By Jiaxin Du

Most people think that World War II broke out on September 1, 1939, when the Wehrmacht crossed the German-Polish border. What many people do not know is that the Second Sino-Japanese War—an important part of World War II often overlooked by Western historians—actually started two years before the German invasion of Poland, and the Japanese invasion of Manchuria happened even earlier, in 1931.

The Battle of Beiping-Tianjin, which occurred from early July to early August 1937, was the first major campaign of the Second Sino-Japanese War; it also may be considered the first battle of World War II. Although it has great symbolic meaning, little information about this battle is available in English.

Beijing was not called “Beijing” in 1937 when the Second Sino-Japanese War unofficially broke out (in fact, this eight-year long bloody war never “officially” started, but that is another story). From 1911 to 1949, this historic metropolis in the Far East had quite a few different official names, resulting from political turbulence and military conflicts in China. By July 1937, this financial center and military stronghold of the Republic of China was actually called “Beiping,” which means “Northern Peace” in Chinese.

Because of its rich agriculture and highly developed industries, Manchuria was invaded first, and was one of the most important steps in Japan’s grand scheme of a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” With Manchuria occupied and a puppet state called Manchukuo established, Japan would have a forward base on the Asian mainland, either for further invasion of China and Southern Asia or for attacking the Soviet Union.

“First Internal Pacification, Then External Resistance”

When the Japanese invaded Manchuria in 1931, the Chinese military response was simply pathetic. Local warlords in Manchuria received instructions from the capital in Nanjing, or Nanking, not to escalate the conflict. Chinese calls for international sanctions against Japan were also refused by the League of Nations and the United States. The ineffectiveness and powerlessness of the League revealed in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria greatly encouraged other aggressors, namely Mussolini and Hitler.

Chinese appeasement was partly the result of the policy of “first internal pacification, then external resistance.” Jieshi Jiang, better known as Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of Guomindang, the Chinese Nationalist Party, also known as the Kuomintang, and his Chinese government had diverted too much attention to fighting civil wars. These wars were mainly against the Chinese Workers and Peasants Red Army, since many Chinese officials thought that Mao’s Communist guerrillas posed a more dangerous threat than the Imperial Japanese Army. Jiang once said, “The Japanese are a disease of the skin, while the Communists are a disease of the heart.”

Another reason why the Chinese government had been constantly trying to avoid war with Japan is that Jiang and his Nationalist government knew China, wrecked from two centuries of isolationism and the bloody warlord era that followed, was not capable of confronting Japan in any way. China was desperately trying to catch up with Japan in multiple areas. With the help of Germany under the Sino-German Cooperation, significant achievements in Chinese military, heavy industry, economy, and national defense had been made by the early 1930s, but that was not enough. Ironically, a large portion of the foreign aid for the Chinese to fight Japan in the first year of the war came from Nazi Germany, Japan’s ally. China needed time to prepare for full-scale war with Japan, and the Nationalist government was doing its best to earn as much as it could.

Following the invasion of Manchuria and the Battle of Rehe, the Imperial Japanese Army continued to encroach on Chinese territory, and the Chinese government was forced to sign a series of unequal treaties. On May 25, 1935, the He-Umezu Agreement was secretly reached between China and Japan. China recognized the “neutrality” of the eastern Hebei and Chahar provinces, the only geographical barrier between Japanese-controlled Manchuria and the Guomindang-controlled Northern China Plain to the south, though both provinces were already under Japanese occupation. Later that year, Japan officially established the East Hebei Anti-Communist Autonomous Council, turning the province of Hebei into a buffer state, and all Chinese forces in those areas were forced to withdraw south except for the 29th Route Army garrisoned in Beiping and Tianjin. By the end of 1936, all the areas north, east, and west of Beiping were controlled by Japan.

29th Route Army at Beiping-Tianjin

Since the beginning of 1936, the situation at Beiping-Tianjin had been constantly deteriorating. Tensions between the Chinese 29th Route Army and the Japanese China Garrison Army in this region were high. There had been numerous minor skirmishes but all ended in diplomatic negotiations.

The 29th Route Army of the Chinese National Revolutionary Army (NRA) was the only Chinese force left defending Beiping-Tianjin at the time. The Route Army was a Chinese military formation often consisting of more than one corps or many divisions. This formation type was later discarded during the war. The 29th Route Army was composed of four infantry divisions and two independent infantry brigades: the 37th Division, the 38th Division, the 132nd Division, the 143rd Division, the 39th Independent Brigade, and the 40th Independent Brigade. The Army also had the 9th Cavalry Division and the 13th Independent Cavalry Brigade, a Special Task Brigade, and the Hebei Peace Preservation Corps under its command. The total strength of the 29th Route Army was about 78,300 men.

Although they were poorly equipped compared to their Japanese counterparts, the Chinese soldiers were eager for battle and determined to defend their home country. The commander of the Army was General Second Class Zheyuan Song, a legendary general of the National Revolutionary Army who joined a warlord army at the age of 13 and graduated from Suiying Military Institute in Beijing (at that time the official name of Beiping was still Beijing). Song’s family was poor, and he grew up in squalor. Therefore, he was amiable to common people. Unlike many Chinese officials at the time, Song saw the Japanese as a more dangerous threat than the communists; he supported the establishment of the communists and the nationalists’ Second United Front against the Japanese, and he was highly praised by both the communists and the nationalists as a war hero. When he died in 1940 at the age of 56, Song was posthumously promoted to general first class, the Army rank second only to that of generalissimo, Jiang himself, and Mao wrote a eulogy for him.

The China Garrison Army

On the other side was the Japanese China Garrison Army (CGA) of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), formed on June 1, 1901, as part of Japan’s contribution to the international coalition in China during the Boxer Rebellion. The bulk of the China Garrison Army was the infantry brigade under the command of Masakasu Kawabe, with the 1st and 2nd Regiments stationed just outside Beiping and Tianjin, respectively, as foreign garrisons under the terms of the Boxer Protocol. In addition to the Kawabe brigade, the CGA also had an artillery regiment, a cavalry unit, an engineer unit, a signal unit, and a tank unit with 17 light tanks and tankettes. The total strength of the army was about 5,600, with Lt. Gen. Kanichiro Tashiro commanding.

Shortly after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, the IJA 5th and 20th Infantry Divisions from Japanese-occupied Korea, as well as the 1st and 11th Independent Mixed Brigades of the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria, reinforced the CGA, increasing the total number of Japanese troops in the vicinity of Beiping-Tianjin to approximately 80,000. The Japanese also had the support of the puppet Eastern Hebei Army. Although greatly outnumbered by the Chinese at first, these Japanese troops were well trained and well equipped; they also outgunned the Chinese with tanks and artillery and had complete air and sea supremacy.

On the Verge of War

Most of the tension in Hebei Province was focused on Marco Polo Bridge (also known as the Lugou Bridge), which was an 11-arch granite bridge across the Yongding River outside the historic town of Wanping Fortess, 15 kilometers southwest of Beiping. A modern railway bridge located to the north of Marco Polo Bridge was the choke point of the Pinghan Railway and the only available passage linking Beiping to the Guomindang-controlled Northern China Plain. The Japanese were aware of the Marco Polo Bridge’s strategic value and repeatedly demanded the withdrawal of all Chinese forces stationed in the area. The Chinese refused to give up the bridge and the fortress. The Japanese made plans to purchase nearby land to construct an airfield, which the Chinese firmly rejected.

Both the Chinese and the Japanese carried out intensive military maneuvers in the Beiping-Tianjin area, and the diplomatic situation between the two greatest powers in Asia worsened every day. It soon became common knowledge that no matter how appeasing the Chinese government was, a total war between China and Japan was on the verge of erupting.

The Marco Polo Incident Shatters the “Northern Peace”

On the night of July 7, 1937, the sound of gunshots shattered the “Northern Peace.” Unlike other minor conflicts, this one did not end in Chinese concessions. The next morning the eight-year Second Sino-Japanese War began. The estimated casualties are between 35 and 50 million.

There have long been controversies over whether the Marco Polo Bridge Incident was an accident or a deliberately planned attack by the Japanese, since it marks the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

As the situation in China deteriorated, the Japanese routinely held military exercises in the vicinity of Wanping, but normally with advance notice so the local inhabitants would not be disturbed. On July 7, 1937, around 7 pm, night maneuvers were carried out by the 8th Company, 3rd Battalion, CGA 1st Infantry Regiment without prior notice, alarming the local Chinese forces.

The Chinese force guarding the Marco Polo Bridge that night was the 219th Infantry Regiment, 37th Division, 29th Route Army. According to the Chinese, the commanding officer of the 219th Regiment, Xingwen Ji, received a telephone message from the Japanese after their exercise was finished. The Japanese claimed that Private Kikujiro Shimura was missing and they suspected that he had been abducted by the Chinese. In fact, he was lost on his way back from the exercise and found his way to his unit hours later. The Japanese troops demanded permission to enter Wanping to investigate. Colonel Ji refused. Letting Japanese soldiers into Wanping at night would greatly disturb the civilians and cause panic. In addition, Colonel Ji never trusted the Japanese and knew they had fabricated several similar incidents before in order to encroach on Chinese territory. At about 5:30 am on July 8, the Japanese began shelling the bridge and Wanping, and an assault on the Chinese position around Wanping was launched.

Japan had a different version of the story at the time. According to the announcement made by the Imperial Japanese Army in 1937, ineffectual rifle shots were fired first by the Chinese after the military exercise had ended; suspicious flashlight signals were also detected on the Chinese position. In addition, one Japanese soldier, Private Kikujiro Shimura, was reported missing. With all this happening, battalion commander Major Kiyonao Ichiki and regimental commander Colonel Renya Mutaguchi of the CGA thought that a Chinese attack was underway and ordered their troops to heightened alert. A team was sent to investigate the incident with the Chinese. However, Chinese forces had already begun shelling Japanese positions with mortars before the team arrived. The Japanese did not retaliate at first but finally returned fire at 5:30 on the morning of July 8.

The Chinese version of this story is more believable and is accepted by most historians and scholars today. However, some people still believe the incident was unintentional. Some ultra-conservative historians even believe that the incident was staged by the Chinese Communists, who hoped it would lead to a war of attrition between the Japanese and the Guomingdang, which actually did happen.

Holding the Marco Polo Bridge

Although there are disputes over the cause of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, subsequent events are clear. At 11:40 pm on July 7, shortly after Colonel Ji refused Japanese demands to enter Wanping, Lt. Gen. Dechun Qin, acting commander of the 29th Route Army, mayor of Beiping, and chairman of the Hebei-Chahar Political Council, was contacted by Japanese military intelligence with the same demand. Qin also refused but agreed to order Chinese troops stationed at Wanping to conduct a search with attached Japanese officers. The Japanese were satisfied with the reply. The situation did not ease. Sporadic shots were exchanged, and both the Chinese and Japanese rushed reinforcements to the area. Around 5 am the next day, the Japanese 1st Infantry Regiment launched an assault on Chinese positions around Wanping and the Marco Polo Bridge, breaking the agreement made earlier.

With little effective resistance encountered, the 7th and 8th Companies of the CGA 1st Infantry Regiment quickly breached the Chinese defensive line along the eastern shore of the Yongding River north of Wanping. The Japanese crossed the river and continued their attack on the western shore, conducting a flanking maneuver to the southwest after landing in an effort to surround Wanping. After successfully outflanking Wanping and the Marco Polo Bridge, the Japanese attacked the bridge from the rear. Colonel Xingwen Ji led the Chinese defenses with about 100 men and was ordered to hold the bridge at all costs. Much to Japanese surprise, the Chinese uncharacteristically fought with determination. By the afternoon, the Japanese had managed to occupy only the southern end of the bridge. On the morning of July 9, the reinforced Chinese retook the bridge with the help of mist and rain.

A Fragile Cease-Fire

The conflict had reached a stalemate by the morning of July 9, and Chinese and Japanese officials went back to the negotiating table.

A verbal cease-fire agreement was reached that day. If the Japanese had honored their promise and the cease-fire had remained in place, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident would have ended as just one of the numerous minor skirmishes between the Chinese and Japanese in the mid-1930s. However, this incident seemed destined to escalate.The truce was broken only two hours later when the Japanese started shelling Wanping. For the next two days, the Japanese provoked four minor skirmishes, completely disregarding the cease-fire. However, the Chinese had also violated the agreement by mobilizing reinforcements.

On July 10, the Japanese unilaterally tore up the agreement they had made a day earlier and demanded a new one. Although the Chinese agreed to the terms demanded by the Japanese and began a new round of negotiations, the CGA did not reduce its belligerence. In fact, while the Chinese were still trying to defuse the tension and localize the conflict, the Japanese had begun to mobilize the Kwantung Army.

A more formal agreement was reached on July 11 between Lt. Gen. Dechun Qin, acting commander of the 29th Route Army, and Takuro Matsui from Japanese military intelligence. According to the agreement, the Chinese acquiesced to the fact that the Japanese now had control of the eastern shore of the Yongding River. The Japanese would occupy the eastern shore while the Chinese would maintain control of the western shore. Furthermore, the agreement stipulated that the defensive position of Colonel Ji’s 219th Regiment would be turned over to the Peace Preservation Corps. In exchange, the Chinese demanded that Japanese troops on the western shore be withdrawn and return to the now Japanese-controlled eastern shore. They also demanded the withdrawal of all Japanese reinforcements that moved into the vicinity of Wanping after the conflict had escalated.

However, both the Japanese and Chinese violated the terms of the agreement. The Japanese were simply using the truce as a ploy to distract the Chinese, and General Qin was trying to localize the situation and calm the Japanese down since he was only the acting commander and did not want to worsen the situation. General Zheyuan Song, the commander in chief, was already on his way back to his post from a vacation.

The China Incident in the Japanese War Camp

There had been conflicting opinions within the Japanese government over the topic of Japanese aggression in China. The Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office, the Army Ministry of Japan, the Kwantung Army, and the civil government all had different visions for the China Incident. Complicating the situation, the Japanese Army itself lacked a central authority to decide what policy to follow.

On July 11, the day the agreement was reached between Qin and Matsui, Japanese War Minister Hajime Sugiyama proposed preliminary measures for the mobilization of the Imperial Japanese Army and the establishment of a Temporary China Area Aviation Division to reinforce the Japanese China Garrison Army, which had only 5,600 men. The cabinet approved his proposal partly because a rejection might cause the powerful war minister’s resentment and thus the collapse of the Konoye Cabinet, which was only 37 days old.

Japanese militarists promised that even if a war broke out the feeble Chinese Army would pose no threat. Generals in Tokyo even assured the emperor that China would be defeated within three months.

Holding Ground Against the Foreign Invaders

On the Chinese side, General Zheyuan Song finally returned to Tianjin on July 11 carrying an order from Generalissimo Jiang to defend Chinese soil at all costs. Although many senior officers suggested a preemptive strike before the arrival of Japanese reinforcements, Song had something else in mind.

Like many Chinese generals at the time, Song had a strong ideal of warlordism and tended to analyze the situation from a more political point of view rather than purely military. Despite the superficial unification of China under the rule of the central Nationalist government, warlordism in China did not end. Although the warlords had submitted to the central government and claimed allegiance, there were still conflicts between the former cliques and warlord armies.

Since both he and his 29th Route Army were remnants of the Northwestern Army (one of the many military factions founded during the Warlord Era), Song knew well that he could never rely on the central Nationalist government and its elite German-trained divisions to reinforce him. He also had no confidence in the other former warlord armies around him. It was likely that he would have to fight the Japanese by himself.

This time Generalissimo Jiang did not follow his usual policy of “first internal pacification, then external resistance.” In contrast, he told Song to hold his ground against foreign invaders at all costs. Song suspected, with a good deal of justification, that this might be Jiang’s plan to allow the Japanese to crush his army. Jiang had long wanted to solve the warlord problem and had destroyed several other former warlords using similar methods. Song knew that the ill-equipped 29th was no match for the Japanese if a full-scale war broke out. He might win a few battles but not the entire campaign. In the end, his army would be utterly crushed. An army is the most important organ to a warlord, and without the 29th Zheyuan Song would become nothing more than a puppet in the high command of the NRA.

Song vetoed a preemptive attack, still believing that it was possible to make peace with the Japanese, even by giving away certain territories. Sadly, things did not go his way, and his hesitation only made the situation worse.

Unofficial Declaration of War on Japan

On July 12, Lt. Gen. Kanichiro Tashiro, commander of the CGA, suddenly fell ill. He was replaced by Lt. Gen. Kiyoshi Katsuki, one of the many old China hands in the IJA. On July 14, the Japanese shelled Wanping.

On July 15, a plan for a major offensive against Beiping-Tianjin was finalized. Since Japanese troops already controlled the areas north, east, and west of Beiping, this offensive was focused on the southern flank. Doing so would cut Beiping off from the rest of the Guomindang-controlled areas in the south and encircle the Chinese forces. General Katsuki ordered all his troops to be in position by July 20. Later that day, Lt. Gen. Kanichiro Tashiro, former commander of the CGA, died of a heart attack, becoming the first Japanese general to die in the Second Sino-Japanese War.

On July 17, Jiang made his famous Lushan Statement, unofficially declaring war on Japan. On the same day, Song held negotiations with the new Japanese commander, Kiyoshi Katsuki, while officials from the two sides were also meeting in Nanjing. The 1st Independent Mixed Brigade of the Kwantung Army reinforced the CGA.

On July 18, the 20th Division reinforced the CGA, and the following day the negotiations between Song and Katsuki ended in failure. The 11th Independent Mixed Brigade reinforced the CGA, and on July 20, the Japanese shelled Wanping again, wounding Colonel Xinwen Ji.

The Tongzhou Incident

On July 25, with the arrival of new supplies, the Japanese launched another offensive. The 77th Regiment of the CGA 20th Division and the 226th Regiment of the NRA 38th Division clashed in Langfang, a small city between Beiping and Tianjin.

Japanese forces occupied Langfang the following day along with all the transportation hubs along the railroad linking Beiping and Tianjin, severing connections between the cities. In the evening, the 1st Regiment of the CGA attempted an assault on the Guangan Gate in Beipin but was repelled by the Chinese. An ultimatum was issued to Song demanding the withdrawal of all Chinese troops in Beiping within 24 hours (the deadline was later extended to July 28), or Japanese troops would “act freely.”

After negotiations with the Chinese had failed, conservatives in the Japanese government were still trying to ameliorate the situation. However, their efforts ended in vain on July 29, with the Tongzhou Incident. A unit of the Japanese collaborationist Eastern Hebei Army defected to the Chinese in the town of Tongzhou, murdering many Japanese officers and civilians in the process.

Early on the morning of July 27, units of the CGA 2nd Regiment laid siege to the 1st Battalion, 2nd Regiment, NRA 39th Independent Brigade guarding Tongzhou. During the battle, disputes broke out between the Japanese forces and the collaborationist Eastern Hebei Army, and this led to the bloody Tongzhou Incident. Japanese forces also conquered many other Chinese positions outside Beiping. Chinese troops that managed to break out retreated to Nanyuan barracks, a military stronghold south of Beiping and headquarters of the 29th Route Army.

Finally acknowledging that war was inevitable, Song rebuffed the ultimatum issued by the Japanese and ordered all units of the 29th Route Army mobilized. Song also requested assistance from Generalissimo Jiang and other former warlords in the area, but just as he had expected no reinforcements ever arrived.

Japanese Offensive Against Beiping

The Japanese launched their major offensive against Beiping at dawn on July 28. Katsuki’s plan was to attack from the south with the IJA 20th Division and the CGA 1st Regiment; the two independent brigades from the Kwantung Army were deployed north of Beiping, containing Chinese forces in that area.

The offensive was concentrated on Nanyuan barracks with a secondary attack on Beiyuan north of Beiping. Backed by close artillery support, the 20th Division and the 1st Regiment mounted a frontal assault on Nanyuan.

The fighting for Nanyuan was the bloodiest and most intense of the entire Battle of Beiping-Tianjin. Soldiers from both sides fought with great determination, and positions changed hands several times.

With information provided by Chinese traitor Yuguio Pan, the Chinese troop deployment and plans for counteroffensives were at Katsuki’s fingertips. Katsuki’s first targets were two regiments of Dengyu Zhao’s 132nd Division still on their way to Nanyuan. With the help of Yugui Pan, the Japanese launched a successful ambush near Tuanhe and completely destroyed the Chinese regiments. Zhao led the third regiment to rescue the rest of his division only to be repelled by the Japanese.

The Nanyuan barracks was surrounded by a brick wall, and the first line of Chinese defense was set right outside it. At dawn on July 28, Japanese artillery turned the brick wall into debris and soldiers from the 3rd Battalion, CGA 1st Infantry Regiment under the command of Ichiki charged into the weakest spot of the Chinese line, where student soldiers were positioned.

The regiment included 1,700 students from local universities and high schools, who were receiving military training at the time. Mostly teenagers, they had been given their rifles a few hours earlier. The Japanese, thinking that they could capture the barracks easily, were greatly surprised by their opponents’ dogged determination later in the fight.

Charging Into Land Mines

Japanese soldiers encountered little initial resistance as they charged toward Chinese positions. However, the attack did not go the way the Japanese had planned. Ichiki’s men encountered a minefield in front of the Chinese position, slowing them considerably.

Ichiki later recalled in his First Anniversary Symposium of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1938, “There was great confusion at the time. The artillery coordinator beside me was dumbfounded. He kept shouting into his telephone, ‘Too close! Too close!’ He thought the explosion [of the mines] was our own artillery hitting too close.”

However, the mines did not stop the Japanese. With unbelievable stubbornness, Ichiki’s men managed to break through, rushing into the Chinese positions. The Chinese students, driven by great patriotism and nationalism, were as determined as the Japanese.

Jiecheng Ruan, a student from Zhicheng High School, was a student soldier at the time. Seventy years later, he remembered every detail of that day: “Each student received an old rifle with 200 rounds, four grenades, and a big saber. Everyone in the 29th had a big-saber…. Many of us had never touched a gun before…. I saw a Japanese in the distance and I fired, didn’t even aim. God knew where the bullet had gone.”

As the Japanese poured into Chinese trenches, a hand-to-hand melee broke out between the opposing forces. The students fought desperately but were no match for the Japanese soldiers, who were masters of close combat. Although the Chinese managed to hold their positions with great determination, the cost was devastating. The student-soldiers lost 10 of their number for every Japanese soldier killed or wounded. The tremendous sacrifice of the Chinese students stopped the Japanese only for a few hours.

The First Japanese Correspondent Killed in the War

A little surprised at the failure of Ichiki’s first assault, Lt. Gen. Bunzaburo Kawagishi took over the assault with his newly arrived IJA 20th Division and sent the CGA 1st Regiment north to cut off Nanyuan from Beiping. Kawagishi mounted his second assault at 8 am, just after Dengyu Zhao and his regiment returned to Nanyuan from their unsuccessful rescue mission. The second assault was more organized, cautious and, with close air support, much more furious. The Chinese forces lacked antiaircraft weapons and suffered heavy casualties from Japanese bombers. Kawagishi noted this weakness and intensified the air attacks.

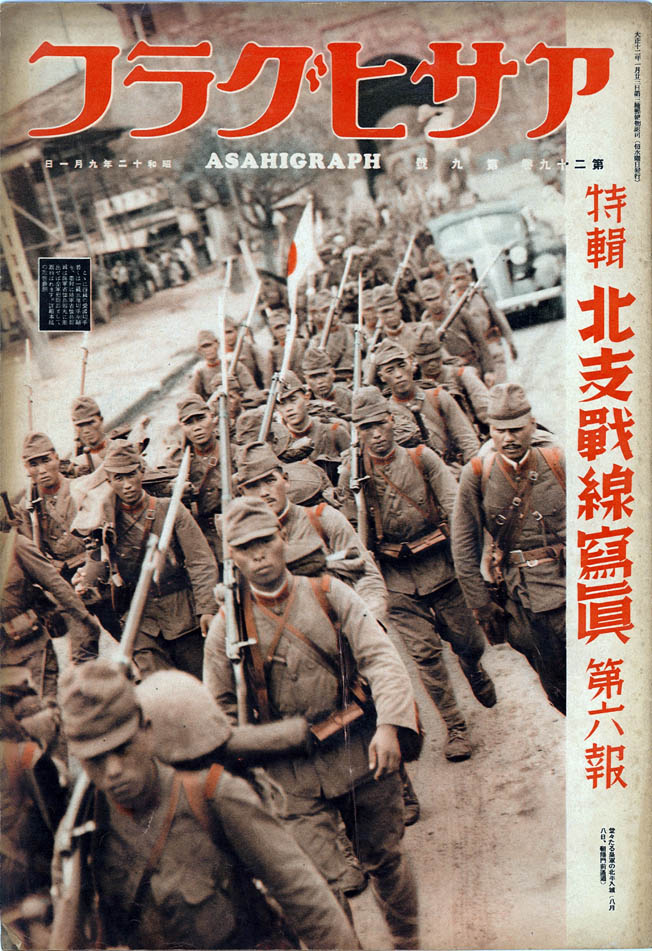

With their communication system destroyed, the Chinese now found themselves in absolute disarray. Some Chinese soldiers tried in vain to shoot down Japanese aircraft with their rifles but were killed by the strafing Japanese fighters. Japanese forces breached the Chinese defenses in many sections, and chaotic firefights and hand-to-hand combat soon followed. During the fighting, Magoshiro Okabe, a famous Japanese war correspondent from the Asahi Shimbun newspaper was killed. He was the first Japanese war correspondent killed in the Second Sino-Japanese War and the first nonmilitary person to be enshrined at the Yasukuni Shrine.

Meanwhile, the CGA 1st Regiment had maneuvered to the vicinity of Dahongmen. Traitor Pan was certain that Dahongmen was where the Chinese forces in Nanyuan would assemble after retreating; this was confirmed by another Chinese traitor. The CGA 2nd Regiment was also sent into this area. The Japanese had decided to lay an ambush.

A Catastrophic Japanese Ambush

Back in Nanyuan, the Chinese repulsed the second Japanese assault after a furious battle but suffered heavy casualties. The regiment of student soldiers had dwindled to 800. At 1 pm, Dengyu Zhao, the commander in chief of the Chinese forces in Nanyuan, received the order from Song to break out and retreat to Beiping.

Later that day, a column of Chinese soldiers was ambushed by the Japanese near Dahongmen, and the one-sided battle soon turned into a massacre.

Lieutenant General Dengyu Zhao, commander of the NRA 132nd Division and Lt. Gen. Linge Tong, deputy commander of the NRA 29th Army, were both killed in the battle. According to Japanese wartime archives, Japanese soldiers found Zhao’s body sitting on the back seat of his bullet-riddled car after the battle, with fatal wounds to his chest and forehead. Tong was killed leading his men in an attempt to fight their way out of the ambush. Fewer than 2,000 of the 7,000 men in the Chinese garrison in Nanyuan made their way back to Beiping.

The book History of the Continental War, published by Japanese Army Pictorial in 1941, contains a vivid description of the aftermath of the Battle of Nanyuan. “The Battle of Nanyuan had finally come to an end; our sacrifice was tremendous, but we finally conquered the enemy fortification in the afternoon [of 28 July]. The wind had stopped, the soldiers bathed in the sunlight. Ragged clouds adorned the empty sky, while countless bodies of the dead dotted the ground. This was a nightmare under bright daylight.”

“Attack Cancelled”

On July 28, a column of Chinese soldiers from the 219th Regiment was marching toward the Marco Polo Bridge. Just a few weeks earlier they had fired the first shots of the Second Sino-Japanese War on Marco Polo Bridge, and now they were eager to take it back from the Japanese. Just when the soldiers were preparing for their counterattack, an officer from the 110th Brigade arrived with a simple order: “Attack cancelled. The 219th will turn back immediately and retreat.” Many were shocked by this order since they had no idea what had happened at Nanyuan.

On the same day, a brigade of the NRA 38th Division pushed back the Japanese in the Langfang area; units of the NRA 37th Division also launched a counterattack on Fengtai but were repulsed by the Japanese. The two independent brigades from the Japanese Kwantung Army in the north conquered the towns of Shahe and Qinghe.

A Controversial Secret Mission

With the stronghold of Nanyuan and two of his best generals lost, General Song acknowledged that the battle was as good as lost and any further resistance would be futile. The Generalissimo also noted the gravity of the situation and ordered Song to withdraw. By nightfall, Song abandoned Beiping and withdrew the bulk of his army to Baoding. The 27th Independent Brigade of the NRA 132nd Division was the only Chinese unit left in the city to maintain public order. Zizhong Zhang, mayor of Tianjin and commander of the 38th Division, was left in Beiping to take charge of political affairs and the aftermath of the fighting. His secret mission was to negotiate with the Japanese, buying time for Song to safely assemble his army.

Zhang’s mission would surely make him a target of public criticism, and he, a resolute patriot, would be misunderstood as having defected to the Japanese. Dechun Qin later wrote in his book Zizhong Zhang and I that Zhang bade farewell to him in tears that night, saying, “You and Mr. Song will become heroes, but I am going to be blamed as a traitor from now on!”

Beiping-Tianjin Falls to the Japanese

At 8 am on July 29, the 11th Independent Mixed Brigade of the Kwantung Army attacked Chinese positions near Huangsi and Beiyuan. The Hebei Peace Preservation Corps defending Huangsi withdrew at 6 pm. The 39th Independent Brigade defending Beiyuan was disarmed by the Japanese two days later. Beiping soon fell to the Japanese. General Masakazu Kawabe, commander of the CGA Brigade, entered the city on August 8 in a military parade in which the citizens of Beiping were forced to celebrate.

At dawn on July 29, the IJA 5th Division and Japanese marines attacked Tianjin and the port of Tanggu, defended by Chinese units of the 38th Division. The Chinese soldiers and many local volunteers fought gallantly. They even managed to capture the Tianjin Station from the Japanese. The 38th Division mounted a series of counterattacks on the Japanese headquarters at Haiguangsi and the Dongjuzi airport. However, the Japanese were able to repulse the Chinese counterattacks with artillery and air support. After heavy fighting, Tianjin fell to the Japanese on July 30.

On July 31, the 27th Independent Brigade managed to break out of Beiping to Chahar and returned to the NRA 143rd Division. That same day, Japanese forces finally conquered the entirety of Beiping-Tianjin by capturing the last Chinese positions near Dahuichang.

The Battle of Beiping-Tianjin had ended, but a full-scale war had now erupted between China and Japan.

Strong malevolence still exists between China and Japan, and the people of these countries are still living in the shadow of one of the greatest calamities in human history.

Author Jiaxin Du is a first-time contributor to WWII History. He resides in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments