By Christopher Miskimon

The year 1942 was one of crisis for the Allied cause in the Pacific. Until May, almost everything had gone in favor of Imperial Japan. In that month the Japanese were stalemated at the Battle of the Coral Sea. If the Japanese Navy had succeeded in capturing Port Moresby at the southeastern tip of the island of New Guinea, Australia would have been in dire straits. In this desperate time, the threat was still serious as the Imperial fleet could return at any time.

This was a threat the Australians felt more than any. The nation was large, resource rich, and relatively wealthy while simultaneously underpopulated, poorly armed, and isolated. Australia lacked the population required to support an army capable of resisting Japan. Much of its military was spread elsewhere with a portion lost in Singapore, and many of its troops were fighting the Germans and Italians in North Africa. Vast distances separated the island nation from its most vital allies, the United Kingdom and the United States. For the citizens of Australia it seemed as if a Japanese fleet would appear over the horizon any day.

Nevertheless, the country did what it could to prepare. Some 130,000 troops remained, though most were untrained. As far as possible, likely landing beaches were fortified with barbed wire, trenches, and antiaircraft positions. A nighttime blackout was ordered for all lights within six kilometers of the coast, though curiously lighthouses were allowed exception from the order. Much as in Britain, Australians prepared to move their children to the countryside away from likely bombing sites. With England stretched to the limit, Australia began to turn to America for the support it needed, at the time a controversial move to many Australians. It would take time for the Americans to move significant strength to bolster Australia’s defense, however.

In the meantime, Japan continued to threaten. Imperial forces moved into the South Pacific, slowly closing a noose around the island nation. The Japanese knew that Australia would serve as a staging ground for the eventual Allied riposte and had to be neutralized. Australia was far too large a nation for Japan to physically invade and occupy; the Imperial Army was already stretched thinly, from northern China to remote outposts dotting the Pacific. However, the Japanese could seize a few more islands, such as Samoa, Fiji, and New Caledonia, among others. Using these islands as bases they could interdict the lines of communication between America and Australia, preventing the buildup necessary for a counteroffensive.

The setback at Coral Sea and the colossal defeat at Midway in June 1942 put a damper on that scheme, but Japan did not give up easily. An effective submarine campaign might well isolate Australia. Japanese naval doctrine called for using submarines as an adjunct to their surface battle line. Squadrons of subs would range ahead of the main fleet, hitting enemy forces and reducing their strength until the main Japanese armada could secure a decisive victory. Commerce raiding was a secondary mission but ultimately necessary. Given the requirements for surface ships elsewhere, submarines were the most readily available.

Midget submarines had been used at Pearl Harbor, but their mission was essentially a failure. Of the five tiny submersibles sent to wreak havoc along with the Japanese air attack, none achieved success and one almost ruined the element of surprise for the attack when it was spotted by the coastal minesweeper USS Condor and sunk by the destroyer USS Ward in the early morning hours of December 7, 1941. Still, the idea of using them for long-distance raids against enemy ports persisted, and the Japanese Combined Fleet’s commander, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, approved their deployment for two more attacks. One strike would be made in the Indian Ocean against British ships, while the second would be directed south to Australia.

The Imperial Japanese Navy’s 8th Submarine Squadron had responsibility for the midget submarines and the mother subs that carried them. Designated a Special Attack Group, the 8th was divided into two flotillas, East and West, with the Eastern Flotilla sent toward Australia. This force included six large submarines. Four of them, I-22, I-24, I-27, and I-28, were mother submarines that carried the midget subs into range of their targets. The other two, I-21 and I-29, carried floatplanes to perform reconnaissance. The squadrons each had a pair of submarine tenders, seaplane tenders, and armed merchant cruisers to support the subs.

On April 16, 1942, the East Flotilla left the port of Hashirajima on Japan’s Inland Sea. The group sailed to the naval base at Truk Atoll and prepared for the voyage to the target, Sydney, Australia. The Japanese plan was to launch their 46-ton midgets off the coast, close enough for them to sneak into the harbor and strike Allied naval vessels or merchant ships moored there. The crews were confident they could get into the harbor and carry out their attack, though they were less sure they could get back afterward.

The midget subs were attached to their mother vessels and had a hatch allowing the two-man crew to enter directly from the host submarine without surfacing. Each midget was just under 80 feet long and carried a pair of 18-inch torpedoes. With their electric motors they had a range of 150 nautical miles at five knots. The lead-acid batteries powering the motor could not be recharged after disconnecting from the mother. In case the crew was unable to rendezvous with the mother vessel, each midget had a scuttling charge to prevent capture. For this mission each sub had a junior officer in command with a petty officer as a navigator, responsible for steering. The commander could stand behind the navigator, manning a periscope.

Around May 18, the submarines left Truk and set course almost due south for the east coast of Australia. About a week later, I-29 launched its floatplane, a Yokosuka E14Y, Allied code name Glen, on a reconnaissance flight over Sydney. Arriving over the city just before dawn, the pilot and navigator surveyed the harbor and saw a large number of Allied warships moored around its various quays and docks. Their mission a success, they turned back to the I-29. Upon landing, however the Glen was damaged beyond immediate repair, unusable for the rest of the mission. At 1:30 the next morning, the Eastern Flotilla was ordered to make its attack on Sydney.

By May 29, five submarines had gathered some 35 miles off Sydney. As they prepared for their task, Vice Admiral Teruhisa Komatsu, commander of Submarine Squadron 1, sent a message from his flagship at Kwajelein: “In seizing this once-in-a-thousand chance, approach the enemy with the utmost confidence and calm.”

In the Indian Ocean, the Western Flotilla was carrying out its own attack against the British anchorage of Diego Suarez. This port in Madagascar had only been in British hands a few weeks after a stiff battle to capture it from Vichy France. This attack succeeded in damaging the battleship Ramillies, taking her out of service for a year. A tanker, the British Loyalty, was sunk. Unknown to the Japanese sailors off the Australian coast, the mission at Madagascar had met with some bad luck as well. Only one of the two midget subs sent against Diego Suarez had made it into the harbor.

On May 30, the Eastern Flotilla’s remaining floatplane was launched on a second reconnaissance of Sydney Harbor. The pilot, Flying Warrant Officer Susumu Ito, took off from I-22 and successfully overflew the harbor area, confirming the presence of enemy warships, including one battleship (the “battleship” was actually the American heavy cruiser Chicago). The next day the mother submarines moved closer to the harbor mouth, taking position six to eight miles from it. Within their submerged hulls, the midget crews began preparations.

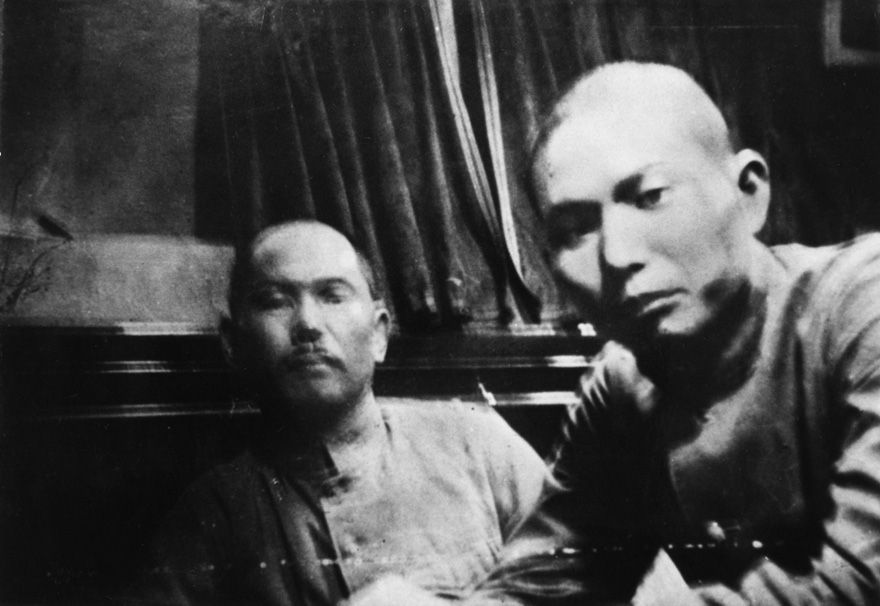

Aboard I-22, Lieutenant Matsuo Keiu and his navigator, Petty Officer First Class Tsuzuku Masao, not only prepared their submarine and equipment but their souls as well. Alongside the crew of the mother sub, they worshipped at a small Shinto shrine complete with candles. In a small ceremony, they honored the nine sailors who had died making the midget submarine attack on Pearl Harbor six months earlier. These men were known popularly as the “Nine War Gods of Pearl Harbor.” A photograph of them was shown around. Next a citation from Admiral Yamamoto was read, and the group sat down to a meal together.

During the repast Matsuo asked I-22 assistant torpedo officer, 2nd Lt. Muneaki Fujisawa, to cut his hair. The young officer agreed and shaved Matsuo’s head closely. Fujikawa recalled that his young comrade seemed resigned to death on his mission. During the haircut Matsuo said aloud, “I wonder what my mother is thinking at this moment?” Tsuzuku wrote a letter to his brother telling his sibling he had been killed near Australia on May 31. Both seemed to accept their task and the probable doom that came with it. A purification ritual followed, and then a change into fresh, perfumed uniforms. Matsuo also donned a thousand-stitch belt, a sash designed to protect the wearer from harm. Finally, a tea ceremony was held, its purpose to instill a feeling of tranquility before the coming action.

Similar events were happening on the other two mother subs. On I-27 Lieutenant Chuma Kenshi and navigator Petty Officer Omori Takeshi and on I-24 Lieutenant Ban Katsuhisa and Petty Officer Ashibe Mamoru prepared their craft. At about 5 pm, all three crews boarded their midget subs. Charts and lists of call signs were brought aboard along with food and drink. Matsuo also brought a sword his father had given him before he left. It was wrapped in a red bag made from the sash of his mother’s wedding dress. Once ready, the telephone line connecting the two vessels was severed and the clamps connecting mother to midget released. Now the midgets sat loose in their carry racks. A small amount of compressed air was injected into the ballast tanks, and the tiny submarines floated slowly and gently from their racks, rising steadily upward. Once clear, they could start the electric engines and begin the long, slow journey to Sydney harbor.

At 5:25 pm Lieutenant Matsuo’s submarine got underway. Three minutes later Chuma began moving, and Lt. Ban started at 5:40. The plan was for Chuma to enter the harbor first at 6:33, followed by Matsuo and Ban at intervals of 20 minutes. All three submarines were slowed by a strong southerly current and some unexpectedly heavy seas. By the time Chuma reached the harbor mouth, he was an hour behind schedule. Ban was two hours behind.

The Japanese aerial reconnaissance was noticed by the Australians, but curiously little was done about it. It was a dark, overcast night in Sydney, and heavy clouds hid the full moon overhead. The skies would not clear until after midnight. Despite the blackout, lights were on here and there where work crews were busy making repairs or improvements. Normal traffic continued. Ships were coming and going from the harbor, and the various ferry boats were darting about the docks delivering passengers. The Royal Navy officer in command, Rear Admiral Gerald Muirhead-Gould, was apparently aware the Japanese seemed to be up to something but chose not to call an alert.

At the harbor mouth, electronic indicator equipment was in place that could detect incoming or outgoing vessels; a trained operator could even tell whether the signature was of a submerged or surface vessel. If anything were detected, the sailor on duty could telephone the operations room on nearby Garden Island so the alarm could be sounded. A steel mesh torpedo net was also in place and watched by sentries. Small patrol boats were assigned to watch for intruders. Many of them were converted from civilian motor launches and equipped with machine guns and depth charge throwers. Shore batteries and antiaircraft guns were emplaced. In the harbor were over a half dozen Commonwealth warships, the American heavy cruiser Chicago, and some barges converted to floating barracks, along with the usual assortment of civilian ships.

Outside the harbor, Chuma lurked, searching for a way in. A ferry was steaming into the harbor, heading for the torpedo net, and the Japanese officer decided to follow in its wake. Slowly, at no more than six knots, the midget submarine trailed the ferry. Passing through the detection net, it left a discernable signature, but at the time it was not recognized as a submersible. As the ferry approached the boom and net, the midget fell behind, and Chuma decided to make for a second gap in the net. Veering off course, the tiny sub ran into the net and became stuck at 8:05. For 10 minutes the crew struggled to free the vessel to no avail.

Nearby a night watchman employed by the Maritime Services Board went about his duties, looking after some barges and pile drivers near the torpedo net’s boom. James Cargill, an experienced Scottish merchant mariner, had stopped to speak to another employee when he saw something in the water at 8:15. At first he thought it was a small launch running without its lights on. He knew it should not be there, so he set out in a rowboat to investigate. Arriving alongside, he saw what looked like a pair of huge oxy-acetylene bottles with a steel frame over them, probably the midget’s two torpedoes with their protective covers. He recalled, “I was convinced the mysterious object was either a mine or a submarine.”

There were two patrol boats on duty near the nets, and Cargill immediately rowed away to find one. At 8:45 he contacted the HMAS Yarroma, commanded by 21-year-old Sub-Lieutenant H.C. Eyers, a shipping clerk before the war. The young naval officer did not believe what Cargill saw was an enemy submarine but turned his boat’s searchlight on the area. They spotted the midget about 250 meters away, but Eyers announced it looked like nothing more than some wreckage.

Cargill argued, “It’s not. It’s moving backwards and forwards. You’d better hurry up or we’ll have no bloody navy left.”

The Scotsman even offered his rowboat to Eyers for a closer look. The Navy man not only refused the offer but would not move his patrol boat closer for fear it might be a magnetic mine.

In addition to his unwillingness to take action or investigate, Eyers did not even report what he had seen until over an hour later. All he sent was a description of a “suspicious object in net.” Headquarters took the matter more seriously and ordered him to investigate. Eyers still did not move his boat closer but did send one of his sailors with Cargill in his rowboat to have a closer look. The pair rowed alongside the midget sub, and Cargill used his flashlight to look it over. They could see the conning tower and periscope and the outline of the hull, part of which was about six feet out of the water.

Cargill said, “We could see … it was a submarine which had almost surfaced…. There was a light in the periscope…. By the time we got there the submarine had stopped struggling to get out of the net.”

While they were inspecting the sub Eyers, back on his patrol boat, made another report stating the object was “metal with a serrated edge on top, moving with the swell.”

Cargill and the sailor quickly rowed back to the Yarroma and told Eyers what they had seen. Another patrol boat, the 18-ton HMAS Lolita arrived, and Eyers ordered its commander, Warrant Officer Herbert Anderson, to move in for a closer inspection. Anderson was an experienced sailor but had not been in the Navy for long. Nevertheless, he took his boat in, stopping a mere six meters from the midget. Looking it over with his spotlight, it was obvious to him the object was a submarine. The front end stuck out of the water with the stern still under the surface. The periscope was plainly visible, and it was rotating as though the submarine’s occupant were looking around. Lolita’s spotlight beam reflected in the periscope’s lens.

Unlike Eyers, Anderson took immediate action. While he could have backed away and machine-gunned the sub, instead he turned stern-first to it and dropped three depth charges set to explode at 50 feet. None of them exploded; the water was too shallow. As Anderson pondered his next move, the Japanese crewmen must have decided the game was up. They detonated their scuttling charge, the explosion ripping a huge hole in the forward section and sending debris flying through the air. Both crewmen were killed instantly.

The Lolita was lifted by the bright orange blast, and chunks of the midget’s quarter-inch steel hull tore through the air over it. Cargill felt the Japanese had tried to take the Australian patrol boat with them. The sound of the detonation carried across the harbor; citizens came out of their homes to see what had happened.

As the drama of Chuma’s midget was unfolding, Lieutenant Ban’s submarine passed the detection threshold at 9:48. No one noticed. Ban followed a ferry through the nets. Slowly, his midget made its way into the harbor. By now Admiral Muirhead-Gould was aware something was going on and ordered a general alarm, instructing all ships to enact precautions against submarine attack. The port was also closed to outbound ships. The alarm order went out twice, at 10:27 and again at 10:36, about the time Chuma scuttled his sub. The admiral had been at dinner with Captain H.D. Bode of the Chicago and a few of his officers.

As Ban’s midget moved deeper into the harbor, it began to have problems staying submerged and kept popping up to the surface. Aboard the Chicago, Electrician’s Mate Art “Hank” King was the lookout on the 36-inch searchlight platform. His shift had been boring, and Hank had kept himself entertained thinking about an upcoming three-day shore leave. After a while, the duty electrician, “Moose” Clendenen, joined Hank on the platform. King remembered being amused by Moose, who had apparently never been that high on Chicago’s superstructure before. The man was taken by the spectacular view and kept talking about everything he saw.

Suddenly, Moose called out that he saw a submarine! Hank thought Moose had only seen a buoy a few hundred yards off Chicago’s stern and told him so. Moose replied that he saw the buoy and the submarine was farther to starboard and more distant than the buoy. Hank looked where Moose was directing him and, “Sure enough, I saw something resembling a small conning tower or large periscope coming up the channel at a slow rate of speed and leaving a tiny wake. Actually, its wake is what gave it away. The above water structure appeared to be black and barely discernible.”

Hank immediately reported the sighting to the officer of the deck and turned on the spotlight. The deck officer authorized Hank to open the light’s shutters, and in seconds the midget was illuminated. Momentarily, it disappeared below the surface and then reappeared closer to the ship, running parallel to it. One of Chicago’s 5-inch guns was manned, and the crew opened fire. The sub was too close, and the gun could not depress low enough to score a hit. One of the ship’s quad 1.1-inch antiaircraft guns tried hitting the midget, but these shots went over it as well.

For a short time the submarine disappeared, only to break the surface again slightly ahead of the cruiser’s bow. Hank turned the spotlight on it, and the gun crews poured fire into the submarine. The red tracers from the quad skipped across the water as the large 5-inch shells burst in geysers. From what the crews could tell, no hits were scored, and the midget again slipped under the water. Searchlights played across the bay trying to locate the sub. Red flares lit the smoky air.

As the Allied sailors searched, the midget changed course toward the Harbour Bridge. Ban’s sub was about 200 meters north of Garden Island when a small motor launch, the Nestor, spotted it directly ahead and had to swerve to avoid colliding with it. Afterward, sailors aboard two corvettes docked nearby, HMAS Geelong and Whylla, spotted the sub 200 meters away. Geelong’s captain ordered his crew to open fire with a 20mm cannon, but they had to wait until a passing ferry cleared the zone of fire. Once the ferry was out of the way the 20mm started banging away, sending over 100 rounds at the midget. It was not enough, and Ban was able to get his sub submerged again. He set course for a position to fire his torpedoes at Chicago.

As Ban was setting his attack, Matsuo, also running far behind schedule, had finally reached the harbor. At about 10:52 an unarmed patrol boat, the Lauriana, spotted the sub’s wake as it popped to the surface. Turning on their spotlight, the crew sighted its conning tower only 25 meters away. Unable to attack, Lauriana lost sight of the midget. Another patrol boat, HMAS Yandra, fortunately armed, moved over and spotted Matsuo’s craft. It rammed the sub but apparently struck only a glancing blow. The crew did get a good look at the sub but then lost it for a few minutes.

At 11:03, Yandra’s crew once again picked up the sub, this time some 600 meters away. The ship raced over, and six depth charges were heaved into the water. Each exploded at the preset depth of 30 meters, sending great plumes of foamy water into the air and shattering windows ashore. The midget was not spotted after that so Yandra’s crew thought their attack had sunk it.

Despite the fighting going on across the harbor, the ferry boats were still running around the bay. Admiral Muirhead-Gould had specifically told them to keep active, reasoning that more ships moving through the bay would help keep the attackers suppressed until daylight, shifting the advantage to the defenders. At 11:14 a further order was issued for all ships to turn off their lights. The lights on the docks stayed on until ordered shut off some 71 minutes later, at 12:25 am.

Four minutes after the dockyard lights went out, Ban was ready to attack Chicago. His midget was at a right angle to the cruiser, leaving its long flank wide open for a shot. The distance was only about 800 meters, and the moonlight kept the warship visible even after the lights were turned off. The ship looked like it was starting to move; smoke poured from its two stacks. Ban aimed slightly ahead of Chicago to compensate and fired.

The first torpedo lurched from its housing, dipped slightly to a depth of six meters until its propulsion system spun up, then it stabilized at 2.4 meters at a speed of 45 knots. It should take about 40 seconds for the torpedo to impact its target. After the underwater missile left, the submarine became much lighter at the bow and surged to the surface, causing Ban to lose track of his weapon. It took several minutes to get the midget underwater again.

Meanwhile, Ban’s aim had apparently been fooled by Chicago’s supposed movement. The torpedo soared ahead of the cruiser’s bow and continued toward Garden Island. Along the way it sailed under the K9, a Dutch submarine, before going on to pass beneath a depot ship, the Kuttabul. A former ferry, Kuttabul was docked alongside Garden Island and served as a barracks for a number of Australian sailors.

After passing under the floating barracks, the torpedo struck the retaining wall stretching along the shoreline of Garden Island. The explosion thrust Kuttabul out of the water in a torrent of spray, killing 21 sailors sleeping below decks. The blast also did severe damage to K9. Chunks of timber from the depot ship flew in all directions; half the ship’s wheel was consumed in the explosion. The concussion knocked out power and telephone service across the entire island. Kuttabul quickly began to settle by the stern.

Aboard the midget, Ban and Ashibe brought their craft under control again and launched their remaining torpedo. The deadly projectile raced through the dark water, missing Chicago by only four meters before continuing across the bay to the eastern side of Garden Island. There, it ran aground on some rocks and stopped without detonating.

As Chicago steamed out of the harbor, lookouts spotted a periscope alongside the ship at 2:56. The crew signaled the harbor defenses, and at 3:10 a pair of patrol boats, HMAS Steady Hour and Sea Mist were ordered to the area. The periscope had been spotted outside the torpedo net. The commanders of the two converted pleasure craft, Lieutenant Athol Townley and Lieutenant Reginald Andrew, respectively, cast off and got moving.

Townley was in overall command of the two boats as Andrew had just taken command of Sea Mist 11 hours earlier. Andrew was understandably unsure and only had three of his eight crewmen aboard; the rest were ashore that night. Nevertheless, he set out right away. Townley told him to set his depth charges for 15 meters, likely to ensure they would explode if dropped in shallow water. This would give precious little time for the boat to get clear, however.

Nothing happened until 3:50, when Kanimbla, a British armed merchant cruiser, spotted what it thought was a submarine several hundred meters to the east of its stationary position northwest of Garden Island. This was far inside the torpedo net. About an hour later, the minesweeper Doomba reported a submarine sighting farther east, indicating Matsuo had turned around and was heading back to the mouth of the harbor.

The Japanese sailors’ luck ran out at 5 am, when Steady Hour and Sea Mist, joined by Yarroma, were patrolling near Taylor’s Bay on the northeast side of the harbor just inside the torpedo net. Sea Mist spotted a dark shape in the water, and Lieutenant Andrew moved in for a closer look. Andrew spotted the midget’s conning tower jutting above the surface.

It was Andrew’s first action and he was taken aback, describing it as a “shattering experience.” Years later, he said, “It caught me very much off guard and I was far from ready to deal with the situation.”

Despite his admission of distress at his first taste of combat, Andrew acted decisively. The submarine started submerging again. It seemed to have the same problem staying underwater as the other subs. Andrew fired a red flare, signaling nearby ships to stay clear of the area. He then ordered Sea Mist ahead at full speed, directly over the descending midget. He ordered the crew to drop a depth charge. The explosion threw up a wall of water, which lifted Sea Mist and flung it forward.

With a loud splashing noise, the midget sub popped out of the water. It was upside down and the stern jutted out, revealing its twin screws, now turning nothing but air. The submarine began to sink again, so Andrew dropped another depth charge. The blast threw Sea Mist about, and one of the engines was knocked out. Sea Mist could now only make five knots and was unable to continue the attack. Andrew withdrew, and Steady Hour and Yarroma moved in. For over three hours they dropped depth charges. At least 16 attacks were made.

The Japanese raid accomplished little; the tiny midget subs were clearly not up to the task of effectively attacking such a large and well-defended harbor. The Australians learned some harsh lessons about their preparedness at a cost of 21 lives and some damage to the ships and facilities within the port area. Despite warnings about submarines and the scouting flights by the Japanese floatplanes, nothing had been done to increase the security of the harbor.

Further, the initial response was slow. Lieutenant Eyers’s slow response to Cargill’s sighting was “deplorable and inexplicable,” wrote Admiral Muirhead-Gould in his official report.

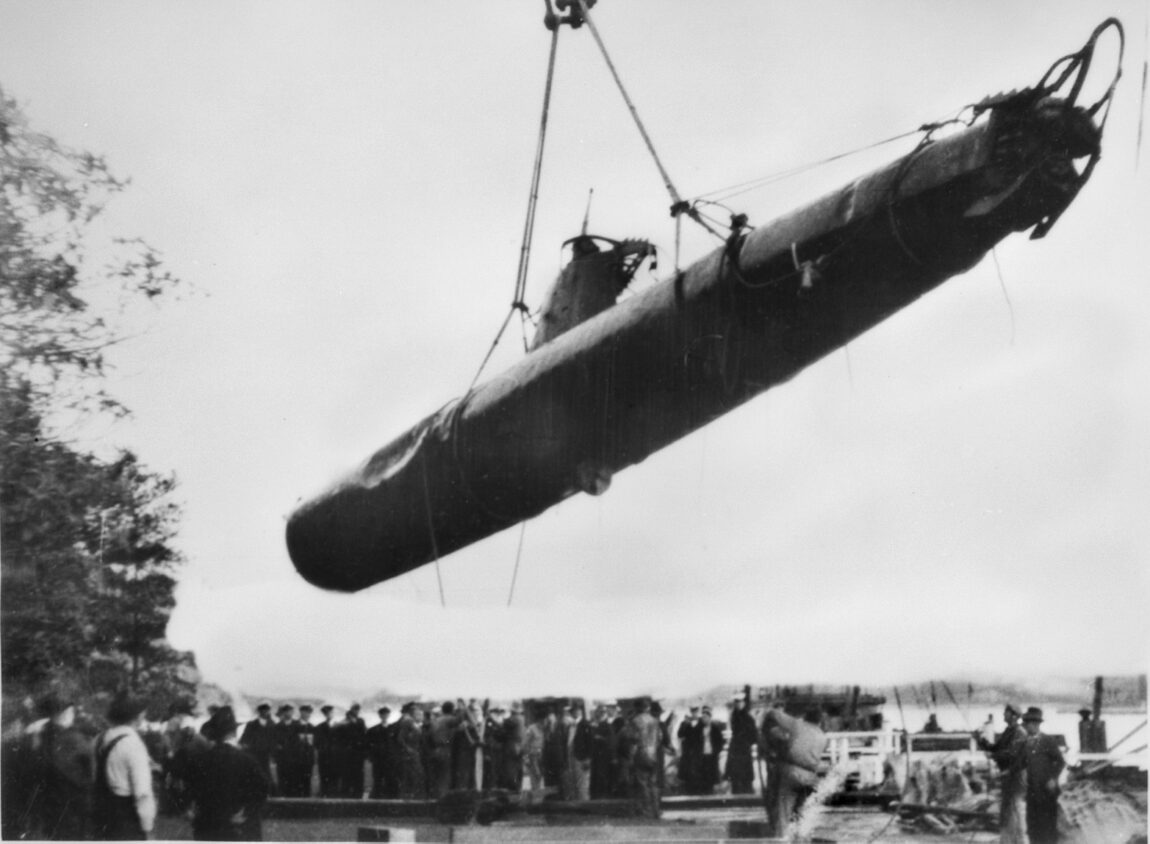

In the aftermath, the hulks of the destroyed midget submarines were raised from the bay’s floor. On the afternoon of Monday, June 1, divers found Matsuo’s sub resting at a depth of 18 meters. The twin screws were still turning slowly, and oil leaked from the hull. The torpedoes were still in their racks, and the steel cage over them was crumpled, preventing them from being launched or removed. The torpedoes needed to be disarmed, and this made recovery risky.

The sub was not brought to the surface until June 4. Crowds lined the shore as the wreck was hauled out of the water. Some were sailors, who removed their caps out of respect for the dead men inside. The sub was in two parts, requiring a second line to be attached. The bodies of both Japanese sailors were recovered. Each had a gunshot wound to the head, indicating suicide. Matsuo still wore his thousand stitch belt, and his sword was recovered. The remains were taken to the Sydney city morgue to await burial.

The day before, Chuma’s submarine was found still tangled in the net. The bow had broken off and sunk to the bottom. Divers dispatched to find it also recovered Japanese sailors’ bodies. The remains of Ban’s sub were discovered in November 2006 near the Northern Beaches, just a few miles northeast of Sydney Harbor.

On June 9, a funeral was held for the four Japanese sailors. They were cremated and buried with full military honors, including a salute of three volleys and Japanese naval ensigns draped across their coffins. Admiral Muirhead-Gould attended, accompanied by the Consul-General from the Swiss embassy. The event was covered by the local press, and the admiral was admonished by many at the time for allowing enemy combatants such honors of war. Muirhead-Gould defended his actions by recognizing the courage it took for anyone to attempt such a mission in a tiny submarine. It is also possible he and others in the Australian government thought the gesture might have a positive effect on Japanese treatment of Australian prisoners.

The ashes of the four sailors were later given to Tatsuo Kawai, the Japanese ambassador to Australia. He had been interned since the war began, but in August 1942 he was exchanged and sent home. Thousands of mourners greeted the ship carrying him on its arrival in Yokohama, including Matsuo’s former fiancée. He had broken their engagement before he left on his one-way mission.

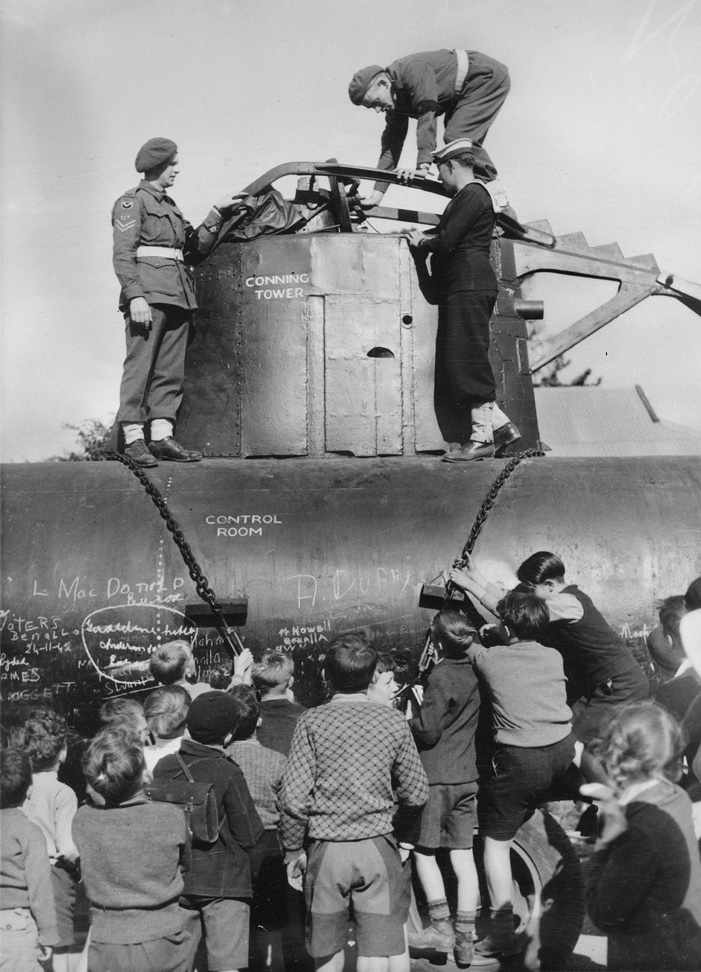

The Australian minister of the interior suggested displaying one of the submarines at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. Another group asked for a sub to be displayed to raise money for the Australian Comfort Fund, which provided relief items for Australians serving abroad. A single complete submarine was assembled using parts of the two recovered craft, and it was put on display at Bennelong Point, now the location of the famous Sydney Opera House. Admission was 20 cents, and reportedly a great deal of money was raised. Eventually the sub was taken on a tour of southeastern Australia.

Even more money was made selling postcards and models of the midget submarine. Today the sub sits on display at the Australian War Memorial along with other artifacts of the fateful night when Sydney harbor became the focus of Australia’s war for a brief few hours.

Christopher Miskimon is a regular contributor to WWII History. He is an officer in the Colorado National Guard’s 157th Regiment.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments