By James Verini

Crowded in front of the television in Eli Rosenbaum’s office, his staff was taken with a giddy anticipation not often found in employees of the United States Department of Justice.

The mood was doubly odd because the footage they watched was pretty dull: a Gulfstream jet idled on a runway at Cleveland International Airport. Rosenbaum’s eyes were glued to the screen too, but he wasn’t giddy. He wore a skeptical frown. The coverage was broadcasting live on CNN, on May 11 of 2009, and yet Rosenbaum didn’t believe the plane on the screen would lift off.

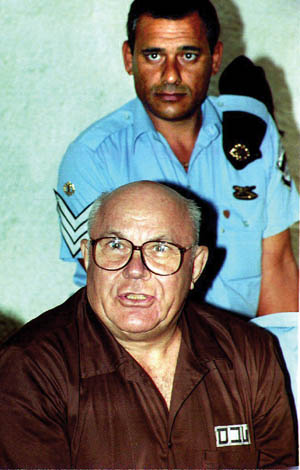

The director and chief prosecutor of the Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations—the “Nazi-hunters” in local parlance—he had been waiting for most of his adult life to watch this particular flight and its 90-year-old passenger, John Demjanjuk, depart the United States for good. After a morbid odyssey of hearings and appeals, injunctions and stays, exonerations and recriminations, however, no disappointment would surprise him.

Maybe the engines would shut down, Rosenbaum mused. Maybe the attorney general would call him with an 11th-hour reprieve? Maybe Demjanjuk, who was lying on an ambulance gurney in the plane’s cabin, the only passenger who’d not be making the return trip from Germany—maybe he would have a heart attack. Or charge the cockpit—for all his claims of decrepitude, the Ukrainian-born Demjanjuk was still a physically menacing man, with hulking shoulders, a head like a cannon ball, and behind outsized bifocals a glower that only seemed to corroborate the charges against him––that he committed mass murder while he was a concentration camp guard serving in the Schutzstaffel, or SS, in Nazi-occupied Poland.

“This was the case in which anything that could have gone wrong had gone wrong,” Rosenbaum recalls thinking, as he sat there in his office at 7:30 in the evening—he remembers the time exactly—watching the plane stalled on the tarmac. “Something’s going to stop it. It isn’t going to leave.”

OSI: The Most Successful Nazi-Hunting Organization in the World

The case of Demjanjuk stretches so far back it precedes the existence of OSI, which was set up, 31 years ago, with one mandate: to track down former Nazis and collaborators who had immigrated to the United States without––or, more troublingly, with––Washington’s knowledge, and to try to deport them.

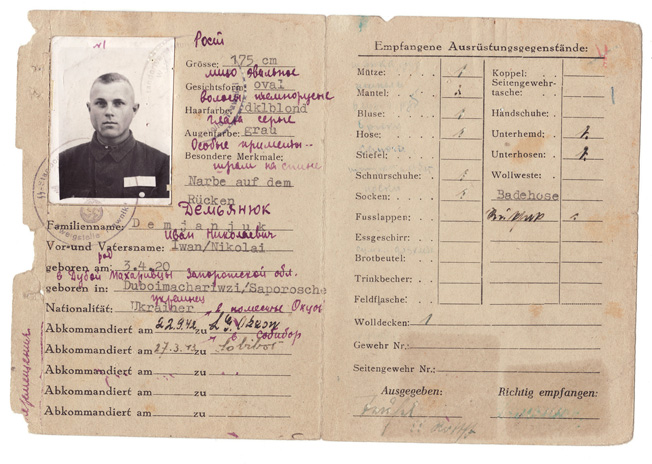

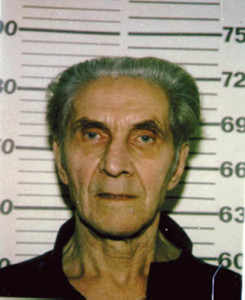

A retired Ford engine mechanic and grandfather from the Cleveland suburb of Seven Hills, Ohio, Demjanjuk first came to the attention of the government when his SS I.D. card was accidentally recognized in a photo spread by survivors of the Treblinka concentration camp. Since then he had been convicted by an American court, in 1987, of entering the country illegally; extradited to Israel, where he was convicted on flimsy evidence that he was a notorious guard, known as Ivan the Terrible, at Treblinka, and sentenced to be hanged; exonerated by the same court, then sent back to the United States, where, in 2002, he was again tried and again found guilty of the original charges of having served at a series of camps (though not Treblinka), and again denaturalized; and finally deported, in May, to Germany.

The plane did indeed take off, after an hour on the runway. Demjanjuk now lives in a cell in Stadelheim prison, a young Adolf Hitler’s home for a summer month, and spends his days in a Munich courtroom, facing charges of participating in the extermination of 27,900 people. The trial began in January 2010. His all but inevitable conviction may not come until this fall. That’s if Demjanjuk, who is usually wheeled into court on a gurney, does not die first. (As this issue went to press, there was still no verdict.) And while it’s true he was caught on camera in 2009 walking around and joking with ICE agents after claiming he was too ill to move, judging by his current appearance the latter possibility seems as likely as the former.

“Who would have thought at the end of World War II that 60-plus years later they’d still be prosecuting these cases?” Rosenbaum, who is 54, told me. “These are the ultimate cold cases. It’s hard enough to prove a mugging that took place down the street a week ago.” He said there are “a lot of misconceptions about this work, especially about how the investigations originate and how they’re conducted. There’s the Hollywood version of this. That just doesn’t happen.”

But in fact OSI is almost suspiciously cinematic. It has tracked down not just SS functionaries, but murderous police chiefs, fascist martinets, mobile kill-squad leaders, an aide to Adolph Eichmann, a pogrom-inciting propagandist priest, and a V-2 rocket scientist. It’s dug them up in Seven Hills and Long Beach, California, in Minneola, Long Island, and the south side of Chicago. OSI helped expose the Central Intelligence Agency’s sordid history with Klaus Barbie and the Nazi past of the late Austrian president and UN Secretary General Kurt Waldheim. It has identified Nazi-looted paintings––in the National Gallery in Washington. It’s now going after perpetrators from Rwanda and the Balkans.

And the Demjanjuk case, to name just one, has inspired a small library’s worth of government reports, op-ed rants, and legal digest articles, not to mention a good novel (Philip Roth’s Operation Shylock), a little-seen musical (The Trials of John Demjanjuk: A Holocaust Cabaret), and, indeed, a movie, Music Box, which was up for the Best Picture Oscar in 1989. The film has one particularly commendable aspect lost on most viewers––it accurately portrays the methodical nature of OSI investigations, which rely not on sensational revelations, nor Buenos Aires street-corner captures, but on archives and researchers, maps, translators, and historical minutiae. The stuff of war historians.

Each case is a years-long “needle-in-the-haystack” process, Rosenbaum said, and Demjanjuk’s case is not unique in its prolixity. OSI is by far the most successful Nazi-hunting organization in the world, having denaturalized, deported, or extradited 107 accused World War II war criminals from the United States thus far—a record neither the Simon Wiesenthal Center nor the Mossad approach—yet its work takes decades to complete. That’s when it’s completed at all: there are still any number of OSI defendants living in the United States who’ve had their citizenship stripped, but whom can’t be removed, because no country will accept them. Demjanjuk is the first OSI defendant Germany has ever agreed to try. Israel has refused to try any since it exonerated him.

An Organization Built Around Retribution

Music Box also features a hard-driving OSI chief who delivers this speech to the defendant’s daughter: “Do you really think I give a damn about punishing an old man? I don’t have any vengeance in my heart. But I’ll tell you what I do care about. I care about remembering. It’s too late to change what happened, but it’s never too late to remember what happened.” Which, significantly, is precisely the complaint that OSI’s critics make of it. Rosenbaum and his team are not as interested in the enforcement of law, they say, as they are in making a historical point—in retribution.

“There was the putrid smell of righteousness about the whole matter. Everybody was so eager to right the Holocaust,” said Gary Fleischmann, a defense attorney who represented Andrija Artukovi, whom OSI had extradited to the Soviet Union in 1987, where he was tried and convicted of treason and sentenced to death by firing squad. Artuković, a high-ranking official in Nazi-allied Croatia during the war and a leader of the brutal Ustaše, died while awaiting execution.

OSI was able to dig up copies of long-forgotten decrees Artuković had put his name to that persecuted Jews (for the sake, as one decree states, of the “protection of the Aryan blood and honor of the Croatian nation”). It found the decrees in a box in, of all places, the Library of Congress. Still, said Fleischmann, “There’s no question Artuković was an anti-Semite. But that’s not a war crime.”

Michael Tigar, a defense attorney and professor at Duke University School of Law who represented Demjanjuk, said, “I think an office which is set up around a particular issue and is staffed by people who become true believers represents a danger.” Tigar, unlike Rosenbaum known for his courtroom dramatics, quoted John Ruskin to me. “‘No more dangerous snare is set by the fiends for human frailty than the belief that our own enemies are also the enemies of God.’ When that snare takes hold of people they take the attitude they can do anything they want to win.”

“The Big Challenge For Me is to Build These Cases”

Unlike Tigar, though, most of the people whom Rosenbaum has faced in court would probably not say he’s willing to do anything to win. “Eli’s a decent guy, he’s a straight shooter,” Rad Artukovi, Andrija’s son, told me—in the same breath that he accused OSI of committing fraud in his father’s case, which was tried while Rosenbaum was not at OSI. Rosenbaum doesn’t revel in deporting senior citizens, and he doesn’t speak about his quarry with the contempt or trembling indignation that the subject of the Holocaust often elicits. He’s unfailingly solicitous and polite to defendants, OSI transcripts show, even when he believes them to be mass murderers.

“I’ve always been more of an investigative guy than a prosecutor,” Rosenbaum said. “In many respects what I like to do as a hobby at home is read my work.”

We were sitting, on an afternoon last November, in a conference room in OSI’s offices off New York Avenue in Washington, D.C. OSI consists of 11 attorneys, including Rosenbaum, four paralegals, and eight historians. Tall and trim, with small, intense blue eyes and a medium-thick mustache, Rosenbaum, a Long Island native, lives with his wife and two daughters in suburban Maryland. As we talked he sipped black coffee from a metal thermos and wore, hanging over a crisply pressed striped dress shirt, a DOJ I.D. card on a Yankees lanyard (the team was to face the Philadelphia Phillies in the first game of the World Series that night). On the walls by his desk hung, alongside a portrait of Babe Ruth, photos of Rosenbaum with Elie Wiesel, Bill Clinton, and Anne Frank’s protector, Miep Gies.

The office hallway walls, meanwhile, are adorned with black and white blow-ups of OSI defendants, with a section given over to a three-foot-wide rendering of Demjanjuk’s I.D. card from the SS training camp at Trawniki, Poland, still the central piece of documentary evidence against him. The same head and stare are there, but the young Demjanjuk looks perversely dashing, too. Near Rosenbaum in the conference room as we talked was mounted a more startling photograph, of Michael Kolnhofer, an alleged former camp guard who lived outside Kansas City. That is, until the day the photo was snapped in 1997.

It shows Kolnhofer propping open his screen door while opening fire with a pearl-handled Colt revolver upon police gathered outside his house. He really didn’t appreciate OSI’s investigation of him. He was shot by police on his doorstep, later dying of his wounds, a fate that echoed that of another OSI subject, Tsherim Soobzokov, who was killed after a pipe bomb was attached to his front door. Such episodes are rare, Rosenbaum emphasized. Most OSI defendants die natural deaths, often enough in the midst of litigation. “The big challenge for me is to build these cases. It’s what fascinates me the most,” he said.

The Holtzman Amendment

OSI was created by the so-called Holtzman Amendment, passed by Congress in 1978. Amazingly, this was the first time federal law specified in so many words that Nazis and their collaborators ought not reside here. Émigrés who arrived in the United States in the immediate postwar years came in under the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, which required little from applicants in the way of background information. Lying was routine. According to Allan Ryan, OSI’s director from 1980 to 1984 and the author of Quiet Neighbors: Prosecuting Nazi War Criminals in America, at least 10,000 World War II war criminals made it into the United States in those years. “I think it’s a conservative number. It may well be higher,” he said.

More amazingly, the government knew who some of them were. “While I was in Congress, someone came to me who was very familiar with the operation of the immigration service and told me the government had a list of Nazi war criminals living in the United States, and was doing nothing about it,” former New York Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman, author of the Amendment, told me. “There was a hearing with the immigration commissioner and I asked him: Is it true that you have a list of alleged Nazi war criminals living in the United States? And he said yes. I almost fell out of my chair.”

OSI began work the year after the Amendment passed. “The only way to make sure justice was done was to create a special unit with expertise and professional standing,” Holtzman said. “It’s going to go into the criminal division because they know how to get subpeonas and look for witnesses all over the world.” OSI does not prosecute war crimes; it shows that such crimes likely took place and made a defendant’s entry into America unlawful.

Eli Rosenbaum Becomes a Nazi Hunter

At the time, Rosenbaum was a student at Harvard Law School. A decade and a half after Adolph Eichmann’s execution in Israel, there was a resurgence of interest in the fate of Nazi war criminals. In 1977, Howard Blum’s breathless Wanted! The Search for Nazis in America was published. Rosenbaum read it and was “absolutely shocked,” he said. He would later find that much of what Blum reported was inaccurate, but no matter—he was hooked. He read in the Times one evening about the Holtzman Amendment, and, not wanting to waste any time, called the Justice Department switchboard—at midnight. “I thought, oh yes, this is the summer job for me,” said Rosenbaum, who was hired for an internship. (“It’s a summer job gone awry.”) After law school, Allan Ryan hired him as a full-time prosecutor. “Eli was one of the brightest, hardest working, most perceptive lawyers I’d ever worked with,” Ryan said.

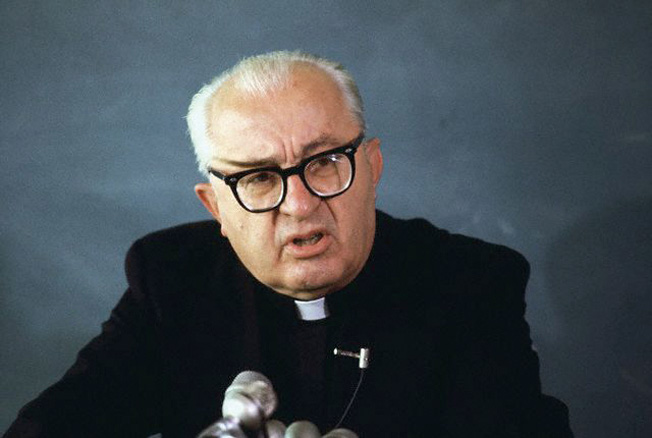

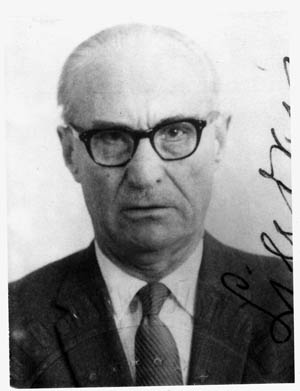

The office was understaffed and barely funded, and Rosenbaum was put to work straight away on the case of Archbishop Valerian Trifa, a leader of the Romanian fascists who’d moved to Detroit. The Justice Department believed Trifa had helped incite a murderous pogrom in Bucharest in 1941. Accounts of the episode are beyond imagining: according to a cable from the American ambassador, the fascists firebombed synagogues and hung Jews from meat-hooks, their throats slit, in travesty of kosher traditions, while at least 60 Jews were skinned, while alive, including a five year-old girl. When OSI caught up with him, Trifa was passing his middle age as the highest ranking Romanian Orthodox cleric in North America.

In 1955 he led a convocation prayer at the U.S. Senate, and avoided prosecution for almost four decades in part by being an informant for the FBI. So apparently grateful was he to J. Edgar Hoover—whose interest in chasing communists far surpassed any concern that fascists had emigrated en masse to the States—that in 1963, when it looked as though John F. Kennedy might retire the FBI chief, Trifa wrote to the president personally, declaring “the American people need men like J. Edgar Hoover.”

In one of the investigation’s most astounding developments, OSI lifted a latent fingerprint of Trifa’s (with the help of a contrite FBI) from a postcard he’d written to Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. To this day, it is the oldest latent fingerprint ever detected by the Bureau. After Israel declined to try him, Trifa decamped to Portugal in 1984, though not before he told an interviewer that “all this talk by the Jews about the Holocaust is going to backfire.”

Rosenbaum’s First Breakthrough

It was thanks to another book Rosenbaum read, this one requiring no exclamation points in the title, that he built his own first breakthrough case. In a Cambridge used bookstore where Rosenbaum liked to browse, he happened upon French survivor Jean Michel’s harrowing memoir Dora, about his time at Nordhausen, where the secret underground factory in which the Luftwaffe developed the V-2 rocket was located. At least 20,000 slave laborers died there, it is estimated, 100 of them a day by war’s end, mostly due to starvation and exhaustion, but also thanks to mass hangings carried out not just by the SS guards but apparently also by some rocket scientists. (Only 11 of the roughly 3,000 SS officers who served there were ever arrested.)

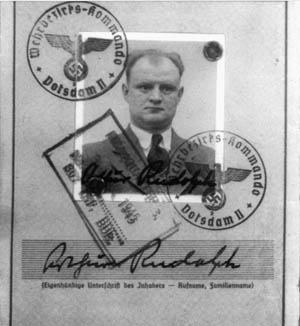

One such scientist, Rosenbaum came to be convinced, was Arthur Rudolph, who by the 1980s, his past all but forgotten, was a venerated figure at NASA, known as the father of the Pershing Missile and the Saturn V Moon rocket and the recipient of NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal. And yet he’d been not just a cog in Hitler’s war machine, Rosenbaum’s investigation suggested, but an early admirer of Mein Kampf and a Nazi Party stalwart.

Allan Ryan recalled, “Here’s a guy without whose efforts we probably wouldn’t be on the moon. I asked Eli, Why should we send this guy out of the country? He said, This was not some desk jockey. This was a guy whose idea of motivating workers was to hang bodies on hooks and send them around the premises. And we had the goods on him.”

Rudolph apparently agreed. After three interviews with OSI, he agreed to renounce his U.S. citizenship, and returned to Germany in 1984, despite outcries from assorted military brass and politicians, including Patrick Buchanan, then White House communications director, and, more disastrously, former Ohio congressman and sartorial innovator James Traficant, who organized a rally for Rudolph on the Canadian side of the Peace Bridge near Niagara Falls. The legislator and rocket scientist were joined by a phalanx of neo-Nazis, and then turned away at the border. Rudolph later claimed he was coerced by OSI into his renunciation. (When he was released from federal prison in September of last year, after serving a seven-year term for taking bribes and racketeering, Traficant gave an interview to Fox News decrying Demjanjuk’s deportation, a showing that has probably not helped Demjanjuk’s standing.)

The OSI’s Major Cases

Defense attorney Michael Tigar was right about Rosenbaum in at least one respect: he is a true believer. “What makes it satisfying is that the crimes involve so many victims, and they were committed at a place that is as close to hell on earth as has ever existed,” he told me. So, too, is much of his staff. OSI “was not just a moral or professional attachment—it was a visceral attachment,” Bruce Einhorn, a retired federal judge and OSI prosecutor in the 1980s, said, “It was the one job I’ve had when I woke up in the morning and looked in the mirror, I was proud of my client, and when I went to sleep at night I knew what I’d done that day was important.”

Ronnie Edelman, a former OSI attorney who prosecuted Artukovic, said “The contrast between what he did and what he appeared as when we tried him was pretty extreme, but I never felt we shouldn’t be doing it. Did I see him as a man, as an individual? Yes. But it didn’t excuse what he did. It just seemed you couldn’t ignore that. We tried him with all of the protections of our justice system, which was far more than his victims received. It was worth doing for the historical record and to give some element of justice to the victims.”

Trifa’s and Rudolph’s were major cases. But then, by historical standards, all of OSI’s cases could be called major. “If you want to dedicate yourself to law enforcement, most people want to work on cases involving the worst criminals,” Rosenbaum said. “You’d be hard-pressed to find worse criminals than Nazi war criminals.”

There was the case of Luidas Kairys, who’d served as a guard platoon leader at Treblinka. When OSI tracked him down, Kairys was working at a Cracker Jacks plant in Chicago.

There was Aleksandras Lileikis, chief of the Security Police in Vilnius, which sent thousands of Lithuanian Jews to their deaths at the hands of the Nazis. After the war Lileikis took up a quiet life as a printer on a quiet street in Norwood, Massachusetts. For 10 years OSI investigated him without luck, until one morning one of its historians, sifting through papers at a prison in Vilnius, found a box of files of people arrested by Lileikis and later executed.

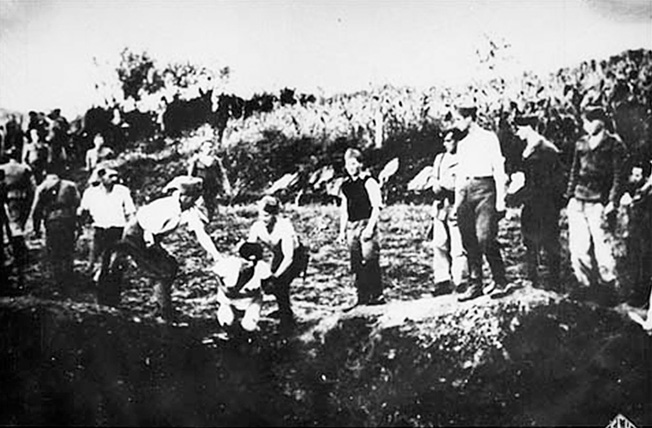

There was Helmut Oberlander, the wealthy German-American real estate developer who was at his winter apartment in Marco Island, Florida, when Rosenbaum (who left OSI in 1984 to work as a corporate litigator and then at the World Jewish Congress and returned in 1988, becoming its director in 1995) knocked on his door. Until that point Oberlander had managed to hide from his family and friends that he’d been an interpreter in a unit of Einsatzgruppe D, a mobile killing detachment whose sole job was to wipe out Jews, partisans, Gypsies, and others on the Eastern Front. Einsatzgruppe D is thought to have killed more than 90,000 Jews in Ukraine, mostly by machine-gunning them in mass graves. Oberlander fled to Canada, where he is now a wealthy retired real estate developer. In November 2009, a Canadian court again declined to deport him.

Other defendants and subjects of OSI investigations have fled to Costa Rica, Hungary, Paraguay, Estonia, Venezuela, even Germany. Some have taken other routes of escape. Elfriede Rinkel was a SS guard at Ravensbruck. While researching her whereabouts, Rosenbaum came upon an obituary for her husband. He couldn’t believe what he read: the man had been Jewish, a refugee from Germany. When Rosenbaum interviewed Rinkel in her house in San Francisco, she showed him a photo of her husband’s tombstone. An empty space next to his name awaited hers, and over it was chiseled a Star of David. Rinkel admitted she’d never told her husband what she’d really done during the war. “I was glad I didn’t have to do that case at a time her husband was alive,” Rosenbaum said. “That would have tormented me.”

The Interrogation of Jakob Reimer

Interviewing survivors and convincing them to recount their stories is the more wrenching part of his job, Rosenbaum said. “Almost all of them have a point where they break down and cry. I see that coming and I’m pretty sure the next question I ask is going to send them over the edge––and I feel so guilty and so sad,” he said. “In some cases they haven’t recalled their experiences in this level of detail since the war’s end.”

“It was the most inspiring and eventually the most draining experience of my life,” Bruce Einhorn said of interviewing survivors. “I would have to make these very good people not just recall but, let’s face it, relive these experiences.”

Perhaps the most grueling interrogation Rosenbaum has ever conducted, though, was of Jakob Reimer, a SS battalion commander who, it is now believed, directed executions during the liquidations of the Jewish ghettos in Warsaw, Lublin, and Czestochowa, Poland. After the war, he changed his name to Jack Reimer and immigrated to New York, where he worked his way up from a night janitor at a Schrafts restaurant in Times Square to its manager, and lived in a little house in Putnam County.

Reimer, who admitted to being SS when he came to the States, had already been interviewed twice by authorities and let go. He arrived at the interview with Rosenbaum without a lawyer, prepared to walk off again. But Rosenbaum suspected Reimer had a story to tell. And after two hours of questioning, Rosenbaum had Reimer describing a mass execution in which about 50 men were shot to death in a pit in the forest. But Reimer claimed he went out of his way not to kill anyone. “It was a battle of wits. He was trying to discern what I already knew, and I was trying to conceal it,” Rosenbaum said. The interview transcript runs to 174 pages. By page 150, Rosenbaum had Reimer on the verge of admitting that he’d pulled his trigger. The back and forth arrives at this climax:

Rosenbaum: Weren’t there some people who were still alive down there who had to be finished off?

Reimer: There was one—I don’t know—was he half dead or whatever. He was pointing with a finger to his head.

Rosenbaum: He wanted to be shot?

Reimer: Yes. And I don’t know who but he was shot. That is all I saw. That is the only one that I saw that was shot in my presence when one of them already in the grave pointed the finger to his head, begged for mercy, so to speak.

And then:

Rosenbaum: There’s something about the man who pointed to his head that you haven’t told me?

Reimer: Yes.

Rosenbaum: You finished him off.

Reimer: I’m afraid so. I don’t know if I hit his head. I don’t know that.

Rosenbaum: But he died?

Reimer: I just say that I had to make one effort at least while the German was looking at me where I was.

“We ended up in court having to make the grotesque analysis that even if Reimer’s bullet didn’t hit the man, that between the time he saw Reimer pointing a gun at him and the time he died, even if it’s just a second, that’s serious persecution. It was a very awful situation to be in,” Rosenbaum said.

Sealing Reimer’s Fate

Reimer’s lawyer, former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark, told me he believes to this day what Reimer told him—that he intentionally shot over the heads of victims. “Reimer was an absolutely tragic case,” Clark said. “He was a totally nonviolent person. What’s he supposed to do, stand there and let the [German] sergeant shoot him?” Clark suggested that Rosenbaum may have committed entrapment by suggesting to Reimer he knew something he did not, an argument Clark did well not to raise in court: law enforcement personnel suggest foreknowledge to interview subjects all the time. It’s part of the job. Clark also recounted that as he and Reimer sat eating in the courtroom cafeteria one day during the trial, a woman came over and spat in Reimer’s face. “There’s fanaticism behind OSI. It fuels hatred,” he said.

But Reimer’s fate was sealed when OSI tracked down, in a village north of the Ural Mountains, a man who’d served under him in the SS Battalion Streibel. In his testimony, the man recalled seeing Reimer and two co-commanders directing executions, using “their rifle butts to prod the victims, forcing these fear-crazed people to stand up from the ground in groups of five to seven people, including men, women, children, and old people, and marching them into the pit. Then, together with the German officers, they shot the Jews.”

“Probably a million people died that way over the course of the war,” Rosenbaum said. He added: “I remember thinking that if [Reimer] was a guy who I didn’t know what he’d done, I’d feel perfectly fine letting him babysit my children.”

The War Criminals That Never Made Trial

For every Reimer, there are thousands who never turn up. OSI still maintains a watch list of 70,000 Nazi and Japanese war criminals—it includes the entirety of the 40,000-strong SS officer corps—that’s kept on hand at all international airports and ports of entry in the United States.

Reimer claimed in his testimony that his way to the States may have been aided by a German girlfriend who’d worked for U.S. intelligence after the war. This may or may not have been true, but it’s certainly plausible: Some of OSI’s most odious defendants were recruited by the government.

Such was the case with Andrija Artuković and Valerian Trifa, CIA and FBI assets, respectively, and with Arthur Rudolph, a beneficiary of Operation Paperclip, an Army Intelligence initiative to recruit Nazi scientists as part of what was known as the “intellectual reparations” agenda. It was summed up by Dwight Eisenhower when he pointed out that such minds as Rudolph’s were “about the only material dividend we are likely to get from the war.”

Even while the Allies hunted fugitive Nazis across Europe, they enlisted them. Morally questionable perhaps, this also proved fruitful beyond all expectations: the Axis was years ahead of the Allies in the development not just of missiles, but sonar, jet engines, swept-wing aircraft, synthetic minerals, and chemicals—some of the very things that would fuel the postwar economic and scientific booms in the United States.

Hideous though it is to contemplate, the knowledge gleaned from torturous pressure-chamber experiments carried out on prisoners at Nordhausen proved invaluable to the development of the aviation medicine needed for manned space flight. Indeed, it’s no exaggeration to say that without Rudolph and his compatriots—most famously Werner von Braun, the father of NASA, whom OSI may well have prosecuted had he not died in 1977—there probably would be no American space program.

Operation Public Interest

The CIA’s answer to Paperclip was called (apparently with a straight face) Operation Public Interest, and among its recruits were OSI defendants Aleksandras Lileikis, Tsherim Soobzokov, and Vladimir Sokolov, the last a Nazi propagandist. By the point OSI tracked down Sokolov’s writings—including an oath declaring, “I give my solemn pledge of Loyalty to Adolf Hitler, the Liberator of the Peoples of Russia, and the Unifier of New Europe”—he was a beloved professor of Russian literature at Yale.

William F. Buckley came to his aid, as did the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich and Pat Buchanan, who unsuccessfully tried to enlist Ronald Reagan to intercede on Sokolov’s behalf. (Sokolov was later deported and died in a monastery in Canada.)

The same restraint was not shown by Reagan’s predecessor. In 1987 Jimmy Carter wrote a letter to OSI on behalf of Martin Bartesch, a one-time guard at Mauthausen. In Germany the U.S. government had captured, and OSI had found, a document that came as close to a smoking gun as it gets in such cases—a log-book, with Bartesch’s signature, in which he’d confirmed personally executing a Jewish prisoner. Nonetheless, the former president implored OSI, “I hope that, in cases like this, that special consideration can be given to affected families for humanitarian reasons. Jimmy Carter.”

The most shameful case was that of Otto Von Bolschwing, a top-level CIA catch who parlayed his connections into a career as a technology consultant in Silicon Valley. On its website, the CIA calls von Bolschwing “one of the Agency’s leading agents in Austria after World War II” and his case “perhaps the most important Nazi war criminal case involving a CIA asset.” Not only a high-ranking SS officer, he also served as a tutor on Judaism to Adolph Eichmann, the architect of the Final Solution, whom he helped design the framework for expropriating Jewish property. The CIA routinely lied to immigration officials to get Nazis into the States. But the Agency claims it didn’t learn the full extent of von Bolschwing’s involvement until decades later. OSI denaturalized him in 1981.

“We Turned the Clock Back to 1945”

When I asked Rosenbaum whether he sees OSI’s job as in part righting some of the sins of the Cold War, he said, “One encounters in this work any number of incidents involving troubling conduct on the part of U.S. government personnel, and while one can’t completely undo the consequences of those actions, I do think pursuing justice in those cases at least helps set the record straight and reveals the truth.”

In fact, OSI was one of the few offices in Washington to have any contact with the Kremlin toward the end of the Cold War. “We turned the clock back to 1945. We were all going into court together against the Hitlerite criminals, and it had to get done,” Ryan said.

OSI has come in for criticism on this score, its foes claiming that it has been duped by Soviet forgeries and coerced confessions. The prior argument has been roundly dismissed by judges at every level, and rightfully so: in the majority of investigations that have led OSI to Russian archives, the records have exonerated defendants or proved insufficient to show guilt. Over its history OSI has initiated 1,500 investigations, but only brought 137 cases. But the latter argument has validity, or at least did prior to the demise of the USSR. Rosenbaum said cooperation with OSI “had practical value for the Soviets as a propaganda matter, I can’t deny that. But that having been said, for a variety of reasons the evidence they provided was authentic and as reliable as evidence found elsewhere. Whenever we had good evidence, we used it.”

Bertram Falbaum, a former OSI investigator, said, “I once asked a Soviet procurator, Why are you so cordial and accepting of us coming over? And he said, Listen, from your point of view, seven million Jews, Gypsies, clergy, and others were killed by the Nazis. From our perspective, 20 million Russians were killed. Why wouldn’t we cooperate?”

The Guilt of the Camp Guards

Still, the majority of OSI cases have involved men, like Demjanjuk, who were low-ranking camp guards. “No one ever asks the most important question: Who is this man and why was he there?” said Joe McGinness, a defense attorney who’s represented nine OSI defendants. According to McGinness, and to certain WWII historians, many camp guards were dragooned into service and had little or no choice where or how they served. “If you say I’m not going to do it: If you’re lucky they send you back to the potato field. If you’re not lucky they send you to a camp. If you’re really not lucky, they shoot you on the spot,” said John Broadley, a lawyer who represented Demjanjuk.

But former OSI historian Todd Huebner disagrees. “There is a lot of evidence that camp guards could have said no to entering training and going into SS service at these places. On the other hand, I don’t know how much I’d trust things to be fine and dandy if I said no to [the Germans].” Though “they had no control over where they were sent,” he said, “these people were under absolutely no compunction to come to the U.S. and lie about these things.”

“None of these men were just present at these camps. Because of what a camp was, all of them took part in persecution, usually lethal persecution,” Rosenbaum told me. “That’s what the Supreme Court found, and it makes sense. The raison d’etre of a labor camp was persecution, and in many ways death, and if it was a death camp, it was flat-out murder. Do I recognize that are different levels of responsibility and culpability? Of course. But there is a standard for entry into the United States.”

“My Client Was Deemed Guilty Even Before We Got Into Court”

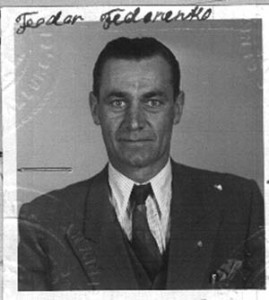

The Supreme Court decision Rosenbaum referred to involved Feodor Federenko, a Treblinka SS guard who was deported to the Soviet Union, where he was tried and convicted of treason, and sentenced to death in 1987. His lawyer, Brian Gildea, recalled being woken up by a phone call from Moscow at 2 am. A voice on the other end informed him his client had just been shot to death by a firing squad.

“I actually thought he was a decent man, and believed the things he told me about his presence in Treblinka. He said, I never, never hurt anybody. But [Allan] Ryan was convinced he beat people,” Gildea, who’s represented 10 OSI defendants, said. “Every single one of the cases I handled, there was speculation and vague testimony of violence, but there was never hard evidence in German or Russian archives that any of the people I represented committed a crime, murdered, or beat somebody at one of these camps.”

“It seemed to me my client was deemed guilty even before we got into court,” Gildea said. “There was absolutely no compassion at all for my clients. [OSI] were on a mission. They took it very personally.”

Others took it more personally. During the Federenko litigation, Gildea received death threats. “My wife picked up the phone one day and a voice on the other end said ‘Your husband is a fucking Nazi and we will kill him,’” he said. His car was checked by state troopers for bombs every morning before he could pull out of his driveway.

Artukovic’s lawyer, Gary Fleischmann, who is Jewish, said the Jewish Defense League picketed his house for months. The group’s leader barged into Fleischmann’s law office in Beverly Hills one day and loosed a potbelly pig. (The JDL also took credit for the pipe bomb that killed Tsherim Soobzokov.) Because he elected to represent Artukovic, “My nephew didn’t speak to me for six months,” Fleischmann said. “There are people who don’t speak to me to this day.”

Did the OSI Withhold Evidence in the Artukovic Case?

Though what still bothers Fleischmann—and other defense attorneys—most is his suspicion that OSI suppressed potentially exculpatory evidence that might have lessened the case against Artukovic. Gildea made the same claim about Federenko. Their claims may have merit. There is no question that OSI lawyers had documents suggesting Demjanjuk was not Ivan the Terrible, which they didn’t show to Israeli prosecutors.

“They had evidence in their files that should have been turned over—it was that simple. That’s prosecutorial misconduct of the worst kind, especially if he’s going to be tried in a foreign land for a capital offense and sentenced to death. I mean, that’s egregious,” said Gilbert Merritt, a judge on the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, who ordered an investigation of OSI after Demjanjuk’s exoneration in Israel.

Though OSI was officially cleared of wrongdoing by an independent investigator, and Merritt agreed that Demjanjuk had served as a camp guard and entered the United States illegally, he told me his “view of it was that Justice whitewashed OSI’s failure to turn over to the court certain information.”

Rosenbaum, who was absent from OSI for the first Demjanjuk trial and did not take it over until after the Israeli exoneration, speaks about the case with an audible tone of vicarious regret. He won’t admit that OSI lawyers acted improperly, however.

Critics of the OSI

The most common accusation leveled at Rosenbaum and OSI is that they are out for vengeance, not justice. This is a plausible accusation made less so by the people leveling it.

On the opposite side of the fray from the hotheads of the Jewish Defense League, OSI’s cases have attracted a motley cast of amateur historians, activists, Holocaust-revisionists, or outright deniers. No less a whackadoo than Lyndon LaRouche has held anti-OSI rallies at his Virginia home. There are those, like Ramsey Clark, who are concerned with hypocrisy. Clark told me, “My sense of a just society and what justice is––there has to be a time when you forgive, when you try to overcome the wrongs, and recognize that humans are fallible and these people were caught up in events beyond their control. We forget the horrors of WWII all around. Look at the [Allies’] firebombing of the German cities.” He added, “The pursuit of these people has been an industry. These are not Eichmanns. [OSI is] a blemish to our law.”

There are those like Joe McGinness who repeatedly put on the witness stand a travel agent and self-styled scholar who questioned basic elements of World War II history. McGinness, who called Rosenbaum “an impresario of fraud,” could barely contain his contempt for what he sees as OSI’s real mission. “They are in the business of educating people in this country about the Holocaust, and they need a body. They need someone to put at Mauthausen, or some place else,” he told me. McGinness won one of the nine cases he’s tried against OSI. “These people to the man were the nicest people I ever met in my life. I never had nicer clients,” he said.

And, finally, there are those like Heinz Bartesch, the son of Martin Bartesch. OSI’s goal, he told me, is “to keep the Holocaust on the minds of everybody. Like we need more. Here’s an event that didn’t take place in the U.S., but we have umpteen Holocaust museums across the U.S. Why do we have to make the Holocaust a national religion?” I was not surprised to hear Bartesch say this, as he’d just informed me that it “wasn’t Hitler’s plan to exterminate the Jews of Europe.” He posited that “these were internment camps, not death camps. They had huge kitchens, health care. They were set up to house people until such time as [the Nazis] could send them to Palestine.”

With such ideas, it’s not surprising that Bartesch was unable to prevent his father’s deportation (even with Jimmy Carter’s aid). But then the spectacle of watching one’s parent investigated and tried for being a war criminal, and then deported, is unthinkable in its own way. It would be enough to drive anyone to distraction, or at least denial. OSI cases bedevil families for years and decades. They drive people into bankruptcy, or exile, or both. “There is no getting around the fact that other people suffer,” historian Todd Huebner said. “Their wife didn’t work at a camp, their kids didn’t kill anyone.” And how do you face accusations like these? How could even the most honest person come to believe his or her father is responsible for the murder of one person, let alone hundreds, or thousands? Most, of course, can’t. Bartesch, like Demjanjuk’s children and Rad Artukovic, will probably maintain their fathers’ innocence to their own dying days, no matter how compelling the evidence against them, and accuse OSI of fraud in the bargain.

Joe Eszterhas’s Writings

One child of an OSI defendant who went in the other direction, though, is Joe Eszterhas, the screenwriter of Music Box. In a coincidence so eerie as to seem almost biblical, several years after the film was released Eszterhas’s father, Istvan, received a letter from Rosenbaum: he was being investigated for authoring anti-Semitic propaganda that led to the murder of Jews in wartime Hungary. When OSI brought the case, Rosenbaum said, he did not know Istvan was related to Joe, who’d gained fame as the writer of Flashdance and Basic Instinct. (Rosenbaum still has not seen Music Box.) Eszterhas would not speak for this article, but in his memoir Hollywood Animal, he describes the ordeal unflinchingly. “As the hearings continued, I felt like I was being buried in an avalanche of filth,” he writes. Rosenbaum, whose professionalism and courtesy Eszterhas praises in the book, eventually decided not to prosecute––but not before Eszterhas became convinced of his father’s guilt. Standing at Istvan’s hospital bed, after the sickly, 85-year-old man has undergone heart surgery, he writes: “I wanted to say ‘I forgive you’ but I couldn’t form the words.”

Prosecuting John Demjanjuk

The Demjanjuk case was a pyrrhic victory for Rosenbaum, and the old Ukrainian’s defenders don’t just question his guilt—they take his innocence for granted. That’s how badly OSI fumbled the case the first time. In November, Esquire ran an article on the case whose teaser posed the question, ‘Is this one last blow struck for justice for the Holocaust? Or is it a farce?’

“He has, for 30 years, endured harassment, persecution, and perjury which destroyed his life and that of his family,” one of those defenders, Pat Buchanan, told me. Buchanan, who once said Demjanjuk’s ordeal “may be an American Dreyfuss Affair,” first took up his cause in the first Reagan administration. He said he “know(s) of no witness, living or dead, who has credibly testified he saw John Demjanjuk kill anyone. I regard John Demjanjuk as a victim of a monstrous injustice perpetrated by people so blinded with hatred they cannot see the evil they do.”

OSI cases take an internal vengeance, too. Its lawyers and historians become consumed. John Horrigan, a former OSI investigator who worked on Demjanjuk’s case in the 1980s, admitted that “prosecuting him, for all of us, became an obsession.” Todd Huebner said, “My first gray hairs appeared while working on the Demjanjuk case,” adding, “I didn’t have a very upbeat view of human nature to begin with, and this job didn’t give me a more upbeat view.”

Rosenbaum said, “For a lot of people here, the nature of the work exacts a serious toll emotionally. It’s very depressing work.… I worked here from 1980 to 1984, and at that point I’d seen as much devastation and murder as I could really handle, and I just needed to get away from it. The reason I’ve been able to survive the second go-around is I don’t deal with the reality of these crimes on a daily basis. I’m an administrator now.”

He will have to deal with the reality at least one last time: he’s scheduled to fly to Munich to testify against Demjanjuk, who will most likely spend what little time he has left in life after the trial in a prison cell in Germany, which does not practice capital punishment. (Huebner said the current case is more or less airtight. “No case I worked on had as many and as useful documents as Demjanjuk,” he said.) It will no doubt prove one of the world’s last Nazi trials, not because OSI has a lack of active cases, but because of the “biological solution,” as it’s mordantly known around the office. Over 90 percent of its defendants have already died.

Giving OSI a Modern Focus

That’s why the Justice Department has instructed Rosenbaum to begin concentrating on cases of modern war criminals—from Africa, the former Yugoslavia, South America, and Asia—who’ve immigrated to the States.

“We got a call from an African man who encountered his one-time torturer in his apartment building,” Rosenbaum told me. “That experience is unlike anything the survivors of the Holocaust have had. There are no Nazis dressing up as Jews and going to synagogues.”

In the spring of 2009 OSI brought its most significant modern-era case to date, against Lazare Kabaya Kobagaya, who lives in Topeka, Kansas. Kobagaya is accused of playing a major part in the 1994 Rwandan genocide. It will be a respite of a sort for Rosenbaum. But only of a sort. The unthinkable brutality of Rwanda in 1994 does bear some resemblance to the unthinkable brutality of Europe in 1943. Prosecuting horror means reconstructing it, and reconstructing it means, in some sense, living it.

“It’s easy to burn out on this kind of work,” Rosenbaum said. “You try to imagine what it was like to be there. And no sooner do you start, than you try to not imagine what it was like.”

This was a very eye-opening article. Not about the war and all of its well-known horrors that as many readers already know can ever be fully understood by anyone who didn’t live through those days like many of our parents had. But what surprised me was how many people whom I had not always agreed with but had enormous respect for interceded on behalf of war criminals they knew personally saying what good upstanding people they were. It’s like they never realized ordinary people did do those things and anyone who can convince you of absurdities can convince you to do atrocities. These men and women were not born monsters but lies and propaganda can turn people into monsters who truly believe they are doing the right thing. If Germany had won the war these same people would have continued doing those same horrible things thinking it was the will of God.