By Blaine Taylor

By June 1, 1943, British actor Leslie Howard, 50, was one of the most famous actors in the world, one of the leading male stars of one the greatest box-office draw movies of all time, the 1939 blockbuster Gone with the Wind.

A Hungarian Jew in Hollywood

Born of Hungarian Jewish immigrants as Leslie Howard Stainer in London in 1893, Howard had served as a junior officer in World War I until he was mustered out of military service in 1916 after suffering shell shock in the trenches of France.

Becoming an actor as therapy on the advice of his doctor, Howard made his stage debut in 1917, and later earned Academy Award nominations for both the 1933 film Berkeley Square and the 1938 movie Pygmalion. But it was as the star-crossed Confederate lover Ashley Wilkes that he remains best known to this day. His acting career, however, would soon come to a tragic end.

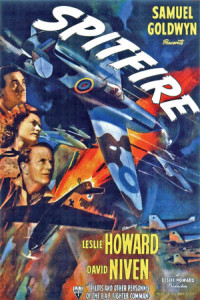

In 1940, he left Hollywood and returned to England where he hoped he might be able to do something to help Britain’s war effort. In 1941 and 1942 he starred in several war films including 49th Parallel (1941), Pimpernel Smith (1941), and The First of the Few (called Spitfire in the United States; 1942), the latter two of which he also directed and co-produced.

Leslie Howard’s Flight to Lisbon

In April 1943, Howard flew into neutral Lisbon, Portugal, ostensibly to present a series of lectures on his films and on the role of Hamlet, as well as to look after his own film-distribution business affairs on the Iberian Peninsula. However, other reports said that he was in Lisbon for another reason––to rally support for the anti-Fascist cause. As he prepared to fly out of London, however, he told his wife Ruth that he had “a queer feeling about this whole trip, but–what the hell!–you know that I’m a fatalist anyway.”

One thing that may have planted the seed of apprehension in his mind was the fact that on April 19, just two weeks earlier, this very same plane in which he was to ride—Ibis—a DC-3 plane operated by the Royal Dutch Airlines, had been oddly and unexpectedly attacked by a flight of from six to eight deadly German Luftwaffe Junkers Ju-88s off Spain’s Cape Corunna. The plane had even taken some hits before escaping to safety in a cloudbank and then continuing on to Portugal.

Airport officials were mystified, since both the British BOAC aerial service and the Royal Dutch Airlines had flown entirely undisturbed despite the ongoing air war over the Mediterranean, and at least 5,000 passengers had taken off and landed safely. Until the spring of 1943, there had been a sort of gentlemen’s agreement between the capitals of Lisbon and London to continue the daily flight without hindrance. Thus, despite the freak attack of April 19, the daily flights between Portugal and the United Kingdom resumed.

Until June 1, 1943, the Germans had left the Lisbon-to-Free World flights alone, as many of their passengers were useful to the Axis war effort, but that day’s Flight 777 to London was about to be proven the exception.

A Case of Mistaken Identity

With his visit concluded, Howard and a dozen or so other passengers boarded the Ibis at Lisbon’s Portella airport at 9:35 am on June 1, 1943, for what was expected to be a routine return flight to London.

A nervous Leslie Howard boarded the flight with Arthur Tregear Chenhall, a heavy-set friend and business associate of the famous actor, who somewhat resembled Winston Churchill and who also enjoyed smoking large cigars. (A persistent rumor during and after the war—fueled by the prime minister himself—had it that German agents in Lisbon mistakenly thought Chenhall was Churchill, and thus had planned to target him.)

Did Howard have reason to feel unsafe? Maybe so. Having previously played the roles of Professor Henry Higgins in Pygmalian, Romeo to actress Norma Shearer’s Juliet, and Philip Carey in Of Human Bondage, Howard was also known for his famed 1934 role in The Scarlet Pimpernel opposite Merle Oberon. Therein he portrayed an English nobleman secretly helping condemned French aristocrats escape the blade of the guillotine and constantly thwarting his rival, a diabolical secret policeman of Revolutionary France.

To aid the Allied war effort and defeat the hated Nazis, Howard reprised this role in the 1941 film, Pimpernel Smith, which was updated to replace French Revolutionaries with the Nazis of the Third Reich as the villains. The actor played Horatio Smith, an archaeology professor traveling in Europe who rescues refugees from the German Gestapo (Secret Police).

According to author Jerrold M. Packard in his excellent 1992 study—Neither Friend Nor Foe: The European Neutrals in World War II—“[German] Propaganda Minister Dr. Joseph Goebbels had seen Howard’s 1941 film Pimpernel Smith … [and] decided to get the man who not only starred in this attack on the Reich, but who directed and produced it as well.”

Packard noted, “When passing Germans in the lobby of the Ritz … the actor made gentlemanly efforts to conceal his own contempt. He wasn’t aware, of course, that among these Germans were agents reporting his movements back to Berlin.”

Other passengers on Flight 777 included Reuters News Service reporter Kenneth Stonehouse; Wilfred Israel, a Jewish relief activist; mining engineer Ivan Sharp, who had been negotiating important tungsten imports for England; Shell Oil Company’s Lisbon manager, Tyrrel Shervington; and two other men, a trio of women, and two or three children.

“I Feel Bad About This Air Trip”

Oddly, the only reason that both Howard and Chenhall were able to find seats aboard was because the airline had “bumped” at the last minute two other would-be passengers: nanny Dora Rowe and Derek Partridge, the young son of a Foreign Office official, to make room for the famous actor and his aide.

Another who missed the fatal flight was Roman Catholic English College Vice President Father A.S. Holmes. Waiting in the terminal, Father Holmes received a hasty message to call either the British Embassy or the papal nunciature right away. Because the aircraft wouldn’t wait for him, the priest watched it take off from the terminal.

Afterward, strangely, no one at the telephone switchboard could verify having received a call for the priest, and both the embassy and the papal office denied making any such request for him to contact them. His last-minute removal from the doomed aircraft thus remains a mystery, one of several.

Later, in the wake of what happened, it developed that there had been more odd occurrences before the flight. Shervington had dreamed that the plane had been shot down and that he’d gone down with it, and Stonehouse moaned to a friend before taking off, “I’m not normally frightened, but somehow, I feel bad about this air trip. I wish that I could go to sleep here and wake up at some English airfield.”

Were these just the usual “fear of flying” jitters shared by many passengers before and since? Again, maybe not, as it later developed that Berlin not only perceived Howard as an outright wartime Allied propagandist, but also, perhaps, as more than that: as an intelligence agent. The Nazis also viewed Shervington as a fellow spy, and Zionist activist Wilfried Israel as an avowed enemy of Third Reich.

Indeed, as the passengers boarded the flight, they were even watched by the crew of a nearby Lufthansa German civilian airliner.

Flight 777 Falls From the Sky

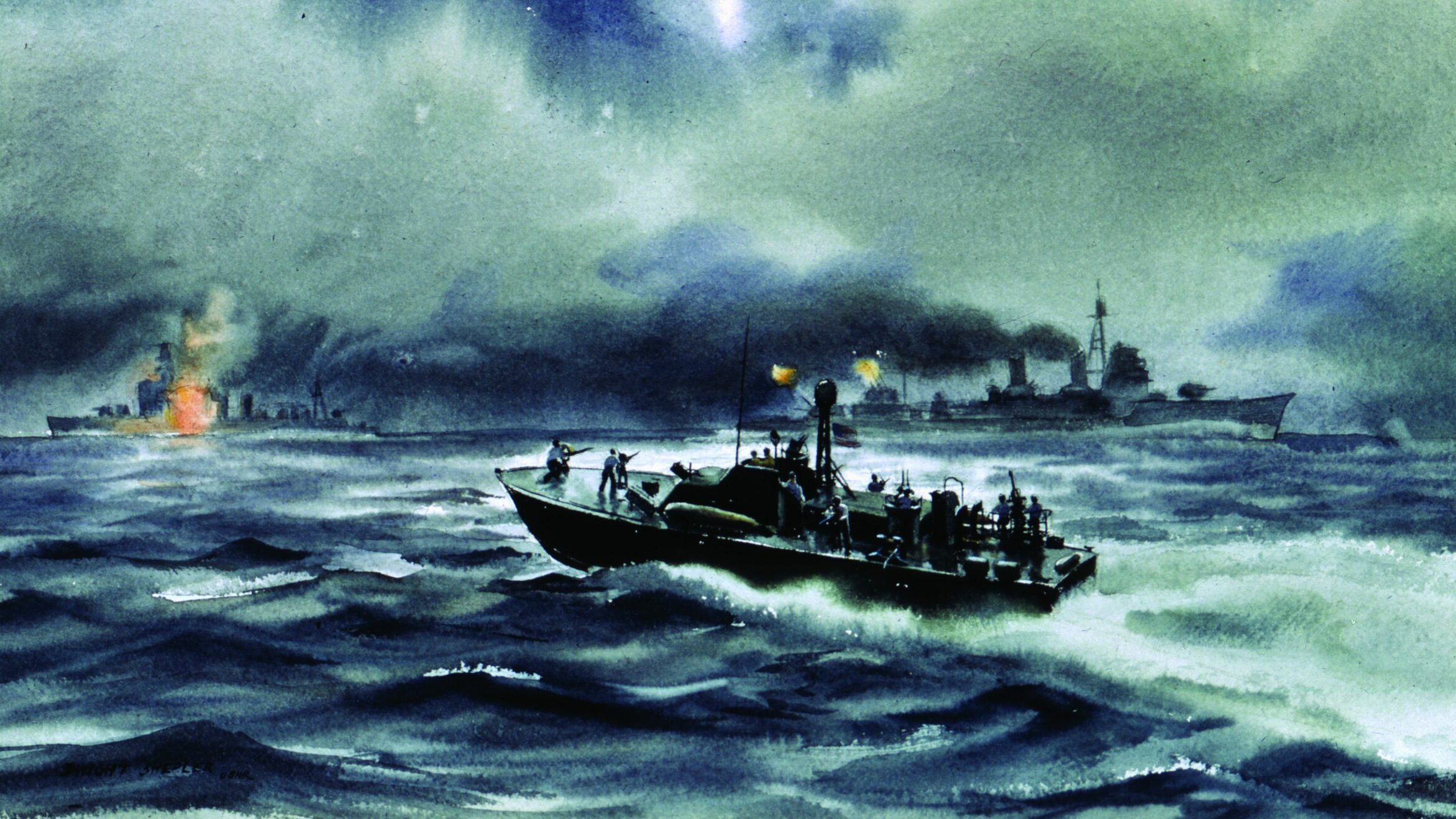

The ill-fated Ibis took off and soon reached an altitude of 9,000 feet, setting a course for a landfall at Spain’s Cape Villano before flying out over the Bay of Biscay for the seven-hour flight to Bristol, England. Unknown to the passengers and crew of the Ibis, as they passed Cape Villano, a powerful German omnidirectional radio navigation beam locked on to the Dutch aircraft.

Another fact unknown to the doomed passengers and crew aboard Ibis was that, as it took off from Lisbon, a squadron of eight German Junkers Ju-88 crews were also preparing to take off from their Luftwaffe base in German-occupied France near the port city of Bordeaux for a patrol over the Bay of Biscay. Its exact orders were never made known, and it is doubtful that these deadly Ju-88 fighter-bombers were on either air-sea rescue or U-boat protection missions.

What is known, however, is that the Ibis and the flight of eight Ju-88s were now flying on intersecting paths. Shortly before 1:00 pm on that clear June day, Flight 777 suddenly was raked by bursts of cannon fire and machine-gun bullets from the attacking Ju-88s over the water some 200 miles northwest of A Coruña, Spain. The DC-3’s wireless operator quickly tapped out a chilling message in Morse code: “From G-AGBB [Ibis’s call sign] … I am followed by unidentified aircraft … I am attacked by enemy aircraft.” After that, the transmission went dead.

As during the April 19 assault, the DC-3 again tried unsuccessfully to reach the safety of the clouds, but instead headed for the sea below, trailing a stream of flames. It slammed into the water with great force, killing all on board. After the airliner crashed, the attacking planes photographed bits of smoking wreckage floating on the rough seas and then returned to their home base.

“The Inscrutable Workings of Fate”

Three days after the incident, the New York Times reported, “It was believed in London that the Nazi raider[s] had attacked on the outside chance that Prime Minister Winston Churchill might be among the passengers.”

Both the British and Portuguese air authorities were shocked when it became known that an armed belligerent had apparently shot down an unarmed, clearly marked civilian airliner in broad daylight. So sure had they been that such an event would never happen—and that the earlier attack of April 19 had been but an accidental aberration—that they had summarily refused to extend the air routes farther out over the Atlantic Ocean as a defensive measure. Nor had they rescheduled the flights to the hours of darkness.

When the Allies’ secret Nazi code-breaking capabilities known as Ultra were finally made public decades after World War II ended, it was learned that the British had known in advance of possible German plans to shoot down Flight 777 based on their assumption that Churchill was aboard. To avoid compromising the Ultra secret, the British could not pass on this bit of intelligence to the airline.

In his monumental history of the war, Churchill kept alive the mistaken-identity thesis, and referred to Leslie Howard’s death as one of “the inscrutable workings of fate.” (Read about these and other lesser-known events during the Second World War inside WWII History magazine.)

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments