By Michael Collins & Martin King

In the first installment, a large German force made a surprise counteroffensive against American positons along the Belgian-German border—an operation that became known in the West as “the Battle of the Bulge.” In this conclusion, some SS troops, in their ruthless desire to succeed at all costs and perhaps force the Allies to reconsider their demands for unconditional surrender, executed Belgian civilians and U.S. soldiers who had surrendered.

It is not our intention to write the definitive account of the events; they have already been covered from virtually every angle. Later in this article there are references to the Malmédy Massacre as it was reported to soldiers in the field at the time, and it is their perspective that we will focus on.

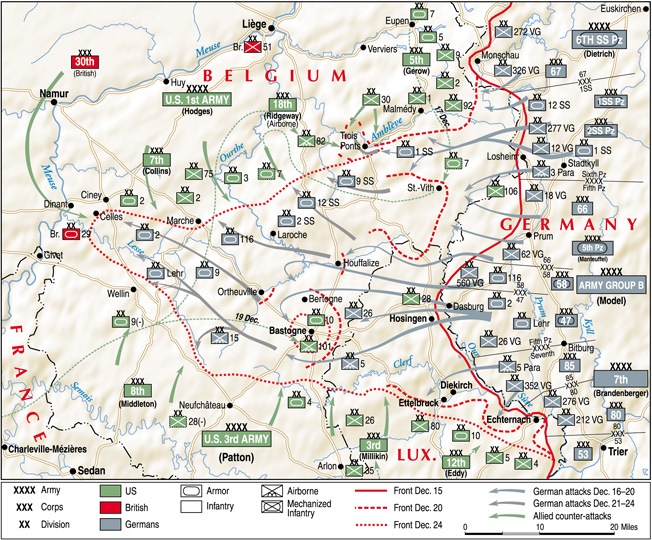

The German Pincer

While the “Battling Babies” of the 99th U.S. Infantry Division fought with every ounce of strength they could muster in the north, the 106th (“Golden Lion”) Infantry Division reported at 1:15 pm on December 16, 1944, that it could no longer maintain contact at the interdivision boundary, and by this time observers had seen strong German forces pouring west through the Lanzerath area.

Panic and chaos began to take hold as the young U.S. defenders of a very thinly held line began to feel the extent and ferocity of this German attack. The intelligence section of the 106th Division staff analyzed the enemy plan correctly in its report on the night of December 16: “The enemy is capable of pinching off the Schnee Eifel.”

In actual fact, only one German division, the 18th Volksgrenadier, formed the pincers poised to grip the 106th Division. After all, the entire 62nd Volksgrenadier Division stood poised to break through in the Winterspelt area and to strengthen or lengthen the southern jaw of the pincers. Through the early, dark hours of the 17th, the enemy laid down withering mortar and artillery fire on the frontline positions of the 424th Regiment of the 106th Division.

While the German forces pounded away relentlessly on the Schnee Eifel and at the harassed defenders of the Elsenborn Ridge, the 1st SS Division poured through the Losheim Gap virtually unmolested. General Courtney Hodges, CG of First Army, decided to plug the southern approaches to the ridge with his tried and tested veterans of many campaigns from North Africa to Normandy. The Germans knew of the 1st Infantry Division. At that moment, the Big Red One was recuperating after being engaged in heavy fighting during the November offensive and was spread out as far south as Paris. The troops were hastily summoned to report for duty on the morning of the 17th. By the evening, they were speeding north to protect the southern flank of the Elsenborn Ridge and relieve pressure on the 99th Division.

It should be noted here that one of the most prominent features of the U.S. Army in 1944 was its capacity to displace from one location to another at great speed. Speed and mobility were going to prove key factors in this offensive. The 82d Airborne Division was located at Camps Suippes and Sissonne, France, undertaking normal ground divisional training when, on December 17, 1944, first orders were received to move to the east. Maj. Gen. James M. Gavin received a phone call while at dinner with his staff, stating that SHAEF considered the situation at the front critical and that the airborne divisions were to be prepared to move 24 hours after daylight the following day, December 18.

On both sides of the battle, line reinforcements were on the move, the Germans to close the pincer on the Schnee Eifel troops, the Americans to wedge its jaws apart. The battle had continued all through the night of December 16-17, with results whose impact would only be fully appreciated after daylight on the 17th.

Massacres of the Bulge

Colonel Mark Devine, the 14th Cavalry Group commander, left the 106th Division command post about 8 am on December 17 without any specific instructions. The previous evening, V Corps had asked VIII Corps to reestablish contact between the 99th Division and the 14th Cavalry. This call had been routed to Colonel Devine, at St. Vith, who spoke on the phone to the 99th Division headquarters and agreed to regain contact at Wereth—a town that was to become the scene of one of the most brutal massacres of World War II.

December 17 would go down in history as the day that the Malmédy Massacre occurred, perpetrated by members of Kampfgruppe Peiper. But that was not the only massacre that occurred on that frozen December day in 1944. Eight GIs were murdered at Ligneuville just outside the Hotel du Moulin, and 11 African American GIs suffered the same fate at Wereth.

Participation by African American GIs in the Battle of the Bulge is not well known or recognized. The majority of the African American GIs in World War II, 260,000 in the European Theater of Operations, were simply never acknowledged. They are the “invisible” soldiers of World War II. They included 11 young artillerymen of the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion who were murdered by the SS after surrendering. The 333rd Field Artillery Battalion was a 155mm howitzer unit that had been in action since coming ashore at Utah Beach on June 29, 1944. Typical of most segregated units in World War II, it had white officers and black enlisted men.

At the time of the Battle of the Bulge, the unit was located in the vicinity of St. Vith, Belgium. Specifically it was northeast of Schönberg and west of the Our River in support of the U.S. Army VII Corps and especially the 106th Infantry Division. By the morning of December 17, German troops and armor were penetrating virtually all sectors of the thinly held line. While many personnel tried to escape through Schönberg, 11 men of the service battery went overland in a northwest direction in hopes of reaching American lines.

Murder at Wereth

At about 3 pm, they approached the first house in the nine-house hamlet of Wereth, Belgium, owned by Mathius Langer. The men were cold, hungry, and exhausted after walking cross-country through the deep snow. They had two rifles between them. The family welcomed them and gave them food. But this small part of Belgium did not necessarily welcome Americans as “liberators.”

This area had been part of Germany before World War I, and many of its citizens still saw themselves as Germans and not Belgians. The people spoke German but had been forced to become Belgian citizens when their land was given to Belgium as part of the poorly assembled Treaty of Versailles. Unlike the rest of Belgium, many people in this area welcomed the Nazis in 1940, and again in 1944, because of their strong ties to Germany.

Mathius Langer was not one of these, however. At the time he took the black Americans in, he was hiding two Belgian deserters from the German Army and had sent a draft-age son into hiding so that the Nazis would not conscript him. A family friend was also at the house when the Americans appeared. Unfortunately, unknown to the Langers, she was a Nazi sympathizer.

About an hour later, a German patrol of the 1st SS Division, belonging to Kampfgruppe Hansen, arrived in Wereth. It is believed that a Nazi sympathizer (possibly the Langer family’s friend) informed the SS that there were Americans at the Langer house. When the SS troops approached the house, the 11 Americans surrendered quickly, without resistance. The Americans were made to sit on the road, in the cold, until dark. The Germans then marched them down the road. Gunfire was heard during the night.

Classified “Secret”

In the morning, villagers saw the bodies of the men in a ditch. Because they were afraid that the Germans might return, they did not touch the dead soldiers. The snow covered the bodies, and they remained entombed in the snow until mid-February, when villagers directed a U.S. Army Graves Registration unit to the site. The official report noted that the men had been brutalized, with broken legs, bayonet wounds to the head, and fingers cut off. Prior to their removal, an Army photographer took photographs of the bodies to document the brutality and savagery of this massacre.

An investigation began immediately with a “secret” classification. Testimonies were taken from the Graves Registration officers, the Army photographer, the Langers, and the woman who had been present when the soldiers arrived. She testified that she told the SS the Americans had left. The case was then forwarded to a War Crimes Investigation unit. However, the investigation showed that no positive identification of the murderers could be found (i.e., no unit patches, vehicle numbers, etc.), only that they were from the 1st SS Panzer Division.

Remembering the Massacre

By 1948, the “secret” classification was cancelled and the paperwork filed away. The murder of the 11 soldiers in Wereth was seemingly forgotten and unavenged. Seven of these unfortunate men were buried in the American cemetery at Henri-Chapelle, Belgium, and the other four bodies were returned to their families for burial after the war ended. It is remarkable to know that the identities of the Wereth 11 remained unknown, it seemed, to all but their families.

Herman Langer, the son of Mathius Langer, who had given the men food and shelter, erected a small cross with the names of the dead in the corner of the pasture where they were murdered, as a private gesture from the Langer family. But the memorial and the tiny hamlet of Wereth remained basically obscure and were not listed in any guides or maps to the Battle of the Bulge battlefield. Even people looking for it had trouble finding it in the small, German-speaking community.

In 2001, three Belgian citizens embarked on the task of creating a fitting memorial to these men and additionally to honor all black GIs of World War II. There are now road signs indicating the location of the memorial.

Combat Engineers at Malmédy

As Battle of the Bulge got under way, the members of the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion were among the many engineer battalion soldiers who picked up rifles and fought off the German assault. Throughout the war, the Germans feared and detested the American engineer battalions because not only could they blow up bridges, they could fight off German soldiers just like the infantry. The engineers even had the capacity to take out tanks with explosives and dynamite—these guys implemented multitasking long before it became a contemporary buzzword.

After the German Army began its thrust through the Ardennes, the 291st was sent to Malmédy and ordered to hold the town at all costs. The engineers set up a series of roadblocks in and around Malmédy, where there were only about 128 men holding the line against the whole Sixth Panzer Army. Their initial roadblocks would be the only barriers between Kampfgruppe Peiper and the roads toward the Meuse River. Since most of the U.S. Army was in disrepair after the first day of the Bulge, the engineers would have to make do with what they had to buy the rest of the American forces time to regroup.

Ralph Ciani of Company C, 291st Engineer Combat Battalion, swept for mines and was involved in many different actions the 291st took part in during the Battle of the Bulge: “When we went into Belgium, we were working at a sawmill in Sourbrodt, and we thought we would be going home for Christmas. In the morning, we saw swastikas on the houses, and we heard shots being fired around but did not know what was happening. When they broke through, we got orders to go to Malmédy and hold it all costs. We went with a company of men, and the heaviest piece of equipment was a bazooka, with only a few mines.

“As we were pulling into Malmédy, there was an MP there, and he asked us, ‘Who are you guys?’

“‘Engineers,’ we replied.

“‘Well, good luck—I am getting the hell out of here,’ the MP replied. When we went into Malmédy, we did not know what to expect, and it was scary.”

Axis Sally

Frank Towers of Company M, 120th Regiment, 30th Infantry Division, said, “At about 10 pm the night of December 17, our division was ordered to move out—to where, no one seemed to know. Just follow the vehicle ahead of you! Soon, we were able to realize, by orienting on the stars above, that we were moving south, but to where and why were still big questions.

“Finally, in the early hours of the morning, with some of the men still awake and partially conscious and listening to the American Forces Network on their radios, there was a break-in on that frequency by our nemesis and rumor monger, ‘Axis Sally,’ the major German propagandist, who informed us, ‘The 30th Infantry Division, the elite Roosevelt’s SS Troops and Butchers, are en route from Aachen to Spa and Malmédy, Belgium, to try to save the First Army Headquarters, which is trying to retreat from the area, before they are captured by our nice young German boys.

“‘You guys of the 30th Division might as well give up now, unless you want to join your comrades of the First Army HQ in a POW camp. We have already captured most of the 106th Division and have already taken St. Vith and Malmédy, and the next will be Liege.’ We were stunned, since only then did we have any clue as to where we were going, or the reason for this sudden movement.

Hope From P-47s

John Hillard Dunn, Company H, 423rd Regiment, 106th Division, recalled, “There was a strange quiet Sunday morning the 17th. No rolling thunder of a dawn barrage. A false and temporary optimism … from the west we heard planes.

“A couple of former Air Force men were overjoyed and not above rubbing it in that the planes were coming to our rescue. Then we saw that the P-47s were dumping their loads a long way to our rear. Now we knew that somewhere back there the German spearhead was grinding along.

“But the P-47s gave us hope that we might be able to break through and reach whatever American forces lay to the west. Clouds gathered swiftly, and a steady, soaking rain was falling by noon, turning knee-deep snow into ankle-deep mud. Those former Air Force smart alecks didn’t have to tell us that the ceiling was zero and that the P-47 fliers whose luck hadn’t run out were back swigging coffee someplace in France.

“Rumors were thicker than rain clouds that afternoon, and as we wallowed about in mud, moving aimlessly from one place to another, we heard that an armored division was battering its way through to us and that we could expect to see Georgie Patton racing around the corner any minute.

“By evening the magnitude of the German effort was more apparent. GIs with ‘rear echelon’ patches on their shoulders—and a hunted look in their eyes—began showing up and offering us the clothes off their backs if we would trade an M-1 for a .45-caliber pistol.”

Dunn continued, “Sunday night is still a nightmare. We holed up in a pinewood, putting our still-present prisoners in a three-sided wooden stockade. Two men were assigned to guard them in four-hour reliefs. Another newly made MP and I had a relief to midnight. As we stood there in the drenching rain, he talked almost hysterically of his wife and four children. He’s cracking, I thought. Now and then a prisoner wise-cracked in German.

“It was necessary for me to leave the stockade to check on our relief. As I returned to the stockade, I could hear muttering and moaning in the darkness. I thought one of the Heinies was sick. But when I drew up to the tall pine that I had used to mark our position, I realized that the moans were from my companion.

“He was on his knees in the snow. His hands were raised, and he was crying and praying in a loud, piercing wail. What he had done with his weapon, I don’t know. The Heinie prisoners were stirring and jabbering. I had to do it. I swung with my fist as hard as I could on my kneeling buddy.”

10th Armored Division on High Alert

Harold “Stoney” Stullenberger, C Company, 55th Armored Engineer Battalion, 10th Armored Division, noted, “Two or three of us were in some little town near Metz. It was pretty cold, but we had a chance to take a bath in a stream. It was about 3 o’clock in the afternoon. A runner came down there and told us we had to get back and get our gear and get ready. We had no idea where we were going.

“That first night I stayed in a schoolhouse in Arlon with my platoon, and then the following day we moved toward Bastogne. We went there around 5 or 6 o’clock, and it was quiet. There was no activity at all. We then moved up to Magaret and stopped between there and Longvilly. The head of the column was all the way up at Longvilly. Our second squad, Wayne Wickert was the sergeant; they were 500 yards ahead of us. It became dark that first night, and there were a lot of stragglers coming back from the 9th Armored and the 28th Infantry. They changed the password on us about three or four times, so we figured something was going on, but we still had no idea. So we sat there all night.”

John Kline, M Company, 423rd Regiment, 106th Division, commented, “German activity was reported along our front the 17th (remember the Bulge started on the 16th). The commander called me back to the command post. He informed me that I should be prepared to move my gun to his area to protect the command post.

“While visiting with him, I noticed that he was very nervous. His .45 Colt pistol was on the table, ready for action. Our master sergeant, who was also present, seemed equally concerned. Later, I was to learn the reason for their anxiety. I suspect, in retrospect, that they had been made aware of the German breakthrough yet did not yet know the importance of the news.

“While in the vicinity of the command post bunker, I watched a U.S. Army Air Corps P-47 Thunderbolt chase a German Messerschmitt Me-109 through the sky. They passed directly in front of us. Our area being one of the highest on the Schnee Eifel gave us a clear view of the surrounding valleys. The P-47 was about 200 yards behind the Me-109 and was pouring machine-gun fire into the German plane. They left our sight as they passed over the edge of the forest. We were told later that the P-47 downed the Me-109 in the valley. As it turned out, my machine gun was not moved to the command post.

“During the night of the 17th we heard gunfire, small arms, mortars, and artillery. We also could hear and see German rocket fire to the south. The German rocket launcher was five-barreled and of large caliber. The rocket launcher is called a Nebelwerfer. Due to their design, the rockets make a screaming sound as they fly through the air. Using high explosives, but not very accurate, they can be demoralizing if you are in their path of flight.”

Captured by the Germans

Clair Bennett of Company F, 90th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron (Mechanized), 10th Armored Division, said, “As we traveled up from Sierck, France, we stopped for about 15 minutes around 12 o’clock. I did not intend on going to sleep, but I fell asleep. First thing I know someone kicked me in the back down in the turret, I roused, and there’s no doubt that I used the aircom in the tank, which we had for communications, since naturally you can’t see each other all the time.

“With the noise and whatnot, it is virtually impossible to hear each other. I said, ‘What do you want? What’s the problem?’ And George Sutherland, the tank commander, said, ‘I’ve been trying to wake you up for the last 20 minutes!’

“As we continued onward we came to a place, and we were getting pretty darn close to our location. I lost track of the blackout lights, since you can only see for 50 or 75 feet. I cut across, and I went through a grove, and I started to go toward a ravine. I went through a German bivouac area, but I finally got back on the road. I could see where other tanks had been, but I was exhausted, there was no question about it.”

Nelson Charron, Company D, 422nd Regiment, 106th Division: “December 17th, we continued to fight; there was nothing else we could do. We all wanted to fight; it was either be captured or killed. The officers told us to surrender, and we had to destroy our weapons. On their tanks they had 88s, and anybody who tried to escape was shot. There was a group who tried to get out, but they did not make it because of those 88s.

“At first we walked. There were 3,000 of us who were captured, and we walked and walked for about a day and a half, and we were put in boxcars. One night we were bombed by the British, and the Germans locked us in the boxcar, and they left, but they left us to be bombed. Some of the cars were hit, and we lost some men there. The next day, the Germans came back, and then we continued on to Stalag IX-B. They took all the Jewish boys, and they took them down the road and shot them. They massacred them. Just in our barracks there were maybe 10 or 15 of them.”

“Sounds Like a Name That You Might Find in a History Book- Bastogne”

William “Richard” Barrett with the 420th Field Artillery Battalion, 10th Armored Division, recalled, “The next morning we mounted up again and headed out. On the way up there I remember seeing a sign on the side of the road. I was in my machine-gun position, and Corporal Dillon was on the other side of the tank. I said, ‘Dillon, that sounds like a name that you might find in a history book—Bastogne, 14 kilometers.’

“That afternoon we pulled through Bastogne, people standing around, watching us drive through, and headed out north and east, set up in the firing position like we normally did out in a field. We got everything set up and got our ammunition ready to go—no firing mission because it was foggy and you couldn’t see nothing. They had a sergeant call there. He called all the section chiefs and told them to keep everything because we might have to move fast.”

Withdrawing the Artillery

John R. Schaffner noted, “The 2nd Battalion of the 423rd Infantry Regiment, in Division Reserve, was ordered to hold positions in front of the 589th [Field Artillery Battalion] while it withdrew to the rear. Meanwhile, the 589th held on in the face of heavy small-arms and machine-gun fire until the infantry was able to move into position shortly after midnight.

“About 0400 on the morning of December 17 our battalion was ordered to move out to the new position. By now the enemy was astride the only exit for the C Battery position so that it was unable to move. The battalion’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Kelly, and his survey officer stayed behind and tried to get infantry support to help extricate this battery, but they were not successful. The infantry had plenty of its own problems.

“C Battery was never able to move and was subsequently surrounded, and all were taken prisoner. While all this was happening, I was given orders by Captain Brown to take a bazooka and six rounds and, with Corporal Montinari, go to the road and dig in and wait for the enemy attack from ‘that’ direction. This we did and were there for some time waiting for a target to appear where the road crested. We could hear the action taking place just out of sight, but the battery was moving out before our services with the bazooka were required.

“As the trucks came up out of the gun position, we were given the sign to come on, so Montinari and I abandoned our hole and, bringing our bazooka and six rounds, climbed on one of the outbound trucks. I did not know it at the time, but my transfer from A Battery to B Battery was a lucky break for me, since Captain Menke, A Battery’s commanding officer, got himself captured right off the bat, and I probably would have been with him.

“A and B Batteries moved into the new position with four howitzers each, the fourth gun in A Battery not arriving until about 0730. Lieutenant Wood had stayed with the section as it struggled to extricate the howitzer with the enemy practically breathing on them. Battalion headquarters commenced to set up its command post in a farmhouse almost on the Belgian-German border, having arrived just before daylight.

“At about 0715 a call was received from Service Battery saying that they were under attack from enemy tanks and infantry and were surrounded. Shortly after that the lines went out. Immediately after that a truck came up the road from the south, and the driver reported enemy tanks not far behind.

“All communications went dead, so a messenger was dispatched to tell the A and B Batteries to displace to St. Vith. The batteries were notified, and A Battery, with considerable difficulty, got three sections on the road and started for St. Vith. The fourth piece again, however, was badly stuck, and while attempting to free the piece, the men came under enemy fire. The gun was finally gotten onto the road and proceeded toward Schönberg. Some time had elapsed before this crew was moving.”

Under Fire From the Germans

“B Battery then came under enemy fire, and its bogged down howitzers were ordered abandoned, and the personnel of the battery left the position in whatever vehicles could be gotten out. I had dived headfirst out of the three-quarter-ton truck that I was in when we were fired on. I stuck my carbine in the snow, muzzle first. In training we were told that any obstruction of the barrel would cause the weapon to blow up in your face if you tried to fire it.

“Well, I can tell you it ain’t necessarily so. At a time like that I figured I could take the chance. I just held the carbine at arms length, aimed it toward the enemy, closed my eyes, and squeezed. The first round cleaned the barrel and didn’t damage anything except whatever it might have hit. As the truck started moving toward the road, I scrambled into the back over the tailgate, and we got the hell out of there.

“Headquarters loaded into its vehicles and got out as enemy tanks were detected in the woods about 100 yards from the battalion command post. Enemy infantry were already closing on the area. The column was disorganized. However, the vehicles got through Schönberg and continued toward St. Vith. The last vehicles in the main column were fired on by small arms and tanks as they withdrew through the town.

“As the vehicles were passing through Schönberg on the west side, the enemy, with a tank force supported by infantry, was entering the town from the northeast. Before all the vehicles could get through, they came under direct enemy fire.

The A Battery executive officer, Lieutenant Eric Wood, who was with the last section of the battery, almost made it through. However, his vehicle, towing a howitzer, was hit by tank fire, and he and the gun crew bailed out. Some were hit by small arms fire. Sergeant Scannipico tried to take on the tank with a bazooka and was killed in the attempt. The driver, Kenneth Knoll, was also killed there. The rest of the members of the crew were taken prisoner, but Lieutenant Wood made good his escape. His story has been told elsewhere. Several of the other vehicles came down the road loaded with battalion personnel and were fired on before they entered the town. These people abandoned the vehicles and took to the woods, and with few exceptions they were eventually captured.”

101st Airborne Division in Bastogne

By December 17, 1944, Allied intelligence had a slightly better idea of the strength and objectives of the attacking German forces. Under mounting pressure, General Eisenhower, at the request of Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges, the U.S. First Army commander, decided to commit his reserves: the XVIII Airborne Corps. Lt. Gen. James Gavin received notification that the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions had been alerted to move into action at daylight the following day and head, without delay, toward the town of Bastogne.

Lieutenant General Gavin left for Spa, Belgium, and a meeting with Lt. Gen. Hodges. On arrival, Gavin received more information regarding the latest situation and was ordered to attach the 82nd Airborne to V Corps and to bolster the defenses in the area of Werbomont, northwest of St. Vith—their mission to support existing units in the area and block the advance of the Sixth Panzer Army.

The 101st Airborne Division, under Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, established its headquarters in the town of Bastogne to reinforce the defense of this vital location. The troops in Reims boarded trucks and departed with all haste to their allocated positions. Many men were pulled from leave, and many others were devoid of proper equipment or arms, but they were notified that these would be collected at their destination, so they departed with all speed. By 8 pm on December 18, the lead elements of the 82nd had arrived in Werbomont, where they trudged through blizzard conditions along muddy, snow-blocked roads toward their defensive positions.

William Hannigan of the 82nd Airborne

William Hannigan, a member of H Company, 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, said, “We had come off the line for rest and kind of repair. We were in Ramerville [sic] in France when the Germans invaded the forest. And we were pulled out on trucks; inadequately armed and given, you know, clothes. We were just pulled out in necessity in this thing. Wasn’t well thought out, but we did get up on these trucks and were taken right up to Bastogne. My brother was at Bastogne [in the 101st Airborne], and I always told him that we saved his skinny little butt.

“Now we went up and were put in there. We had leadership in Lieutenant James Megellas, another special officer named La Riveriera, and Jack Rivers, and we had Ted Finkbeiner, an excellent leader. I asked him just recently, “How come you never had the fear that the rest of us had, normal fear?’ and he said, ‘I grew up in the swamps in Louisiana with a gun in my hand in the woods and the rivers hunting all the time.’ And he said he found great joy in it. And I thought, well, these people didn’t send us into battle … they led us, that was important.

“Now the battle is a confusion of things that I just know a very small amount about. A couple of things I remember are that toward the end we captured some Germans who’d been pulling back from the Battle of the Bulge, and I asked a noncommissioned officer (NCO) in the German Army, ‘Why when you knew you lost the war did you fight so viciously?’ And he said, ‘My family. For eight or ten years that’s all we had, one another, so we protected and fought viciously for one another.’ I thought it was interesting.

“First we got off the trucks in Werbomont and started moving north, and we had engagements then. It was a question of survival and lack of equipment, and they talked about getting two guys in a hole in the ground. They called it ‘dig a foxhole.’ Well, if three guys got in there and you slept ‘spoon fashion,’ the guy in the middle got warm, and you did that and turned it over. Now it sounds a little out of sync, but you did some things you normally wouldn’t do in order to survive. And I want to tell you that I spent a lot of years trying to forget this and I succeeded.”

“We Didn’t Know the Situation, We Just Knew it Was Cold”

The 101st arrived at 11:45 pm on December 18, and at daylight the next morning the soldiers began taking up positions at the roadblocks around Bastogne in support of Team Cherry, Team O’Hara, and Team Desobry at Noville under the command of the distinguished William R. Desobry. The 501st arrived first and moved into areas around Longvilly. The unit proved to be a stubborn barrier that would allow the necessary time to build Bastogne’s defenses.

Ralph K. Manley of the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne, said, “I was in Paris on a 24-hour pass after we just returned from Holland, and a loudspeaker came on saying, ‘All units report to your units immediately, as quickly as possible, any way possible.’ So, we returned then from Paris back to our unit and immediately got on what clothes we had. I still had on my Class A’s, of course, for being in Paris, and we loaded onto port battalion trucks—these semi trucks that had four-foot sidewalls on them and open tops—without overcoats and without overshoes and headed toward the Bulge, and it was very cold.

“We met troops that were coming out, wounded, walking as we crossed paths, us going in, and them coming out—those who were disenchanted, having been overrun by the Germans and so on—a truck with maybe a series of bodies on it, and as one rounded the corner, some of the pieces of bodies fell off the truck.

“At that time they had grouped together clerks, anybody who was a soldier, to go to the front, and some of those not having seen that just keeled over in their tracks because they had not seen that type of wartime before. We did not know actually what was going on. As we got back to our unit in Mourmelon, France, then we got our equipment and our guns and what have you and were on trucks in minutes, headed off to Bastogne.

“We didn’t know the situation, we just knew it was cold, and we had to go as we were without overshoes or overcoats. Again, with zero degrees, you can imagine—in open-air trucks, going there, put in like cattle you might say, on trucks that weren’t covered. They were actually port battalion trucks that were used to haul merchandise from the ships out to the warehousing areas, so that’s what we rode to Bastogne on.

“Once we got there, of course, it was just dismount and head up the road to the city, on foot. We just missed others as they were coming out—both wounded, disabled, and what have you, who were hobbling and going out in trucks, hauling bodies that had been killed and so on. That’s what we met as we were going into Bastogne.

“Being a demolitionist, I was out on the edge, in a foxhole. In this case, the ground was frozen, but we were in a barn lot with all the feces and cattle stuff, so it was easier to dig a foxhole there. You can imagine what I must have smelled like. We disabled some tanks that were coming through with the bazooka, but they got very close. Oftentimes you maybe had two in a foxhole, but in this case it was just one because the ground was so hard to dig, at least on the surface with the snow.

“Also, you didn’t want to reveal your position because of the black dirt on top of the white snow, so you had to get snow and cover over the soil that you had dug out of the foxhole.”

Defending the Ridge at Prumerberg

Out on the freezing Prumerberg just east of St. Vith, a few hundred members of the 168th Combat Engineers were fighting tooth and nail against the whole 18th Volksgrenadier Regiment, who were attacking their position with devastating ferocity. They had no idea how long they were going to have to hold that ridge.

One of those serving with the 168th Engineer Combat Battalion was James W. Hanney, Jr. For six long days and nights, Hanney and the rest of the 168th resisted sustained attacks of the determined enemy in the most inhumanly cold conditions. It was minus 18 degrees Fahrenheit on that small ridge, and they had to contend, not only with the Germans but also with a scythe-like wind that skimmed in across the icy hills of the Schnee Eifel. James was eventually wounded and helped down from the ridge by his best friend, Frank Galligan.

Some years ago, co-author Martin King accompanied Hanney and a few members of his family back to the battlefield. King said, “We even managed to locate what we believed to be the actual foxhole that he dug back in 1944. The soldiers of the battalion were ordered to dig in on the ridge just to the east of St. Vith and hold their positions until they received further orders. I recall asking him how on earth they managed to dig into that frozen ground up there on the ridge. ‘It was easy,’ he told me. ‘We just tossed hand grenades to loosen up the ground and then dug in.’

The Malmédy Massacre

Seventy years on, perhaps the best-known incidents in the entire Battle of the Bulge are the atrocities committed against both U.S. service personnel and Belgian civilians in December 1944, by a German unit known as Kampfgruppe (Battle Group) Peiper, an element of the Sixth SS Panzer Army.

The events that occurred in the small village of Baugnez, Belgium, in December 1944, are referred to in most history books as the Malmédy Massacre, despite the fact that Malmédy is about five or six kilometers east of the site.

Survivors of Battery B of the ill-fated 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, the unit that was unmercifully gunned down after having surrendered, have written and rewritten numerous accounts of their experiences, but what is not so readily available is the testimony of the perpetrators.

Endless testimonies about that particular atrocity have been given, and it has been covered at great length in many books about the Battle of the Bulge. That the massacre occurred is an indisputable fact of history, but the circumstances under which it occurred have been contradicted time and again.

One only needs to follow the line of progress (Rollerbahn D) of Kampfgruppe Peiper to see that it was not an isolated incident; other cold-blooded murders occurred along the route. In spite of this, this incident always appears to raise more questions than answers.

The Malmédy Massacre was a pivotal event that changed the psyche of the American soldier during the Battle of the Bulge. There were many massacres during the battle, but when 86 defenseless soldiers from the 285th were murdered in a field in Baugnez, Belgium, the war became even more personal for the average GI. The phrase “take no prisoners” became part of the American soldier’s motto.

Captured by the SS

Ted Paluch of Battery B, 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, was in one of the half-tracks that came under attack while the convoy headed past Baugnez to see how far Peiper’s advance had come.

Paluch recalled, “On December 17 we were in Schevenhutte, Germany, and got our orders to go. We were in the First Army; we got our orders to move to the Third Army. There was a tank column going with us, and they took the northern road and we took the southern road. That would have been something if they had gone with us south.

“Right before we left, a couple of guys got sick and a couple of trucks dropped out of the convoy, and they were never in the massacre. Also, there were about 15 sent ahead to give directions and all, and they escaped the massacre. From the massacre you saw guys … they got one guy named Talbert, I remember him, both arms, both legs, across the stomach. He lived to the next day.

“We had no idea that it was going to happen. We took a turn, like a ‘T’ turn, and the Germans were coming the other way. We were pretty wide open for I guess maybe half a mile, and their artillery stopped our convoy. We just had trucks, and all we carried was carbines. We might have had a machine gun and a bazooka, but that was about it; we were ‘observation.’

“They stopped the convoy. We got out, and the ditches were close to five or six feet high because I know when I got in it, the road was right up to my eyes. There was a lot of firing; I don’t know what we were firing at or who was firing at anything, but there were a lot of tracer bullets going across the road.

“Finally, a tank came down with the SS troopers behind it. They wore black, and on one collar they had a crossbones and skull and on the other collar they had lightning. They just got us out, and we went up to the crossroad, and they just searched us there to get anything of value—cigarettes, and I had an extra pair of socks, and my watch, everything like that. They put us in the field there that was their front line—ours was 21/2 miles away in Malmédy.”

Survival at Malmédy

“When we were captured and being brought up there, the people who lived there or in that general area brought up a basket. I guess it was bread or something, and they brought it up to them to eat. Every truck and half-track that passed fired into the group, and why I didn’t get hit too bad … I was in the front, right in the front, the first or second or third right in the front. Each track that came around the corner would fire right into the group in the middle so that they wouldn’t miss anything; that’s why I didn’t get too badly hit. We laid there for about an hour, maybe two hours. While we were lying there, they come around, and anyone who was hurt, they just fired and would knock them off.

“Someone yelled, ‘Let’s go!’ and we took off. I went down the road, there was a break in the hedgerow, and a German that was stationed there at that house came out and took a couple of shots at me, and I got hit in the hand. If he saw me or not I don’t know, he went back and didn’t fire at me anymore. I was watching him come, and there was a well, and I went over there. It was all covered up, and I laid down.

“There was a little hill right behind where I was, and I just rolled. I got there … near a railroad, and I figured it would take us somewhere. I met a guy from my outfit, Bertera, and two other guys—one guy from the 2nd Division, he was shot, and another guy from the 2nd Division. The four of us came in together. It was dark when we got into Malmédy, but we could see some activity.

“I thought they would take us back, but they were on the move, so they could not afford to take us back. There were something like 75 who were killed right there. If I had been moaning, I would have been killed then.”

Paluch is one of the last five Malmédy Massacre survivors left in the United States. The men who first heard about the massacre were from the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion.

The Only Organized Massacre at the Bulge

William “Stu” Getz said, “We [Company C, 291st Engineer Combat Battalion] were at a town called Malmédy. There was another outfit coming up, and our colonel told them not to go that way because the Germans were ahead of them. They said they could not disobey their orders. We heard a lot of gunfire for about 45 minutes, and two or three of the GIs came down from the massacre. They were wounded but survived, and we took them to the medics. Our colonel called up SHAEF to report what happened. We did not take too many prisoners after that.”

By December 20, Peiper’s command had murdered approximately 350 American prisoners of war and at least 100 unarmed Belgian civilians, this total derived from killings at 12 different locations along Peiper’s line of march.

So far as can be determined, the Peiper killings represent the only organized and directed murder of prisoners of war by either side during the Ardennes battle. The commander of the Sixth SS Panzer Army, Josef “Sepp” Dietrich, said under oath during the war crimes trials of 1946 that, acting on Hitler’s orders, he issued a directive stating that the German troops should be preceded “by a wave of terror and fright and that no human inhibitions should be shown.”

Many of his troops certainly followed Dietrich’s orders—and earned lasting infamy.

Postwar Trial For the Malmédy Massacre

The postwar trial—Case Number 6-24 (United States vs. Valentin Bersin, et al.)—was one of the American-run Dachau Trials, which took place at the former Dachau concentration camp from May 16 to July 16, 1946. It is also an indisputable fact that the testimonies of the perpetrators of this war crime were extracted under duress before the ensuing trial. More than 70 people were tried and found guilty by the tribunal, and the court pronounced 43 death sentences (none of which, incidentally, were carried out) and 22 life sentences. Eight other men were sentenced to shorter prison sentences.

However, after the verdict, the way the court had functioned was disputed, first in Germany (by former Nazi officials who had regained some power due to anti-Communist positions with the occupation forces), then later in the United States (by Congressmen from heavily German-American areas of the Midwest). The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which was unable to make a decision.

The case then came under the scrutiny of a subcommittee of the U.S. Senate. A young senator from Wisconsin named Joseph McCarthy used it as an opportunity to raise his political profile, coming to the defense of the convicted men by stating that the court had not given them a fair trial. This drew attention to the trial and some of the judicial irregularities that had occurred during the interrogations preceding the trial itself.

However, even before the Senate took an interest in this case, most of the death sentences had already been commuted due to a revision of the trial carried out by the U.S. Army. The other life sentences were commuted within the next few years. All the convicted war criminals were released during the 1950s, the last one to leave prison being the infamous Joachim Peiper in December 1956.

Manfred Thorn, a veteran of the 1st SS Division, Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, wrote a book and released a DVD titled Mythos Malmédy in which he claims that the massacre never occurred.

After much searching, co-author Martin King located Thorn in Nuremberg. King said, “His wife, Hazel, a British woman, answered. She seemed to be a very mild-mannered and approachable woman, so I asked if I could speak to Mr. Thorn. I asked him his opinion, which he was quite reluctant to impart when I told him that I was in the process of writing a book with a friend in the United States. He said quite sternly, ‘The Malmédy Massacre was a setup; it never happened. Those bodies were placed there by U.S. intelligence to appear like they were all massacred. That is the end of it. I don’t want to participate further; respect my decision.’ So ended our discussion.

“Some days later, I visited the U.S. cemetery in Neuville-en-Condroz. This cemetery had been the location of the mortuary after the Battle of the Bulge. The bodies of the victims had been brought there for forensic examination and identification. It was more than apparent that many of the victims had been shot at close range due to the nature of the bullet holes in their skulls. Moreover, there’s pretty compelling evidence to suggest the 1st SS Division was more than capable of completely ignoring the Geneva Convention rules.”

The End of the Battle of the Bulge

The German counteroffensive was finally stopped at the end of January 1945—many miles short of its objective of Antwerp, Belgium. Despite inflicting heavy casualties on U.S. forces, it had failed to achieve its aims; the Americans and British did not fall out with one another, nor did they join with the Germans in turning against the Soviets. With many of its best troops, tanks, and artillery pieces now gone, Germany now had no hope of winning the war.

The complete story is captured in the authors’ book, Voices of the Bulge (Zenith Press, 2011), from which this article is excerpted.

It’s always madding when the command structure ignores reports of buildups reported by enlisted personnel. You would think that through the centuries they would learn the little guy on the ground knows what is going on.