By Gene J. Pfeffer

On August 17, 1942, the 97th Bomb Group began the opening attack of the U.S. Army Air Forces’ (USAAF) strategic bombing campaign against Germany. The mission was a strike by 12 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses against the railroad marshaling yards at Rouen, 40 miles into France from the English Channel.

The 12 bombers were escorted by four squadrons of Supermarine Spitfire fighters of the Royal Air Force (RAF). The first plane off the ground was flown by Major Paul Tibbets, who three years later would pilot the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay on its historic mission against Hiroshima. Sitting across from Tibbets was Colonel Frank Armstrong, the 97th commander. Armstrong was to serve as the model for Colonel Frank Savage, the lead character played by Gregory Peck in the famous World War II film Twelve O’Clock High!

On hand for the launch of the mission was Maj. Gen. Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, the commander of the USAAF Eighth Air Force, the primary organizational element that would carry the air war to Germany. Riding along in one of the strike aircraft was Brig. Gen. Ira Eaker, commander of the Eighth Bomber Command, the bomber component of the Eighth Air Force bomber and fighter forces. Eaker had spent most of his career as a fighter pilot not as a bomber disciple. However, he was convinced that daylight strategic bombing could inflict catastrophic damage on the fighting capability and military production capacity of an enemy.

This first raid was moderately successful, if pitifully small. About half the bombs fell within the target area; some rolling stock was destroyed, about one third of the track lines were damaged, and there were no bomber losses. After the raid Spaatz wrote to General Henry “Hap” Arnold, chief of the Army Air Forces, ”It is my opinion and conviction that the B-17 is suitable as to speed, armament, armor, and bomb load.” Eaker was more questioning. He wrote, “It is too early in our experiments in actual operations to say that it can definitely make deep penetrations without fighter escort and without excessive losses.” These were prophetic words.

The buildup of the aircraft and trained crews in southern England for Eighth had been slow. There were fewer than 100 B-17s in England at the time of this August 1942 mission. Far less than 100 aircraft were mission capable. Under increasing pressure from top U.S. political and military leaders to take the war to Germany, to do something with all the men and machines allocated to it, it was inevitable that Eighth Air Force missions would start as soon as possible.

The Failure of Unescorted Daylight Precision Bombing Raids

The form of warfare embodied in this first mission was the air strategy that Arnold, Spaatz, and Eaker had helped develop—unescorted daylight precision bombing of enemy industrial and military targets. In writing to Arnold before this first mission, Eaker said, “The theory that daylight bombardment is feasible is about to be tested when men’s lives are put at stake.”

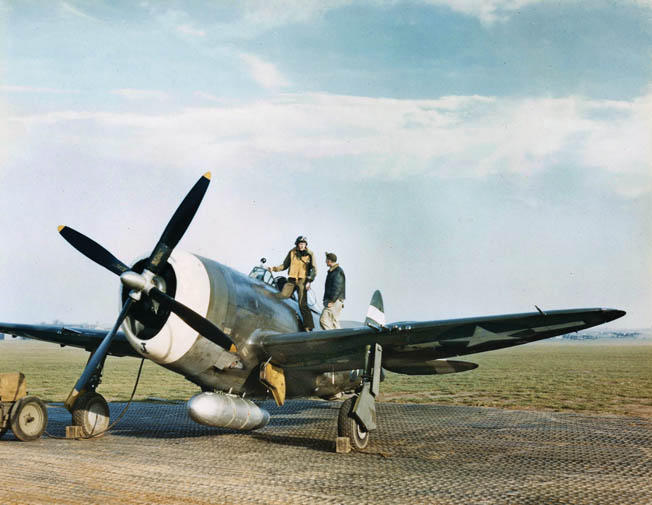

And tested it would be. As missions were pushed beyond the range of protecting British and American fighters, German fighters and air defense artillery destroyed American bombers at a great rate. By August 1943, a year after that initial raid, five times as many American bombers and airmen would be lost in attacks on two German industrial centers as had flown on that first mission. In the August 1943 dual raid on Regensburg and Schweinfurt, Colonel Curtis LeMay led 146 bombers against Regensburg while Brig. Gen. Robert Williams led 230 bombers against Schweinfurt. The bombers were escorted for parts of the missions by U.S. Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighters, but because of their limited range they could only go as far the western German border.

The German defenders had great advantages. The Luftwaffe fighter force was up in strength and could fly multiple sorties from its nearby bases. Twenty-four bombers of the 146 dispatched, carrying 240 crew members, were lost from the Regensburg force. From the 230 dispatched to Schweinfurt, 36 failed to return to bases in England. Combined, the two forces lost 60 of 376 bombers for a loss rate of 16 percent. But this number only told part of the story. In fact, an additional 20 percent of the attacking bombers were permanently lost to operations as a result of battle damage. In all, the raids cost the Eighth Air Force 40 percent of the bomber force dispatched from England.

Mission results were spotty. At Regensburg the aircraft plant was put completely out of action, but only briefly. At Schweinfurt, ball bearing production dropped by 38 percent, but it quickly recovered. These combined missions demonstrated clearly that for the Eighth Air Force the cost was too high. Both the aircrews and the senior leadership saw that such loss rates could not be sustained over the long haul.

Why were loss rates so high? Some historians have argued that the losses experienced on raids like Regensburg-Schweinfurt demonstrated clearly and unequivocally that the concept of unescorted daylight precision bombing was a failed strategy. Could Army Air Forces’ planners and leaders not have foreseen that German fighters would inflict unacceptable and unsustainable losses to the bombers unless they were escorted by protecting fighters? Why wasn’t an effective escort fighter available before late 1943? Were Army Air Forces leaders blinded to the flaws in the bombing strategy they had developed?

A close look at the historical facts demonstrates that it was not ignorance, hubris, or a misplaced commitment to their own thinking that led them to conclude that in 1942 and through the fall of 1943 the concept of unescorted daylight precision bombing was sound. Rather, it was a cold logic based on what was known and knowable at the time. To understand why this is so, it is necessary to understand the context of the times in which the planners and leaders worked.

The U.S. concept of strategic bombardment derived from the theories of airpower thinkers like Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell, who saw what even the primitive airpower of World War I could do. The resulting concepts were developed and refined at the Air Corps Tactical School (ACTS) at Maxwell Field in Alabama from 1926 until the beginning of the war in Europe. Although the ACTS taught these concepts to many airpower advocates, its doctrine lacked formal War Department approval. Accordingly, the spread of the doctrine was initially limited. The ACTS strategic bombing doctrine included the following components:

• The national objective of war is to break the enemy’s will to resist and force the enemy to submit to our will.

• The accomplishment of this goal requires offensive warfare.

• The special mission of air is the attack on the entire enemy national structure to dislocate its military, political, economic, and social activities.

• The disruption of the enemy’s industrial network is the real target because such a disruption might produce a collapse sufficient to induce surrender.

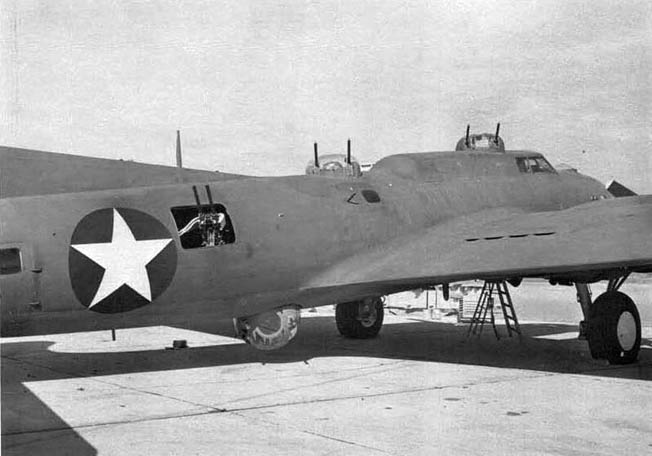

In 1935, the Army Air Corps took action to acquire a weapon system, although in small numbers, that enabled it to carry out its strategy—the four engine B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber. Its design was based on the technology then available, and it was initially sold as a weapon for coastal defense against naval threats. Fast for its time and well armed by contemporary standards, the B-17 was designed to fly in large numbers in a self-protecting formation for mutual defensive gunfire. Unaware of the British development of radar in 1935 as a means of detecting and tracking aircraft, the ACTS theorists believed, based on World War I and interwar experience, that bomber formations would reach their targets undetected or could fend off their attackers. They further expected to encounter the enemy only over the target, where the enemy would concentrate defenses rather than having to conduct a long-running battle to and from the objective.

Seeing the Need for a USAAF Escort Fighter

The state of prewar fighter and air defense technology supported these views. When strategic bombing theory was being developed at the ACTS, the leading edge fighter aircraft of the time had an externally braced single wing, a fixed landing gear, an open cockpit, short range, and light armament. These fighters could hardly keep up with a high-flying B-17 bomber in speed and took a long time to get to a bomber’s altitude. In fact, early versions of the Hawker Hurricane, the RAF’s first mono-winged fighter, were not fielded even in small numbers until mid-1938. To think in the early 1930s that the United States or any nation could within a few years develop a short-range, 380 mile-per-hour pursuit fighter with a closed cockpit, retractable landing gear, a cantilever wing, and internally mounted machine guns or cannons would have been extraordinary. But, that is exactly what happened.

Designing a rugged, fast, lightweight, highly maneuverable, and well-armed interceptor such as the Hurricane, the Spitfire, or the Messerschmitt Me-109 was one thing. Developing an effective long-range escort fighter was another matter. From 1935 to 1940, the design of an escort fighter that could fly fast enough to protect the bomber stream, had sufficient range to reach the target and return, and yet had good enough performance to fight successfully against enemy interceptors was judged by leading aeronautical engineers as not technically feasible. The extra fuel requirements alone seemed to make the escort heavier than the enemy’s interceptors, negatively impacting performance.

Even though the Army Air Corps, the predecessor to the USAAF, began a program in 1940 to explore ways to extend the range of fighters, the prevailing attitude of the Air Corps senior leadership was that the complete technology package for an effective, long-range, single-seat escort fighter was simply not available. Air Corps planners noted in 1941, “The technical improvements to the strategic bombardment airplane are or can be sufficient to overcome the pursuit airplane.” But they also noted, “It is unwise to neglect development of escort fighters designed to enable bombardment formations to fight through to the objective.”

As early as 1940, Lt. Col. Hal George, a bomber advocate and planner, was telling General Arnold that it appeared to him that bombers would definitely need fighter protection. But the aircraft envisioned by these planners was not a single-seat, high-performance fighter, but rather a convoy defender, a B-17 or similar large multi-engine aircraft modified to carry more armor, more guns, and more ammunition. Such a prototype, the YB-40, was to later prove in 1942 to be both costly and a complete failure in combat. In 1941, Arnold appointed a board of pursuit and matériel officers to recommend the future development of escort fighter aircraft. The board could not overcome the seeming disparity between the operational requirements for an effective escort fighter and the technology then available. The board made no recommendations.

Lessons of the Cross-Channel Air War

Through 1942, the attitude of both the Air Corps’ engineers and its combat leaders remained that bombers could be designed and operated to be effective against enemy air defenses and the technology for effective escort fighters was not at hand. The combat experience of the British supported this view. Eaker had been sent to England in the fall of 1941 for six weeks as a special air observer. As Eaker reported, the views of the Royal Air Force on bomber escort aircraft paralleled those of the Air Corps. The British had flown a number of daylight bombing missions against German targets on the French coast that were within the range of escorting British fighters. They had hoped to lure German fighters into an uneven fight. The tactic failed. The British bombing targets were just not of high enough importance to the Germans that they would engage the escort fighters.

The Germans would wait until the British bombers attempted deeper raids without escorts. They then took a heavy and unsustainable toll of British bombers. Prime Minister Winston Churchill asked why bombers could not be escorted farther over the Continent. The RAF Chief of the Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Charles Portal, wrote to Churchill that longer range escort fighters were not feasible. Portal said, “Increased range can only be provided at the expense of performance and maneuverability.” He added, “The long-range fighter, whether built specifically as such, or whether given increased range by fitting extra tanks, will be at a disadvantage compared to the short-range high-performance fighter.” Portal later wrote to Eaker, “The proper escort fighter will be a ship exactly like the bomber it is going to escort.”

Thus, the opinions held by a future ally already engaged for two years in an air war against Germany strongly supported the views of senior U.S. Army Air Corps officers regarding escort fighter development.

The Germans went so far as to field a fighter that had sufficient range to escort their Heinkel and Junkers medium bombers on strikes against England during the Battle of Britain. The Messerschmitt Me-109 had superior performance but limited range. The Luftwaffe responded to the escort fighter problem with the twin engine, longer range, and heavily armed Messerschmitt Me-110 Destroyer. It was fielded with the expectation that it would prove to be an ideal bomber escort and could effectively take on the RAF fighter aircraft. Spaatz and Eaker’s observations in England of the ongoing air war had quickly shown the disadvantage of the less maneuverable Me-110 against the RAF Hurricanes and Spitfires. It failed miserably as a bomber escort and would require escorts of its own during strikes on England. The Germans could only depend on their short-range Me-109 fighters to offer limited protection for their bombers due to the short time the fighters could loiter over Britain. By 1941, American, British, and German airmen were all convinced by the experience of the Battle of Britain and the follow-up RAF bomber raids against German targets that a plane capable of both long-range combat and successful dogfighting against high-performance pursuit fighters could not be built.

The problems of conducting an effective bombing campaign against well-defended targets haunted both the Germans during the Battle of Britain and the RAF in its 1940-1941 bombing campaign against German targets along the North Sea coast and in the Ruhr industrial area. Both air forces found that they experienced unsustainable losses during daylight raids, and both opted to move to nighttime bombing campaigns against industrial and politically significant cities.

Why then would American air leaders think they could do better? Both Spaatz and Eaker thought that they had other advantages that would discount the German and British experiences. First, the B-17 was a much more rugged aircraft than either the British or Germans had available to them. It could take a lot of punishment and keep going. Second, it had far better defensive armament—more and heavier guns than the few light-caliber weapons of the typical British and German medium bombers. Third, the United States would fly bigger and tighter defensive formations with far better mutual defensive firepower. U.S. leaders envisioned bomber missions of up to 1,000 aircraft flying in close defensive formations. Accordingly, based on their best professional judgment, U.S. airpower leaders were convinced of the correctness of their unescorted daylight precision bombing strategy.

But the old saying “You don’t know what you don’t know!” was particularly applicable to strategic bombing theory in general and to the need for long-range escort fighters in particular. The technology of air defense was evolving at such a high rate during the late 1930s and early 1940s that strategy and aircraft could hardly keep up with it. The development of radar both as a means of detecting bombers and for vectoring defensive fighters turned out to be a game changer. The ACTS strategists were unaware of early U.S. efforts in radar development that took place in great secrecy. An early prototype set was first demonstrated in 1938 but only to selected high officials. The bomber theorists knew little of Britain’s secret radar program and nothing of Britain’s integrated defense system that was so instrumental to victory in the Battle of Britain. The British developments that ushered in a new era of effective air defense were only revealed to Air Corps observers in August 1940 during the Battle of Britain itself.

Germany’s Air Defense Network

American air planners were not alone in their ignorance of evolving air defense technologies. Most Luftwaffe officers did not understand the role that radar could play in defense against bombers. While the Germans enjoyed a decided numerical advantage in the Battle of Britain, they ultimately lost that battle because they did not fully understand how radar and integrated air defense could multiply the effectiveness of the British fighter force. By 1939, the British had linked their Chain Home radar network to key command and control centers where the radar information was combined with reports of ground observers and intercepted German aircraft radio traffic.

The Germans learned fairly quickly how to fashion an integrated air defense system of their own. They had initially constructed an overlapping network of radar sites primarily for fighting against the nighttime raids of Britain’s Bomber Command. The densest parts of the network were in Germany, Holland, Belgium, and northern France. The day fighters that would oppose U.S. bombers would eventually benefit from this network when American bombing efforts began in earnest.

By 1943, the Germans also had developed an excellent radio intercept service. They were able to determine important operational factors such as preflight ground operations at bomber bases, weather forecasts for the bomber routes and target areas, the status of bomber navigational aids, and the routes of approach and return through direct intercept of voice transmissions or triangulation through radio direction finding of coded bomber aircraft radio traffic. Such transmission as “crossing enemy coast,” “30 minutes from target,” or “no clouds over the target” immeasurably aided German interceptor attacks on bomber formations.

In early 1943, the German view was that it was impossible for American bombers to carry out effective daylight raids. This was based on their own experience in the Battle of Britain. Should the USAAF try them, the Germans were convinced that a small German pursuit fighter force could ward off attacks with large losses to the bomber force. The Germans gave only slight consideration to the possibility the Allies could develop effective long-range escorts. By dismissing the possibility of having to do battle with high-performance escorts, the Germans eventually created a dangerous gap in defensive capabilities. Their failure to foresee where technology might go was every bit as costly to them as it was to the American planners.

Radar, electronic navigation, and signals intelligence continued to evolve rapidly as the war progressed, delivering capabilities that could not even be dreamed of in the late 1930s when strategic bombing doctrine became the centerpiece of Air Corps war fighting concepts. As the technology war evolved, newly developed German radar-controlled antiaircraft artillery took a great toll on Allied bombers both day and night. Maj. Gen. Haywood Hansel said after the war, “Our ignorance of radar development was probably a fortunate ignorance. Had this development been well known it is probable that the theorists would also have reasoned that, through the aid of radar, defensive forces would be massed against incoming bomber attacks in a degree that would have been too expensive for the offensive.” Had the strategists known of the developments in warning and tracking of bombing raids, the theories they propounded would have undoubtedly undergone major modification.

Extending the Range of Escort Fighters

By mid-1943, the thinking of USAAF leaders about the vulnerability of the bomber force and the promise of new technologies began to evolve. In spite of being escorted part of the way by P-47s, the massive air attrition battles of 1943 like the Regensburg-Schweinfurt mission badly eroded both bomber aircraft numbers and aircrew strength. Arnold was beginning to think that the bomber attrition rate was too high to be sustained even with the enormous bomber production and aircrew training going on in the United States. In June 1943, Arnold wrote Maj. Gen. Barney Giles on the air staff that by January 1944 he wanted an effective long-range escort fighter in Europe. He wrote again in September 1943, “Operations over Germany conducted during the last several weeks indicate definitely that we must provide long-range fighters to accompany daylight bombardment missions.” But Arnold and the USAAF continued to apply pressure to Germany with what they had while stepping up efforts to solve the bomber attrition problem.

As bomber units rebuilt in late 1943, tactics were changed. Additional escorts were added to cover as much of the outward and inward legs of the missions as possible, but the bombers were still without fighter coverage when they outran the range of P-47s and Lockheed P-38 Lightnings on raids deep into Germany. The ever increasing effectiveness of the German defenses, both air defense artillery and fighter interceptors, continued to prove devastating. On a followup mission to Schweinfurt in October 1943, outright losses were 26 percent of the attacking force.

But the technology that was unforeseen in the late 1930s and early 1940s was beginning to come together to fill the need for a high-performance, long-range escort fighter. It took a very fortuitous confluence of events for it to happen. One development was the auxiliary gas tank carried under the wings or fuselage of Allied fighters. The USAAF pursuit board had in 1940 and 1942 considered a range extension program for fighters including expendable external auxiliary fuel tanks. But it did so as a means of extending fighter endurance in support of its primary mission—defensive actions against the hostile bomber. It never connected the single-engine pursuit fighter and drop tanks with the bomber protection problem.

In May 1941, Lt. Col. Bob Olds was given the task of organizing the ferrying of Lend-Lease planes to England. He was an advocate of adding range to all fighter aircraft to increase their ferrying capability. As part of that effort, Lockheed and Republic were asked to increase the range of the P-38 and P-47 fighters they were producing. The modifications of these aircraft, essential for any escort role, were pushed forward to increase their ferrying range, not their combat range. Thus, by chance the P-38s and P-47s delivered to the Eighth Air Force in 1942 (P-38) and 1943 (P-47) were given the capability to extend their combat ranges. With the addition of the tanks, these fighters could escort the bombers farther but still not far enough. They could not go all the way with the bombers on deep strikes into Germany. German fighters would learn to wait and attack the bombers after the escorts had to turn for home.

The P-51: A Major Breakthrough in Escort Fighter Design

The key development that enabled effective bomber defense was the evolution of fighter design. In 1940, North American Aviation was asked to propose a fighter aircraft in response to a British requirement for a reconnaissance and ground attack fighter bomber. The chief designer at North American was Edgar Schmued. The German-born Schmued had formerly worked for Willie Messerschmitt, the designer of the Me-109 fighter, before immigrating to the United States. It was his intention to build an exceptionally clean aircraft showing superior aerodynamic characteristics. When in early 1940 the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics first released information on the new laminar flow wing, Schmued incorporated this new wing concept into the design of the fighter. The new wing promised about 20 percent less drag than older designs. That equated to better performance and longer range. Reports from England, where the prototype was flight tested, were favorable with respect to the low-level performance of the new fighter, an early variant of the famed P-51 Mustang.

The original Mustang as designed for the British had an underpowered Allison engine. It did not perform well at altitudes above 15,000 feet. It was pure serendipity that a pilot who flew one of the early British versions suggested its performance could be significantly improved by replacing the Allison engine with the same Rolls-Royce Merlin engine that powered the RAF Spitfire. That idea was the stroke of genius that made the Mustang a great high-altitude fighter. It matched or bettered the performance of any German fighter except the Messerschmitt Me-262 jet fighter that entered operations too late to affect the outcome of the air war. But even with external drop tanks, the P-51 did not have the range to escort bombers on their deepest penetrations into German territory. It took further design work to come up with a fix.

In the summer of 1943, North American was told to add another 200 gallons of gas storage to the P-51 design. The head of the company said that it was impossible to accomplish because the landing gear would not hold the additional weight. He was told to try it anyway. He did. Schmued was able to modify the design to provide for an 85-gallon fuselage tank to the rear of the armor plate behind the pilot. With further design modifications, the P-51 with the internal tank plus 108-gallon drop tanks could fly to Poland, a round-trip of 1,700 miles, at speeds approaching 440 miles per hour and at altitudes up to 40,000 feet. It was now the fuel load of the bombers that limited the range of Eighth Air Force strikes.

“Big Week”

By early 1944, the Eighth Air Force was being reinvigorated. In January 1944, Ira Eaker was relieved of command of bomber forces in England and given command of all Allied air forces in the Mediterranean. Maj. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle replaced Eaker. Several things changed. Finally, there were enough bombers available to put together formations of hundreds of bombers. There were enough bombers that formations now were able to provide optimum defensive firepower. Additional guns were added to the front of the B-17s to deter the deadly frontal attacks of German fighters. By February 1944, the U.S. bombers forces were able to mount 1,000-bomber daylight missions against the German heartland.

Just as important, beginning in early 1944 the Army Air Forces in Europe and the Mediterranean began to receive large numbers of P-51 fighters with the range necessary to escort bombers deep into enemy territory. Other fighters such as the P-38 and P-47 also benefited from the great range provided by external fuel tanks.

The pipeline that had only slowly increased the Eighth’s combat power in 1943 overflowed with new aircraft and crews in 1944. The Battle of the Atlantic against German submarines had by now been won, and U.S. production was booming. The number of fully operational heavy bombers in Britain rose from 451 to 1,655 despite increased operational losses. The Eighth’s fighter strength increased from 274 to 882, mainly P-47s and P-51s. The Eighth also acquired bombing radar that enabled many more bad weather missions even though bombing was less accurate than with the Norden bombsight.

Spaatz also incorporated a strategy of offensive counter air, unleashing his fighters to go after German fighters on the ground. He told Doolittle that his primary mission was the destruction of the Luftwaffe. By choosing to attack the Luftwaffe rather than solely defend against it, he found the way to defeat the German fighter force through attrition. By early 1944, the USAAF had the means as well as the method. Fighter sweeps with long-range fighters disrupted all German air activity from pilot training to going after U.S. bombers.

All of these changes culminated in Operation Argument. On February 20, 1944, the Eighth Air Force and Fifteenth Air Force (based in Italy) began a systematic and coordinated attack on the German fighter aircraft industry and fighter airfields. On this date, for the first time, the Eighth sent out more than 1,000 heavy bombers.

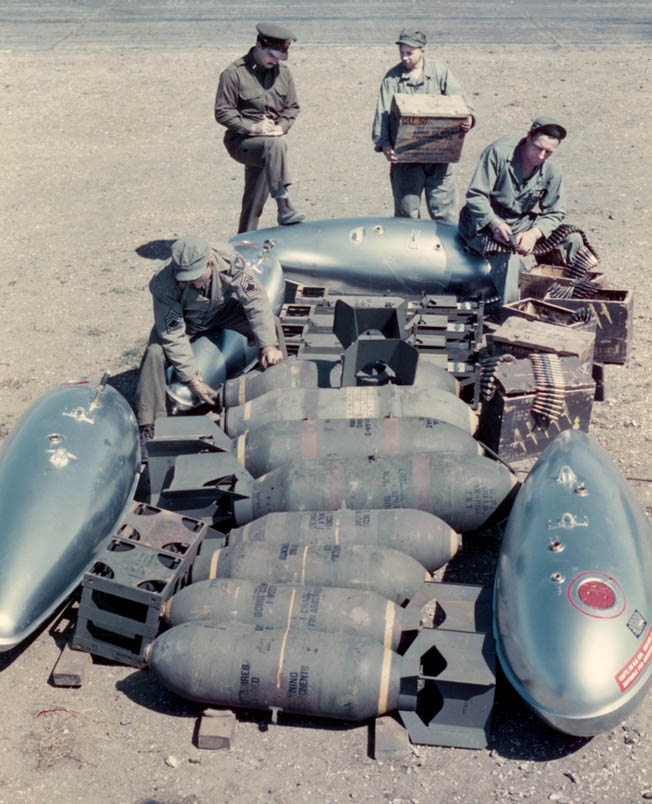

The weeklong operation became known as “Big Week.” This operation, planned since early November 1943, called for a series of combined attacks by the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces against the highest priority objectives. Sixteen combat wings of heavy bombers (more than 1,000 bombers), all 17 USAAF fighter groups (835 fighter planes), and 16 RAF squadrons (to assist in short-range penetration and withdrawal escort) began their takeoff runs, assembled, turned to the east, and headed for 12 major assembly and component plants that constituted the heart of Hitler’s fighter production. The mere fact that the Eighth intended to hit 12 German targets in one mission spoke to the newfound confidence of its commanders and their determination to strike hard. Only 21 heavy bombers of the 889 that reached their targets (2.4 percent) failed to return to base.

Over the following days, both the Eighth and Fifteenth put up large missions against German targets in Denmark, Austria, and Germany. Over the course of Big Week, the Americans had proved that they could fly into the worst the Luftwaffe could muster, as long as they had fighter escort, and could do so with an overall loss rate of less than 5 percent. In all, the combination of U.S. strategic bomber and supporting fighter forces in Europe lost approximately 266 heavy bombers, 2,600 aircrew members (killed, wounded, or captured), and 28 fighters. In all of February, the Eighth wrote off 299 bombers, one fifth of its force, whereas the Luftwaffe wrote off more than one third of its single-engine fighters and lost almost 18 percent of its fighter pilots.

Big Week was big not only due to the physical damage inflicted on the German fighter industry and frontline fighter strength, but also to the psychological effect it had on the Army Air Forces. In one week Doolittle dropped almost as much bomb tonnage as the Eighth had dropped in its entire first year. In combat the AAF had shown that precision bombing in daylight not only performed as claimed, but also at no greater cost than the supposedly safer and less accurate night area bombing. What is more, the American fighter escorts destroyed many enemy fighters. German sources supported the conclusion that the Germans lost between 225 and 275 aircraft during Argument, primarily to U.S. long-range escort fighters. In their own minds, General Spaatz and other high-ranking American air officers had validated their belief in their basic strategy of precision daylight bombing.

The Decline of the Luftwaffe

Although the Luftwaffe fighter force actually increased its bomber kills in March and April 1944, Big Week was the beginning of the end for the German daylight fighter. The United States Strategic Air Forces’ (USSTAF) assistant director of intelligence said three weeks later, “I consider the result of the week’s attack to be the funeral of the German Fighter Force.” He added that USSTAF now realized that it could bomb any target in Germany at will. A key contributor to the eventual success of the strategic bombing campaign was the development of the long-range escort fighter, primarily the P-51.

In 1937, the German Luftwaffe had the best interceptor fighter in the world in the Messerschmitt Me-109. After the war began, German fighter development faltered. The Luftwaffe’s primary mission was support of the German Army. Air-to-air fighting had only been considered to the extent it supported gaining air superiority for the land battle. Also, the meddling of Hitler, who insisted it be developed as a bomber, delayed the production of the Me-262 jet fighter to a time so late in the air war that the Allies had already achieved overwhelming air superiority.

By the time the P-51s entered the fight in large numbers, the Luftwaffe pilot force had been greatly reduced in effectiveness. U.S. commanders knew of the sorry state of German pilot training and combat experience from decrypted radio messages. The AAF intentionally put up large bomber formations to lure the Germans into air-to-air combat with U.S. escort fighters. By the time of the D-Day landings in France in 1944, the Germans could mount only a few hundred sorties to oppose the Allied landings. Most of the German fighters had been drawn back into Germany to oppose the devastating Allied bomber raids.

The 273,841 Sorties of the Eighth Air Force

For the bomber offensive as a whole, the Eighth Air Force lost 4,182 aircraft from a total of 273,841 sorties, a rate of 1.5 percent. RAF Bomber Command, whose leadership shifted to night bombing to reduce losses, had a higher loss rate of 2.5 percent over the course of the war. The 250,000 aircrew members who flew bomber missions in the Eighth Air Force during the course of the war sustained 58,000 casualties—18,000 killed, 6,500 wounded, and 33,500 missing. The RAF Bomber Command lost 49,000 killed.

It is easy in hindsight to criticize the conduct of the strategic bombing campaign and the development of bombers and escort fighters. However, the postwar occupation of Germany found that its economy and its national infrastructure had been devastated to the point that they barely functioned. The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey stated, “Allied airpower was decisive in the war in Western Europe.” This was confirmed by German Armaments Minister Albert Speer after the war when he said that bombing created a “third Front” and that “without this great drain on our manpower, logistics, and weapons, we might have knocked Russia out of the war before your invasion of France.”

While the P-51 provided the answer to the need for a highly effective, long-range escort fighter in Europe, it was to prove less successful in the Pacific, where the long-range B-29s were used against the Japanese homeland, and even the improved P-51 did not have the necessary range. Many GIs died to secure islands close to the Japanese homeland as bases for the P-51s to escort the bombers.

After more than 70 years, it is easy to overlook the context of the times when assessing bomber and fighter strategies of World War II. The difficulties the planners encountered at the time far exceeded what can be readily seen. The air power planners of the 1930s could not know with any certainty that Hitler would start a war in Europe, that the Japanese would attack Pearl Harbor, that the laminar wing would be invented, that radar would enable integrated air defense, that outnumbered Britain would survive a German bombing campaign, and that the German people and industry could endure the destruction of their major cities.

It is all too easy to conclude that solutions like the long-range, high-performance escort fighter were obvious. However, when viewed in context, it is reasonable to conclude that Allied air leaders did well given the complexity of the times and the rapid pace of technological evolution.

Author Gene Pfeffer resides in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He served 30 years in the U.S. Air Force working in the areas of weather, space operations, and research and development, retiring with the rank of colonel as Vice Commander of the Air Force Weather Service. After retiring from the Air Force, he worked in the aerospace industry.

My reading indicates that the lack of a fighter with sufficient range was down to two things:

1. The failure of USAAF to thoroughly develop drop tank technology early in the war. Late war P-47’s equipped with a panoply of drop tanks were fully capable of escort all the way to Berlin and back. Even by the time of Schwienfurt, the 47 equipped with limited drop tankage woukd have had a radius of action 25 miles past Schwienfurt had the Eighth fully committed to implementing existing drop tanks on its available fighters. The question then becomes, why didn’t they? That also doesn’t address the existence of a fighter in US inventory that in fact did have the needed range, the P-38 Lightning. Additionally, in 1939 Arnold himself had ordered that experiments with drop tanks for pursuit aircraft be terminated. Why?

2. The predominance of the politically connected so-called “bomber mafia” who maintained its advocates in high level staff positions during the late 1930’s and early 1940’s was philosophically committed to daylight, unescorted, precision bombing. With limited funds available in the late 30’s it made sure to kill projects and limit officers that may have threatened its funding priorities. Indeed, part of the reason Claire Chennault, being a vocal pursuit development advocate, retired from the USAAC was over squabbles with higher level staff officers in the organization committed to the daylight unescorted bomber concept.

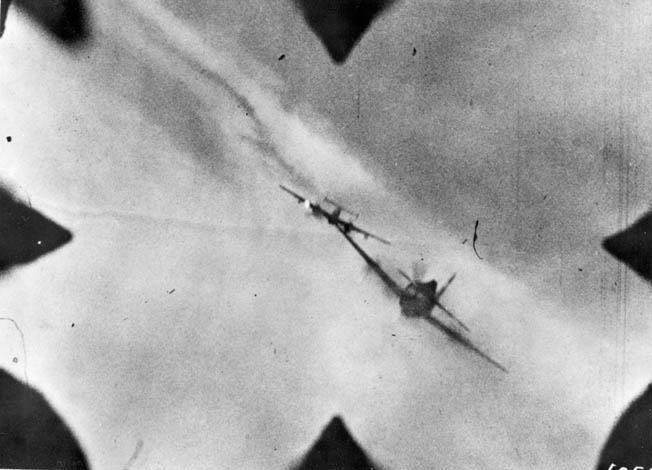

You know me – I hate to nitpick, but regarding the article’s photo from the gun camera of the P-47. It looks like the B-17 was fitted with the tail of a B-24. Just wondering if the bomber in the photo was misidentified.

A couple of points in response. Many of the “bomber mafia” were originally pursuit (fighter) guys like Eaker and Hansell. While planners intially thought or hoped unescorted missions were sustainable, it became obvious in late 43 that it wasn’t the case. If the P-38 was such a great long range escort in the European fighter why were its mission capable rates and combat successes so low. The P-38 had design problems in the very cold air high over Germany in the winter. It didn’t face those difficulties in the Med or Pacific. It was very successful in those theaters where combat was lower and warmer. The 8th got rid of most of its P-38s as soon as other options became available. I think it’s high improbable even impossible that if a long-range escort (supposedly the P-38) were available in the midst of the high bomber losses in late 43 that the 8th leadership wouldn’thave begged for more. They didn’t. As regards drop tanks on the P-47, the P-47s escorted early in missions because even with drop tanks their range out of England was limited to the German border for most of the air war. In 1944 even with two 108 gal drop tanks the P-47 couldn’t go further than Frankfurt, well short of Berlin. Let the debate continue.

Regarding the photo that was commented on, it’s the gun camera of one P-47 showing another P-47 shooting at an Me-110 (the split tailed aircraft).

Quote from the article, “The German-born Schmued had formerly worked for Willie Messerschmitt, the designer of the Me-109 fighter, before immigrating to the United States”.

It’s an oft quoted “fact” that Schmeud once worked for Messerschmitt, but the real fact is he never did.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Schmued

My uncle Jack flew the Mustang. He received the Distingiushed flying cross twice. Once for taking on 100 enemy combatants and downing 5 ( ace of the day) and another for successfully (multiple times) crossing some heavily fortified line you had to cross to enter German air space. Retired from flying……….age 23.