By William Stroock

Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, presaging the subsequent surrender of other Confederate forces in the West and the capture of Southern President Jefferson Davis a few weeks later, marked the triumphant end of the nation’s great sundering. It should have been a moment of great celebration. Instead, five days after Appomattox, the capital city of Washington, D.C., found itself trapped in a grief-stricken stupor, locked in a mixture of sorrow and rage at the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln by Confederate partisan John Wilkes Booth. Lincoln’s assassination took away not only the nation’s 16th president but also its hard-won sense of joy and relief after four years of bloody conflict and unimaginable sacrifice.

As news of Lincoln’s assassination spread, many Washingtonians took to the streets demanding Confederate blood. In a driving rainstorm, shocked and enraged Washingtonians shouted, “Shoot them! Hang them!” A mob gathered outside Ford’s Theater, where Lincoln had been fatally wounded, chanting, “Burn the theater!” Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, for several hours filling the role of chief executive until Vice President Andrew Johnson could be sworn in, flooded the streets with Federal troops and cordoned off the city. Eventually tempers simmered down, leaving Washington cloaked in mourning. For five weeks the American flag on the White House grounds flew at half-staff and the great columns of the portico were swathed in black. Windows and doors throughout Washington showed black curtains and black wreaths. Citizens walked about town in a daze, dressed in black or at least wearing black armbands.

As the weeks passed, the grief slowly subsided. On May 10, with most Confederate forces having surrendered and the men in butternut and gray heading home, President Johnson declared hostilities “virtually at an end.” Six days earlier, the New York Times had urged that “before Sherman’s and Meade’s armies are broken up, arrangements will be made for a great military display when the public could express its obligations to these great and famous armies in some striking and worthy manner to both their soldiers and their leaders.” The new president, in one of the few shrewd political moves of his controversial and doomed tenure as chief executive, decreed that a Grand Review of the victorious Union armies should take place near the end of May. Preparations immediately got underway. After five weeks of mourning, the nation finally intended to celebrate its great victory.

Washington’s Population Swells

The capital had never seen anything like it. The town was still bristling with military personnel, a common sight after five years of war, but now tens of thousands of civilians thronged into Washington from across the Union. The New York Times estimated the number of people in the streets at 200,000. (Other estimates added another 50,000 to that number.) So severe was the sudden population influx that the capital’s hoteliers reluctantly turned away thousands seeking accommodations. Many simply slept in the open or stayed up all night partying—a task made harder, but not impossible, owing to the fact that the city’s saloons were closed for three days by official sanction to minimize the threat of brawling between soldiers and civilians. Numerous speakeasies gladly took up the slack. For those with milder tastes, street corner entrepreneurs offered purple lemonade. All drank with impunity, since law enforcement officers were too busy arresting pickpockets, prostitutes, thieves, muggers and counterfeiters to pay any attention to illegal drinking.

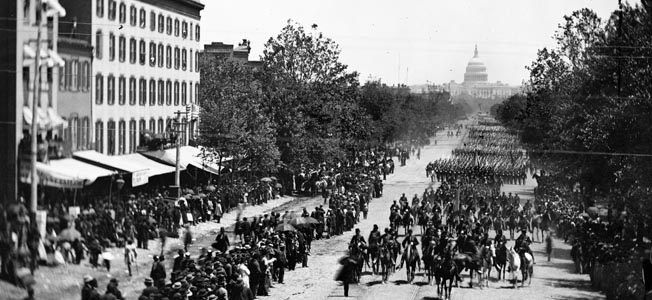

Some 150,000 Union soldiers descended on the capital—90,000 in the eastern theater’s Army of the Potomac, 60,000 in the Army of the West, compring the combined Army of Georgia and Army of the Tennessee. With them they brought 25,000 horses, whose daily mounds of manure were a logistical nightmare for city workers to cart away. Despite the overcrowding, the Times reported, the mood of the city was “gay and jovial with the good feeling that prevails, for the occasion is one of such grand import and true rejoicing that small vexations sink out of sight.” Poet Walt Whitman, then working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, saw the city positively jammed with soldiers as he walked down Pennsylvania Avenue. “The city is full of soldiers, running around loose,” he wrote. “Officers everywhere, of all grades. All have the weather-beaten look of practical service. It is a sight I never tire of. All the armies are now here (or portions of them) for tomorrow’s review. You see them swarming like bees everywhere.”

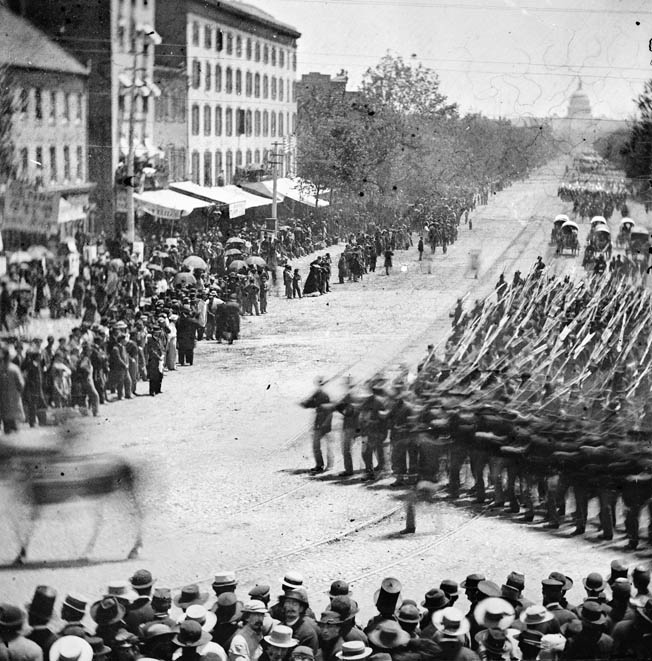

Crowds of Spectators

Massive crowds gathered along Pennsylvania Avenue. People hung out the windows of buildings along the parade route. Atop each building dozens of onlookers waved banners proclaiming victory and giving thanks to the Union Army. A giant banner stretched across the front of the Treasury Building proclaimed in all caps: “The only national dept we can never pay is the dept we owe to the victorious Union soldiers.” Many placards simply listed the great Union victories—Gettysburg, Shiloh, Vicksburg—almost as though they were political slogans. Church choirs and children’s choruses took positions along Pennsylvania Avenue, where a wreath of flowers stretched across the roadway. Thousands of onlookers held their own bouquets, wreaths, and garlands to throw at the feet of passing soldiers.

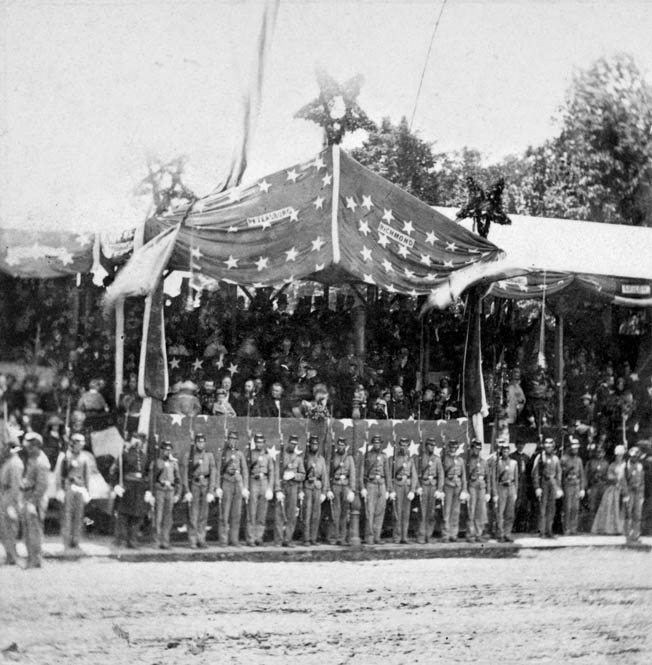

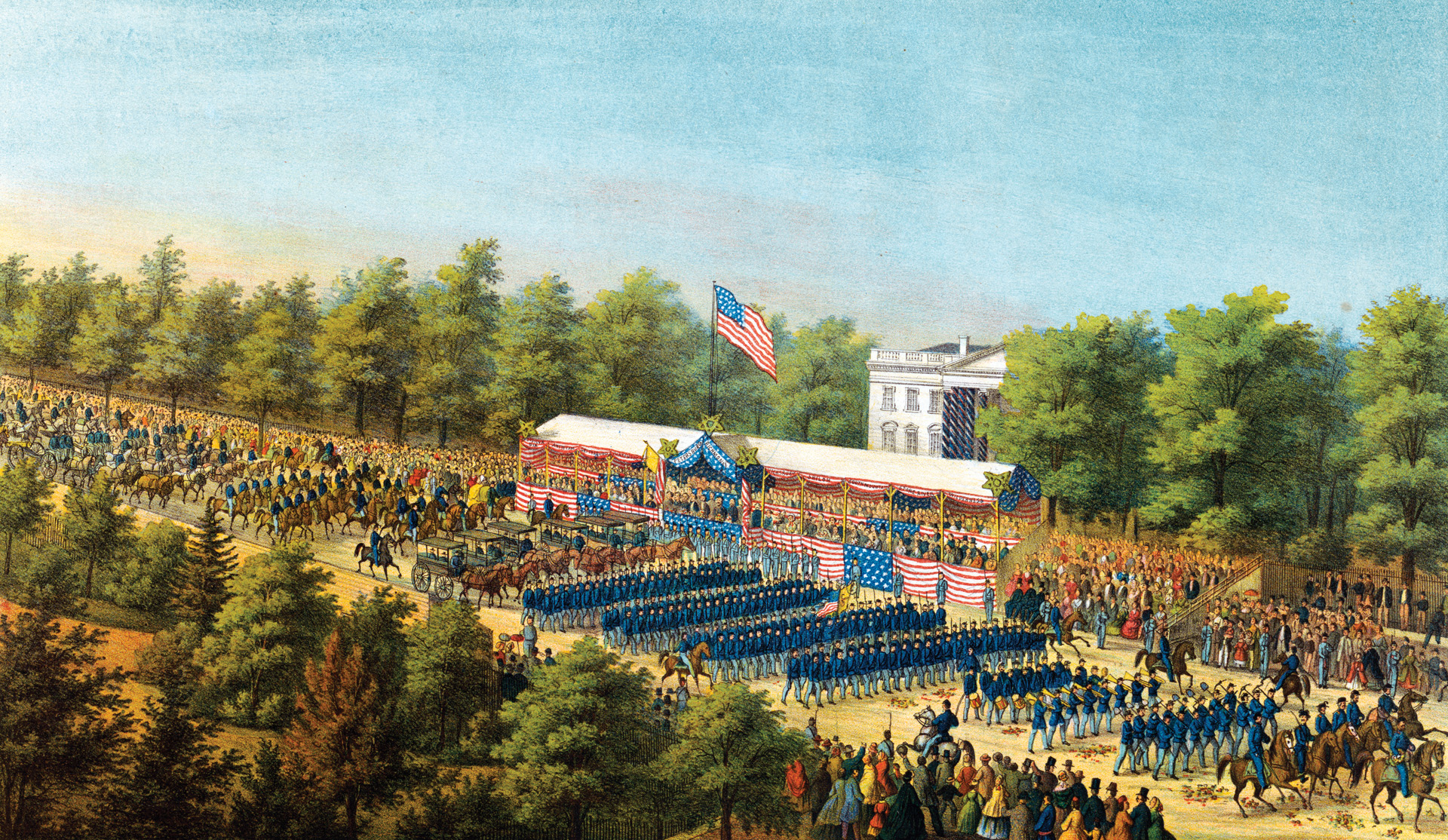

Opposite the White House, planners erected a roofed review stand decked out in stars-and-stripes bunting for the president, his cabinet, congressional leaders, generals, and foreign dignitaries. A line of placards running along the front listed the Federals’ great victories. The front row was reserved for the president, his cabinet and Generals Grant and Sherman. Two special reviewing stands were erected by private citizens, including a wealthy Boston financier, one for wounded and sick soldiers, the other for deaf children. A separate stand was also erected across the avenue in Lafayette Square for lesser notables—congressmen, public officials, and members of the press.

State governors found their places elsewhere. Reuben E. Fenton, whose home state of New York had contributed dozens of regiments and suffered nearly 40,000 dead, watched the parade from a balcony of the Metropolitan Hotel. Fenton was not the only governor so exiled from the review stand. A few blocks west at the Hotel Willard waited Governor Andrew Curtin of Pennsylvania, whose state had suffered more than 26,000 killed in the war. As the Army of the Potomac had the honor of marching first, on the first day Sherman sat in the review stand. Joining Sherman were his wife and son Tommy and his frail father-in-law, Senator Thomas Ewing. A line of soldiers stood guard at the base, bayonet tipped rifles at the ready for any sign of trouble.

“Pass, Pass, Ye Proud Brigades”

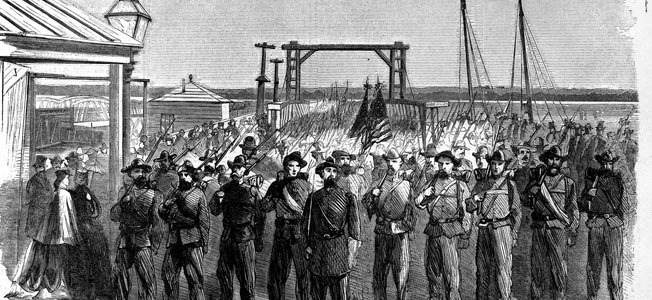

Across the Potomac River in Alexandria encamped the Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. George Meade, the victor of Gettysburg. Meade and his staff meticulously planned the march and issued orders mandating the correct route and order. Meade slated IX Corps to lead the army down Pennsylvania Avenue, followed by II Corps and V Corps. In preparation for the review, IX Corps had marched into Washington the night before, their route taking them toward the city’s famous Long Bridge. After crossing the bridge into the city, the corps had marched up Maryland Avenue and then turned east past Capitol Hill, going into camp 1½ miles east of the Capitol building. Nearby the Union Cavalry Corps also made camp, while just across the river II Corps waited to cross Long Bridge the next day.

At 9 am a cannon shot signaled the beginning of the Grand Review, and the Army of the Potomac began its march west down Pennsylvania Avenue. Walt Whitman was in the crowd near Capitol Hill as the parade began. He captured the moment in his poem, “The Heroes Return”: “Pass, pass, ye proud brigades, with your tramping sinewy legs,/With your shoulders young and strong, with your knapsacks and your muskets;/How elate I stood and watch’d you, where starting off you march’d.” Whitman was particularly eager to catch a sight of his brother, George Washington Whitman, who was marching in the ranks of the 51st New York Infantry.

The army’s ranks were filled mostly by men from the East, although some Midwestern regiments were also in the Review. Soldiers from the farms of Pennsylvania joined Connecticut factory workers and clerks from the tree-lined boulevards of Massachusetts. These were regiments that had endured defeat after defeat on the Virginia Peninsula, at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, only to keep going back into battle again and again. Even their victories were hard won—bloodbaths at the Wilderness and wearying trench warfare at Petersburg. For all their hardship, they remained spit-and-polish soldiers, splendid in shined boots, gleaming belt buckles, and forward-sloping kepis. Behind each infantry brigade came six mule-drawn army ambulances, their bloodstained stretchers strapped to their sides in graphic, if mute, recognition of the human cost underlying the Union triumph being celebrated that day.

Since they would not march until the next day, many thousands of men from Sherman’s army were in the crowd as the Army of the Potomac passed in review. One such soldier was Private Theodore Upson of the 100th Indiana Regiment. Upson was a farm boy who had enlisted in 1862 and had seen action in many of the great battles of the war. He and the 100th Indiana marched all the way from Atlanta through the Carolinas to Washington. He pronounced himself impressed with the easterners. “Their marching was machine like,” he wrote. “They carried their guns most of the time at ‘Shoulder Arms,’ their officers were dressed in their finest uniforms, and their non-commissioned officers had their swords which our boys soon got tired of and long since discarded.”

The March Down Pennsylvania Avenue

Meade and his retinue proceeded first down Pennsylvania Avenue, riding before a marching band. Riding his favorite mount, Blackie, Meade was greeted by thunderous cries of “Gettysburg! Gettysburg!” For reasons never explained by either Grant or Johnson, both were absent from the review stand as the parade began. Although they missed the beginning, the commanding general and the commander-in-chief arrived in time to see the Army of the Potomac’s rank and file pass before them. Also present was Grant’s wife, Julia, and their young son Jesse, sitting on his father’s lap.

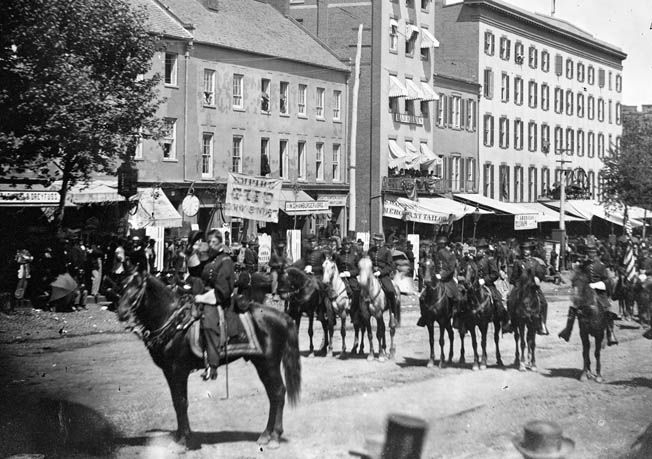

As it had done in battle, the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps led the march. Whitman had encountered the cavalry the day before, describing them as “superb-looking fellows, brown, spare, keen, with well-worn clothing, many with pieces of waterproof cloth around their shoulders, hanging down. They dash’d along pretty fast, in wide close ranks, all spatter’d with mud; no holiday soldiers; brigade after brigade.” Their commanding general, Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan was down in Texas, showing the flag against French forces in Mexico, who had occupied the country since 1861. On review the corps was led by Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt. He had commanded a brigade at Gettysburg and later the 1st Cavalry Division in Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley campaign.

Brevet Maj. Gen. George Armstrong Custer, a born showman if there ever was one, led his 3rd Cavalry Division in the forefront of the march. Custer and his horse were national celebrities, easily identifiable as they rode down Pennsylvania Avenue. Onlookers shouted the many battles in which Custer had defeated the Rebels, places like Winchester, Cedar Creek, and Gettysburg. Before the reviewing stand, a woman threw an evergreen wreath in front of Don Juan. Panicking, the horse galloped full-tilt toward the president and other dignitaries. It was a moment of high drama, but Custer drew great applause when he brought the frightened horse under control and casually resumed the march. (Some thought the incident had been contrived to attract even more attention to Custer.)

A Controversial Surrender

Meade dismounted in front of the presidential reviewing stand, saluted the president and other dignitaries, and took a seat beside Sherman while the army continued past. “I’m afraid my poor tatterdemalion corps will make a poor appearance tomorrow, when contrasted with yours,” Sherman whispered to Meade. “People will make allowances,” Meade replied airily. Sherman later wrote generously of the Army of the Potomac’s passing, “The day was beautiful, and the pageant was superb.” As he watched the Army of the Potomac pass in review, Sherman was a relieved and satisfied man, sensing that the controversy that had dogged him for weeks was finally past. After Grant accepted Lee’s surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, Sherman accepted the surrender of Joseph E. Johnston and the Army of Tennessee. In negotiations with Johnston, Sherman had been incredibly lenient, allowing Confederate forces to keep their arms and insisting only that the existing Confederate state government swear an oath of allegiance to the Federal government. Sherman’s terms also guaranteed the rights and property of Confederates, which Radical Republicans thought could be interpreted as allowing Confederates to keep their slaves.

Timing was everything. Sherman finished negotiating with Johnston and forwarded the agreed on terms to Washington for approval. The previous two days had seen Lincoln’s funeral and procession through the streets of Washington. News of Johnston’s surrender arrived at the White House when the wound of Lincoln’s assassination was still fresh and raw. Andrew Johnson and the cabinet immediately rejected Sherman’s terms. Stanton, for his part, was outraged at the agreement and accused Sherman of treason. Grant defended Sherman’s motives, though not the terms. After a furious cabinet meeting, he set out for North Carolina to confer with Sherman. The next day Sherman’s agreement was leaked to the press, which was itself outraged. Stanton took to the press as well, publicly rebuking Sherman with a signed statement published in the New York Times and the Chicago Tribune. Upon arriving at Sherman’s headquarters in Raleigh, Grant informed his friend of the political firestorm he had triggered. Duly chastened, Sherman reluctantly informed Johnston that Washington had rejected the agreement and demanded harsh terms similar to those that Lee accepted at Appomattox.

Much to Sherman’s displeasure, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, now commanding the Virginia Department, was also publicly critical of the surrender, ordering his own forces to enter territory occupied by Sherman and instructing his generals to ignore any orders from Sherman. Later, when Sherman was marching through the Department of Virginia, Halleck invited him and his staff to stay at his headquarters at Fortress Monroe. Sherman curtly replied, “After your dispatch to the Secretary of War of April 26th I cannot have any friendly intercourse with you. I will come to City Point tomorrow and march with my troops and I prefer we should not meet.” Embittered, Sherman marched on for Washington with the army he loved.

Congress got in on the act and scheduled hearings on the matter. The hearings fell under the jurisdiction of the Committee on the Conduct of the War, chaired by Stanton ally and leading Republican Radical Senator Benjamin Wade. Ironically, like Sherman, Wade was an Ohio man, and represented the state in the Senate alongside the general’s younger brother, John Sherman. When Sherman appeared before the committee on May 22, he was livid with Stanton but kept his famous ire in check. In his testimony before the committee, Sherman described his negotiations with Johnston and his thinking behind the terms he had granted. He was mildly critical of Stanton, saying he felt “hurt and annoyed” by the secretary’s actions. To Halleck, Sherman showed no mercy. “The plan of cutting [Johnston’s] retreat is hardly worthy of one of his military education and genius,” he said. As for the matter of the initial surrender document, Sherman took the blame himself for the lenient terms rather than fob it off on the deceased president. When the congressional grilling shifted to the meeting between Lincoln, Grant, Sherman, and Admiral Horace Porter at City Point, Sherman simply replied, “Nothing definite, it was simply a matter of general conversation, nothing specific and definite.”

The controversy passed, but Sherman remained bitter toward both Halleck and Stanton. Grant told him to prepare his troops for the Grand Review. “I will be ready by Wednesday though on the rough,” Sherman responded. “Troops have not been paid and clothing is bad but a better sort of arms and legs cannot be displayed on the continent.” On the night of the 23rd, Sherman planned his army’s march down Pennsylvania Avenue. He realized that his western men could never match the Army of the Potomac’s polish—they were just not those kinds of soldiers. Walt Whitman, too, thought the westerners a different breed. “These Western soldiers are more slow in their movements, and in their intellectual quality also; have no extreme alertness,” he wrote. “They are larger in size, have a more serious physiognomy, are continually looking at you as they pass in the street. They are largely animal, and handsomely so.” He admiringly described them in a poem: “No holiday soldiers—youthful, yet veterans,/Worn, swart, handsome, strong, of the stock of homestead and workshop,/Harden’d of many a long campaign and sweaty march,/Inured on many a hard-fought bloody field.”

Sherman’s March Through Washington

Rather than present a parade ground army, Sherman chose to present his men as they had appeared marching through Georgia and the Carolinas. As they marched down Pennsylvania Avenue, Sherman’s infamous bummers preceded each division; a half dozen ambulances brought up the rear. Interspersed between each division marched Sherman’s African American pioneer battalions, striding in perfect cadence and holding their axes and spades in place of rifles, their own weapons of war instrumental in defeating the Confederacy. A particular crowd favorite was Brig. Gen. H.A. Barnum of Syracuse, New York. Now commanding the 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, XX Corps, Barnum had been wounded and left for dead in his very first battle. Recovering, he had fought four more battles before being wounded again. In Washington for the Review, he brought with him 35 enemy flags his men had captured. Loud cheers greeted his stalwart appearance.

In stark contrast to the eastern men, Sherman’s men sported the same tattered uniforms they had worn during the March to the Sea and through the Carolinas. Some of the men had obtained new uniforms in Goldsboro, North Carolina, but most refused to wear them—their old uniforms were good enough for them. “Their uniforms looked dingy as if the smoke of numberless battlefields had dyed their garments, and the soil of the insurrectionary states had adhered to them,” noted Sergeant Rice C. Bull of the 123rd New York. Instead of the formal kepis of the Army of the Potomac, the men of the west wore broad-brimmed slouch hats atop their heads. Many were barefoot and insisted on remaining so. The night before the War Department delivered fresh uniforms to the army encampment across the river. The western men rejected them, at least on parade. Of the army’s impending march, Private Upson thought, “I knew it would not be such a glittering pageant, for our Army is to march as they have been marching—just as we come from the front without any extra fuss or feathers.” After watching the Army of the Potomac, Upson and his friends came back over the Long Bridge, changed, and went into Washington for a night of revelry. Upson’s commanding officer reminded the Indiana men that they were still soldiers in the United States Army and warned, “Remember I have not discharged you yet.”

With many of the rank and file no doubt suffering hangovers and sleep deprivation, Sherman’s army set off down Pennsylvania Avenue promptly at 9 am. The Army of the Tennessee led the review, each man marching with his blanket roll over his right shoulder and two days’ worth of cooked rations in a haversack on his left hip. At the head of the army came its commanding officer, one-armed Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard. Howard was destined for great things after the war. He had lost an arm at the Battle of Seven Pines in June 1862. After the Review, he would chair the Freedman’s Bureau and later help found Howard University for the training of black divinity students.

“The streets were filled with people to see the pageant,” Upson wrote, “armed with bouquets of flowers for their favorite regiments or heroes, and ever thing was propitious. My how they cheered! It was a constant roar.” The men of the West were indeed a great curiosity to the throngs lining Pennsylvania Avenue, most of whom had never ventured beyond the Appalachians. The refined young ladies of Washington were intrigued; they had never seen men such as these. Rugged and tanned, the sons of western pioneers came back east as weathered, conquering heroes.

Upson marched down Pennsylvania Avenue with his fellow Indianan, Colonel Benjamin Harrison, commander of the 70th Indiana Regiment, great-grandson of a signer of the Declaration of Independence, grandson of a former president, and future president himself. Also in Sherman’s army was another future president, Major William McKinley of the 23rd Ohio Regiment. Still other future presidents on the reviewing stand included Maj. Gens. Rutherford B. Hayes and James A. Garfield. Like their wartime commander-in-chief, Abraham Lincoln, Garfield and McKinley would both be assassinated during their presidencies.

Upon reaching the review stand, a teary-eyed Sherman turned in the saddle and viewed his victorious army marching down Pennsylvania Avenue. “The sight was simply magnificent,” he wrote. “The column was compact, and the glittering muskets looked like a solid mass of steel, moving with the regularity of a pendulum.” As he passed the reviewing stand, Sherman held his sword high in salute to the president. Before Sherman reached the reviewing stand he had ridden past the Lafayette Square home of Secretary of State William Seward, still recovering from wounds suffered in his assassination attempt. As a mark of debt and respect, Sherman had tipped his cap to the wounded secretary, who returned the gesture from his bedroom window.

Sherman Snubs Stanton

As Meade had done the previous day, Sherman dismounted and took his place among the honored guests. There ensued a moment of high political drama. Sherman walked up the stand toward his wife and father-in-law. On the way he shook hands with President Johnson, Grant, and every cabinet member he saw. Sherman wrote with satisfaction, “As I approached Mr. Stanton, he offered me his hand, but I declined it publicly, and that fact was universally noticed.” A hushed murmur spread through the stands. Sherman’s trusted aide, Colonel Henry Hitchcock, was looking for a seat and did not see Sherman’s snub of Stanton, but conceded that “the incident was plainly seen by many even across the Avenue with their opera glasses. I heard of it a few minutes later.”

After passing the White House, Sherman’s army retraced its steps, heading southwest down Maryland Avenue and back across the Long Bridge. From there the army encamped a few miles down the Potomac at Crystal Springs, where Sherman began the last roll call of the Army of the West. On May 30, he issued Special Field Order No. 76, the last such order he would issue to his army: “The general commanding announces to the armies of the Tennessee and Georgia that the time has come for us to part.” He briefly recounted and praised the army’s exploits, attributing their combined victories to hard work and discipline. Sherman warmly concluded, “Your general now bids you farewell, with the full belief that as in war you have been good soldiers, so in peace you will make good citizens.”

“They Marched Like Lords of the World”

By then the rank and file were anxious to be mustered out and sent home. As the 100th Indiana mustered out of the Army, Theodore Upson was told that even after he returned to Indiana he remained under orders and was to report to his commanding officer via mail every 60 days. For his trouble he would receive 30 days’ pay. The Indiana men traveled in boxcars through Pittsburgh and then boarded boats that took them along the Ohio River. Landing at Lawrenceburg, they entrained for Indianapolis, where a great assembly of citizens awaited their return. Upson married and fathered six children, becoming a prosperous carriage manufacturer and a well thought of member of his community. He served as commander of the local post of the Grand Army of the Republic and lived to see the next great American army, the Doughboys of the American Expeditionary Force, march off to war in 1917.

In all, some 342 infantry regiments, 27 cavalry regiments, and 44 artillery batteries, along with assorted engineers, signal corpsmen, ambulance drivers, provost marshals, and black civilian pioneers, had tramped past the reviewing stands during the Grand Review. Such an army, marveled the Prussian ambassador, could conquer the world. Perhaps not, but it had certainly conquered the Confederacy and captured the hearts of Northern patriots everywhere. “They marched like lords of the world,” former Ohio Senator Tom Corwin said. No one in the crowd during those two gala days in Washington would have deigned to disagree with him.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments