered Antwerp harbor a ceremony was held to welcome the vessels. Representatives from Eisenhower’s headquarters, British 21st Army Group, the Royal Navy, and the Belgian government were present. Ironically, no one from First Canadian Army was invited to attend.

Arnold Blumberg is an attorney with the Maryland State government and resides with his wife in Baltimore County, Maryland.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments