By Herb Kugel

In 1941-1942, British journalist Alistair Cooke traveled through the United States. In his description of his trip, American Home Front 1941-1942, he reported stopping for breakfast at a restaurant in West Virginia where, “the sugar was rationed at breakfast, and there was a note on the menu requesting that … in the interests of ‘national defense,’ keep to one cup of coffee.”

Rationing struck the American public in 1942. It arrived with force and uncertainty and generated an economic crisis that could have caused America to lose the war. It came originally on August 28, 1941, without the approval of the United States Congress. The Office of Price Administration (OPA), which administered rationing during World War II, was established within the Office for Emergency Management by President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8875.

Office of Price Administration: “Born in Strife and Lived in Turmoil”

The OPA’s initial function was to stabilize prices (price control) and rents as the U.S. government readied for America’s certain involvement in World War II. From this beginning, the OPA’s economic power soon grew mighty.

The OPA became an independent agency under the Emergency Price Control Act, a law passed by Congress and signed by President Franklin Roosevelt on January 30, 1942. The organization was given the authority to place ceilings on all prices except agricultural commodities. It could ration virtually everything else, including tires, gasoline, and new automobiles, as well as such consumer items as sugar, coffee, shoes, silk stockings, meats, perfumes, and processed foods.

The OPA didn’t wait to exercise the power it knew it would be handed. Richard Lingeman reports in Don’t You Know There’s a War On? The American Home Front 1941-1945, that the OPA “got itself into the rationing business by ordering, on its own initiative, a tire-rationing plan.” The program went into effect on December 30, 1941, and was fully active in January.

The American Historical Society records that 8,000 rationing boards were created to oversee the tire-rationing program as well as the many other restrictions the OPA knew would soon follow. Lingeman reported, “More than 30,000 volunteers were recruited to handle the vast paper work involved in controlling prices on 90 percent of the goods sold in more than 600,000 retail stores and issuing a series of rationing books to every man, woman and child in the United States. As the war drew on, nearly every item Americans ate, wore, used or lived in was rationed or otherwise regulated.”

Stephen W. Sears reported in the October/ November 1979 issue of American Heritage, “In size the OPA was second only to the Post Office Department; in bureaucratic complexity it was unmatched. It was, said one observer, ‘born in strife and lived in turmoil.’”

Rationing Rubber

The strife and turmoil commenced even before the OPA was formally activated. It began with a rubber crisis but rapidly expanded outward into gasoline. Whether the OPA had been legal in acting on its own in regard to tire rationing, the fact remained the government desperately needed tire rationing to begin at once. Just 660,000 tons of crude rubber had been stockpiled as opposed to an annual U.S. consumption of between 600,000 and 700,000 tons; the War Department saw its rubber stockpile rapidly vanishing.

Japan’s seizure of vast rubber plantations during its conquests in the Malay Peninsula (southwest Thailand, western Malaysia, and the island of Singapore) and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) in early 1942 made the situation even more critical by cutting the sources to nearly 90 percent of America’s natural rubber supply.

After the OPA clamped down on the sale of tires, it followed with a ban on tire recapping and a shocked American motoring public of some 30 million drivers was slammed with an initial taste of what life under rationing would be like. Few drivers were allowed to obtain certificates to purchase new tires, and anyone who owned more than five tires was ordered to turn over the “extras” to his or her local gas station. While some drivers complied, others did not, and still others paid exorbitant prices for tires, doing this without concern about the government’s regulations or where the tires came from.

Even with the shortage, not every driver experienced difficulty in getting new tires in early 1942. Cooke reported on a unique tire contest he had observed: “[Getting tires] … was child’s play for a couple of ex-gangsters of my acquaintance (they bought their phonograph records where I bought mine) who, immediately after the order freezing rubber had gone out, started a snobbish game of seeing who could most frequently drive out in the morning with a new set of white-walled tires.”

Restrictions of the sale of new cars came next. This began on January 1, 1942, when a freezing order banning the sale of all new cars went into effect until a rationing program could be worked out. This program was to be made public by January 15, but that date was quickly pushed back to an unspecified date in February. However, on January 14, 1942, the government ordered the stockpiling of all cars shipped after January 15. Cars shipped to dealers could not be sold until specific permission was granted—if this permission was deemed “in the public interest.” The January 14 stockpiling order was followed a month later with a government order that placed all new cars in stock into long-term storage.

Gas Rationing and the Oil Crisis

Nevertheless, after these bold beginnings with tires and automobiles, the government began to shilly-shally about what it knew must come next. The next step—and it was critically important—had to be gas rationing, but Roosevelt was afraid to order it. Lingeman succinctly described a situation in which “the experts debated and the government from Roosevelt on down procrastinated about what measures to take beyond tire rationing….”

Various desperation-measure rubber-collection drives were tried, but the shortage remained critical while Roosevelt continued to hesitate even as work began on building synthetic-rubber plants. Finally, the president was forced into action. Gas rationing for the 17 states in the eastern United States was announced at the beginning of May; as might be expected, it set off a storm of opposition before going into effect on May 15, 1942. While the struggle over eastern states’ gas rationing continued unabated, the OPA went ahead with rationing and the issuing of ration books for the entire United States.

Gas rationing in the eastern states had not been ordered because of the rubber shortage but because of a fearsome and expanding oil crisis. On paper, America’s oil future had looked secure as far as supplies were concerned. Stephen Sears recorded that “the United States was entirely self-sufficient in oil, and indeed was a major exporter of petroleum products. At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, North America accounted for 64 percent of the world’s crude-oil production. (The Near and Middle East’s share, by contrast, was a mere 5.7 percent.)”

Sears then reported the view of Dr. Robert E. Wilson, a Standard Oil Company of Indiana executive and a government consultant on oil production. Wilson had stated that the outlook for the American petroleum industry was very positive, so much so that “even satisfying the enormous demands of a mechanized army presents no serious problems.”

Dr. Wilson was wrong. There were “serious problems” and the outlook was grim. Wilson had omitted both the transportation of oil and German submarines from his thinking. Before the war, the eastern oil refineries depended on tanker delivery for 95 percent of their oil; many tankers sailed along the Gulf Coast from ports in Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana and then up the East Coast to their various destinations. However, with the start of the war, German submarines, operating alone or in wolf packs, began sinking a great many American or American-leased tankers sailing this route.

Cooke reported a conversation with a Texan, a man who operated a small fleet of tankers that sailed along the Gulf Coast then up the East Coast to New Jersey. The man confessed that he was a constant insomniac since the war began, “waking with a start and wondering how many boats I lost last night.” When asked how many boats he ran, the Texan replied sadly, ‘Well I have twelve. [At least] this morning I had twelve. By the time I get to New Orleans … I’ll have eight or nine maybe. I had twenty, three months ago.’ ”

The government solution was to link the rich Texas oil fields with the northeastern states through the construction of the Big Inch—a 24-inch pipeline beginning at Longview, Texas, and eventually extending to various refineries throughout the eastern United States. Gas rationing was urgently needed because the first stage of the Big Inch was not scheduled to be completed for another year. In spite of an obviously desperate situation, gas rationing was met by powerful protests from within Roosevelt’s cabinet as well as by outrage from the big oil interests when they heard details of the rationing plan. The government limited motorists to between 2.5 and five gallons of gasoline per week.

The Critics of Gas Rationing

Harold L. Ickes, Roosevelt’s secretary of the interior as well as his petroleum coordinator, slammed the rationing plan as “half-baked, ill-advised and hit or miss.” Many oil executives claimed East Coast gas rationing did nothing more than set the stage for future nationwide rationing. Powerful oil interests organized a propaganda campaign against East Coast rationing and on the May 10 weekend, the last weekend before rationing went into effect, over 200 members of Congress asked for and received X cards, which allowed the bearer unlimited purchase of gasoline.

However, for senior American planners, the issue was not only corporate greed, although that was bad enough. The main issue was America’s economic and military survival. Would America’s drivers have enough gasoline to go to and from work and, if not, what would this do to them, the economy, and the war effort? The situation was a government nightmare.

Sears stated: “All across the country new arms factories were springing up … far from public transportation. This was particularly true in California, center of the burgeoning aircraft industry. Seven out of ten war workers in the Los Angeles area depended on their automobiles to get to work; at some plants the ratio was as high as nine out of ten…. Investigators at two hundred key industrial sites in fourteen states found 69 percent of the employees had no alternative to commuting by car.”

It became obvious that the private automobile was absolutely critical to the war effort, but still Roosevelt continued to vacillate. Cooke attempted to explain the American public’s deep concern over gas rationing to often extremely unsympathetic British radio audiences: “But consider that everywhere west of the Mississippi, cities were built on the assumption that the only way a human moved was by motor car.” He then reported a conversation with a Wyoming sheep rancher, who, commenting on the government’s request for motorists to share their cars with their neighbors, said forlornly, ‘My neighbor lives 97 miles away.’ ”

The government discovered a painful truth as many people in the eastern United States seethed in anger and did their best to break the gas rationing rules. If rationing was to work, the same rules would have to be applied equally all across the country.

The OPA’s Four Ration Books

However, as May 1942, ended with Roosevelt still waffling over nationwide gas rationing, the OPA had frozen or was readying to freeze the prices on practically everything. Virtually all consumer goods were either rationed or soon would be. Sugar would be rationed first and coffee would soon follow.

In her article about rationing, Mary Brandeberry described what happened with the first item rationed, sugar: “Individuals were required to go to local grade schools, where volunteers and teachers interviewed them, checked on the size of the family and how much sugar that they had at home. Then, based on what the rationing board heard, the individual was issued a ration book with a year’s worth of stamps.”

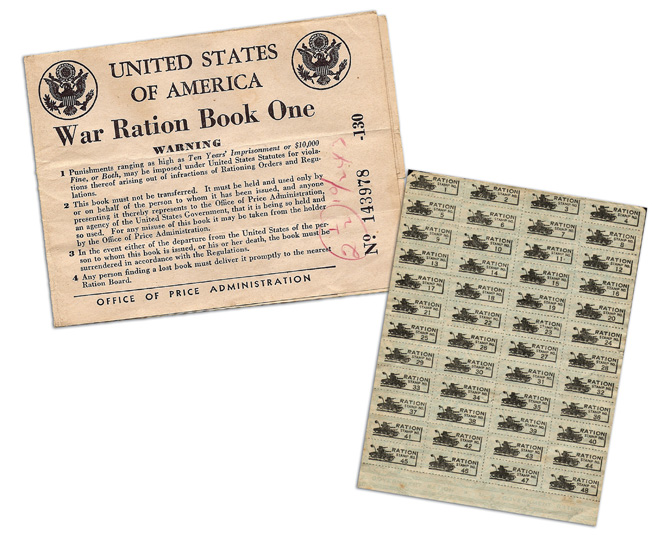

The plan had obvious flaws, the most obvious being that many board members knew the applicants personally, and some were even relatives. However, even with this, rationing soldiered on. The OPA had originally planned to issue five ration books but finally issued only four. The first page of the first book displayed warnings that violating the rationing rules and regulations could result in fines of up to $10,000 and 10 years of imprisonment. This was followed by a series of rules. The rationing book could only be used by the person to whom it was issued and if that person left the country or died, the book had to be surrendered back to the government. Any book found had to be returned to the OPA.

Brandeberry continued her description of the first rationing book: “Page two and three was actually the Certificate of Register. This certificate contained vital information such as the name and address of the individual, and his or her physical description such as height, weight, eye and hair coloring, sex, and age. The bottom of the certificate contained numbered stamps towards sugar, and later coffee. The last page of the book shows the signature of the person that the book belonged to.”

More Money, Fewer Consumer Products

The rationing system itself was fraught with difficulties, and the rules changed as the system went along. The rationing coupons themselves almost became a second monetary system, as the following from the University of Massachusetts Digital Collection illustrates: “Ration book four also introduced red and blue cardboard tokens, each valued at one-point, to be used as change for ration coupon purchases…. For example, if a can of corn was listed at 7 ration points, and the purchaser had only a 10-point stamp left for the week … [the purchaser] would lose three ration points as part of the purchase. When tokens came into use, the purchaser could receive three tokens, each worth one point, in exchange. An advantage of tokens was that they never expired, while the stamps did. Ration book four also included ‘spare’ stamps that were occasionally validated for the purchase of five extra pounds of pork.”

While rationing struggled along, more and more American workers were earning more and more money as defense and defense-related industries geared up for the massive war effort. However, there was less and less on which these workers could spend their money as meat, clothing, and other items became rationed and as quotas were set for their production.

More and more dollars began competing for fewer and fewer new consumer goods as more production was shifted away from the civilian market and into the war effort. New radios, refrigerators, and stoves started to vanish from stores as tanks and airplanes began to roll from assembly lines. The rationing rules became comprehensive.

Vetoing the “Rubber Czar”

The government seemed on track except in the most critical area, gasoline. As summer arrived, even though the need was growing more desperate by the hour, the government had yet to define a nationwide gas-rationing policy. Roosevelt was in trouble and he knew it, but luckily he was handed a way out when Congress decided to “go it alone” and passed Iowa Senator Guy M. Gillette’s bill to establish a “Rubber Czar” whose job would be to head a special organization that would be independent of the War Production Board. This civilian agency would be charged with overseeing and coordinating the war economy.

The bill creating the czar had been shoved through Congress by the farm bloc and its real purpose was to force synthetic rubber to be made only from agricultural and forest products. Roosevelt knew that he could not let this bill become law—he could not allow two organizations, one frankly biased toward the farm bloc, to struggle against each other with America’s war economy as the prize.

He knew he must stop this bill from becoming law or risk critical damage to America’s war production machinery; thus he vetoed the bill, but did it in a way that rather elegantly got him off the hook. In his veto message he announced the formation of a completely reliable and impartial fact-finding commission to thoroughly examine rubber, oil, and gasoline rationing in great detail. Sears noted that Roosevelt, “in one neat maneuver, had side-stepped, gotten out from under, and passed the buck” on gas rationing. Nevertheless, Roosevelt desperately needed a man who had unquestionably earned the nation’s complete trust and respect to run this committee.

Bernard Baruch: The “Park Bech Statesman”

Fortunately for both Roosevelt and America, there was such a man. He was Bernard Baruch, the 72-year-old “Park Bench Statesman,” the wealthy “Wall Street Whiz” who had been a presidential adviser, first to Woodrow Wilson during World War I, and then, between the two world wars, to Presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover. Now, he would advise Roosevelt (and Truman after the war). In an article, “Three Men on a Bench,” in Time, August 17, 1942, Baruch is described as a man with a “white-topped frame … long legs and [wearing] the inevitable high black shoes.” Baruch liked to confer with officials on a bench in Washington’s Lafayette Park because the park provided privacy and a relaxed atmosphere, thus he became known as the “Park Bench Statesman.” The “Three Men” in the article’s title referred to Baruch and his two fellow committeemen, James Bryant Conant, the president of Harvard University, and Karl Taylor Compton, president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The report Baruch and his two associates issued to Roosevelt was blunt and frightening. In a September 21, 1942, Time article, “Outline of the Future,” the staff writer quotes parts of the Baruch committee’s report to the president: “We find the existing situation to be so dangerous that unless corrective measures are taken immediately this country will face both military and civilian collapse. The naked facts present a warning that dare not be ignored. If they are, the U.S. will have no rubber in the fourth quarter of 1943 to equip a modern mechanized army.”

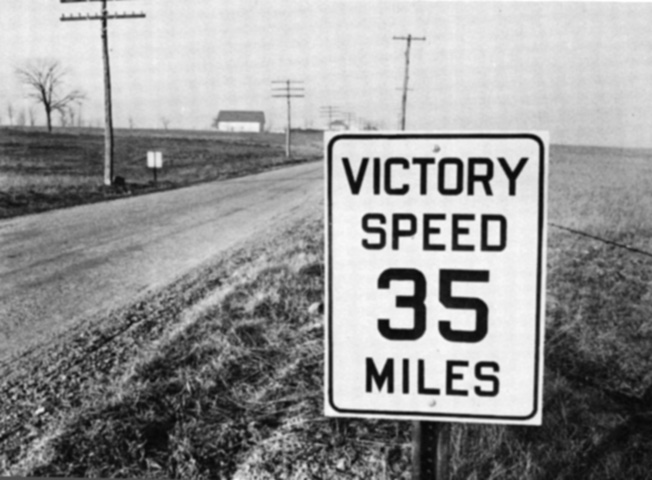

In no uncertain terms, Roosevelt was warned that America could lose the war if he took no action and continued to allow various pressure groups to continue unchecked in their greed and total self-interest. Roosevelt got the message: He ordered full gas rationing to begin on December 1, 1942. He also ordered a ban on pleasure driving, as well as a 35-mile-per-hour speed limit on all of America’s highways.

Rationing had already stomped into the American way of life. For example, when it came out, the 1943 Sears, Roebuck and Company catalogue already contained a complete list of rationed farm equipment. Planting, seeding, and fertilizing machinery were listed, as were tractors, and dairy farm machinery and equipment. There was even a section in the catalogue titled “If you are a farmer or poultry raiser and want to buy a hand pump” and, conversely, a section on, “If you are not a farm or poultry raiser and want to buy a pump or other farm equipment.”

In this, as with other items, the rulings of the OPA were all-powerful though they were very often furiously appealed. Nevertheless, the bottom line for the nation as a whole was that the “Park Bench Statesman” had pushed Roosevelt into finally taking the action he knew he had to take.

In the government’s gas-rationing rules, individual driver gasoline rationing quotas determined an A, B, or C sticker that was required to be displayed on the bottom left corner of the windshield. In effect, it was a sticker that defined a driver hierarchy. An A-sticker driver was assumed to do no “essential” driving. The driver who received this sticker was given the lowest gas allocation: four, and then later three, gallons per week. Since the government estimated 15 miles to the gallon, an A-sticker holder was limited to 60 miles of driving per week. Many drivers, frustrated with the restrictions, simply put their cars up on blocks, drained the oil from their engines, removed the batteries, and covered the vehicles with tarps “for the duration.”

The B-sticker holder had some essential driving to do and received a supplementary allowance based on that need. The C-sticker driver also needed the car for essential driving (such as a physician making house calls) but was allocated all the gasoline needed. There was also a T-sticker for truck drivers, who also could get all the gas they needed. Taxi drivers and farmers had their own stickers.

Gas rationing quickly faced serious difficulties because the government did not take into account the personalities of many American drivers—personalities that expressed themselves through a mass influx of A-sticker drivers flocking to their local rationing boards with the most absurd reasons for demanding that their A-stickers be upgraded to B- or C-stickers. The gas ration sticker somehow had become a status symbol and many drivers argued furiously to have their A-sticker upgraded.

Crime and the Black Market

Crime was also a serious problem throughout the nation at that time. Ration books and stamps were regularly stolen, even from OPA offices. Counterfeiting grew into a real problem as both ration books and stamps were regularly forged. Some of this forging was of excellent quality as “top professionals” expanded their efforts from the counterfeiting of money to the excellent counterfeiting of ration books and stamps.

A significant black market was another problem, with, for the most part, the black marketers selling meat, sugar, and gasoline. The demand for black-market gasoline was significant enough to cause armed criminals to attempt to hijack trucks on solitary roads; many drivers started carrying guns.

Successes and Failures of Rationing

Yet, in spite of all its difficulties, did rationing work? Lingeman stated that “rationing was the most concerted attack on wartime inflation and scarcity, and by and large it worked.”

One way to examine the success or failure of rationing in this “concerted attack” was to consider the U.S. Government Consumer Price Index (CPI) calculations during the war. CPI is an inflationary pointer that measures the change in the cost of a fixed basket of products and services, including housing, electricity, food, and transportation. The CPI is also called the Cost-of-Living Indicator and for America’s war years––1942, 1943, 1944, and 1945––the figures were:

$1.00 in 1942 had the same buying power as $1.06 in 1943.

$1.00 in 1943 had the same buying power as $1.02 in 1944.

$1.00 in 1944 had the same buying power as $1.02 in 1945.

Using 1942 as a base year, inflation ran at six percent in 1943, and then remained lower and constant at two percent in 1944 and 1945.

Although the rationing system was widely hated and often abused, it worked. The massive American military machine rarely lacked for any essential item.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments