By Stuart W. Sanders

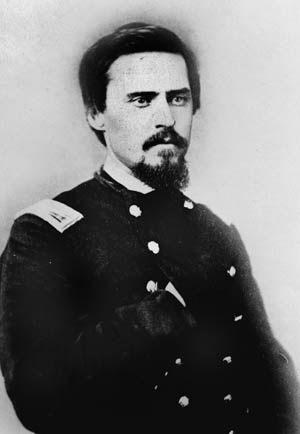

When the Civil War erupted, so many of Lisbon, Ohio-born Robert McCook’s large extended family joined the Union Army that the clan became known as the “Fighting McCooks.” Nine brothers, his father, uncle, and five cousins all entered Federal service. Many of them would not live to see the end of the war.

“I Know the Germans Will Fight”

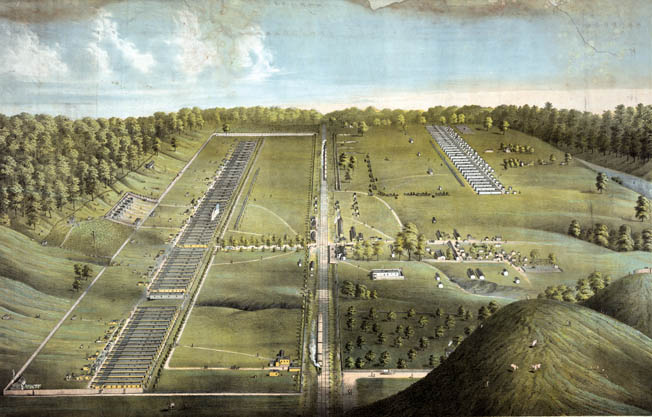

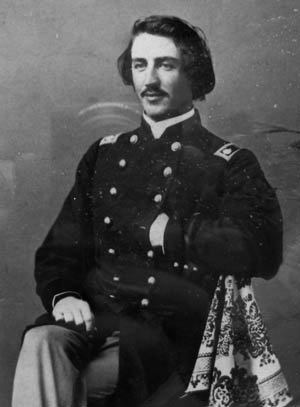

Having opened a law practice in Cincinnati, 33-year-old Robert McCook became colonel of the 9th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The regiment was composed mainly of German residents of the Queen City, many of whom had seen prior service in European wars. McCook had specifically wanted to command an all-German regiment, stating, “I know the Germans will fight. Our American boys mean well enough, but they don’t know how.” On April 22, 1861, 10 companies of the 9th Ohio were enrolled for three months’ service. With no uniforms available at the time, McCook wore civilian clothes, a stovepipe hat, and a sword. When the regiment reached Camp Dennison near Cincinnati for training, members learned that President Abraham Lincoln had called for three-year enlistments. A majority of the men, including their commander, immediately extended their service.

An examination of the early regimental rolls shows that of the 11 officers in the regiment, nine were German. In addition, of the 10 companies that enlisted in 1861, the majority of the members were recent immigrants. Names like Gebhard Krug (Company B) and Sebastian Hienrich (Company E) were the norm, while men like Henry W. Sanders (Company E) and Charles Boyle (regimental surgeon) proved the exception. According to the unit’s regimental history, 57 members were born in the United States, 1,012 were born in Germany, 56 in Switzerland, 25 in France, three in Russia, one in Holland, and one was born at sea. Although most were recent immigrants, one 19th-century historian noted, “No regiment is more justly entitled to the thanks of the patriotic people of Ohio for distinguished services in support of the Union and the flag than the 9th [Ohio] Infantry.”

Luckily for the English-speaking McCook, German-born Lieutenant August Willich handled regimental drill. So competent was Willich that many Union officers believed that the 9th Ohio was the best-drilled Union regiment in the army at that time. McCook modestly did not take credit for the men’s discipline. One soldier wrote that “McCook, who humorously exaggerated his own lack of military knowledge, used to say that he was only ‘clerk for a thousand Dutchmen,’ so completely did the care of equipping and providing for his regiment engross his time and labor.” The self-described clerk soon found himself in combat.

“With the Order and Steadiness of Veterans”

On September 10, McCook led a brigade consisting of the 9th Ohio and 13th Massachusetts near Carnifex Ferry in western Virginia. Although the 9th skirmished with Southern troops and was ordered to storm Confederate entrenchments, nightfall prevented the Ohioans from further engaging the enemy. One month later, McCook’s men battled near Harpers Ferry. On October 8, the 13th Massachusetts crossed the Potomac River and moved to capture Confederate wheat supplies. Although the grain was secured, Southern troops under Colonel Turner Ashby drove Federal pickets off Bolivar Heights, 2½ miles from Harpers Ferry. The Confederates charged the town of Bolivar but were repulsed after sustaining 10 casualties. Union troops held the heights until midnight then crossed back into Maryland, suffering four killed, seven wounded, and two captured. Another Federal officer remarked that McCook, “as an amateur soldier, gun in hand, volunteered and rendered much service during the engagement.”

Early the next year, McCook commanded a brigade in Kentucky under Brig. Gen. George H. Thomas that included the 9th Ohio and the 2nd Minnesota Regiments. Confederate General Felix Zollicoffer had occupied Mill Springs in southern Kentucky. The Confederate commander made a tactical error by placing his troops’ backs to the swollen Cumberland River. Confederate Maj. Gen. George Crittenden disapproved of the strategy and took command but had no time to fix Zollicoffer’s blunder. Thomas’s troops were approaching. A cornered Crittenden decided to attack.

Crittenden’s lead regiments encountered the 10th Indiana and 4th Kentucky Union Infantry Regiments. As the Confederates deployed on the enemy left, the Federal soldiers began to run low on ammunition. McCook’s two regiments were soon ordered to the front. Forming on the Mill Springs Road, McCook briefly stopped to speak with the commander of the 10th Indiana. He learned that the enemy was in force on the top of the next hill beyond the woods and that they had forced the 10th Indiana to retire. McCook ordered his brigade forward.

McCook’s men advanced, he said, “with the order and steadiness of veterans.” The Confederates shouted and pressed forward. McCook deployed his brigade, placing the 2nd Minnesota on the left of the road and the 9th Ohio in a cornfield on the right. He then engaged the enemy. As the Federals pressed forward, gunfire erupted and McCook was shot through the right leg below the knee. Three other balls passed through his horse and another through his overcoat. McCook, dismounted, refused to leave his command.

With their commander limping forward at the head of the brigade, the 2nd Minnesota found their right flank 10 feet from the Confederate line. The 9th Ohio also pressed the enemy, who were positioned behind hay bales and fence rails. When the Union left closed with the Confederates, the contest became hand to hand. The troops battled at close quarters for half an hour, and the Confederate line wavered. McCook saw an opportunity and ordered the Ohio regiment to charge. Thomas reported that “the Ninth Ohio charged the enemy on the right with bayonets fixed, turned their flank, and drove them from the field, the whole line giving way and retreating in the utmost disorder and confusion.” McCook’s German regiment broke the enemy line and drove the Confederates from the field.

Drummer boy William Bircher of the 2nd Minnesota recalled the rout. “Our regiment charged up to a rail fence, and here occurred a hand-to-hand conflict: the Rebels putting their guns through the fence from one side and our boys from the other,” he wrote. “The smoke hung so close to the ground on account of the rain that it was impossible to see each other at times. The Ninth Ohio then made a charge along the Rebel left flank and drove them from their front. Then followed one of the worst stampedes, I think, that occurred during the war.”

The Confederates, many of whom carried antiquated flintlocks, were routed. Hastening their defeat was the death of General Zollicoffer. As the fighting reached a crescendo, Zollicoffer accidentally wandered into enemy lines and was shot dead. Although Crittenden attempted to rally his men, the 9th Ohio’s bayonet charge pushed the defenders from the field. At Mill Springs, the Federals lost 39 killed and 207 wounded. The Southerners suffered 125 killed, 309 wounded, and nearly 100 captured.

McCook’s brigade suffered 55 casualties, and his men took great pains to care for the wounded. According to one Union soldier, “Some of the 9th Ohio carried their wounded comrades nine miles to avoid jolting them over the rough roads.” Although seriously injured, McCook remained on duty until his brigade returned to camp. On January 28, the Ohio General Assembly passed a resolution thanking Thomas, McCook, and Colonel James A. Garfield for their successes in the Bluegrass State. Colonel Mahlon D. Manson of the 10th Indiana remarked, “I shall ever remember with feeling of gratitude and admiration for the prompt manner in which [McCook] sustained me in the hour of trial.” Had McCook not arrived at the field on time, it is likely that Manson’s 10th Indiana would have been decimated. For his service at Mill Springs, McCook was promoted to brigadier general.

Ambushed by Guerrillas

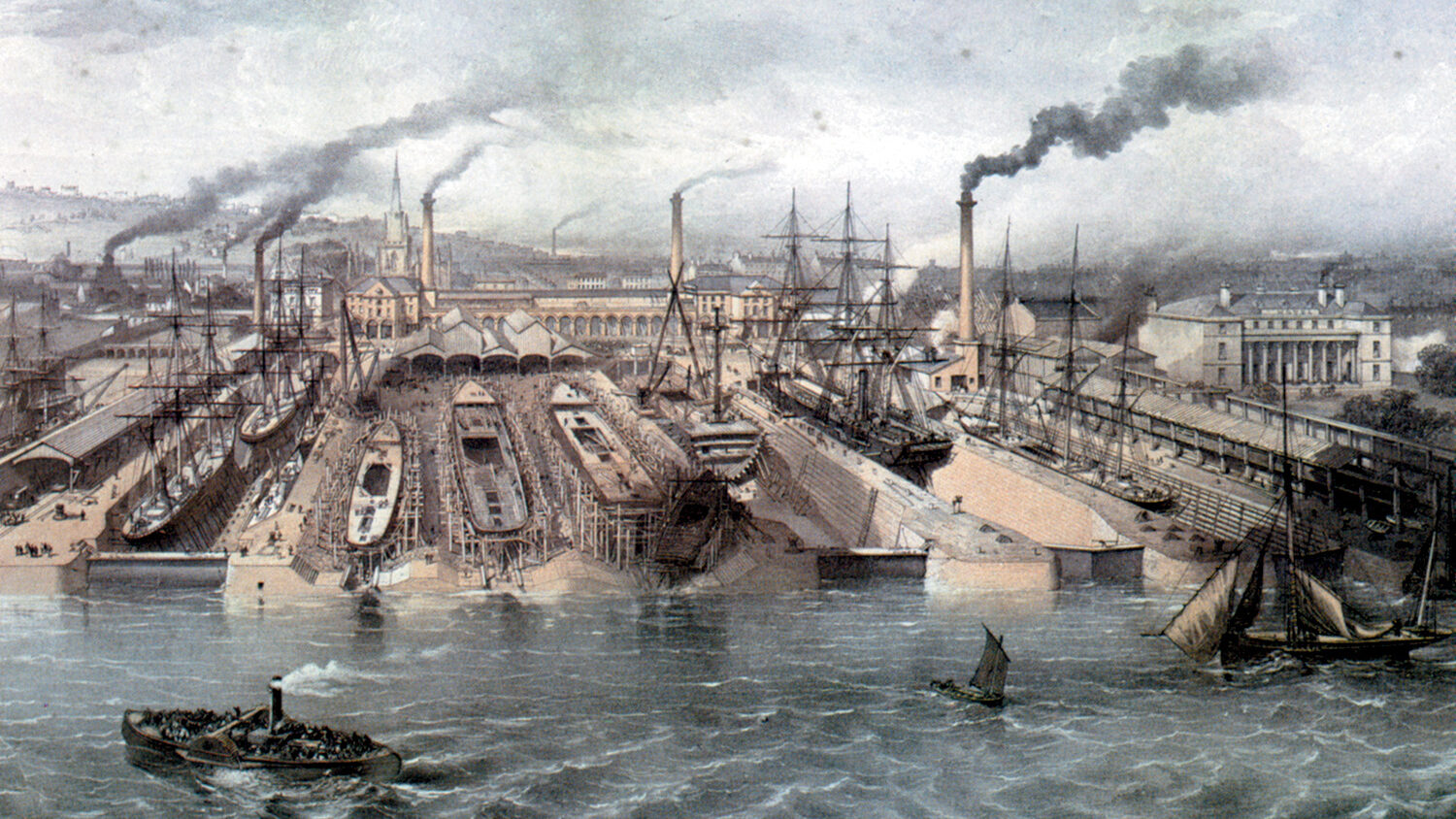

Following the Battle of Shiloh, in which McCook’s men did not take part, the Union Army of the Ohio, led by Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, began a slow trek toward Chattanooga in the hope of capturing the important railroad center. The Federals believed that their advance would cause Unionist elements in East Tennessee to rally to the Stars and Stripes, while hindering Confederate attempts to secure coal, saltpeter, and lead.

During the advance, Confederate guerrillas in northern Alabama and southern Tennessee continually harassed Buell’s army. On May 19, Union Maj. Gen. Ormsby Mitchel informed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that “the most terrible outrages—robberies, rapes, arsons, and plundering—are being committed by lawless brigands and vagabonds.” Mitchel wanted to hang any captured guerrillas. Three days later, he was allowed to execute anyone who participated in “irregular or guerrilla warfare.”

In late July, Thomas established his headquarters at Decherd, Tennessee. On August 1, McCook was ordered to follow the road taken by the cavalry and artillery to Decherd, “where you will encamp your brigade and await the orders of the general commanding.” It was the last order McCook would ever receive.

While on the way to Decherd, McCook rode three miles ahead of his brigade with a staff member, an officer from the 35th Ohio Infantry, and an escort of nine men. McCook was ill—likely with dysentery—and traveled in an ambulance, riding uncomfortably in a bed in an open carriage. At noon on August 5, the command neared New Market, Alabama. When McCook stopped at a house to ask about water and potential campsites, his escort divided. Two men, accompanied by a citizen on an escort’s horse, traveled a half-mile to the rear. Three others rode ahead to find a campsite, while four remained with McCook. One was dismounted, having loaned his horse to the citizen, while another was unarmed and was tending to the sick commander.

As the four men waited near the house, shots echoed from some nearby woods. Suddenly, the men were attacked by a band of 100 to 200 mounted guerrillas. The horsemen stormed toward them, and McCook ordered the ambulance turned around. The wagon’s horses ran away at top speed, but the guerrillas quickly surrounded the party, firing their pistols and yelling, “Stop! Stop!”

McCook rose on his bed, shouting, “Don’t shoot; the horses are running; we will stop as soon as possible.” A guerrilla struck one member of the escort in the head with a saber. Another horseman fired into the ambulance. One bullet pierced McCook’s hat, a second struck him in the side. The shot had passed through his body from the rear, coming out near the buckle of his sword belt. McCook had been gravely wounded.

Finally the ambulance stopped. As the wagon rolled to a halt, a guerrilla rode up with a cocked pistol in hand. McCook simply told him that there was no point in firing because he was fatally wounded already. Two of McCook’s escort, including Captain Hunter Brooke, carried the general into a nearby home. The residents initially wanted to move the officer into the slave quarters because they feared their home would be burned in retaliation if McCook died there. However, McCook remained in the residence thanks to the insistence of Brooke and the other officers.

Once McCook was moved, the raiders put the wagons to the torch, secured all horses and mules, and took the four members of the escort as prisoners. The Confederates also captured an engraved sword with a solid silver scabbard. The inscription on the blade revealed that the U.S. Congress had given it to McCook, likely in thanks for his role in the Mill Springs victory. The sword was returned to McCook’s family after the war.

“The Problem of Life Will Soon be Solved For Me”

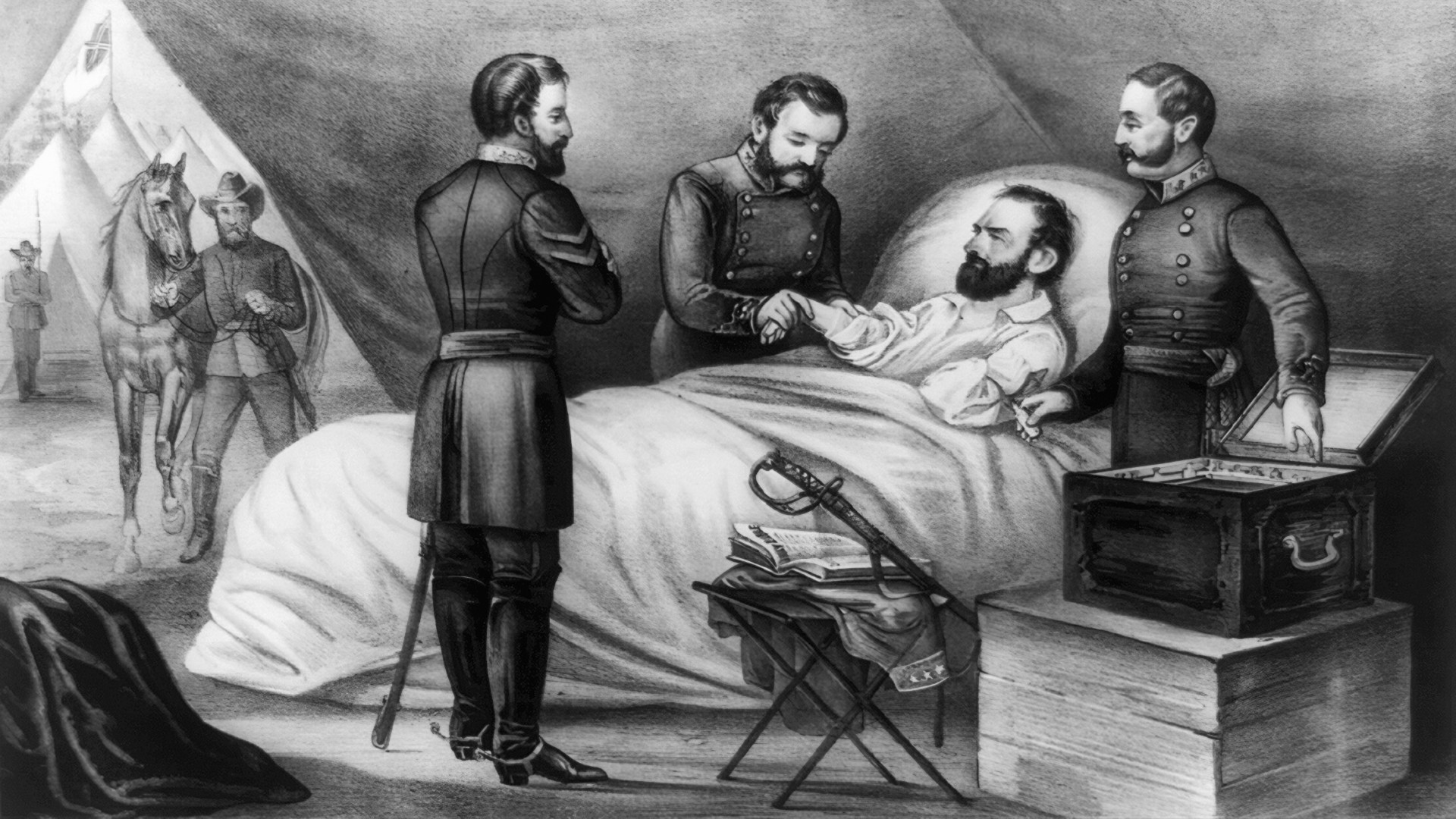

When a subsequent party of Union soldiers found McCook, two surgeons examined the wound and admitted that it was fatal. According to a graphic report in the Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, “The wound was in the bowels, a single ball entering the left side and coming out between the ninth and tenth ribs. When the physicians arrived, General McCook was vomiting blood. He was cool and calm to the last, but suffered greatly.”

McCook took the news calmly, telling one of his subordinates, Captain Andrew Burt, “Andy, the problem of life will soon be solved for me.” When asked if he had a message for his brother, Union Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook, Robert replied, “Tell him and the rest I have tried to live as a man, and die attempting to do my duty.” Later he told Burt, “My good boy, may your life be longer, and to a better purpose, than mine.”

McCook asked another officer to draw up his will. He left his two favorite horses to his brothers Alex and Daniel and gave the rest of his property to his mother. Immediately before his death, McCook clasped the hand of the brigade wagon master and exclaimed, “I am done with life; yes, this ends it all. You and I part now, but the loss of ten thousand such lives as yours and mine would be nothing if their sacrifice would but save such a government as ours.” McCook died at midnight on August 6.

The Vengeance of McCook’s Brigade

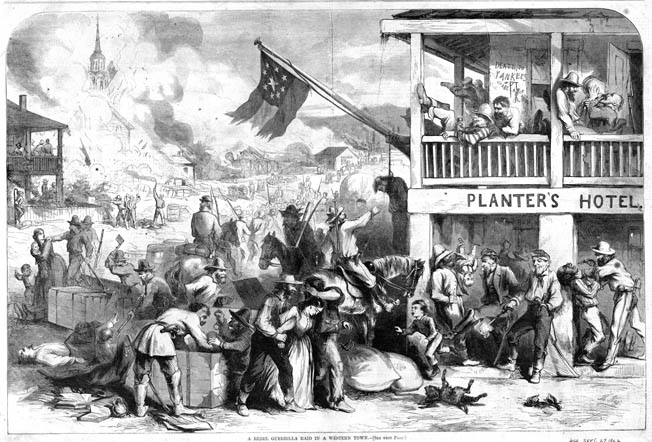

McCook’s brigade was outraged by the attack and quickly took revenge on unoffending local civilians. On August 8, the Nashville Daily Union reported that one of McCook’s regiments went to a nearby plantation “and demolished everything on his premises. We learn they also wreaked their fury on the heads of the rebels in the vicinity.” The vengeful Federals burned private property and shot a Confederate lieutenant who was on furlough and who supposedly had been connected with the men who killed McCook.

The 9th Ohio was particularly vengeful. Not only did they destroy property, they also hanged several people they suspected were involved in the attack. On August 9, the New York Herald reported that “the Ninth Ohio, McCook’s own regiment, on learning of the assassination, marched back to the scene of the occurrence, burned every house in the neighborhood and laid waste to the lands. Several men who were implicated in the murder were taken out and hung to trees by the infuriated soldiery.” Union Colonel John Beatty confirmed the report, noting, “When the Dutchmen of his old regiment learned of the unfortunate occurrence they became uncontrollable, and destroyed the buildings and property on five plantations near the scene of the murder.”

Even the family who had housed the dying officer faced the wrath of angry Federal soldiers. According to one witness, “After General McCook’s death, which was in twenty-four hours, the entire premises of those who had sheltered him were burned, and a sick man, seventy-five years old, with the ladies and children of his family, was made homeless.” Their earlier fears had been realized.

The quest for vengeance continued. One member of the 19th Illinois Infantry killed the horse of an Athens tavern keeper who supposedly had refused to give McCook shelter when the officer was ill. Other soldiers burned portions of Athens, which 15 months earlier had suffered even worse destruction at the hands of Union Colonel John B. Turchin’s brigade. During the earlier incident, the Russian-born Turchin, angry at the townspeople’s resistance to Union troops, had told his men in heavily accented English, “I shut mine eyes for von hour.” The men got the message; an orgy of looting, burning, and pillaging ensued. Now, after several hours of similar destuction, Federal officers succeeded in getting the men under control. Thomas, who hoped to prevent further outrages, implored, “Let us be steady in our efforts to maintain such discipline as will insure to our arms a just retribution upon the dastardly foe who could take advantage of his defenseless condition.” Thomas then ordered the division to wear a badge of mourning for 30 days.

The Controversy of McCook’s Murder

Union troops in other commands were also shocked by McCook’s death, and it shook many soldiers out of supporting any policy that was conciliatory toward the enemy. A member of the 29th Indiana Infantry wrote home, “It must be a very forgiving spirit that will see such work and not swear to take no more prisoners. The time for milk and water manner of doing business is past.” According to the Ohio State Journal, when Robert’s younger brother, Dan, learned of the attack, he swore, “I’ll never take another rebel prisoner as long as God gives me breath.” At the time of Robert’s death, Dan was colonel of the 52nd Ohio Infantry Regiment. He would also die during the war, succumbing to wounds at Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia, on July 17, 1864, one day after receiving his promotion to brigadier general.

Inaccurate press reports and rumors that swirled around the Union camps generated much of the anger in the ranks. On August 8, Robert S. Dilworth of the 21st Ohio Infantry wrote, “Col. McCook of late acting brig gen was shot on his way to Huntsville. He was in the ambulance and the division sutlers train was with him. He was sick and on his way to Huntsville to put up until he would be able to join his command. The secesh took him out of the ambulance & shot him and the sutler in the leg.”

The public was also inflamed by dozens of inaccurate press reports. On August 9, the New York Herald reported, “The rebel guerrillas in the West have inaugurated the course which might fairly be expected from them, in the cowardly and cold blooded murder of General Robert McCook, of Ohio, while journeying sick in an ambulance near Salem, Ala., to join his brigade. The marauders surrounded the ambulance, overturned it, throwing the wounded and helpless officer to the ground, and there butchered him.”

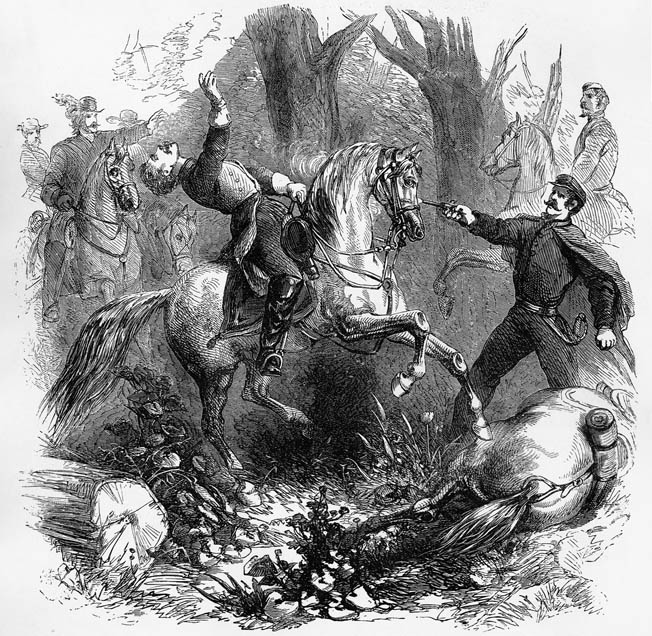

The August 23, edition of Harper’s Weekly also fanned the flames of controversy. This magazine presented a drawing to the public that depicted the “murder” of McCook. Surrounded by overturned wagons and heavily bearded Confederate ruffians, the engraving showed the Northern public that the Union officer did not have a chance. As mounted partisans surround the chaotic scene, their sabers drawn, a stern-visaged bushwhacker fires a rifle into McCook from a few feet away. Held on his knees by the Confederates, the uniformed McCook clutches his chest, throws his head back, and dies. Southern newspapers placed their own spin on the event. The Charleston Mercury stated that the Confederates, who were ambushed by McCook’s party, turned and attacked. McCook, the Mercury noted, “was riding erect, and apparently in fine health, in a carriage stolen from a citizen of North Alabama” when he was killed.

Although many believed the attackers to be bushwhackers, loosely aligned with the Southern service, Captain Hunter Brooke, captured by the raiders, related that the horsemen were regular Confederate soldiers. Brooke sent a note to the colonel of the 35th Indiana after Robert’s death. He wrote that he was the prisoner of a Captain J.M. Hambrick, who wanted to exchange Brooke for his brother, who was a prisoner in Huntsville. Although the fate of Hambrick’s brother is unknown, Brooke was eventually released.

Who Fired the Fatal Shot?

Federal officers who respected McCook did not quickly forget that he had been shot down in his ambulance. On October 23, Brig. Gen. George Crook wrote to future president James A. Garfield that a scouting party “last night caught the notorious Captain [Frank B.] Gurley and his brother, a lieutenant, who murdered General McCook.” For several months, Federal authorities had believed that Gurley was McCook’s killer, although a Confederate at the scene claimed that “as three or four were firing at this party when the General fell, it will always be a matter of doubt as to who fired the fatal shot.” The McCook family, for its part, was certain. Robert’s cousin Edward informed Robert’s brother Alexander, “Watkins last night caught Ragsdale, one of the party with Gurley when Robert was murdered.”

While Federal authorities were initially unsure of Gurley’s role in McCook’s death, the most damning evidence appeared that November. Hunter Brooke, who noted that his own captor was a regular Confederate soldier, testified differently about Gurley. Brooke reported, “A little over a year ago, I can positively swear that [Gurley] was a guerrilla acting without authority from the Confederate government, claiming a partisan ranger without commission and subsisting himself and his band entirely by plunder. He was the murderer of Brigadier General Robert L. McCook, which I well know, as I was present at that sad event and narrowly escaped with my life, being carried away as a prisoner.”

According to J.M. Mann, a Confederate who was also present at the shooting, the chaos of the event made it impossible to determine who fired the fatal shot. “Everything ahead of us was panic stricken,” Mann wrote. “In the lane we overtook a buggy containing the Federal officers. No one could tell who had shot General McCook. Pistol fire is very inaccurate even when men are afoot and near each other. When men are mounted and horses running at full speed and several firing in the same direction, no man can tell whose bullet finds the mark.”

While Mann’s comments cast doubt on Gurley’s role in the incident, Gurley years later may have implicated himself as the shooter. In 1906, a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy presented a paper on McCook’s death. Using Gurley as a source for her research, Annie B. Robertson stated that when attacked, McCook’s wagon turned around and ran into some overhanging limbs, which tore off the top. Gurley and his comrades saw two officers in the back, one in uniform [Brooke] and “the other in his shirt sleeves.” Riding after the wagon, Gurley fired three times at the uniformed officer when he was 50 yards away. One of those bullets struck McCook.

Gurley After the War

Although the capture of Gurley came as good news to Federal commanders, Confederate officials were concerned. On October 21, a scout reported Gurley’s capture. The scout had learned that Gurley, a Tennessee native who had served in the 4th Alabama Cavalry, would be hanged. Gurley, however, escaped the hangman’s noose. As the war drew to a close, Federal authorities determined that McCook’s death was “one of the fortunes of war.” Exchanged in February 1865, Gurley lived after the war on a plantation near Gurley, Alabama and was active in veterans’ affairs.

Gurley’s neighbors viewed him as a “splendid old soldier and leading citizen of North Alabama.” Living in a community named for his ancestors, the formerly condemned man was elected sheriff of Madison County. Although Confederate veterans lauded the supposed killer of Robert McCook, Gurley’s presence irritated the Reconstruction government. At one point, without any official charges being brought against him, Gurley was imprisoned for five months in the Huntsville jail.

Despite harassment by Federal authorities, Gurley remained active in veterans’ affairs and sponsored several barbeques and reunions for Confederate veterans on his farm. During these events, according to one former soldier who knew him after the war, “It was very hard to get the Captain to discuss his General McCook experience, as it appeared to bring up unpleasant memories.” At the 1912 reunion on Gurley’s farm (the seventh such reunion), the veterans passed a resolution in honor of their host. They resolved: “That we hereby extend to him our most grateful appreciation of his heroic services during the war and our keen remembrance of the punishment inflicted upon him after the war by imprisonment, fettered with chains, and a narrow escape from execution by the Federal authorities, all because he participated conspicuously in a fight in which the Federal General McCook was killed.” Eight years later, on March 29, 1920, Gurley died at his home.

Remembering McCook

For their part, the surviving veterans of the 9th Ohio did not forget their slain commander. In the 1870s, artist Leopold Fettweiss sculpted a marble portrait bust of McCook that was dedicated in August 1877. Placed in Cincinnati’s Washington Park, the bust still stands in memory of one more Civil War soldier who had died, as he related, “attempting to do my duty.”

McCook lies buried in Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati. There, 20 McCook graves surround a temple built to honor “the fighting McCooks of Ohio.” The monument, modeled after the Choragic Monument to Lysicrates in Athens, stands more than 17 feet tall and is nine feet in diameter. The structure is surrounded by 12 Corinthian columns, each etched with the name of one of the McCook children.

Buried under the temple is Robert’s father, Daniel, who was mortally wounded while chasing Confederate raider John Hunt Morgan in Ohio. In addition, several of Robert’s brothers also rest there. Alexander, who survived the war and retired as a major general; Daniel, killed at Kennesaw Mountain; Charles, a casualty of First Manassas (Bull Run); Edwin, who was wounded three times during the Civil War yet survived; and Latimer, who also served in the Union Army and lived through the war. Along with the McCook family, 40 other Union generals, including Joseph Hooker, William H. Lytle, and Henry M. Cist (author of the classic study Army of the Cumberland) lie buried at Spring Grove. The cemetery was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments