By Don Hollway

A week after the first shots of the War Between the States at Fort Sumter in April 1861, the future of warfare came to Appalachia. Plowmen in the remote Allegheny Mountains heard a voice calling, “What state is this?” and, seeing no one about, replied toward the nearest woods: “Virginia.”The voice answered, “Thank you,” and the farmers were startled by a stream of sand pouring, unbelievably, from the sky. Looking up they saw, hanging in space above them, a gargantuan cloth sphere. Professor Thaddeus S.C. Lowe had merely dumped ballast from his balloon, but remembered, “A yell of horror arose from them, and if fleetness of foot is any indication of fright, then they must have been terribly frightened.”

If being observed from the skies was an alien experience to most people of the 1860s, navigating the skies was even more so. Lowe had lifted off from Ohio, hoping to reach Washington, D.C., as proof that a hydrogen balloon could make a trans-Atlantic passage, but contrary high-altitude winds carried his Enterprise more south than east: “I finally landed in South Carolina, a short distance from the line of North Carolina.”

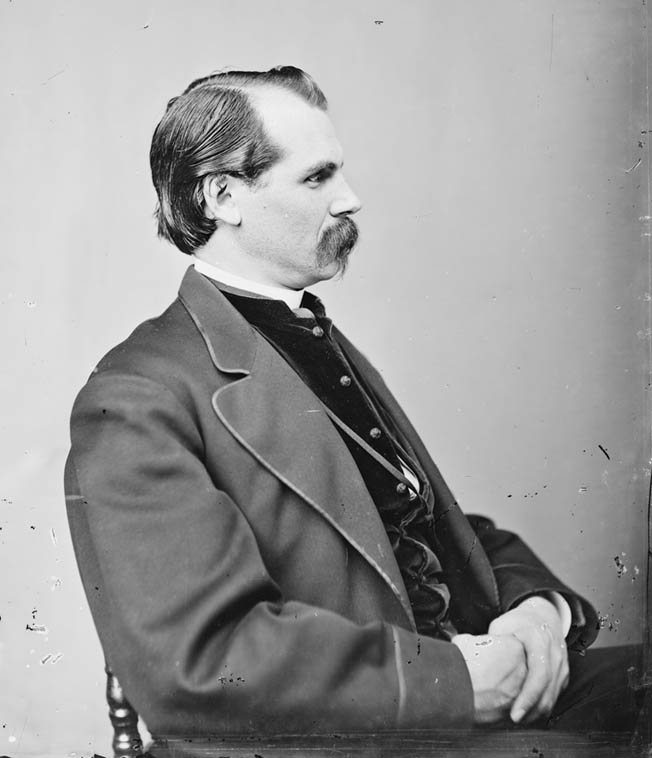

Upon touchdown he was disconcerted to find himself surrounded by ardent new Confederates. Virginia having seceded just two days earlier, he was very likely the first captive taken in the American Civil War. Lowe had long since established himself as one of the world’s foremost aerialists. His title was born of showmanship rather than any official scientific degree, but Lowe never balked at self-promotion. In September 1860, only a gasbag tear had prevented his 103-foot-diameter balloon, Great Western, from taking off with an 11.5-ton load, including an eight-man gondola and lifeboat, across the Atlantic Ocean. His scientific credentials were enough to convince the Southern authorities that he was merely a stray Yankee. Rather than imprisoning Lowe, they politely put him and his floating contraption aboard a northbound train.

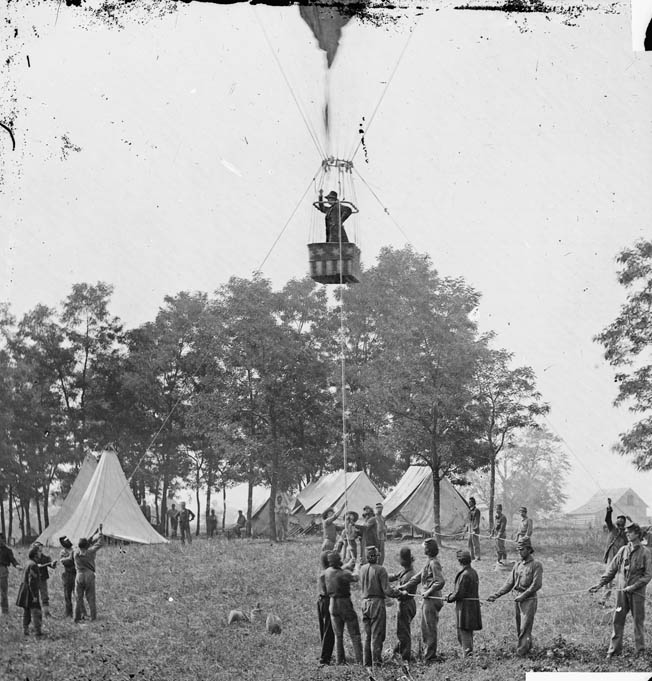

Though Lowe had not reached Washington, word of his exploit had. The U.S. Army had little interest in using balloons over the Atlantic but much interest in using them over the Confederacy. On June 16, 1861, at the invitation of the War Department, he ascended in Enterprise 500 feet above the capital, telegraphing U.S. President Abraham Lincoln in the White House: “This point of observation commands an area nearly 50 miles in diameter,” he wrote. “The city with its girdle of encampments presents a superb scene. I have pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station.”

From above Maryland, observers could overlook Confederate outposts halfway to Manassas Junction, Virginia, 25 miles away. Control of this new “high ground” led, perhaps, to overconfidence. A month later Lowe packed his balloon and followed the Army of the Potomac toward the Battle of First Bull Run, only to run into a panicked throng of Federal troops, civilians, and day-tripping politicians fleeing the other way. When he took to the air to look out for any enemy pursuit, friendly forces vented their frustration on him. “Within a mile of the earth our troops commenced firing at the balloon, supposing it to belong to the rebels,” Lowe wrote. “I descended near enough to hear the whistling of the bullets and the shouts of the soldiers to ‘show my colors.’”

Lowe had not thought to bring a flag. “Knowing that if I attempted to effect a landing there my balloon—and very likely myself—would be riddled,” Lowe wrote. “I concluded to sail on and to risk descending outside of our lines.” He landed hard, punctured his gasbag, twisted his ankle, and spent a long night alone in enemy territory. Legend has it that his wife, Leontine, rode through the lines in a buckboard to retrieve him and his balloon. “A detailed account of my escape would be interesting, but it is sufficient to say that I was kindly assisted in returning by the Thirty-first Regiment New York Volunteers, and brought back the balloon, though somewhat damaged,” Lowe wrote.

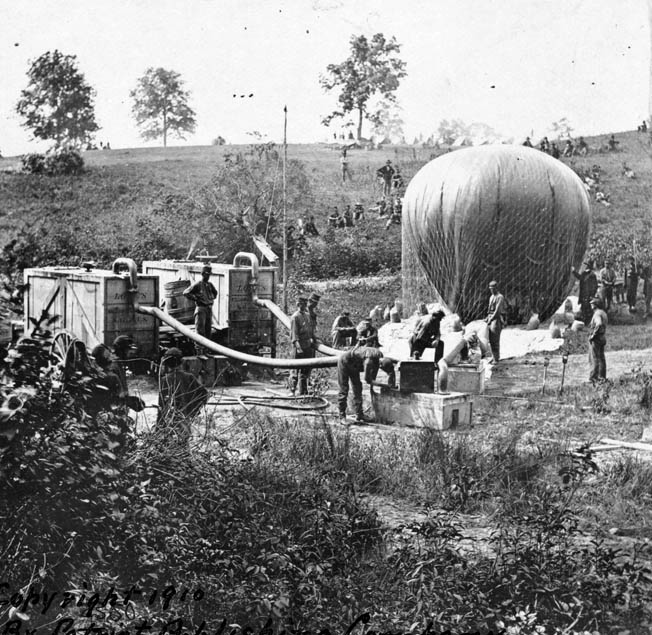

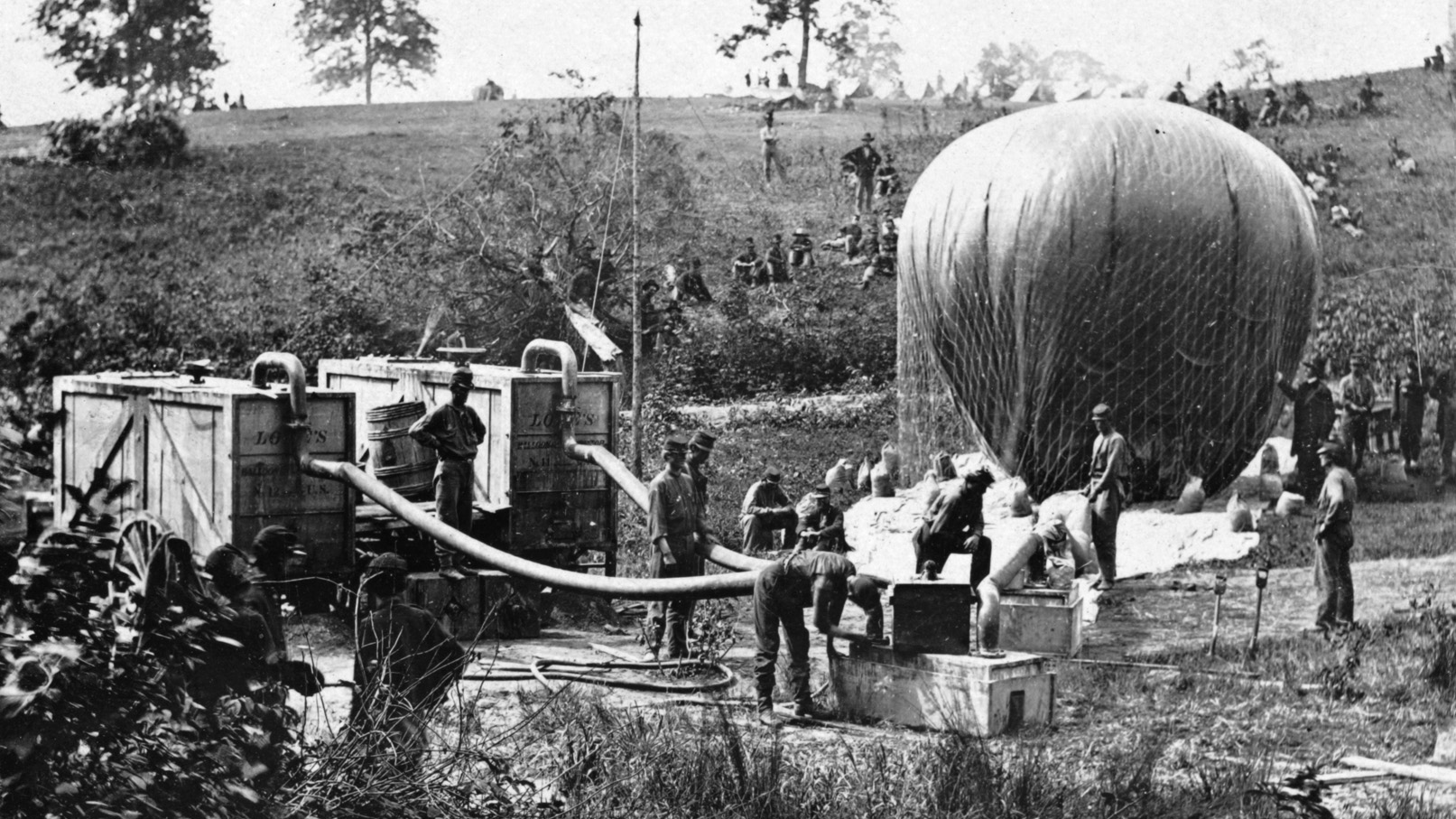

The Army offered to pay for a new gasbag. “From this time until the 28th of August was consumed in the construction of the first substantial war balloon ever built,” Lowe wrote. “The main obstacle to the successful use of balloons still had to be overcome, namely, a portable apparatus for generating the gas in the field. I had already devised a plan for this purpose.” His generators would use dilute sulfuric acid on iron filings to give off pure hydrogen.

When the Confederates pressed to within two miles of the Potomac, Lowe and his balloon rose in front of them. “The enemy opened their batteries on the balloon and several shots passed by it and struck the ground beyond,” he wrote. “These shots were the nearest to the U.S. capital that had been fired by the enemy, or have yet been, during the war.” He paid them back in kind, pinpointing Confederate positions from more than three miles away and using his telegraph to call down Federal artillery on them. It was the first aerially directed fire support in history.

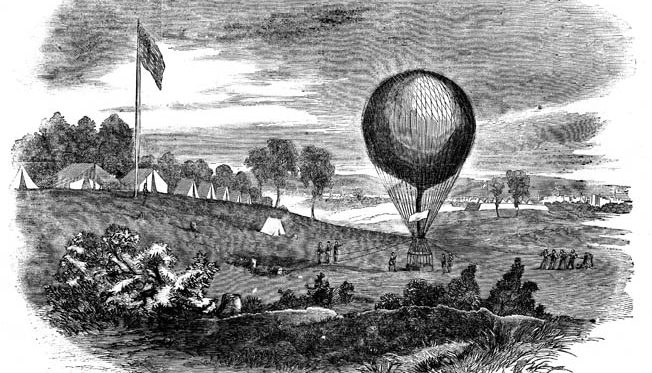

Lincoln ordered the formation of the Union Army Balloon Corps, with Lowe as chief aeronaut, but the government neglected to fund his portable hydrogen generators. He had to inflate his new balloon, the Union, with coal gas from Washington, D.C., city lines—32,000 cubic feet of it—and tow it to the war zone. No sooner was it tied down in Virginia than a storm blew up. Mooring lines tore. The unmanned balloon whisked away to come down 100 miles away on the Delaware coast, but Lowe’s military-grade gasbag held.

In early November the professor pioneered another military first: the aircraft carrier. He had the coal barge USS George Washington Parke Custis fitted with a “flight deck” and his new gas generator, towed out onto the Potomac by the steamer USS Coeur de Lion with his 20,000-cubic-foot-balloon, Washington. “I proceeded to make observations,” he wrote, “and saw the rebels constructing new batteries at Freestone Point.” These guns commanded the river from atop a cliff 90 feet above the water, invisible from the Maryland side except from the air; targeted by Federal warships, the site was soon abandoned.

By the beginning of 1862, the Union Army Balloon Corps had five balloons in operation, including the 15,000-cubic-foot Eagle serving as eyes for the gunboat siege of Island No. 10 in the Mississippi at New Madrid, Missouri. “During the bombardment,” Lowe wrote, “an officer of the Navy ascended and discovered that our shot and shell went beyond the enemy, and by altering the range our forces were soon able to compel the enemy to evacuate.” The loss of the strategic river bend that April directly contributed to the South’s eventual loss of the entire Mississippi—the cutting in two of the Confederacy.

The Southerners, however, were becoming wise to being watched from above. They had convinced Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan that they held overwhelming numbers until balloonists reported that they had in fact evacuated. Cautiously advancing Union troops found enemy artillery positions mounting “Quaker guns,” which were logs painted black to fool observers.

Chastened by the deception, McClellan took the Balloon Corps along on his invasion of the Virginia Peninsula, where Union scouts reported another 100,000 Southerners blocking the way to Richmond. From 1,000 feet above the peninsula it was plain to Lowe that the reports had vastly overestimated enemy forces, but again McClellan played it safe, settling down to besiege Yorktown. The professor watched the Confederates strengthening their positions, to their mutual displeasure. “Almost daily whenever the balloon ascended the enemy opened upon it with their heavy siege guns or rifled field pieces,” he wrote, “until it had attained an altitude to be out of reach, and repeated this fire when the balloon descended, until it was concealed by the woods.” Southern ire was partly enflamed by the huge portrait of the Balloon Corps’ patron, McClellan, emblazoned on Intrepid’s 50-foot envelope, looking down on them. (The balloon bag is referred to as the envelope.) They went so far as to build their own primitive hot air balloon, which Captain John R. Bryan flew over Yorktown, but clumsy handling and friendly fire made his a risky job; the Confederate balloon ultimately crashed and was destroyed. On Saturday, May 3, Lowe lifted off from McClellan’s own headquarters: “No sooner had the balloon risen above the tops of the trees than the enemy opened all of their batteries commanding it, and the whole atmosphere was literally filled with bursting shell and shot, one, passing through the cordage that connects the car with the balloon, struck near to the place where McClellan stood.” Upon landing Lowe was duly informed, “The general says the balloon must not ascend from the place it now is any more.”

The barrage continued all day. “The last shell fired after dusk came into [Brig. Gen. Samuel P.] Heintzelman’s camp and completely destroyed his telegraph tent and instruments, the operator having just gone out to deliver a dispatch,” Lowe wrote. “The General and I were sitting together discussing the probable reasons for the enemy’s unusual effort to destroy the balloon when we were both covered with earth thrown up by the twelve inch shell. Fortunately it did not explode.”

Cause for enemy concentration on the balloon soon became apparent. Lowe was awakened that night by reports that the barrage had abated and fires were burning in the city. “I ascended at a point near Yorktown and discovered that the enemy had left, and at 6 o’clock a portion of them were visible about two miles from Yorktown on the road to Williamsburg,” he wrote. “It is fair to presume that the first reliable information given of the evacuation of Yorktown was that transmitted from the balloon to General McClellan.”

Lowe and his unit joined the Union pursuit. By the end of May, the Confederates in Richmond could see balloons marking a near quarter-circle northeast of the city, hampering their efforts to counterattack. “The balloons of the enemy forced upon us constant troublesome precautions in efforts to conceal our marches,” recalled Confederate Chief of Ordnance Lt. Col. Edward Porter Alexander. The Southerners fashioned a new balloon, the Gazelle, from swatches of silk dress fabric—not, as is often reported, from dresses donated by Southern ladies—and Alexander would fly it in the ensuing assault.

“The enemy commenced to concentrate their forces in front of Fair Oaks,” Lowe wrote, “moving on roads entirely out of sight of our pickets, and concealing themselves as much as possible in and behind woods, where none of their movements could be seen, except from the balloon.”

A French observer with the Union Army wrote, “There was some doubt whether the enemy were making a real attack, or whether it was merely a feint; but this doubt was soon removed by reports from the aeronauts, who could see heavy columns of the enemy moving in that direction.”

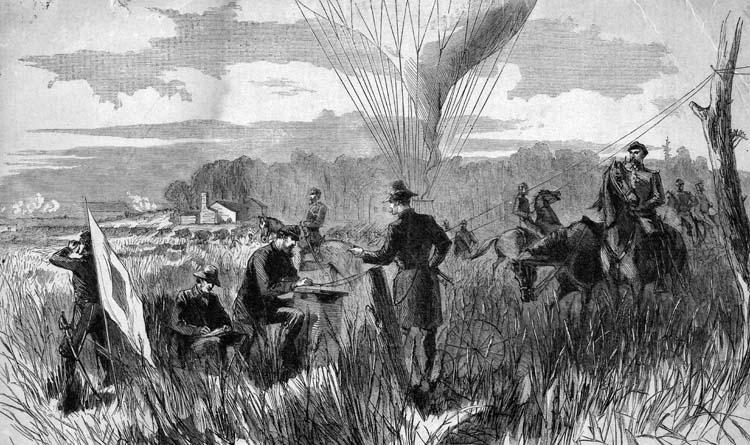

“I knew exactly where to look for their line of march,” Lowe wrote, “and soon discovered one, then two, and then three columns of troops with artillery and ammunition wagons moving toward the position occupied by Heintzelman’s command.” Isolated across the rain-swollen Chickahominy River at the crossroads of Seven Pines, Heintzelman’s III Corps could be reached only via one rickety, flood-damaged bridge. “All this information was conveyed to the commanding general,” Lowe recalled, “who, on hearing my report that the force at both ends of the bridge was too slim to finish it that morning, immediately sent more men to work on it.”

The Southerners would not wait. “I used the balloon Washington at Mechanicsville for observations, until the Confederate army was within four or five miles of our lines,” wrote Lowe, who “telegraphed my assistants to inflate the large balloon, Intrepid…. I then took a six-mile ride on horseback to my camp on Gaines Mill.” On his arrival, however, he found Intrepid still only partially filled. “It was then that I was put to my wits’ end as to how I could best save an hour’s time, which was the most important and precious hour of all my experience in the army. As I saw the two armies coming nearer and nearer together, there was no time to be lost. It flashed through my mind that if I could only get the gas that was in the smaller balloon, Constitution, into the Intrepid, which was then half filled, I would save an hour’s time, and to us that hour’s time would be worth a million dollars a minute…. In the course of five or six minutes connection was made between both balloons and the gas in the Constitution was transferred into the Intrepid…. Then with the telegraph cable and instruments, I ascended to the height desired and remained there almost constantly during the battle, keeping the wires hot with information.”

The New York Herald reported, “During the whole of the battle of this morning, Professor Lowe’s balloon was overlooking the terrific scene from an altitude of about two thousand feet…. This is believed to be the first time in which a balloon reconnaissance has been successfully made during a battle, and certainly the first time in which a telegraph station has been established in the air to report the movements of the enemy and the progress of a battle. The advantage to General McClellan must have been immense.”

McClellan ordered Brig. Gen. Edwin C. Sumner’s II Corps over the bridge to halt the Confederate attack. Adolphus W. Greeley, then an 18-year-old soldier in Sumner’s command but ultimately a major general and Chief Signal Officer of the Army, would write in Harper’s Weekly, “It may be safely claimed that the Union Army was saved from destruction at the Battle of Fair Oaks … by the frequent and accurate reports of Lowe.”

Having barely withstood the assault, McClellan required three weeks to come up with a riposte, meanwhile relying on his balloonists to stand guard. To keep the initiative, General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, made targeting them a top priority. On the morning of June 26, Lowe’s assistant James Allen (himself an accomplished prewar aeronaut) was floating in the Union near Mechanicsburg when he spotted a Confederate detachment about to surround his own base camp. He called to be pulled down, but when shots began flying past his basket he jumped out and slid down one of the mooring lines. He, his crew, and their balloon just escaped capture.

Along with the rest of the Army of the Potomac, the Balloon Corps was on the run all through the ensuing Seven Days Battles. They abandoned their base at Gaines Mill in such a hurry they had to leave two gas generators behind. Without hydrogen, the deflated balloons were simply cargo, packed along on McClellan’s withdrawal to the James River. Lowe, shivering with malaria, turned the unit over to Allen and returned by boat to Washington, missing the Second Battle of Bull Run. Without the professor to stand up for them, the Balloon Corps’ wagons, mules, and gear were reclaimed by the Army Quartermaster. The unit never consisted of more than seven aeronauts, with a few specialists in gasbag varnishing, hydrogen generators, a repairman, and machinist, and also a rotating detachment of enlisted men subject to recall at official whim. Command was handed off among various junior staff officers. “I was subject to every young and inexperienced lieutenant or captain, who for the time being was put in charge of the Aeronautic Corps,” wrote Lowe on his return. “These young fellows had no knowledge whatever of aeronautics and were often a serious hindrance to me rather than a help.”

Lowe could not even reach Sharpsburg, Maryland, until the Battle of Antietam was over. “General McClellan remarked on several occasions that the balloon would be invaluable to him, and he repeated this to me when I arrived, assuring me that better facilities should be afforded me in future,” he wrote. “On this occasion he greatly felt the need of reports from the balloons, which … were perhaps not sufficiently valued.”

But having risen with McClellan, the Balloon Corps declined with him. Lowe’s ideas for high-resolution aerial photographic reconnaissance and using flares to signal across vast distances went nowhere. In April 1863, Captain Cyrus B. Comstock of the Army Corps of Engineers, to whom the Balloon Corps was relegated, was irked to learn the civilian professor was being paid as a full colonel, $10 per day. “Six dollars per day is ample payment for the duties he has to perform at present,” wrote the captain.

Lowe appealed all the way up to the office of commander Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, getting nowhere. At the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, a heavy storm damaged two of his balloons and destroyed much of his supplies of acid and iron trimmings for reinflating them. Comstock denied Lowe permission for their repair. It was the last straw. “As the battle was now over, I wished to be relieved, provided it was a suitable time,” wrote Lowe, “to which Captain Comstock replied that if I was going I could probably be spared better then than any other time.” Without its leader, the Balloon Corps fell into disuse and was disbanded that August.

“I have never understood why the enemy abandoned the use of military balloons early in 1863 after using them extensively up to that time,” wrote Confederate balloonist Alexander, whose Gazelle had been captured on the Virginia Peninsula. “Even if the observers never saw anything they would have been worth all they cost for the annoyance and delays they caused us in trying to keep our movements out of their sight.”

Though balloons would ultimately be outmoded on the battlefield, reconnaissance from on high is performed today by their technological successors, orbital spy satellites. Union commanders failed to exploit the air, but European observers did not. One German visitor to Lowe’s Civil War camp took the idea home with him and would develop hydrogen balloon warfare to its furthest extent. His name was Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments