By Steven M. Johnson

The waters of the South China Sea shimmered in the sunlight on the morning of April 15, 1847. In a gradual manner, with several more vessels arriving at a time so as not to draw the attention of lookouts on nearby French ships, a small Annamese fleet assembled in the bay at Tourane. The Annamese sailors had camouflaged their guns so the French would remain unaware that they posed a threat for as long as possible.

The two French warships, the 54-gun frigate Gloire, commanded by Captain Augustin de Lapierre, and the 24-gun corvette Victorieuse, under the direction of Captain Charles de Genouilly, had been dispatched by Paris to negotiate for the release of Jesuit priest Dominique Lefebure and other Catholic missionaries imprisoned by the Annamese and to lobby for more tolerance toward those seeking to worship as Catholics in Annam.

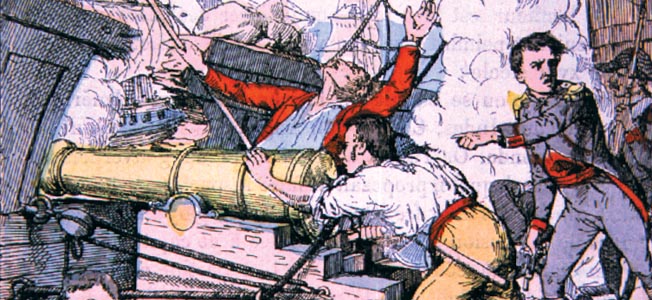

Suddenly a swarm of vessels, the largest of which were five corvettes, sailed toward the French ships. The sailors aboard the Annamese corvettes unmasked their guns and fired on the French ships. The shells crashed into the sides of the ships and wreaked havoc on their decks. In response, French sailors sprang to their guns and returned fire.

Despite their numbers, the Annamese were greatly outmatched by the professional crews of the French ships. As the battle progressed, it was apparent that all the Annamese could do was annoy the superior ships. That harassment came with a heavy price as the French, before the day was done, destroyed all of the corvettes and many smaller junks that had supported the attack.

Unfortunately, the French ships were no longer safe at anchor off Tourane, and their captains put to sea without having succeeded in their political aims of gaining the release of Lefebure and other missionaries. Unknown to the commanders of the ships, Lefebure had already been released and made his way out of Annam to Singapore. Nevertheless, the persecution of Catholic missionaries continued. The Annamese were intensely hostile to their efforts, and killing and torturing missionaries was a routine occurrence.

The action at Tourane brought the French one step closer to upping the ante from the mere presence of missionaries in Annam and adjacent regions to conquering them and transforming them into colonies.

Thieu Tri’s Suppression of the Catholics

The debacle surrounding U.S. involvement in Vietnam never would have happened had France not sent Catholic missionaries to Annam and Cochinchina (southern Vietnam) in the 1600s to convert the Vietnamese to Christianity. The persecution of French missionaries in the 1800s then gave Napoleon III the excuse that he needed to send troops to claim Indochina at first as a protectorate and then later as a colony of France. It was the defeat of France in 1954 that caused French Indochina to be split into Cambodia, Laos, communist North Vietnam, and democratic South Vietnam and set the stage for the eventual entry of the United States into the Vietnam War.

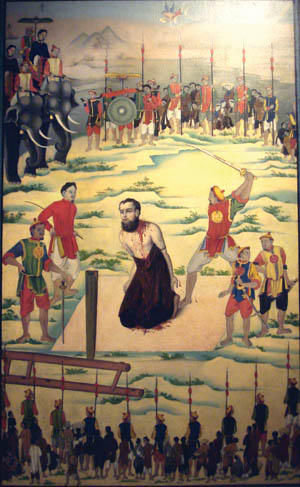

France had sent Jesuit missionaries in 1627 to join Portuguese missionaries in converting the Vietnamese and Cambodians to Catholicism. By 1664, the French Jesuits had completely taken control of missions in Indochina. French missionaries did most of the early exploring and mapping of Indochina in the 1600s and 1700s. In 1799, the French priest Pigneau de Be’haine led an army of mercenaries to help Nguyen Anh take the throne as emperor of Annam. Pigneau did this in the false belief that Nguyen Anh would show the French favor to gain influence and to possibly begin the role of protectorate over Annam. Instead, Nguyen Anh was suspicious that the French missionary presence and aid had more sinister motives. Between 1825 and 1842, the persecution of French missionaries increased with seven priests being tortured to death. In 1843, the French sent a fleet to rescue a number of missionaries and to maintain a permanent presence in Indochina.

In 1844, Lefebure plotted to replace the Vietnamese emperor, Thieu Tri, for an emperor more receptive to Christianity. The plot was foiled, and Lefebure was imprisoned amid the protests of the French government. Thieu Tri released Lefebure in March 1847, in fear of some form of military retaliation by the French government.

Tu Duc succeeded Thieu Tri in 1847 as emperor of Annam and Cochinchina. Tu Duc had a bitter hatred for the French missionaries and their Vietnamese converts and embarked on a fierce campaign to eliminate Christianity from Vietnam. Vietnamese Catholics were to be branded with the word “ta doo” (infidel) on their left cheek, and all of their property was to be confiscated by the state. French priests were to be drowned and Vietnamese priests were to be sawed in half lengthwise. In 1851 and 1852, two prominent priests were put to death, and missionaries all over Asia called for action by the French government.

Napoleon III’s Expedition to Indochina

Napoleon III came to power in a coup d’etat with the support of the church in 1852. Thus he could not escape a commitment to missionary goals in Asia. He also had his own ambitions to gain expansionist glory as his illustrious uncle had. Napoleon III was reluctant to act at first for fear of reprisals against missionaries in interior areas of Indochina, but finally in 1856, he endorsed a plan to capture the city of Tourane from Annam. Napoleon III had mistakenly believed that the French would be welcomed as liberators from an oppressive emperor.

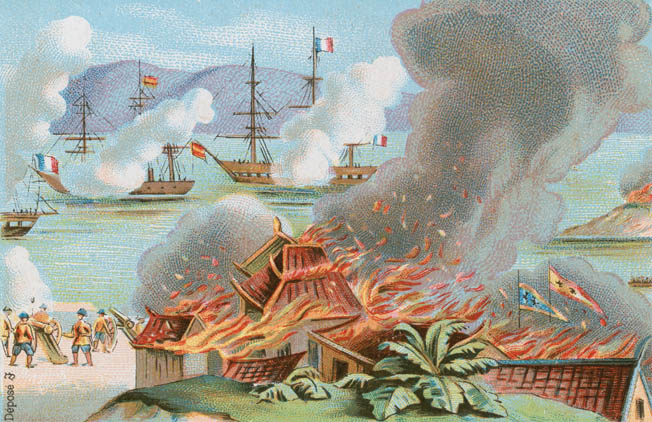

In 1858, a force of 2,500 French foreign legionnaires and 500 Spanish troops began their conquest of Indochina by occupying Tourane and using it as a base for future operations. The French legionnaires and Spanish troops found that the Vietnamese troops would not fight them in pitched battles but withdrew into the jungle and set ambushes on small groups of French troops who left Tourane to scout or patrol around the city. Many French troops suffered crippling wounds from falling into covered pits with sharpened bamboo stakes covered in dung that impaled feet and often caused death from gangrene infection.

These guerrilla tactics would haunt the French and then the Americans for more than 100 years and prove difficult to counter. French soldiers,outfitted in their heavy uniforms, also struggled in the searing sun and torrential monsoon rains. After six months of occupation, the French army was losing hundreds of men to ambushes and diseases such as cholera, malaria, dysentery, and gangrene. Napoleon III’s glorious expedition was turning into a disaster.

The Siege of Saigon Begins

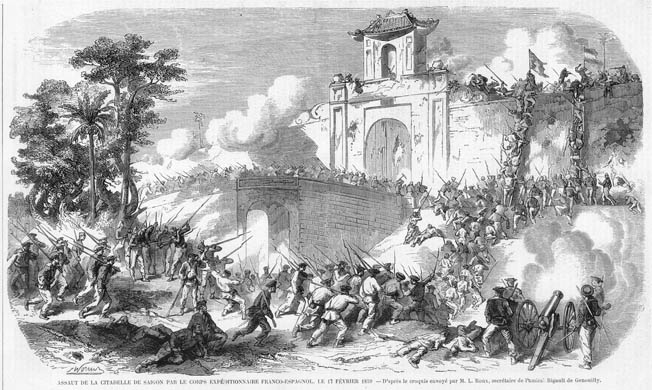

Unable to make any progress in Tourane, the French looked to Saigon in southern Cochinchina. Saigon, a town with more than 2,000 inhabitants, was an important trading center that was protected by a strong citadel. On February 16, 1859, a flotilla of French warships began exchanging cannon fire with the Vietnamese citadel and eventually blasted a small breach in the northeast wall. Two companies of French marines and sailors landed and charged the citadel breach, which was widened by explosives laid under fire by some accompanying sappers. The column then scrambled up the rubble in the breach and into the citadel with bayonets. The Vietnamese fought briefly but then melted into Saigon and the surrounding jungle.

Although the French and Spanish troops controlled Saigon they could not venture outside the town without losing men to ambush or booby traps. The French commander, Admiral de Genouilly, left 1,000 French troops to garrison Saigon and returned to Tourane, where he found that the garrison had lost several hundred more men from tropical diseases. De Genouilly decided to abandon Tourane and took the remainder of his troops to join a British invasion of northern China in the Second Opium War.

[text_ad]

In 1859 and 1860, Emperor Tu Duc sent a Vietnamese army of 12,000 to begin digging trench lines toward French positions and the citadel at Saigon. The siege turned Saigon into a hellhole for the French forces left there. Both sides sortied to disrupt the other side’s entrenchments. On December 7, 1860, more than 1,000 screaming sword-, pike-, and halberd-wielding Vietnamese troops sortied against French entrenchments near the Khai Tuong Pagoda, decapitated one of the foreign legion commanders, and caused more than 100 casualties in a desperate action that was eventually repulsed by French bayonets.

Breaking the Ky Hoa Fort Complex

The siege of Saigon had lasted for more than a year when Vice Admiral Leonard Charner brought 3,000 French marines and naval infantry with 270 Spanish troops to Saigon in January 1861 to relieve the siege. The Vietnamese had been reinforced to close to 30,000 troops and had built more than 12 kilometers of entrenchments and redoubts with thousands of pits and ditches around the French fortifications at Saigon.

The centerpiece of the Vietnamese defenses was the Ky Hoa fort complex, which consisted of five fortifications with connecting walls fronted by a redoubt. The complex sat a kilometer outside the French fortifications at Saigon. On February 24, 1861, a French column supported by gunboats on the Saigon River assaulted and took a redoubt at bayonet point in front of the Ky Hoa forts at the cost of six dead and 20 wounded. Many of the French wounded had been pierced through the feet by dung-covered bamboo stakes and were in great agony. The Vietnamese launched a counterattack to retake the redoubt with several thousand troops and a number of war elephants with swivel guns on their top castles. French rifle fire with army and gunboat artillery killed and wounded hundreds of Vietnamese and most of the elephants before they turned back.

On February 25, the French brought artillery to the redoubt to support an attack on the Ky Hoa forts by 1,200 marines supported by 600 French and Spanish troops. The Vietnamese fire was heavy especially just under the forts’ earthen walls, and the French took heavy casualties. After a half hour, the French managed to mount the fort’s ramparts with grenades, grappling hooks, and the only three ladders to have made it intact to the walls. The Vietnamese fought viciously but were no real match for the larger, stronger French troops with their 19-inch bayonets.

After the Vietnamese fell back, the French started taking heavy casualties from Vietnamese artillery from the Mandarin Fort, which sat 100 meters back in the middle of the Ky Hoa fort system. The French troops had no cover from the artillery fire and had no choice but to charge the Mandarin Fort as well. Many French troops were shot and dismembered in a hurricane of bullets, cannonballs, and grapeshot as they tried to bring up grappling hooks, ladders, and sappers to find a way into the fort. The French reserve was then brought up through the maelstrom and breached the main gate to the Mandarin Fort with axes and hatchets. The French troops charged through the gate and killed more than 300 Vietnamese troops inside before the entire Vietnamese army broke and retreated from its entrenchments around Saigon.

The assault on the Mandarin Fort cost the French another 225 casualties. Emperor Tu Duc’s power was broken as the French then occupied all six provinces of Cochinchina. In 1862, a treaty was signed with Napoleon III that made Vietnam a protectorate of France in return for allowing Tu Duc to remain as a puppet ruler. Spain decided to end its involvement in Cochinchina because the region seemed to be a quagmire and France seemed to have more in mind than just saving missionaries.

Black Flags in Hanoi

The French and Vietnamese experienced peace for the next 10 years as the French explored and mapped Indochina. In 1870, Napoleon III was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War and removed from power. The loss was so humiliating that France sought to regain its nationalistic pride and respect by extending its power into Africa and especially Indochina, since there were no French colonies in Asia.

In 1873, a French merchant by the name of Jean Dupuis began a daring enterprise to open the Red River in Tonkin to French trade without the knowledge of the French government. Dupuis hired a mercenary force of 200 armed Europeans, Filipinos, and Chinese to open trade in northern Vietnam. Dupuis and his mercenaries began by assaulting Hanoi and raising the French flag over part of the city, which was against the treaty that had been signed between Napoleon III and Tu Duc. Dupuis appealed to the French military in Saigon for reinforcements because he and his small force of mercenaries were in an untenable position in Hanoi with thousands of Vietnamese troops gathering near the Hanoi citadel. Several hundred French troops were sent under Francis Garnier, who stormed the Hanoi citadel as the Vietnamese forces fled. Garnier then went on to conquer the area from Hanoi to the Gulf of Tonkin against Emperor Tu Duc’s protests.

The French attacks had set the whole Tonkin area into chaos. The Taiping Rebellion, which convulsed China from 1853 to 1868 and cost 30 million lives before being put down by Chinese government forces, drove thousands of Taiping insurgents into Vietnam. Once in the region, they joined a powerful Chinese bandit and pirate army called the Black Flags. The Black Flags proceeded to plunder defenseless villages and to commit piracy along the Tonkin and in the rivers of northern Vietnam in the 1860s and 1870s. Tu Duc appealed to China for help, and that country sent an army that simply deserted and joined the Black Flags, which had the real power along the Chinese and Vietnamese border areas.

Tu Duc then appealed to the Black Flags for help in ejecting the French from Hanoi. On December 21, 1873, several thousand Black Flag troops brought up cannon that blasted open the front gate to the Hanoi citadel. Dupuis and his mercenaries were subsequently massacred by the Black Flag forces. Garnier arrived in Hanoi and impetuously counterattacked to retake the citadel with just 50 French soldiers, who were all cut down and beheaded outside the citadel. The Black Flags then pickled the heads of Garnier and the dead French infantry in jars filled with brine to be displayed in Tu Duc’s palace. The remainder of the French troops outside Hanoi then withdrew from the Tonkin. Tu Duc launched a campaign of retaliation against Vietnamese Catholics that slaughtered thousands of believers, as well as killing some European missionaries. In France, there were cries for retribution for the deaths of Garnier’s men and the dead missionaries and Vietnamese Catholics.

French Retaliation

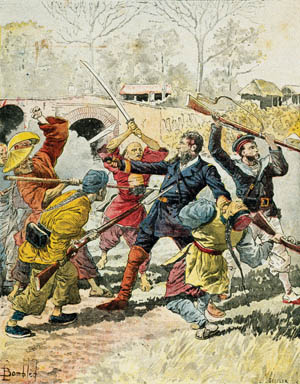

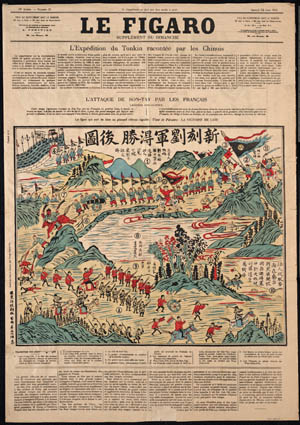

The French army and Foreign Legion were busy quelling Bedouin rebellions in Algiers and other African hot spots and could not respond to these provocations for 10 years. In 1883, a French captain named Henri Riviere was sent with 600 French troops to retake Hanoi and the Tonkin area. Riviere took the city of Hongay and then proceeded toward Hanoi along a hot, dense jungle trail. At Tu Duc’s request, several thousand Black Flag troops had set an ambush in the jungle. Eight-foot-tall elephant grass concealed hundreds of pits filled with sharpened bamboo stakes. The screams of numerous French soldiers whose feet were pierced stopped the column cold. Suddenly, musket fire through the elephant grass dropped over 100 of the unsuspecting French troops. Black Flag troops armed with swords, pikes, and halberds charged. The French gathered into small groups and fought desperately, killing many Black Flag troops before being overwhelmed and cut down to a man. The bodies of the 600 dead French soldiers were all mutilated, and Captain Riviere’s head was mounted on a pole.

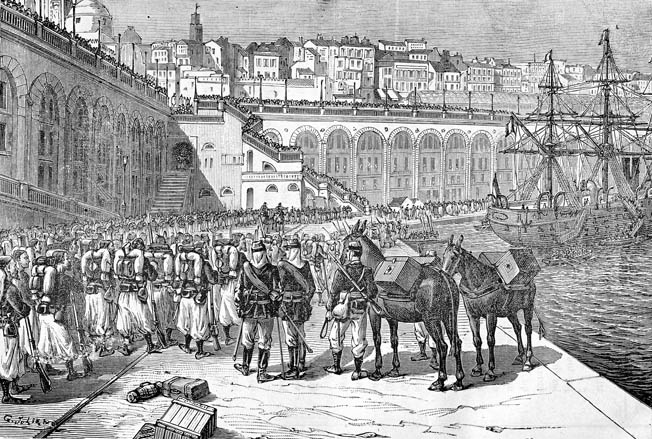

The news of the massacre caused the French parliament to appropriate more than five million francs for a full-scale expedition to impose a protectorate on all of Indochina. On September 27, 1883, a force of 6,000 French Foreign Legionnaires set sail from Algiers for the Far East. Morale was high among the legionnaires, for anything seemed better than the godforsaken deserts of North Africa. Most of the legionnaires had no idea of what they were up against. Nor did they understand that their heavy coats, 90-pound packs, and 10-pound Gras rifles would prove quite cumbersome in the humid, tropical heat of Southeast Asia.

Civil War in Indochina

Earlier in July 1883, Emperor Tu Duc died “with curses of the invader on his lips,” according to a court communiqué. His death caused a multisided civil war that pitted six different mandarins against each other since Tu Duc had no son to ascend the throne. Within a year, three emperors had been enthroned and deposed.

For all practical purposes, the real leader of Vietnam was a warlord named Liu Yung-fu, also known as Liu Vinh-Phoc. He was the leader of the Black Flags, who had virtual control of most of Vietnam. The Vietnamese emperors had to pay protection money to him and get his approval and aide for anything that they chose to do.

Liu was born to an extremely poor family in 1837, in Kwantung province, China, near the Vietnamese frontier. His parents died when he was 16 and he joined the Black Flags. Within a few years, he worked his way into the top leadership position of the gang.

In 1865, Liu and his gang had taken in several thousand defeated insurgents from the Taiping Rebellion and decided to base the Black Flags in northern Vietnam to get away from Chinese government forces in southern China. Tu Duc offered a large sum of money to Lui if he would put down a rebellion by Montagnard tribesmen in northern Vietnam and in Laos.

The Black Flags fought a number of inconclusive battles with the Montagnards but mostly concentrated on building a formidable army from the thousands of Taiping refugees crossing into Vietnam. Eventually, Liu commanded an outlaw army so strong that the Vietnamese emperor feared and respected him.

Demoralizing the Foreign Legion

In August 1883, a French fleet appeared at the mouth of the Perfume River not far from the Vietnamese capital of Hue. A message was sent to Emperor Hiep Hoa demanding the unconditional surrender of Vietnam within 48 hours or “the words Annam and Cochinchina would be erased from history.” Before the Vietnamese could respond, the French warships had bombarded Hue, causing heavy casualties among military and civilian personnel. Emperor Hiep Hoa signed a treaty granting France a protectorate over all of Indochina. Unfortunately for the French, they had asked the wrong people for the treaty. The Black Flags were vigorously preparing for a major war with France.

The French legionnaires disembarked at Haiphong and were allowed to enjoy prostitutes, rice wine, and the beautiful scenery of this area from August to November 1883. The men felt that the war was over and all they had to do was garrison duty and to enjoy the delights of Vietnam. On November 18, the 6,000 legionnaires were sent up the Red River to occupy Hanoi. Everything seemed calm and fine to the French, who did not realize the threat that the Black Flags presented. It was decided to send the legionnaires 35 kilometers through the jungle to destroy the main Black Flag stronghold at Sontay. The French did not know that there was a Black Flag garrison of 25,000 men there, veterans of the bloody Taiping Rebellion.

Day after day, the legionnaires toiled in their heavy backpacks through the swamps and rice paddies—at times waist deep in stinking mud and water and hacking their way through the oppressively humid, mosquito- and leech-infested jungle. Along the way the legion had lost men to wounds from the booby traps. Other legionnaires cursed as they had to carry these wounded men and their gear through the hot jungle. The artillerymen cursed as they dragged their heavy artillery pieces.

During the long nights, legionnaires on guard duty or stragglers mysteriously disappeared. In the mornings, the heads of these men would be found in the camp. After the legion troops had covered more than 20 kilometers of impenetrable jungle, the Black Flags started daily and nightly ambushes that killed several legionnaires at a time. At one point, the legionnaires came upon a grisly site: the heads of Captain Riviere and his ill-fated men pickled in jars of brine. The country had no allure to the unnerved legionnaires. They began to think they were much better off in the desert of North Africa than the jungle of Indochina.

“Vive La Legion! Vive La France.”

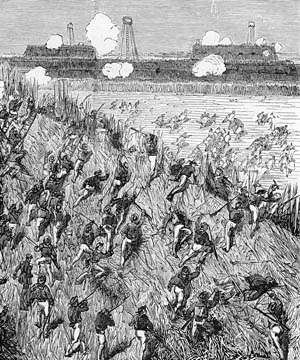

On December 16, 1883, the legionnaires reached Sontay and faced a mighty fortress built in Chinese military fashion. The fortress had a strong citadel in the center with 16-foot high walls on the outside surrounded by a dry, deep moat filled with sharpened spikes. On the outside of the moat was a hedge with thousands more of the dung-covered bamboo spikes. Beyond the bamboo hedge, 400 meters of open rice paddies concealed thousands more of the sharpened bamboo spikes in shallow water.

The French artillery began pounding the fort with little success. The legionnaires fixed bayonets and started wading across the rice paddies. Screams could be heard all across the rice paddies as men discovered that they had bamboo spikes piercing their feet. Yet the legionnaires kept on. All the while, Black Flag artillery and muskets were blazing away. Many more legionnaires cut themselves climbing over the bamboo hedges only to fall into the unseen moat to impale themselves on the bamboo spikes below.

After this journey from hell to reach the walls, the legionnaires discovered that the French artillery had not made a breach in the walls. A runner was sent to tell the artillery to open a breach in the wall as the legionnaires huddled in the moat suffering casualties from Black Flag grenades and friendly artillery fire. A French artillery shell finally struck a pile of Black Flag cannonballs and sacks of gunpowder on the fortress wall, blasting a 20-meter breach. The legionnaires who could still walk charged into Sontay with yells of “Vive la Legion! Vive la France.” Once inside, the legionnaires impaled the Black flag troops on their 19-inch bayonets in retribution for their suffering.

By nightfall, the Black Flag garrison had melted away after suffering 2,000 dead while the legionnaires lost close to 600 casualties. Most of the legion wounded had suffered crippling injuries from the dung-covered bamboo stakes that often led to gangrene infection, amputations, and deaths over the days to come.

The Legion Spread Thin

The legionnaires settled down for a short period of garrison duty at Sontay. In addition to losing many wounded, more men were dying from tropical diseases. In February 1884, another 1,000 legionnaires arrived from Algeria, but they only replaced those who had died thus far in the campaign. In March, the legionnaires were ordered to move east to Bac Ninh, where a garrison of 15,000 Black Flag and Chinese regulars had been sent with orders from Beijing to help stop the French threat.

On March 12, the French column reached Bac Ninh. Once there, it began slashing and burning the surrounding villages and fortified outposts in an effort to isolate the main fortification. French artillery blasted open the front gate of the main fortification to enable a bayonet charge by 600 legionnaires. Once the legionnaires got inside the front gate, they found that they were caught in a killing zone and blocked by a second gate, which was a common feature of Chinese fortifications. The legionnaires retreated to just outside the front gate and sent in 20 sappers, who placed explosives against the second gate. Only five sappers made it back to the front gate before the second gate was blown open. Bloody hand-to-hand fighting took place before the Black Flag and Chinese troops faded away.

During the next few months, the Black Flags were driven from town after town, and French garrisons were left in each one. As a result, the French were spread thinly across the Tonkin and northern Vietnam. Heat exhaustion, malaria, dysentery, cholera, and typhoid were taking a toll and killed hundreds of French Foreign Legion troops. In the meantime, Liu Yung-fu was gathering his scattered Black Flag forces in the north of Tonkin and in southern China as he awaited Chinese reinforcements to go on the offensive to retake the thinly garrisoned towns that he had lost to the French.

Besieged at Tuyen Quang

In November 1884, several thousand Chinese troops arrived with modern rifles instead of the muskets that the Black Flag forces had been using, Nordenfeldt type (Gatling) guns, and Krupp field artillery.

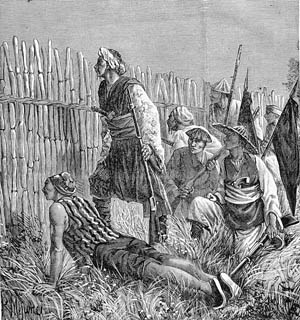

In January 1885, Liu moved south with an army of 20,000 men along the Claire River to Tuyen Quang, which was about 120 kilometers north of Hanoi. The French garrison at Tuyen Quang consisted of 390 legionnaires and 200 Vietnamese colonial troops. The legionnaires garrisoned a captured Chinese fort that was made of bamboo walls that desperately needed repairs from earlier batle damage. The first sign that something was wrong was when the Vietnamese in and around the town began evacuating in panic. Then Black Flag scouts began appearing. The legionnaires, who realized that an attack was imminent, began digging communication trenches between the various points within the fort and to a blockhouse they had built outside.

On January 26, the Black Flag and Chinese forces launched two massive attacks on the outer blockhouse, which would have been overrun had it not been for French artillery support from batteries in the fort. Nevertheless, the blockhouse garrison of 18 men barely held off the attacks with only nine men surviving. After the second attack, the surviving legionnaires retreated along the communication trench to the fort after blowing up the blockhouse with explosives.

Chinese sappers dug tunnels toward the fort, with the idea of mining the walls to breach them for an assault. Early on the morning of February 14, a mine was exploded, causing a corner section of the bamboo wall and tower to collapse and killing 15 legionnaires. Immediately, an assault column of Black Flag and Chinese troops rushed the breach with trumpets blowing, gongs beating, and black flags waving. Most of the attackers were cut down by rifle and artillery fire and from a mitrailleuse (a French Gatling gun). Those few who made it to the breach were impaled on French bayonets.

Over the next few days, more mines were exploded, dividing the wall in two places. Wave after wave of screaming Black Flag and Chinese attackers took staggering casualties from French lead but by sheer numbers forced their way into the fort. Groups of reserve legionnaires counterattacked and drove off the Black Flag and Chinese attackers in desperate hand-to-hand fighting. Day after day, more mines were exploded until there was little left of the fort. The French kept all their troops in the interior of the fort to meet the attackers on top of the debris mounds. The ground was strewn with thousands of bloated, stinking Black Flag and Chinese bodies. The losses did not seem to discourage the attackers, who were willing to take huge casualties to destroy the French garrison. These were tactics that would be repeated against the French and Americans in the 20th century.

“A Moi La Legion!”

The Black Flags and Chinese decided to try a surprise night attack. Quietly moving from their trenches under the moonlight, they overwhelmed the sentries and poured into the fort ruins. The weary legionnaires and colonial troops were roused from deep sleep to the clamor of battle. A bitter hand-to-hand, no-quarter battle was fought in the moonlight, bayonets and rifle butts against swords and pikes until the last of the attackers were killed or had fled.

On February 26, the Chinese detonated six mines that blasted what little was left of the walls and created new lanes through the debris. Dazed legionnaires groped through the smoke, dust, and debris as a hoard of attackers climbed over the rubble from all sides and seemed on the verge of overrunning the garrison when Sgt. Maj. Edmund Hasband yelled from the center of the fort, “A moi la Legion! A moi la Legion! (To me the Legion!)” All the legionnaires and colonial troops ran, walked, hobbled, or were carried to the center of the fort and formed a square of bayonets.

The attackers recoiled from the wall of blade points but continued to climb over their own dead to attack the French square, which could not be broken. At last, after two hours of desperate fighting the grim determination of the legionnaires and their colonial troops won out as the Black Flags and Chinese fell back. They attacked a few more times, but the defenders’ determination to survive won out during the 36-day siege. The stench of decomposing bodies was overwhelming. Finally on March 3, a French relief column received the salute of about 187 exhausted legionnaires and colonial troops (they had taken 403 casualties). French sources say that the Black Flags and Chinese lost more than 4,000 men in the siege.

France’s New Colonies

After this, the dejected Black Flag and Chinese forces retreated to Long Son near the Chinese border. A French column attacked and scattered this force against only token resistance. Liu Yung-fu took the remainder of his forces and retreated to China, where the bandit warlord and his men were treated like heroes for daring to defy France. The French then began bombarding Chinese ports in what became an undeclared war with China. On April 4, 1885, the Chinese imperial government and France signed the Treaty of Tientsin, which recognized a French protectorate over Laos, Cambodia, and the Vietnamese provinces of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina. The region was to be known as French Indochina. The 13-year-old Vietnamese emperor Ham Nghi went into hiding for the remainder of his life as 1,000 French legionnaires sacked Hue in an orgy of looting and killing.

In 1887, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam officially became colonies of France. The French Foreign Legion lost another 2,000 soldiers fighting Vietnamese guerrillas until 1910. To the Vietnamese this was just another long war for national identity. It was a war that would not truly be resolved for many years.

It was Ho Chi Minh who best described the situation that the French and then the Americans got themselves into. He said, “We will be like the elephant and the tiger. When the elephant is strong and rested and near his base we will retreat. If the tiger ever pauses, the elephant will impale him on his mighty tusks. But the tiger will not pause, and the elephant will die of exhaustion and loss of blood.”

What great information USA learned nothing tone deaf

After reading this I wonder if McNamara ever read or was aware of the futility. When I think back to those days it is with horror and the waste of lives.

Some inaccuracies. For the 1873 event, Dupuis wasn’t massacred (he died in 1912) and the Black Flag troops didn’t retake (or even enter) Hanoi. 600 Black Flag troops appeared in front of the city, so Garnier went out of with 18 marines to chase them away but was killed. Nevertheless, the city remained in French hands until a treaty in march 1874.