By Chuck Lyons

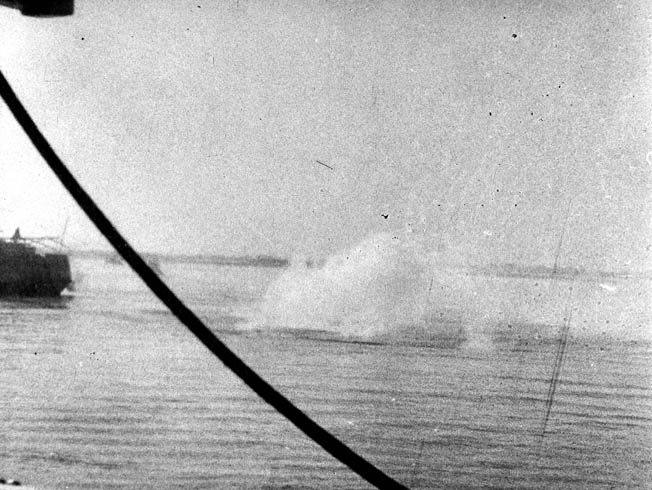

For some Americans, World War II started early. In December 1937, four years before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor propelled the United States into the war, Japanese planes attacked an American gunboat, the USS Panay, on China’s Yangtze River, strafing and bombing the boat, sinking it, killing three American crew members, and the wounding 45 others.

Those same Japanese planes also attacked three Standard Oil tankers that were being escorted by the gunboat, killing the captain of one of the tankers as well as a number of Chinese passengers.

Two newsreel cameramen aboard the Panay were able to film the attack and subsequent sinking of the gunboat, the burning tankers, and the diving, firing Japanese planes. The attacks and the newsreels taken at the time helped to turn American public opinion against Japan and, for a time, there was talk of war.

In the end, war was avoided, and Japan paid an indemnity of over $2 million to the United States. But, at the time and for years afterward, questions raised by the incident remained unanswered.

What had really happened? And why?

As early as 1854, the United States had gunboats on the Yangtze River, a right granted by treaty. By the 1870s, American interests in the area had expanded and the U.S. Asiatic Fleet was created to protect those interests from feuding Chinese warlords and pirates along the river.

By the early 1900s, Standard Oil’s activity and use of tankers in the region had also picked up, and by 1914 the United States Navy had introduced specially built, shallow-draft gunboats to the river. By then the Navy was patrolling as far upriver as Chunghink, 1,300 miles from the coast.

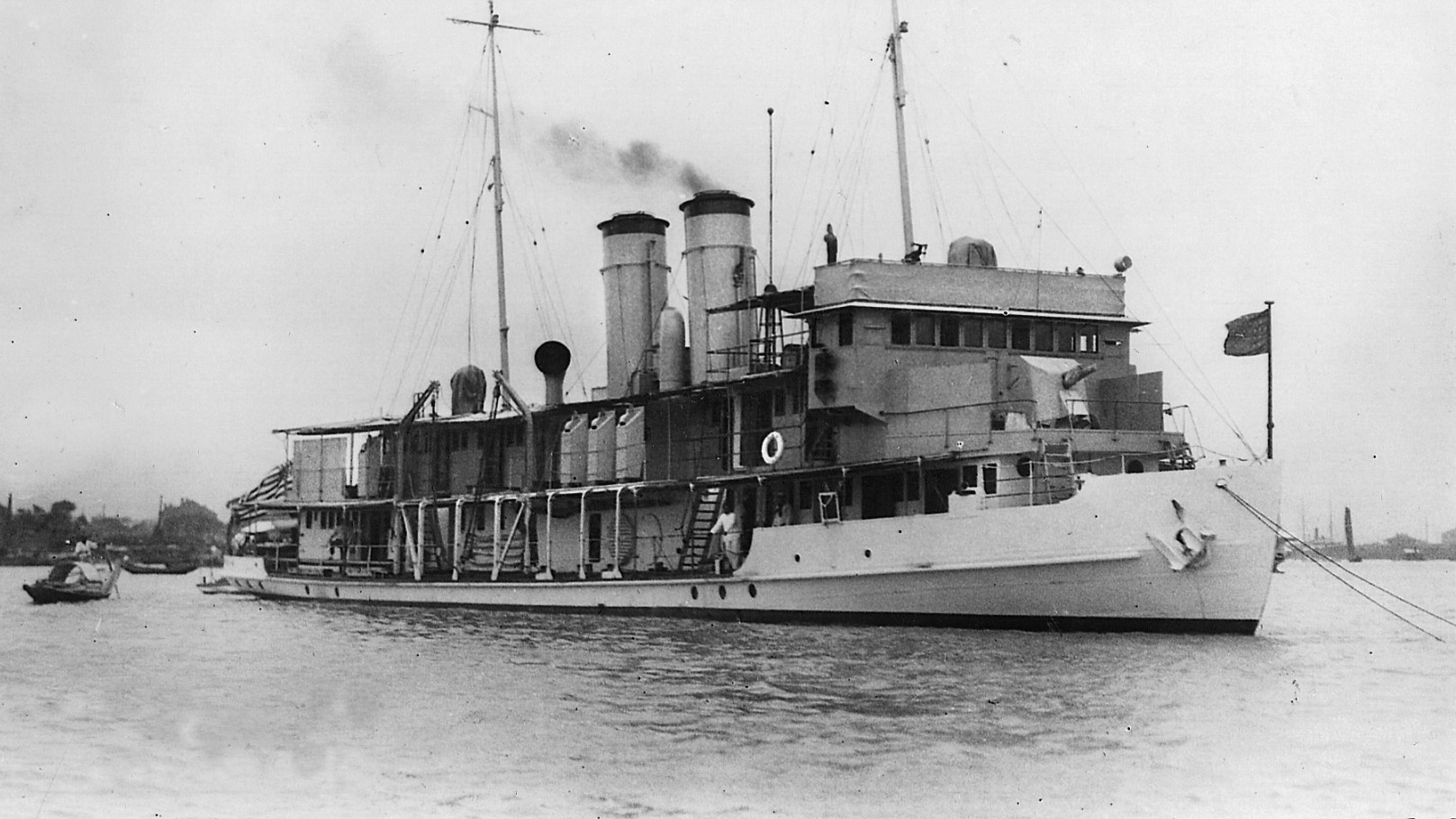

Between 1926 and 1927, six new gunboats were commissioned and placed on the river. One of the was the Panay, a 191-foot gunboat armed with eight. 30-caliber Lewis machine guns and two three-inch guns.

A brass plaque in the Panay’s wardroom summed up her mission: “For the protection of American life and property in the Yangtze River Valley and its tributaries, and the furtherance of American good will in China.”

In July 1937, following decades of diplomatic and military incidents between the two countries, increasingly hostile Japan attacked China. By November, the Japanese had captured Shanghai at the mouth of the Yangtze and had begun moving up the river, leaving “a swath of destruction.” In early December, Imperial troops were approaching Nanking, then the Chinese capital.

The United States was officially neutral in the conflict. Ambassador Joseph Grew and the staff of the American embassy fled the city in November, leaving four men including Vice Consul J. Hall Paxton behind to monitor the situation and do what they could to protect American citizens still in the area.

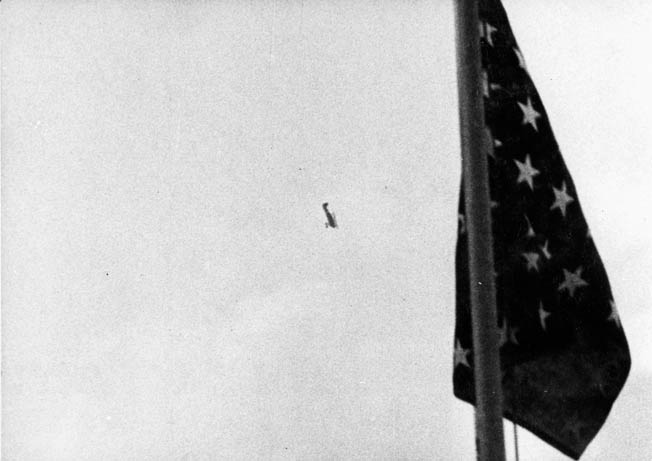

In early December, the Panay was sent from Shanghai to Nanking to remove the remaining Americans from the city. To prevent his gunboat being mistaken for an enemy vessel, Panay’s captain, Lt. Cmdr. James J. Hughes, ordered that American flags be lashed across the boat’s upper deck and that a 6 by 11 foot United States flag be flown from the boat’s mast.

Two sampans that were powered by outboard motors were attached to the Panay to ferry those being evacuated to the gunboat. Hughes also ordered that the two sampans conspicuously fly American flags.

By December 9, the Panay was docked in the river at Nanking and 15 civilians had been taken on board—the four embassy staffers, four other U.S. nationals, and other foreign nationals including a number of journalists. Among the journalists were newsreel cameramen Norman Alley of Universal News and Eric Mayell of Fox Movietone.

At the time, the gunboat had a crew of five officers and 54 enlisted men. As the Japanese approached the city and shells began falling near the river, the Panay left the city and moved to an oil terminal a short distance upriver. Hughes sent a radio message to the Japanese alerting them to its new position.

“That night all of us stood and watched the burning and sacking of Nanking, until we rounded the bend [in the river] and saw nothing but a bright red sky silhouetted with clouds of smoke,” Alley later wrote.

On December 11, shells began falling near where the Panay and three Standard Oil tankers, the Meiping, Meian, and Meihsia, were anchored; the tankers were there to help evacuate Standard Oil employees and agents from Nanking. The three tankers and the Panay quickly formed a convoy and moved seven miles farther upriver to avoid the shelling.

Witnesses to the action later claimed that the shells that had fallen appeared to be “aimed.”

On the morning of December 12, as the convoy was heading upriver, a Japanese naval officer approached the ships and demanded information from the Panay about the Chinese disposition of forces along the river.

Captain Hughes refused to comply. “This is an American naval vessel,” Alley reported Hughes as saying. “The United States is friendly to Japan and China alike. We do not give military information to either side.”

The convoy was then allowed to resume its passage upriver and eventually anchored 28 miles north of Nanking. Once there, Captain Hughes sent his new position to American authorities with a request that the information be relayed to the Japanese.

At about 1:40 pm that day, three Yokosuka B4Y Type-96 bombers were seen heading toward the convoy in V-formation. Japanese bombers overhead were a familiar sight to the men of the Panay. They had seen them frequently since the Chinese-Japanese fighting had begun, and the planes had never been anything to be concerned about.

“We had no reason to believe the Japanese would attack us,” Executive Officer Lieutenant Arthur Anders later said. “The United States was a neutral nation.”

This time was to be different.

To be safe, Captain Hughes summoned his men to battle stations and closed the gunboat’s water-tight doors and hatches. As the planes approached, however, they were joined by several Nakajima A4N Type-95 biplane fighters. The Yokosuka bombers seemed to be losing altitude or even going into power dives.

Suddenly and unexpectedly, they released their bombs.

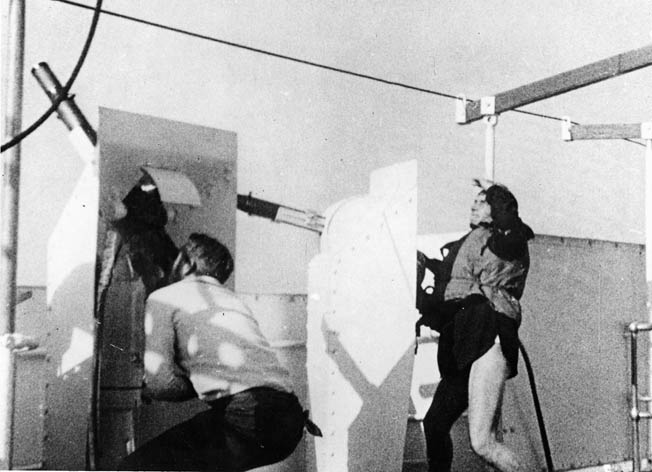

One of the bombs almost immediately hit the Panay’s pilot house. There was a brilliant flash and the sound of crunching steel and shattering glass. Captain Hughes was quickly incapacitated with serious wounds, the Panay’s three-inch guns were knocked out, and its pilot house, radio room, and sick bay were destroyed. The ship’s propulsion gear was damaged. Electrical power was out.

Not realizing Captain Hughes had been wounded, Anders nonetheless gave the order to return fire.

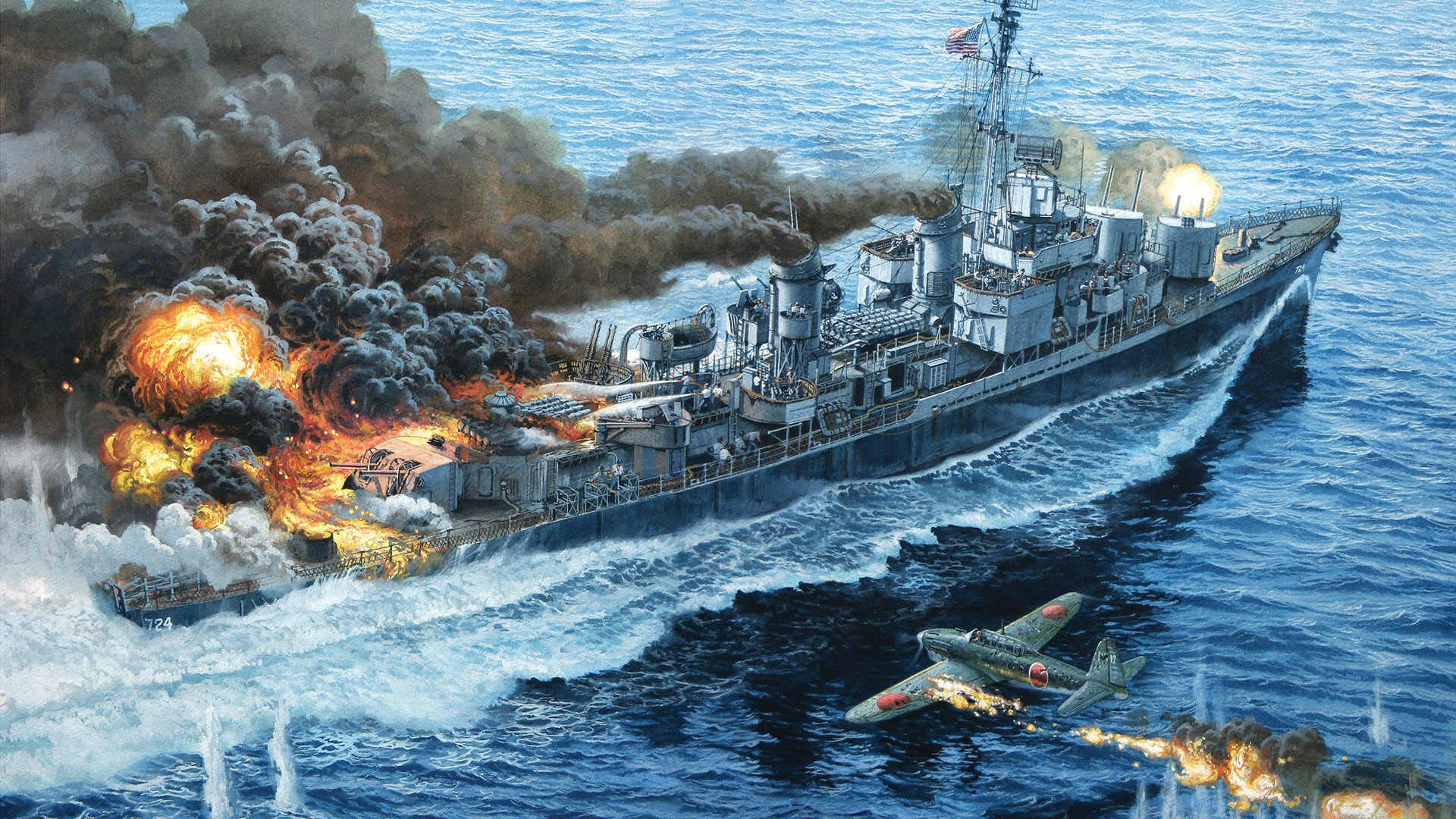

Following the three Japanese bombers, the Yokosuka fighters strafed the gunboat while six single-engine dive bombers swept over the Panay, pounding it with more heavy explosives. The Panay began to settle at the bow and list to starboard.

The crew returned fire as best they could, but the gunboat’s three-inch guns were down and her machine guns had been installed to fight targets on shore. Forward fire was almost impossible, and they could not be elevated enough to fire at the Japanese planes as they passed overhead. In addition, with many of the crew wounded, not all the guns could be manned. An Italian correspondent also had been struck and was critically injured.

Anders manned one of the guns himself but, when he became aware that Captain Hughes had been injured, he moved to the bridge to assume command. He was almost immediately struck in the throat by a shard of metal. Unable to speak and bleeding badly, he nonetheless wrote out orders in his own blood.

Throughout the chaotic scene, as bombs were exploding and machine-gun fire from the Japanese fighters strafed the boat, Alley and Mayell raced around the deck filming the action. Across the water, fire could be seen breaking out on the tanker Meiping.

On the Panay, crewmembers were throwing gas cans over the side and moving the wounded to the engine room. Twenty minutes into the attack, Anders said later, “Part of the [Panay’s] main deck was awash, the ship was slowly sinking and there were many injured on board.”

He gave the order to abandon ship.

The Panay had no lifeboats and one of its two motor sampans had already left the ship and was heading away. A Japanese plane came down on the sampan “like a chicken hawk,” Anders recalled. The plane dropped a bomb that fell short, but another Japanese plane came by and strafed the sampan before it could return to the gunboat.

The wounded—including Captain Hughes—were evacuated in the sampans, code books were destroyed, and lifebelts were distributed. Some crewmembers leaned wooden tabletops against the rails in case a quick exit was required. The stiff current in the river, which was as much as seven miles per hour, made it dangerous for swimmers. Most of the crew was able to leave on the sampans, however.

“The sampan I was in had been strafed, Anders later said, “on one of its many previous trips ashore. The bullet holes in the bottom were leaking water.”

Meanwhile, the Japanese had focused their attack on the Standard Oil tankers. On board the Meian, Captain C.H. Carlson had been killed and two of the three tankers were burning. “We could hear the pitiful screams of the Chinese crew members,” Norman Alley wrote.

At about 3:55 pm, the Panay sank in 10 fathoms.

The gunboat survivors, meanwhile, had reached shore. Many of them were wound-ed, and they huddled in the reeds along the shore as Japanese planes “soared in vulturous circles above us,” as Alley put it.

The two Standard Oil tankers burned on the river. The third tanker had by then beached itself.

Fearing they would be discovered by the Japanese, Alley wrapped the film he had shot, along with Mayell’s film, in canvas and buried the package in the mud. By dark, the attack was over, and the group of survivors realized they were in Chinese-controlled territory and about eight miles from Hoshien, a small fishing village. They made litters from whatever was available and walked the eight miles to the village, carrying the wounded.

The Panay had suffered three crewmen killed and another 45 injured. Five of her civilian passengers were also wounded.

Once at Hoshien, the survivors were able to contact American embassy officials, and American and British Navy vessels were immediately dispatched to the area. The Japanese authorities, expressing confusion over what had happened, also took part in rescue efforts, launching search planes and ships.

The survivors were finally picked up at Hoshien by the American gunboat Oahu and by two British gunboats, HMS Bee and HMS Ladybird, which had been fired on earlier by Japanese artillery. The British had suffered one man killed and four injured.

The Japanese quickly issued an apology, claiming they had received information that some of the Chinese fleeing Nanking were on the river and, from the altitude at which their bombers were flying and “in the mist,” their pilots had mistaken the Panay and the tankers as the vessels carrying the Chinese.

Secretary of State Cordell Hull issued a formal complaint.

The Japanese continued to apologize, a Japanese admiral resigned in connection with the incident, and Japanese Emperor Hirohito announced that he would personally take charge of an investigation of the incident “no matter how humiliating [it] may be to the armed forces.”

On December 19, Alley’s and Mayell’s film of the incident, which had been recovered from its hiding place on the Yangtze river bank, was released. The film put lie to Japanese claims that the Panay was not well marked and that visibility was limited. It showed a clear and sunny day.

Public outrage followed—President Franklin D. Roosevelt said he was “shocked”—and the attitude of the American people began to turn against the Japanese.

A few days later, as the Panay survivors reached civilization, “filthy, cold, and wearing only blankets, Chinese quilts, and tatters of clothing,” their photos and stories began being published and public outrage mounted.

Before Alley’s film was made public, however, Roosevelt had viewed it and had requested that the cameraman remove 30 of the 53 feet he had shot. Those 30 feet showed Japanese planes attacking the Panay at almost deck level and contradicted many of the Japanese government’s claims. In censoring the film, Roosevelt probably acted from fear that the explosive nature of the film would inflame the growing public sentiment in favor of war with Japan, something Roosevelt did not want at that time.

As the initial shock faded, things began to slowly return to normal.

Alley shifted his attention to the fighting in Europe. Lieutenant Anders amazingly coughed up a metal shard three days after the attack and regained the ability to speak; he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his actions. Captain Hughes had suffered a severely broken femur but would recover to serve in the coming war.

But why had the Japanese planes attacked the Panay and the Standard Oil tankers in the first place?

As late as 1953, Commander Masatake Okumiya, who had led the Japanese bombers that day, continued to maintain that the attack had been a case of mistaken identity. The pilots operating the bombers, he said, had only been flying in China for about eight days and had never been briefed on how to recognize neutral ships. The firing against the two British gunboats had been quickly ended, he said, when a British flag was spotted on one of the boats.

At the time and later, this explanation was questioned.

The Panay was known to be well marked and, despite Japanese claims, visibility was also known to be good that day. Alley’s film also showed that the Japanese planes had approached at a very low altitude, almost “deck high.” In addition, analysts asked, if the Japanese truly believed they were attacking troop transports, why did they clearly attack the Panay first—the only vessel capable of returning fire?

It was also reported after the war that U.S. Navy cryptographers had intercepted Japanese radio messages to the attacking planes indicating they were under orders during the attack and that the attack was in no way unintentional. Allegedly, some of the Japanese aviators involved had protested their orders before finally agreeing to execute them.

The most probable explanation of what happened to the Panay that day is that the Japanese government did not sanction the attack. Analysts and American newspapers speculated at the time—and later historians have agreed—that the attack was most likely launched by radical elements within the Japanese military that were trying to provoke a war with the United States.

Or it may have been an attempt by those same radical elements to measure the U.S. response to an attack, or was simply intended to force the United States to abandon its presence in China.

In any case, it was rogue Japanese officers who were behind the attack, not the Japanese government. The chaos spawned by the Japanese attack of Nanking may have provided what those elements considered an opportunity to further their own aims. They almost succeeded.

The prospect of war with Japan and the possibility of abandoning China both gained some public traction following the attack and its resulting publicity. A Los Angeles Times editorial at the time, for example, suggested, “A gradual withdrawal form China is no doubt wise.”

But the United States did not abandon China, and it did not go to war.

Roosevelt accepted an official Japanese apology for the incident. The Japanese government paid an indemnity of $2,214,007.36 to the United States in April 1938, and the United States declared the incident officially closed.

When it did so, one historian wrote, “A sigh of relief passed over the length and breadth of America.”

There would be no war with Japan—at least not then.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments