By Stephen C. Ruder

The Union bid to capture Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1863 was set in motion seven months earlier, in the autumn of 1862. At that point, the war was not going well for the Union, and President Abraham Lincoln was looking for a clear-cut military victory to bolster his domestic political support. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus V. Fox saw an opportunity for the Union Navy to shine by seizing Charleston. The Confederates had fired the first shots of the war there, at Fort Sumter, and Northerners considered the city the cradle of rebellion. Occupying Charleston would be a huge morale boost for the flagging Union war effort.

It was not an outlandish idea. A combined Army-Navy operation had already taken Hilton Head, a short distance south of Charleston, in late 1861 and had essentially closed the port of Savannah with another combined operation a few months earlier. In October 1862, Fox, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, and President Lincoln agreed—Charleston would be the next target. Fox was convinced that the Navy could steal the limelight from the Army at Charleston by using ironclad ships to blast a path into the harbor. He was enamored of the new ironclad warship technology and thought the new craft invulnerable. Multiple hits on ironclads in duels with Confederate gunners at Fort McAllister, near Savannah, in January and March had caused only superficial damage, seeming to prove Fox correct.

With divergent plans in mind, Union ground and naval forces assembled at Hilton Head and spent the winter preparing for the Charleston campaign. The Confederates defending the region knew that they were at an extreme disadvantage. Looking for any means possible to even the odds against the numerically superior Union forces, the Confederates attempted to gain an edge through complex intelligence operations. With enemy troops and ships poised to attack anywhere along the Atlantic coastline, the Confederates needed early warnings from Hilton Head of major Union expeditions. Accordingly, they employed the full spectrum of tactical human intelligence, maintaining a loose cordon of observers in the area and infiltrating at least one spy into the Union ranks to gather information on the island.

The missing piece for the Confederates was signaling intelligence. For several months, they had been trying without success to read Union flag signals. They knew that reading the Union messages would provide the best forewarning that they could possibly achieve. But what were those flag signals, and how did they work?

During the Civil War, both sides used the signal flag or wigwag system developed by Army surgeon Albert J. Myer in 1856. The wigwag system used a single flag moved to the left, right, and center of the signaler. Each series of movements represented a series of numbers which in turn represented a letter, word ending. or phrase. One drawback to the wigwag system was that the enemy was likely to be able to see it. As a result, both sides invested in rudimentary ciphers to counter enemy intelligence. The Union deployed a cipher system centered on a device called the signal or cipher disk. Each Union signal station was equipped with a cipher disk to encrypt and decipher messages. The cipher disk was made of two cardboard disks fastened together. Each time the alignment of the disks was changed, it set a new cipher.

The cipher disk was used within the Union Signal Corps, and instructions demanded that ciphers be changed often. The frequency and method for relaying the changes were left to the senior signal officer in each command. Union signal officers were required to memorize these cipher instructions to ensure that “in case of capture, no information will fall into the hands of the enemy.” For additional security, Union signal officers were advised, “When there is danger of capture, all messages or important papers must be destroyed,” presumably including the cipher disk. Finally, knowledge of the cipher system was restricted to officers. Enlisted Union signalers merely signaled the numbers read to them by their officers.

In order to intercept and read the Union signals, the Confederates defending Charleston needed to understand the Union cipher system. Analyzing intercepted Union messages had not revealed the secrets of the system. So when the Confederates learned of an opportunity to capture a Union signal officer, they decided to take a different approach to the problem.

The Capture of Caleb Jones

Since late 1861, Hilton Head Island had been a Union forward operating base defended by thousands of troops and providing logistical support to the Union Navy blockading fleet. To maintain communications with defenses on the more remote west coast of the island, the Union Army had established a signal station in the Spanish Wells plantation house overlooking Calibogue Sound. Relatively isolated, the signal station was normally manned by two Signal Corps officers and four enlisted signalmen and defended by several infantry companies.

On the night of February 11, 1863, a two-man Confederate reconnaissance patrol crept ashore at Spanish Wells. The patrol remained hidden all the next day, noting the activity, and took Private Caleb Jones of the 9th Maine Volunteers prisoner, leaving that night. Jones, 45, hailed from Brighton, Maine, and had been in the Army for five months. One of his fellow soldiers wrote that Jones “always talks secesh,” suggesting he sympathized with the Confederates. For the next week, Jones was thought to have deserted. Even after his fate became known, Union officers never seriously investigated the circumstances of his capture.

Perhaps spurred by his “secesh” sympathies, Jones appears to have readily provided what proved to be vital intelligence. Before the reconnaissance, the Confederates had apparently seen a platform built on the roof of the Spanish Wells plantation house but thought it was used only for observing the Sound. The prisoner divulged that it was actually a signal station and that the guard force was not allowed inside, suggesting that anyone inside the house was probably a member of the Union Signal Corps. Finally, the ease with which the patrol entered and left the area revealed that the Spanish Wells signal station was poorly guarded. The poorly protected, isolated signal station at Spanish Wells was a tempting target for Confederates desperately seeking information about the Union signaling system.

Raid on Spanish Wells: “The Surprise Was Complete”

Men from E Company of the 11th South Carolina Volunteers, commanded by 33-year-old Captain John H. Mickler, had executed the February reconnaissance to Spanish Wells. They were local men who knew the waterways and back roads like the backs of their hands. Already experienced raiders and intelligence gatherers, in modern terms these men would be considered commandos. In great secrecy, a select group of E Company soldiers, led personally by Mickler, prepared to capture a Union signals officer from the station at Spanish Wells.

Just after midnight on March 13, 1863, the Confederates returned to Spanish Wells in force. The 25-man raiding party silently landed and surrounded the signal station. They quickly entered the building and captured three enlisted signalers. The two signal officers on duty were upstairs. The station commander, 1st Lt. Milton Fenner, and a fourth enlisted signaler escaped out an upstairs window, but 1st Lt. Thomas Rushby rushed downstairs and was captured. As Fenner reported later that day, “The surprise was complete.”

In less than five minutes, the Confederate mission was accomplished without a shot fired. The raiding party set fire to the house and swiftly returned to their boats, scooping up five guards along the way. While it might seem unwise to take so many prisoners, this was likely part of a deception. By taking both signalers and infantry as prisoners, the Confederates’ true target was obscured.

As the raiding party paddled across the Sound with their prisoners, pandemonium broke out in Spanish Wells. Not observing the retreating boats, 9th Maine troops scoured the area around the plantation house looking for the raiders and their prisoners. The light of the house fire alerted a reserve regiment that also entered the area about an hour later. It was to no avail—the raiding party was gone and the prisoners were on their way to the jail in Hardeeville, South Carolina, about 20 miles to the west.

To Trick the Captured Thomas Rushby

At the time of his capture, Manhattan native Thomas Rushby was 27 years old and had nearly two years of military service under his belt. A combat veteran, Rushby was part of the Union expeditionary force that took Hilton Head Island in 1861, captured Fort Pulaski at Savannah in 1862, and fought in the Battle of Secessionville, near Charleston, in June 1862. Promoted to first lieutenant in October 1862 just before his regiment was transferred back to Hilton Head, Rushby volunteered for signal duty and began training that winter. Rushby was one of several officers recruited for signals duty in preparation for the upcoming Charleston campaign. While an experienced combat engineer, Rushby had been a signal officer for only a few months when he was captured.

With the capture of Rushby, the Confederates now needed to extract the signaling system details he had memorized. While the details of their plan are lost to history, it is possible to reconstruct the likely course of events. The Confederates were aware that Rushby would be repatriated within a few weeks, exchanged for a Confederate officer captured by the Union. If they attempted to coerce the information from Rushby, he would report the security breach and the cipher system would be changed as soon as he returned. The only recourse was skullduggery, to trick Rushby into providing the key, without him realizing he had done so.

Unfortunately for Rushby, the Confederates had just brought in an experienced intelligence operative, 33-year-old Captain Edward Pliny Bryan. Within a week of Caleb Jones’s revelations about the signal station at Spanish Wells in February 1863, Confederate leaders in Charleston had made a special request that Bryan be immediately transferred from the Army of Northern Virginia to Charleston. Bryan had previously done intelligence work for several officers now leading the defense of Charleston and the coincidence of his immediate transfer and Jones’s disclosures suggests the Confederate leaders thought Bryan would be integral to the unfolding intelligence operation. By the time Rushby was captured in March 1863, Bryan was probably already in Charleston.

While gathering intelligence along the Potomac River in 1861, a Union patrol captured Bryan. By receiving a Confederate commission as a captain, he avoided execution and was exchanged in 1862. During his incarceration, Bryan was held in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, where he had been the victim of a system of informants established by the warden. Disguised as fellow prisoners, these informants would eavesdrop on the prisoners to gather intelligence. This experience likely helped Bryan develop a plan to approach Rushby. Using the guise of another captured Union officer, Bryan would deceive him into compromising the signal system.

Bryan was from Prince Georges County, Maryland, so his Southern accent was not particularly thick. In addition to being an educated, upper-class, former state legislator, Bryan also understood at least the rudiments of the Myers flag signaling system. He had been taught to use it to signal information across the Potomac River prior to his capture. With his neutral accent, intelligence experience, and a personal understanding of the mental state of a prisoner, Bryan was perfectly suited to make the false flag approach to Rushby.

The Sinking of the USS Keokuk

As the Confederate intelligence operation evolved, the Union Navy made its move against Charleston. After months of delays and under pressure for success from President Lincoln, Assistant Secretary Fox ordered the Union Navy to attempt to take Charleston with just ironclad ships. The resulting attack on April 7, 1863, was a debacle. After taking over 500 hits from Confederate batteries around Charleston harbor, the Union fleet limped back to sea.

That night, just off Confederate-held Morris Island south of the harbor entrance, one of the ironclads, USS Keokuk, sank. As required, her copy of the Code of Flotilla and Boat Squadron Signals was thrown into the sea to prevent capture. However, because she was so close to the beach, parts of the book washed ashore. Beach patrols retrieved the pieces the next morning and they were forwarded to the Confederate headquarters in Charleston. Bryan realized that the Keokuk signal book pages could play in a role in the deception of Lieutenant Rushby.

Bryan’s Masterful Deception

On April 8, 1863, dressed in a Union officer’s uniform with the pages of the recovered Keokuk signal book tucked into his boot, Bryan was placed into Rushby’s cell. Rushby, doubtless isolated and scared, was probably delighted with some companionship and the two appear to have quickly bonded. Bryan, with his basic knowledge of signaling, convinced Rushby that he too was a budding signal officer. To further the deception, Bryan produced the Keokuk signal book pages from his boot, claiming to have smuggled them past the Confederate guards.

Rushby was totally taken in. A Manhattan urbanite, alone and a prisoner of the South Carolina rebels, he was a prime candidate for the deception. Bryan suggested that, to make the time pass more pleasantly until they were exchanged, Rushby teach Bryan what he knew about signaling. In this way, Bryan was able to learn much about the Union system, including the cipher key, the Federal system of signals, and several letters of the Federal code.

To complete the deception, Bryan was removed from the cell that night, allegedly to be exchanged. By June, Rushby himself had been exchanged and was back in Manhattan on leave. There is no indication that he ever mentioned his fellow prisoner or how they had spent their time in Charleston.

Markoe’s Corps Holds the Key

Bryan reported what he had learned to 23-year-old Lieutenant Francis (Frank) H. Markoe, Jr., chief of the Confederate Signal Corps in Charleston. Markoe was a Washington, D.C., native and son of a former senior State Department bureaucrat ousted for his Southern sympathies. Markoe put several signalmen to work with Bryan’s information, and within hours the Confederates were reading the Union signals. On April 13, the Confederate commander in Charleston triumphantly declared in a telegraph message: “Have obtained key to signals of enemy. Can read many dispatches of the fleet, but am watchful of deception. Will send you key.”

Now able to make sense of the Union signals, the Confederate forces quickly expanded what would today be called a tactical signals intelligence unit within their own Signal Corps. Some 12 out of 76 Confederate signalers in Markoe’s corps were detailed to the unit. Operating in three-man teams, they intercepted Union signals from several vantage points on Sullivan’s Island to the north of the harbor mouth. With one man watching the Union signaler through a telescope and announcing his flag movements, the second wrote down each movement while the third man stood by to relieve either of his companions. With the ability to read the Union ship-to-shore communications, the Confederates could track the plans of Union forces.

Markoe’s success was almost his undoing, as knowledge of his men’s code breaking soon became widespread among Confederate officers. The problem was that the Confederates recorded intercepted Union signals in the same ledgers as the signals sent between their own units. Thus, every Confederate officer who passed through headquarters learned of the unique information available from the intercepted Union signals. In an effort to contain the damage, Markoe ordered his men to deny all knowledge of intercepts if asked.

Union Repelled at Fort Wagner

Despite the security concerns, the Confederates maintained their intelligence advantage and were forewarned of every Union attempt to storm Charleston’s defenses. The 1862 Savannah operation seemingly provided the Union with a blueprint for success. Seize a barrier island, position rifled artillery within 2,000 yards of the masonry fort guarding the harbor entrance, pound it to dust, occupy the fort, and seal the harbor. In what appears to have been an attempt to repeat their Savannah triumph, Union troops landed on Folly Island outside Charleston in April 1863 and advanced north across Lighthouse Inlet to Morris Island in July. With the guns of the fleet keeping the Confederates at bay, they attempted to move within effective artillery range of Fort Sumter.

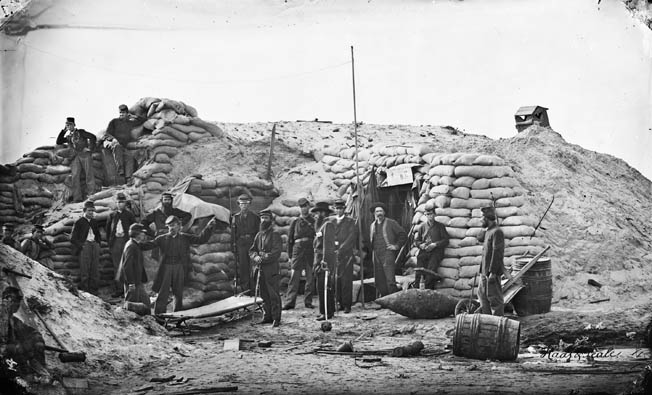

At Savannah, the Confederates had relied on the false security of the brick walls of Fort Pulaski to withstand the Union artillery. By merely evacuating the barrier islands, the Confederates allowed the Union to place rifled artillery within 2,000 yards of the brick fort. Having learned their lesson, the Confederates dug in and vowed to keep the Union artillery out of effective range of Fort Sumter. Fort Wagner, no more than a large pile of sand and logs, was strategically located at the narrowest part of the island 2,600 yards from Fort Sumter.

Before Union forces could hope to destroy Fort Sumter, they first had to eliminate Fort Wagner. Because the sand walls of Fort Wagner absorbed cannon fire like a sponge, Union forces were unable to destroy it with artillery and naval gunfire. Guessing it was lightly manned, Union leaders decided to storm the fort in a night assault, an unusual tactic for the time. In the late afternoon of July 18, 1863, the Confederate signal station on Sullivan’s Island, north of the harbor mouth, intercepted a message between Union forces on Morris Island and the Union naval gunfire support ships: “An assault is ordered at dusk. Husband your ammunition so as to deliver a rapid fire the last half hour.”

The intelligence was quickly disseminated and Confederate artillery in Fort Sumter and batteries on nearby islands all trained their guns on the stretch of beach that Union troops would cross to assault Fort Wagner. The warning gave the Confederates enough time to reinforce Fort Wagner. At dusk, as the Union units left their trenches, concentrated Confederate artillery fire hit them with devastating effect.

The Union attack on Fort Wagner failed with approximately 30 percent casualties; the soon-to-be-famous 54th Massachusetts suffered 47 percent casualties.

“Siege of Regular Approaches”

Union forces spent the next two months conducting a textbook “siege of regular approaches,” a system developed in France nearly 200 years before. The system basically consisted of moving to within striking distance of a fort using zigzagging trenches that reduced exposure to the fort’s weapons. By early September, the Union Army, with continuous naval gunfire support, was in position for the final assault on Fort Wagner.

To cut off Confederate retreat and position themselves to attack Fort Wagner from the rear, Union forces planned to take Battery Gregg on Cummings Point, the northernmost tip of Morris Island. As they had done in June, Union leaders proposed an unorthodox plan, a night amphibious assault up a creek to the rear of the fortification. The Army was to supply the assault force but the Navy was to supply boats and crews. At 1:30 on the afternoon of September 5, 1863, the Confederate signal station on Sullivan’s Island intercepted a Union Army message to the fleet offshore: “I am going to try Cumming’s Point to-night, and want the sailors again early.”

Again, the intelligence was disseminated quickly. As had happened in July, every Confederate artillery piece within range was aimed at the likely approach, the mouth of Vincent’s Creek, and the position again was reinforced. On schedule, the Union assault force rowed quietly down Vincent’s Creek past Fort Wagner toward the beach behind Battery Gregg. As they approached, the Confederates opened fire. The surprise attack was itself surprised and in the confusion, the boats raced back up the creek. Battery Gregg, the escape route for the garrison at Fort Wagner, remained in Confederate hands. The following night, the Confederates used it to evacuate all their troops from their doomed positions on Morris Island.

Defeat at Sumter

With the evacuation of Morris Island, Union leaders thought the Confederates were demoralized and a rapid assault could carry the key to the harbor’s defense, Fort Sumter. The Navy was quick to reach for the glory. On September 8, 1863, at approximately 2 pm, a signal officer aboard the Confederate ironclad ram CSS Chicora was observing the signals of the Union fleet’s flagship. Able to decipher the signals, the officer realized that the Union Navy was planning another unusual nighttime amphibious attack, this time targeted directly at Confederate-held Fort Sumter: “General Gillmore—I am going to assault Fort Sumter to-night. Admiral Dahlgren.” Again, the Confederates swiftly disseminated the intelligence and trained every gun within range onto the expected approach.

The Confederates held their fire until the first two waves of boats had landed the sailors and Marines on the rocky beach beneath the walls of the fort. Then, Chicora and guns from islands on both sides of the fort opened fire. The cannons raked the beach while musket fire and hand grenades poured down from the fort. Years later, a Union Navy officer captured on the beach that night wrote that the Confederates appeared to have been expecting the attack. As with the assault on Fort Wagner in July, the Navy and Marines suffered nearly 30 percent casualties, mostly personnel cut off on the beach and forced to surrender.

With the failure of the Navy assault on Fort Sumter, cooperation between the Union Army and Navy faltered. Satisfied that Sumter was effectively neutralized and with his troops exhausted, the Union Army commander ceased any major offensive operations. Without control of Fort Sumter, the Navy could not enter Charleston harbor. For the next two years Charleston remained in Confederate hands, while Union forces were confined to the barrier islands and the sea beyond.

Discovering the Intelligence Coup

In February 1864, a Union raid overran a Confederate signal station on Johns Island, just south of Charleston, and discovered a cache of intercepts. Alerted to the Confederate signals intelligence operation, Union signalers were soon able to work out the Confederate signal system and thus began a battle of ciphers and cryptanalysis that would last until the end of the war.

The Union signalers did not realize that the Confederates had already been reading their enciphered signals for nearly a year and that they continued to read all Union signals until they evacuated Charleston in 1865. When Union forces entered the city, they recovered one of the ledgers the Confederates used to record signals; it was only then that the Union Signal Corps fully realized the communications security disaster that had befallen their forces two years before.

Fates of the Men Involved

The war was over a few months later, but Edward Pliny Bryan, the Confederate spy, did not live to see it. After his intelligence coup in Charleston, he was promoted to major and detailed to command mining operations along the St. John’s River in Florida. He was recalled to Charleston for temporary duty in August 1864 but contracted yellow fever and died there in September at the age of 34.

Caleb Jones, the Spanish Wells guard, never saw Maine again. He remained a prisoner for several months but was eventually exchanged. While being processed for repatriation at a Union Army camp near Annapolis, Maryland, Jones contracted typhoid fever and died in September 1863. He was 46 years old and left behind a wife and four children.

Frank Markoe, the Confederate signals intelligence officer, ended the war as a staff officer in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. He settled in Baltimore where he prospered in the insurance business and returned to military service as an officer in the Maryland National Guard. He died in 1914 at the age of 74.

In 1864, John Mickler, the Confederate commando leader, was wounded fighting with the Army of Northern Virginia and furloughed home to South Carolina. He surrendered in Georgia at the war’s end. During Reconstruction, Mickler became a fugitive after organizing a vigilante group in South Carolina. He fled to Florida, finally settling in Saint John’s County where he died in 1885 at the age of 54.

After his leave in New York, Thomas Rushby, the Union signal officer, reported to Signal Corps Headquarters in Washington and was swept up in the final phase of the Gettysburg campaign. For 10 days, he manned a signal station near Harpers Ferry while the Army of the Potomac attempted to locate the retreating Confederate army. Rushby then reported to a new posting in the Department of Ohio eventually ending the war as a brevet captain in Raleigh, North Carolina. After the war, Rushby returned to New York City, married, and established a career as an executive with the J.L. Mott Iron Works. He died in Harlem in 1915 at the age of 79.

Confederate Victory Through Expert Intelligence

The Union forces attempting to seize Charleston were thwarted in large part due to an expertly managed Confederate intelligence operation. From Mickler’s commando operations that captured Jones, identified the signal station, and then snatched Rushby, to Bryan’s human intelligence operation that elicited the signals system’s secrets, to Markoe’s signals intelligence operation that broke the code and intercepted the signals, the Confederates did nearly everything right. A careful examination of the historical record demonstrates that all of these events were part of an orchestrated effort by the Confederates to read the Union’s Myer signal system used for ship-to-shore communications.

Some historical accounts attribute the breaking of the Union signal flag code to the recovery of the USS Keokuk signal book, but that is not accurate. The Keokuk book was a naval signal book, not the Myers system. It contained instructions for the use of the naval flag system, the system of multiple flags displayed from the yardarms of ships and used for ship-to-ship communications.

While the Confederate intelligence operation was imaginative and resourceful, helping to delay the Union occupation of Charleston for two years, it had little strategic impact on the war. By the time the Union campaign ground to a halt on Morris Island, the Union victory at Gettysburg had rejuvenated the Northern war effort. The Charleston campaign was relegated to the dustbin of history. Ironically, the most lasting impact of the Confederate intelligence operation at Charleston was to immortalize the lead Union unit devastated in the July 1863 assault on Fort Wagner. That regiment, the 54th Massachusetts, was the first African American unit to see combat in the war, and their heroic sacrifice, even in defeat, helped pave the way for thousands more to flock to the Union cause.

An excellent article. I had not read much about signaling and encryption during the civil war but of course they had the entire world’s history of encryption to draw upon

Who put this narrative together? Considering that many participants did not outlive the war or left memoirs. Did Rushby ever learn how he had been used by Confederate Intelligence?

How is it that the Union Signal Corp didn’t begin to suspect that their system had been compromised?

I’m amazed at how effective intel can be. It took the USA troops over a year to figure that they had been compromised by their own flag signals.

A great story. The contributions of the Confederate Signal Corps are well known, as are the efforts by both sides to read their opponents messages. Bryan’s story is documented in a few secondary sources but, I was very curious if the author had access to original sources. Unfortunately, the C.S. Signal Corps was also the office for covert activities. As such, much documentation was destroyed rather than risking it falling into yankee hands. Also, the postwar home of William Norris, the corps’ leader, was damaged by fire destroying additional documents that might have told some interesting stories. Any hope of seeing a list of references for the article?