By Stephen D. Lutz

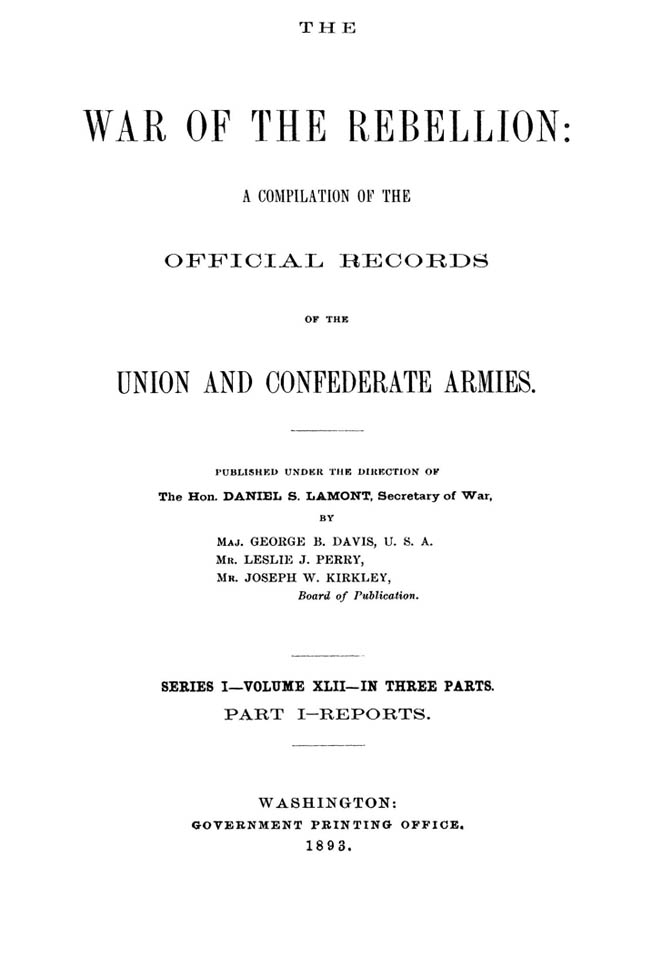

The title of the 128-book, 138,579-page work was a suitably large mouthful: The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.

It took half a dozen people overseeing the work to get it done, beginning with Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, general-in-chief of the Union armies from July 1862 to March 1864. One task befalling Halleck was reporting to Congress at least once yearly on the progress of the war. Halleck, an 1839 West Point graduate with 24 years in the Army, got to do such a report in 1863. What made the reporting process particularly difficult was the need to sort through an ever-mounting collection of paperwork: orders, battle plans, after-action reports, casualty lists, communiqués between civilians and politicians to military leaders, and humdrum daily comings and goings of a multi-million-man army. There was no organization in how the reports came in or were sorted out. A harried Halleck turned to Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson for help.

Henry Wilson’s War History

The 51-year-old Wilson, one of the Republican Party’s founding members, would hold a Senate seat from 1855 to 1873. In 1863, as chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs, Wilson had collaborated with Halleck on a legislative proposal to provide funding, personnel, and resources to collect, sort, and catalog all the paperwork detailing the Union war effort. On May 20, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed his approval to the bill mandating congressional responsibility to launch the project. That began a 37-year-long project of numerous starts and stops before concluding in 1901 with the 128-volume collection.

Once approved by Congress, Halleck got the project up and going. His first step was to put it into the hands of 27-year Army veteran, Edward D. Townsend. As assistant adjutant general, Townsend had no background in the publishing, editing, or printing business. His job was to collect material, sort it out, and make it presentable for book publishing. The job of publishing went to the Superintendent of Public Printing for the U.S. House of Representatives, Joseph Hutton Defrees. Unlike Townsend, Defrees had a long acquaintance with the printing and publishing business before becoming an Indiana congressman from March 1865 to March 1867. Before that, he had enjoyed an extended political career within the state of Indiana.

The project’s initial goal was to publish 10,000 copies of a complete official history. Six months into the project, Townsend sent Defrees six volumes to be reviewed and accepted for publishing. Defrees was not impressed with what he read. Given the overall lack of available Confederate documents, Defrees saw that he was sorely lacking that side of the story. It read heavy handed and one sided. Nor was there any cohesion to the readable content. The entire project was scrapped—and Townsend along with it. Henry Wilson set about revising the approach.

In mid-July 1866, Wilson approached Congress about revitalizing the official history quest. Then the bickering started. Wilson proposed a targeted budget of $500,000 to see it through. Opponents argued that the final cost would easily exceed $1 million. Wilson also stated his belief that the history could be covered within 50 volumes. Others insisted it would take as many as 500 volumes. On July 27, 1866, the two sides reached an agreement. The original goal established in 1864 would be erased from the congressional books.

President Andrew Johnson signed his approval to the new two-year plan to kick start the project. The leading clause to that agreement was finding somebody competent enough to see the work through. That led to Peter H. Watson, a former assistant secretary of war for one week in the last week of January 1862. By July 27, 1868, the project again was at a standstill. Meanwhile, the chief goal of Congress was a burning desire to scavenge every single piece of official Confederate documents to see what—if any—evidence could be found linking former Confederate President Jefferson Davis to President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. For many that was their priority.

Another Disorganized Attempt

By 1874, a growing segment of the American public was clamoring for the government to make another go at compiling the records into a multi-volume set. Civil War veterans from both sides had created their own veteran awareness organizations. They wanted their history of the great American cataclysm recorded for posterity. They turned for help to a fellow Civil War veteran, Ohio Congressman James A. Garfield. Between 1874 and 1876, at Garfield’s urging, Congress doled out separate allotments totaling $100,000 to fuel the project once more.

Unfortunately, Edward Townsend was put back in charge of the project. Work proceeded just as sluggishly as it had during his first run at it. The result was a mirror image of what Townsend achieved the first time around: total chaos in written format. The system Townsend imposed would never be functional.

On July 31, 1876, Congress coughed up another $40,000 and put War Department clerk W.T. Barnard in charge of Confederate operations. Chief Clerk H.T. Crosby took Townsend’s place overall. There was still no magic after 10 months. On May 26, 1877, another clerk, Thomas J. Saunders, worked his way up the career ladder. All that Congress got for its money was one misshapen effort after another.

Between March and December 1877, an additional $100,000 was added to the project’s coffers to urge the work along. All that Congress got for its money was a scattered series of spasmodic work productions. By then a total of 37 volumes addressed the Union war effort; 10 others gave the Confederate side. Everyone who read them found fault after fault. Absolutely no cohesion existed. There was no easy way to follow any selected event or find collaborative connections to any other event. Volume after volume had to be surveyed to find the connecting points.

Robert Nicholson Scott’s 10,000 Copies

Secretary of War George Washington McCrary had been a Republican state senator in Iowa before becoming a United States congressman from 1869 to 1877. On March 12, 1877, he became incoming President Rutherford B. Hayes’s new secretary of war. McCrary would be the one responsible for seeing that the right person got into the right position to get things done. He hit upon Robert Nicholson Scott, who took over the records project on December 14, 1877.

Scott was born on January 21, 1838, in Winchester, Tennessee. At age 19 he became a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army’s 4th Infantry Regiment. Scott began his Civil War service in Company C of the 4th Infantry Regiment. From there he moved up to being regimental adjutant. Following field experiences at Yorktown and Gaines’ Mill, Scott became a staff officer in Henry Halleck’s inner circle. He ended the war as a captain with the 3rd Artillery, which took him back to the West Coast. In mid-December 1877. McCrary put Scott into a new job. Scott would become the most influential individual putting together the official records of the war.

Scott was given authority to do whatever it took to get the job done. Between June 20, 1878, and March 3, 1879, Congress gave him a total of $80,490 to further fund the project. In return, Congress wanted 10,000 finished copies for its investment. Scott wasted no time applying restrictions as to what would be acceptable for printing. All submitted material had to have been generated during the war itself, between April 1861 and April 1865. In addition, what was submitted had to be verifiable. The one thing Scott adamantly refused to see come his way was war stories. Although participants of the war were welcomed to read the final work, there would be no challenging a document from somebody’s decades-old, after the fact recollections.

Documents From the Confederacy

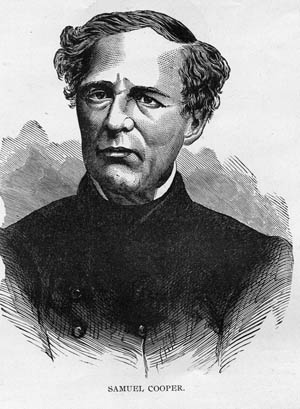

Fruits of Scott’s herculean labors were realized in June 1881 when the first volumes became public. But for all that Scott was doing, and doing extremely well, he kept running into a chief roadblock. Where were more Confederate documents? The answer to that question lay with Samuel Cooper, the former inspector general for the Confederate Army.

Cooper was born June 12, 1798, in Hackensack, New Jersey. Fifteen years later he became a cadet at the Unites States Military Academy at West Point. Completing the academy’s two-year program during that era, at age 17 Cooper became a second lieutenant in the artillery. He would wear a military uniform for the next five decades.

Cooper’s only combat exposure came in 1841-1842 in the Seminole War. By the time the Mexican War got underway, Cooper was a mainstay in the exclusive corridors of the War Department. By 1852, he held the post of the Army’s chief adjutant general, making him the Army’s chief administrative officer. Essentially, if anything appeared on paper having anything to do with the Army, Cooper had some knowledge of it. When Virginia seceded, Cooper “went South” as well. By then he had worn the U.S. Army uniform for just over 45 years. At age 63 he became the Confederate Army’s inspector general. In terms of total time in service, regardless of which uniform worn, nobody in the Confederate Army outranked him. Even Robert E. Lee was subordinate to Cooper.

In the first three days of April 1865, Richmond burned. Regardless of who lit the first matches, the city burned literally to the ground, including the war records of the Confederate Army. Tons upon tons of Confederate paperwork went up in smoke. Confederate President Jefferson Davis fled Richmond on a train with a selected entourage. Cooper was among that crowd with his private collection of personal baggage. Going as far as Charlotte, North Carolina, Cooper departed the train. He found an empty warehouse and stored his baggage there. Then he waited for the inevitable. That came on May 7, 1865.

On that day 24-year-old Captain Morris C. Runyan led Company C, 9th New Jersey Infantry into Charlotte. The city was in a state of near anarchy. It would be up to Company C to restore some sense of civil order and obedience. Part of that task meant searching out hidden weapons stores. Coming upon a locked warehouse a forced entry was made. Inside Morris and his crew found scores of Union Army battle flags strewn haphazardly across the floor. Then came stacks upon stacks of boxes. This is what Cooper left to be stored and kept from wanton burning. The 81 crates contained official Confederate documents Cooper refused to leave behind. He wanted them saved to afford posterity an accounting of the Confederate Army. It was reported that what was found weighed 10 tons.

Meanwhile, Halleck was in Richmond overseeing what documentary history could be saved. Word came to Runyan to box up everything he had found and send it off to the War Department—it did not matter if it was a single sheet of paper found lying off to the side. In the end, nothing was done with Cooper’s records for the next 13 years, when Scott finally unearthed them from the blizzard-wracked mountains of files.

So sure was Scott that he had cracked the case that he managed to squeeze another $80,000 out of Congress between June 1878 and March 1879. Still, despite the rediscovered Cooper files, it was felt that the Confederate side was missing sufficient quality accounting. Then came Marcus J. Wright.

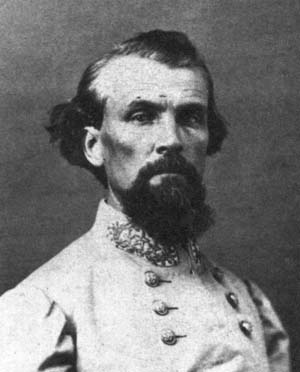

Former Confederate General Marcus J. Wright commanded the 154th Tennessee Infantry Regiment of Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham’s division. In due time, Wright became a staff officer among Cheatham’s influential group. Following the war, Wright became a recognized U.S. Navy purser in Washington, buying the stores needed by any given ship for sea duty. Being close to the War Department, Wright became aware of Scott’s wearying efforts to go through collected Confederate documents. As a former aide and staff member of Cheatham’s, Wright had his own secreted stash of official documents he had yet to reveal. Upon presenting his collection to the War Department, Wright received $2,000 and a new job as a special agent for the War Department in charge of procuring more Confederate documents. He was good at it.

Nearly a decade and a half after the war, many Southerners still distrusted the federal government. Southern resentment over losing their war of independence still held fast. Many believed that repercussions would follow the exposure of new Confederate documents. Wright quickly proved his worth to the War Department. On July 1, 1878, Wright became a recognized official Federal agent for obtaining Confederate documents. The next day he got William Preston Johnston $10,000 for his records concerning his late father, General Albert Sidney Johnston, who had been killed at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862.

Wright’s approach to Johnston paid immediate dividends, opening doors across the South for the official records project. Wright gained access to contributions from individuals and heirs to such leading Confederate generals as Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, P.G.T. Beauregard, James Longstreet, Sidney D. Lee, Sterling Price, Lucius Polk, Edmund Kirby Smith, James R. Chambers, Samuel Jones, R.S. Ripley, A.P. Stewart, and William Steele. Jefferson Davis’s widow, Varina, pitched in her fair share of documents left from her deceased husband.

Henry M. Lazell and Frederick C. Ainsworth

With the additional Confederate contributions, work on the records project continued apace. Then, on March 5, 1887, Scott died. It may be said that he had literally worked himself to death. His immediate replacement was Lt. Col. Henry M. Lazell, a native of Enfield, Massachusetts.

Between 1879 and 1882, Lazell was commandant of West Point. At the time of Scott’s death, he was stationed at Fort Craig in New Mexico Territory. After replacing Scott, Lazell held that position for the next two years. The only major change in operations was the creation of a supervisory board as dictated by Congress. The formula settled on one military officer and two civilians acquainted with publishing at some point in their careers. When Lazell’s short tenure expired, George B. Davis stepped in to lead the new structuring.

Davis, like Lazell, was from Massachusetts. He enlisted in the U.S. Army at the age of 16, having told recruiters he was 18. Once in uniform, Davis advanced from company quartermaster sergeant to regimental quartermaster sergeant, seeing action in 25 major and minor engagements. He came out of the Civil War as a second lieutenant, spending the next two years missing the military life. A direct letter from President Andrew Johnson got Davis into West Point. He graduated in June 1872.

Upon becoming a major, Davis was assigned to the War Department and given a new job managing two civilians supervising the official records project. One was Joseph W. Kirkley, who had started as an ordinary clerk in the War Department and advanced to the position of senior lead clerk. The clerk, Leslie J. Perry, had seen service in the Civil War. Davis kept his new position until July 1, 1895, when confusingly named Major George W. Davis took over. All this time, Wright was still finding scattered Confederate documents.

The final noteworthy name attached to the project was Dr. Frederick C. Ainsworth. Born in Woodstock, Vermont, Ainsworth was 12 years old when the Civil War ended. In the early 1870s he enrolled in New York University’s medical program. Ainsworth found doctor life boring and joined the Army Medical Corps in November 1874. He went on to participate in the Army’s pursuit of Apache war chief Geronimo. Politics brought Ainsworth to the War Department in 1879, when Civil War veterans of both sides were clamoring for an accurate accounting of their war. The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), the most active and motivated Northern veterans group, led the charge. Congress scrubbed earlier veteran’s benefit application procedures and instituted newer, broader services designed to make it easier for Union veterans to gain recognition and compensation for their services.

When Ainsworth became the Army’s surgeon general in recognition of his medical experience, knowledge, and highly touted administrative skills, he streamlined federal offices. He took an antiquated index reference card system and put new efficiency into it. The existing system was as old as the Army itself. Ainsworth took the well-used index cards and wide assortments of paper and saved what was written on them. The original papers were of such poor quality that they were deteriorating. From Civil War records, Ainsworth moved backward to the Mexican War, the War of 1812, then the Revolutionary War, saving records of over 50 million former soldiers and sailors.

The Completed Project

Between the work of Ainsworth and Joseph W. Kirkley, the 128-volume War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies became a finished reality in mid-1901. The collective series was broken down thusly: Series I held 53 volumes, equaling 111 books. This material focused on Union and Confederate battle plans, preparations, after action reports, casualty lists, communiqués between commands at various levels, and those between military-civilian channels. Series II had eight volumes holding eight books and addressed prisoners of war. Series III contained five volumes of miscellaneous Union communiqués, military and civilian orders, logistics, reports, etc., not found in Series I nor II. Series IV had three volumes of primarily Confederate documents of conscription records and political-military exchanges, material that arrived too late in the publishing process to have been included elsewhere in previously edited volumes.

The final page count for all volumes was 138,579. The total cost across 30 years of effort was a staggering $2,858,514.67. Generations of future researchers, genealogists, and historians would call it a bargain at twice the cost.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments