By Michael D. Greaney

One of the most devastating events to shake the early Roman Empire was the defeat of Legate Publius Quinctilius Varus and his army at the hands of Arminius in the Battle of Teutoburgerwald in 9 ad. Arminius, or Armin (also known by the presumed Teutonic version of his name, Hermann), was of the Cherusci, the tribe most involved in the revolt. The battle was the worst setback to Roman territorial expansion up to that time. Unlike previous defeats, it was not the signal for regrouping, consolidating and carrying on the fight later. There was a fundamental shift in Roman foreign policy, with the Rhine established as the imperial frontier.

In his Historiæ Romanæ, Gaius Velleus Paterculus relates that the dreadful news of the defeat was received in Rome five days after the conclusion of the war carried out by Augustus in Pannonia and Dalmatia. The Pannonian war was the result of a master plan to develop a Roman province of Germania along lines laid out by Tiberius (Tiberius Claudius Nero, born BC 42, emperor 14 ad, died 37 ad), and his younger twin, Drusus. Nero Claudius Drusus died in BC 9, presumably in a fall from a horse or, as others recount, from a wasting disease while on campaign in Germania after appropriate portents. A festival in celebration of the end of the long and costly war was about to begin when word arrived that three entire legions, the XVII, XVIII and XIX, had been cut to pieces in Germania, along with three troops of equitati (cavalry), and six cohorts of auxiliaries. Approximately 20,000 men had perished.

Augustus, fearful of a general uprising among the many German and Gaulish inhabitants of Rome, both civilian and military, ordered the army to patrol the city at night. Since the Germans and Gauls were perceived as being the same people, Augustus sent all the unarmed representatives of both out of the city. He then transferred all German and Gaulish military personnel to distant islands where, in the event of a rebellion, they could cause little harm.

This was not the first defeat suffered by the Romans, nor the only one in Germania. The defeat of the Legate Marcus Lollius in BC 15, although as devastating, was considered “merely” ignominious, but that of Varus endangered Rome herself. Augustus gave additional orders to extend the term of all provincial governors throughout the Empire so as to have trustworthy men upon whom the allies and fœderati of Rome could depend. He also vowed to celebrate expiatory games in honor of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (“Jupiter the Best and Greatest”) as soon as the political situation improved.

It was the personal effect on Augustus, however, that seems to have made the greatest impression on chroniclers and contemporaries. Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus relates that, “Indeed, it is said that he [Augustus] took the disaster so completely to heart that he left his hair and beard untrimmed for months; he would often beat his head on a door shouting, ‘Quinctili Vare, legiones redde!’—‘Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions!’—and always kept the anniversary as a day of deep mourning.”

P. Quinctilius Varus: A Lazy and Corrupt Roman Commander

While 19th-century Romantics attempted to make a national hero of the German leader Arminius and credited the victory to the intrinsic superiority of the Aryan race, Roman historians put the blame squarely on the shoulders of the commander of the army in Germany, P. Quinctilius Varus. Certainly few of them have anything good to say of a man under whose leadership Rome suffered one of its worst disasters. Some recent historians have attempted to characterize Varus as an unfortunate scapegoat whose reputation was sacrificed to Roman pride, but the comments of contemporaries support a less worthy reading of the man.

Paterculus in particular points out the flaws in Varus’s character, although he retracts some of his statements later. He notes that while Varus came of noble lineage, it was not illustrious. He also claims that Varus was lazy in both mind and body, and preferred to take his ease in camp instead of campaigning in the field destroying Cæsar’s enemies like a proper Roman. Astonishingly for a civilization that viewed public office as a normal means of self-enrichment, Varus was considered exceptionally greedy and corrupt as an administrator.

An epigram related by Paterculus was that while governor of Syria from BC 6 to 4, Varus entered the rich province a poor man, and left the poor province a rich man. Flavius Josephus goes into great detail about Varus’s activities in Judea, at that time linked administratively with Syria, cataloging the seemingly endless list of uprisings that took place during his term of office. Even considering the fact that Josephus’s goal was to curry favor with the Romans, the Jewish historian hints darkly that Varus was responsible at least in part for the course of Herod the Great’s bloody career.

Varus had previously served as governor of Byzacene (c. BC 76), a country in North Africa on the coast south of Carthage. He had earlier attained the Consular dignity in BC 13, probably more on the strength of his marriage to a grandniece of Augustus than anything else. The objective record of his career seems to demonstrate a man with more influence than talent.

Varus’s Ill-Fated Attempts to Civilize Germania

Following his Near Eastern venture, Varus dropped out of sight for a while, presumably to enjoy his Syrian loot in the fleshpots of Rome. Probably needing to replenish his coffers, Varus finagled an appointment to an obscure post in the new province of Germania about 12 years later. Augustus might have felt his rapacious in-law could do little harm among the swamps, woods and complacent barbarians of the north while filling his purse. Among these “savages” were the Cherusci, at this time following a program laid out to civilize them over time without upsetting them or outraging their current customs and way of life.

The situation was delicate, although not dangerous until Varus showed up. The Romans had a portion of the area under control, but not all. It was winter quarters for a number of the legions, and the inhabitants were becoming gradually used to Roman ways and Roman rule. Cities were being built, markets established and Roman forms of government implemented.

The new legate, however, started off on the wrong foot. So great was his arrogance that he presumed the Germans were human in appearance only, and proceeded to enforce his idea of a civilizing program by stirring up the inhabitants with all manner of insulting and degrading imposts and regulations. Cassius Dio, the Greek historian of the reign of Augustus, relates that Varus treated the Germans like slaves, even levying tribute from them as if they were a conquered people instead of fœderati presumably enjoying the benefits of Roman imperium. Impatient with the progress being made, and anxious to establish his ascendancy and start collecting graft, he implemented his own accelerated program ill-suited to imposition on a proud people, with the expected results.

Although considered “savages,” the Germans of whatever tribe were also, according to popular opinion of the time, “exquisitely artful, a race, indeed, formed by nature for deceit,” and far from stupid. The leaders were anxious to regain their former condition of ascendancy, and the common people were chafing under the impositions of Varus. He was apparently operating under the assumption that he could treat Germans as he had Syrians. The Germans therefore decided to bide their time and await an opportunity for revenge. Given Varus’s incompetence both as civil administrator and military commander, this was not long in coming.

Arminius: A Roman-Trained Barbarian

The Germans were fortunate in locating Arminius, a war leader who had benefited from Roman military training. He was the son of a Cheruscus noble named Segimar. Arminius was notable for being “brave in action, quick in apprehension, and of activity of mind beyond the state of barbarism, showing in his eyes and countenance the ardor of his feelings.”

Arminius had served as a German fœderatus in the auxiliaries, and was thus a Roman citizen, it being the custom to grant citizenship upon completion of service. He had been raised to the Equites, the Equestrian Order (usually translated as “knights”) for his outstanding services to the Res Publica. Many of the men whom Arminius would be leading had also served in the Roman military, a fact apparently forgotten by Varus when he assumed that he could carry out a program of subjugation with impunity.

While Cassius Dio paints Arminius more as being the right man in the right place at the right time, Paterculus makes him the chief plotter, taking advantage of Varus’s incompetence to carry out atrocities, “not unwisely judging that no man is more easily cut off than he who feels no fear, and that security is very frequently the commencement of calamity.”

Warning of Arminius’s Plot

Arminius opened his mind to a few well-chosen confidants. Receiving encouragement, he sounded out a broader base of support. He assured the people that the Romans could easily be surprised and defeated in detail. In this he was helped not a little by Varus himself.

Arminius and his co-commander Segimerus constantly put themselves in Varus’s company, and were frequent guests of the officers’ mess. This gave them not only the opportunity to play on Varus’s weaknesses by flattering him at every opportunity, but also to size up their opponent on his home ground. Varus could not believe that two such genial fellows, barbarians though they might be, would plot against their good friend. Against Rome, possibly, but Varus himself? Never!

A Cheruscus fœderatus named Segestes, still apparently holding a hope that there could be a peaceful resolution to the situation, warned Varus during a feast immediately prior to the rising when he learned that a time had been selected to carry out the insurrection. Segestes went so far as to insist that Varus arrest Arminius and all the other leaders, including himself, which would immobilize the plot. The governor could then separate the innocent from the guilty at his leisure.

Segestes was forced to go along with the plot and fight alongside Arminius because the Cherusci were fully committed to the war. In addition to his political misgivings, however, Segestes had a personal grudge against Arminius. His daughter, engaged to another man, had been abducted by Arminius, causing lasting enmity between the two men. Knowledge of this quarrel may have led Varus to believe that Segestes was simply attempting to blacken the name of Arminius, that good friend of Varus and all Romans, and that there was no foundation to the story other than envy.

For whatever reason, Varus refused to believe Segestes. The Roman governor professed to trust in the good will of the people and their love for him, which they had expressed on numerous occasions in order to lull him into a false sense of security. It was a fatal exercise of fatuous self-deception.

The Battle of Teutoburgerwald: Fact and Fiction

At Arminius’s suggestion, Varus then made a mistake deadly to any commander in hostile territory. He dispersed his forces among people whom, he was assured, desired protection against possible incursion by (other) barbarians. Almost immediately after this misjudged action, a contrived rebellion broke out among those who lived farthest from the Roman base. This was in order to ensure that Varus would have his troops strung out on a long and arduous march through mountainous and wooded, though presumably friendly territory, burdened with baggage and camp followers.

Unlike most such plans, the arrangement worked to perfection. Locals rose and slaughtered detachments quartered on them ostensibly for their own protection. This not only dealt a severe blow immediately, but also prevented Varus from receiving critically needed reinforcements, the deployment having used up his reserves. The Roman commander set out through the Teutoburgerwald (the Teutoburg Forest) to crush the rebellion. Presumably under the illusion that he was in for a short, glorious little war, Varus burdened the columns with baggage wagons, and even soldiers’ families and vast numbers of servants, “as they would for a journey in peace-time,” thus ensuring that the advance would be broken up into small groups. He apparently still fancied that Arminius and Segimerus were his faithful allies.

Specific details of the battle are impossible to reconstruct from the remaining evidence. Paterculus promised to relate the exact circumstances in his “large history” but, if he carried out his promise, the work has been lost. The details given by Cassius Dio contradict in some respects the evidence found by the expedition of Germanicus and recorded by Cornelius Tacitus in the Annales. Even Tacitus cannot be considered completely reliable, for archeological findings have yet to verify the events he described.

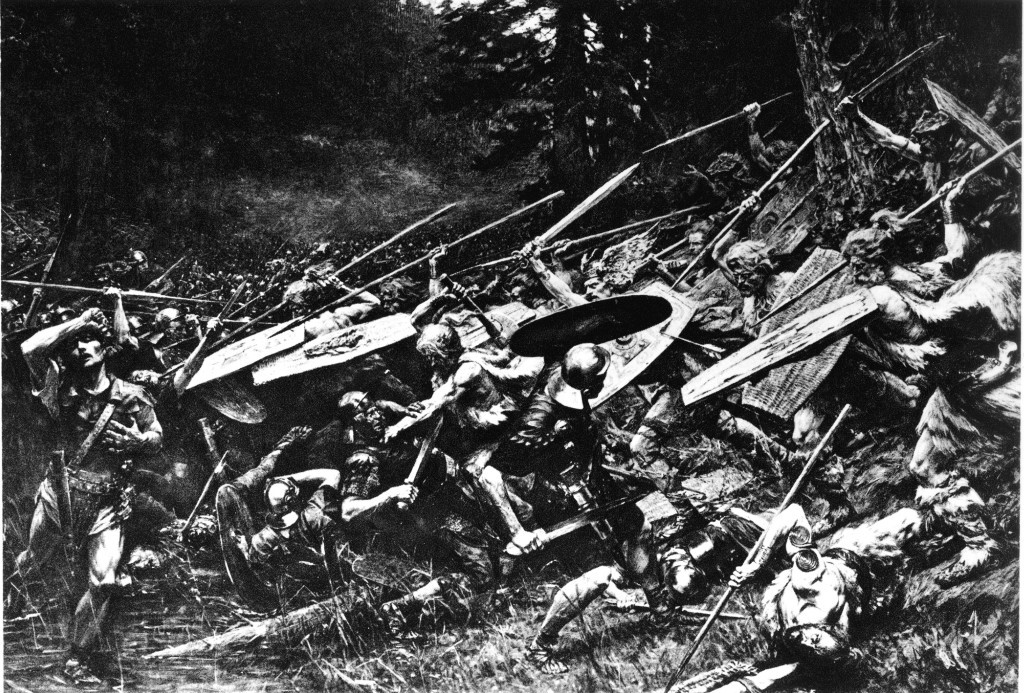

The battle began badly for the Romans, and ended worse. One excessively romantic source, intent upon turning Arminius into a Teutonic superhero, relates the disingenuous story that, in order to fool the Romans into thinking that they were outnumbered by a small barbarian force, the Germans made great shouts and beat their shields with their swords.

A few errors were committed in this exercise in myth formation. First, the Germans were not “vastly outnumbered” as the source claims, but probably had a slight superiority in numbers thanks to the success of Arminius’s stratagem that resulted in Varus splitting his forces for easier slaughter while on garrison duty.

Second, the majority of the Germans were not armed with swords at this time, but with short spears called frameæ. Swords were expensive and difficult to manufacture. They were not common among the German tribes until centuries later. Finally, Arminius was a trained Roman officer, and hardly likely to think that, foolish as their commander might be, the Roman soldiers would be hoodwinked by such a childish trick. He had arranged the confrontation in a far more effective manner.

The Battle According to Cassius Dio

In his battle plan, Arminius was aided not a little by a terrible storm that broke out—which incidentally would have drowned out any shouting or other noise-making intended as a diversion. The storm caused the already-fragmented columns to break up even more. It was then that Arminius made the first attack.

Initially the Germans threw their spears from a distance, screened by the underbrush and the confusion caused by the storm. Encountering no effective resistance, they closed in. The Romans, scattered among the baggage train and mixed in with noncombatants, were unable to form up and concentrate their forces properly. This increased the number of casualties dramatically and prevented any attempt at a counterattack.

Somehow the Romans managed to fight their way to “a suitable place,” as Cassius Dio describes it, where they made camp, fortified with a trench and a stockade. In this operation, they would probably have been protected by cavalry screens presumably under the direct command of the Legate Numonius Vala. Vala seemed to work well with the auxiliaries and employed both the Roman equitati and the allied horse to good effect.

It is at this point that the account given by Cassius Dio begins to contradict the evidence found by Germanicus six years later and recorded by Cornelius Tacitus in his Annales. Germanicus (Germanicus Tiberius Cæsar) was the son of Nero Claudius Drusus, the younger brother of Tiberius Cæsar. Nero Claudius Drusus received the title of “Germanicus” at his death for his attempts to extend the Empire northward, and it was conferred on all his male descendants. It is a coincidence that Germanicus Tiberius Cæsar’s military feats were in Germania.

Cassius Dio relates that the next day, having burned or abandoned most of the baggage train, the column marched out in good order. How the wagons could have been burned after the torrential downpour the historian had already described is not explained. According to Cassius Dio, the Romans even made it to open ground, suffering minor casualties. Then, for no discernible reason, they re-entered the woods, where they suffered the heaviest casualties of the battle.

Unable to form up properly for a charge, the Romans were decimated over the next two days until, on the fourth day, another heavy rainstorm made even maintaining footing impossible. Cassius Dio neglects to relate anything that happened on the third day, leaving many modern readers to suppose that the “fourth” day was a misstatement, it actually being the third. In any event, the soldiers were unable to employ their missile weapons because of the trees and the downpour. Even their shields were too heavy to hold, having become sodden with the continued rain. Those officers not already slain committed suicide. They were followed by those of their men who did not simply cast down their weapons and wait for death.

A Battlefield 50 Kilometers Long

The evidence found by Germanicus’s expedition suggests that the battle did not go quite as Cassius Dio reported, especially on the second day. The nephew and heir of Tiberius Caesar found the fortified camp constructed on the first day of battle. There was, however, more than a suggestion that the stockade had been assaulted and breached, probably early on the second day. There was, of course, no effective way of carrying out a fight at night under conditions in a dark forest with an overcast sky.

Once the stockade was breached, the Roman soldiers probably made a run for it. Far from putting up an effective defense, Paterculus asserts that Varus punished men for attempting to fight their way clear. Sensing that all was lost, Numonius Vala failed to provide cover for a retreat. Although normally he “conducted himself as a modest and well-meaning man, [he] was on this occasion guilty of abominable treachery.” Vala deserted with the auxiliary cavalry and tried to reach the Rhine on his own. His “Fortuna” deserted him in turn, however, and he perished in the attempt, along with most of the auxiliary troops.

The heaps of whitened human and animal bones found by Germanicus indicated that some groups of soldiers had attempted to stand and fight, while others had been slain while running away. The Romans had been unable to reform and present a united front. The woods and rain rendered them unable to use their bows and javelins to any good effect. What may have started as an attempt at an orderly retreat after the breaching of the stockade became a three-day Great Hunt with man as the game. The running battle covered a killing ground estimated at over 50 kilometers.

The Germans were at a substantial advantage, not being troubled with heavy armor in the mire. While they lacked swords and used spears, these, like the Zulu assagai, were more often used for thrusting than throwing. This made them good close-order weapons, ideal for the conditions under which they were fighting. The Germans also had the advantage of receiving constant reinforcements, while the Romans had already suffered heavy losses the first day.

Reports as to the end of the battle differ. Most sources hold that Varus and all the senior officers, “fearing that they would either be taken alive or slaughtered by their bitterest enemies—for they had already been wounded—nerved themselves for the dreaded but unavoidable act, and took their own lives.”

Of the two camp præfects, Paterculus reports that Lucius Eggius took the path of honor and committed suicide, while Ceionius preferred life and disgrace to honor, and advised surrender, probably living just long enough to regret his decision. The centurions and senior officers who survived were sacrificed on altars especially constructed for the occasion near the first day’s camp. Their heads were cut off and nailed to trees in the area, to be found years later and removed for decent burial. Germanicus himself laid the first sod for a memorial mound in a triangular cemetery near the stockade, an act for which Tiberius rebuked him. The Emperor apparently construed it as an exercise of imperial authority to make a public demonstration of honor for the dead. The memorial mound was later destroyed and never rebuilt, making the search for the site significantly more difficult than it would have been.

Where Was the Battle of Teutoburgerwald Fought?

The specific location of the main battle is still a matter of conjecture. The clues in the various accounts are of little use after almost two millennia. Over seven hundred possible sites have been investigated with little result. The most promising area is in the neighborhood of Oberesch, today occupied by a farm. In 1987, Major Anthony Clunn of the RAF, stationed with a helicopter squadron in Osnabrück, reported seeing a site in this location during a “flyby” (authorized, one hopes) that could be the battlefield.

Archeological investigation began almost immediately, but it was not until 1994 that the first traces were found of human and animal remains, as well as military equipment. Additional traces have been found since, but nothing to indicate the location of the fortified camp, the wreckage of which was found by the expedition led by Germanicus six years after the battle, or of the triangular-shaped cemetery in which the remains of those Romans whose bodies could be located after more than half a decade were interred.

The area in which most of the remains have been found is in the narrowest gap in the mountains between Wiehengebirge and the Great Moor, known today as the Niewedder Senke. This is a clear indication that what had been found was probably the location of the desperate fighting during the attempted retreat on the second day of battle. The remains of the fortified camp and cemetery could thus still be many kilometers away. There is one thing upon which all authorities agree, however: The site of the “Hermannsdenkmal,” the monument to Arminius begun in the 1840s and completed in the 1870s, is not the location of the battle.

The Lasting Effects of the Roman Defeat at Teutoburgerwald

While devastating, the defeat in the Teutoburgerwald did not have exactly the effect that succeeding generations of German Romantics imputed to the disaster. Germanicus Caesar was sent north to quell the rebellion and defeated Arminius. Although successful, and one of the more popular and well-loved members of the imperial family, Germanicus met an untimely death in Antioch in 19 ad, presumably by poison. This was blamed by contemporaries on Tiberius out of jealousy for his adopted son and heir, but may have been the more usual instance of accidental food poisoning, commonly attributed to design in earlier times.

Arminius himself, although he regained the territory after the recall of Germanicus and rose to the position of chieftain of the Cherusci, became involved in the constant intertribal warfare that was one of the ostensible reasons for the imperial program of conquer, occupy and civilize. He was killed a few years later by his own relatives. The Germans mutilated the body of Varus, but cut off the head and sent it to Augustus who, after a while, gave it burial in Varus’s family vault.

Teutonophiles point with pride to the fact that Rome never again succeeded in making any great additional territorial expansion in Germany. This is generally attributed to the virility and strength of the pure Aryan strain opposed to the decadent and degenerate Romans and those weak enough to succumb to civilization.

True, the Cherusci were the most intractable of tribesmen, but there were additional reasons why Rome halted its program of expansion in that direction. A glance into Tacitus’s Germania reveals that, as far as the Romans were concerned, the country east of the Rhine was a vast wasteland containing little but savages, swamps and dark woods—hardly attractive to a Mediterranean people. The prospective province laid out by Tiberius and Drusus held within it some of the most difficult terrain in western Europe, and potential revenue for the Imperial treasury was small.

There were no known deposits of gold or silver and, unlike the more favored Gaul, no vast tracts of agricultural land. Farming equipment of the time was ill-suited for the sticky soil of northern Europe. An adequate plow would not be invented for centuries—after the Germans themselves began to adopt more settled ways, and needed effective tools to increase crop production. Tiberius’s realistic appraisal (the decision was his, Augustus having turned into a god in 14 ad) was to punish the Germans for the defeat inflicted on Varus, regain the eagles that had been lost—and abandon the place to the savages. The numbers XVII, XVIII and XIX were never again used to designate any legion.

Future policy was dictated by the desire to shorten the salient between the Rhine and the Danube in order to secure the borders of the Empire. This required establishing the longest artificial border in Europe, the Limes. It was characterized by small outposts on the frontier staffed with border troops, Limitanei, and larger military installations behind the lines, with garrison troops, Comitatenses, near the cities on the interior lines of communication ready to move in whatever direction danger threatened. It was not until the reign of Marcus Aurelius (born 111 ad, emperor 161 ad, died 180 ad) that Rome was to have a larger vision concerning Germany, by which time she lacked the ability to sustain a campaign that could take generations.

The Empire dropped the practice of absorption through conquest and occupation, and adopted a policy of “build it and they will come.” The strategy was now to welcome barbarian settlers into the Empire on a limited basis, which in later centuries was to become a flood of immigrants. These would provide critically needed manpower for the legions, gain Roman citizenship and, after their term of service was up, a grant of land in a colony on which to settle their families and relatives as Roman fœderati. In the end, although the intent was to Romanize the Germans, what resulted in many respects was a Germanization of the Romans.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments