By David H. Lippman

It was getting dark when they reached Arnhem bridge, but there it was, still intact.

Lieutenant Jack Grayburn’s No. 2 Platoon was led by A Company, and soon they concentrated underneath the ramp carrying the roadway onto the bridge, out of sight of any Germans on the bridge itself. Lieutenant Robin Vlasto later wrote, “Things were organized amid the most awful row. There was a complete absence of any enemy and the general air of peace was quite incredible. The CO arrived and seemed extremely happy, making cracks about everyone’s nerves being jumpy.”

It was 8 pm, the evening of September 17, 1944. After a long march from its drop zone, the 2nd Battalion of Britain’s elite Parachute Regiment had reached the objective of the entire Market-Garden campaign, the Arnhem bridge. Now the battalion—and elements of the 1st Parachute Brigade trickling in—simply had to hold it until they were relieved by the British 2nd Army, heading north from the Dutch-Belgian border. (You can take a deeper look at the fighting in the European Theater and hear its stories straight from the source in WWII History magazine.)

Operation Market-Garden: An “Airborne Carpet”

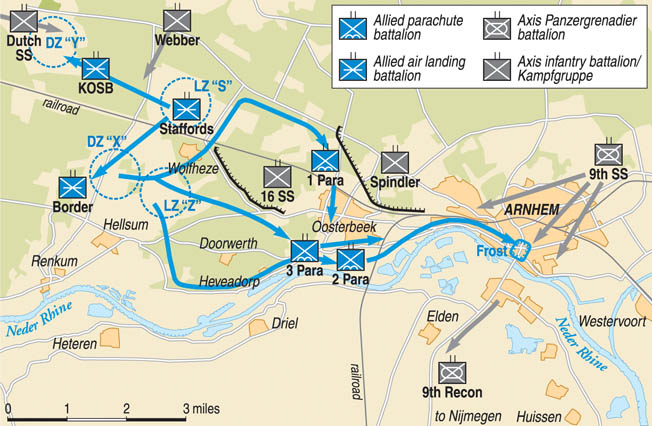

The 2nd Battalion’s arrival at the bridge was the culmination of the Market-Garden plan, which was the largest airborne assault in history. Some 35,000 British and American paratroopers dropped up to 63 miles behind German lines in The Netherlands to open an “airborne carpet” across a series of rivers, enabling the British 2nd Army to drive across the Rhine and be in a position to menace both the Ruhr and the Nazi V-2 sites in Holland. It was a plan that gambled on speed, surprise, and German disorganization, and it was the brainchild of Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery, the victor of El Alamein, not a man known for relying on speed and surprise. But if Monty’s audacious plan worked, it could shorten the war by weeks or months.

In any case, the plan called for the British 1st Airborne Division to make the deepest drop, at the town of Arnhem, 63 miles behind enemy lines. The division’s paratroops and glidermen would land on a field six to eight miles from the Arnhem bridge, the final objective of the Allied drive. Once on the ground, 1st Airborne was to send a squadron of jeeps equipped with Vickers machine guns racing ahead of the ground forces to seize the bridge and hold it until the foot troops marched up.

Assigned to reach the bridge first was the 2nd Battalion, a veteran outfit that had been formed on October 1, 1941. Under the command of the driving Lt. Col. John D. Frost, its men had made combat jumps on a raid into France to seize a radar station and airborne assaults in North Africa and Sicily. The battalion had a strong Irish and Scots character.

Advance Along “Route Lion”

The drop went off almost perfectly, with Frost’s 481 men forming up and heading along “Route Lion,” backed by some Royal Engineers and five 6-pounder (57mm) antitank guns.

The battalion moved through the towns of Heveadorp and Oosterbeek against light opposition, enjoying a rapturous welcome. Captain Tony Frank wrote of his memories of the march to the bridge: “One was [amazed by] the incredible number of orange flowers or handkerchiefs that suddenly appeared like magic. The Dutch were very much in family groups, in staid clothing, out on this fine Sunday afternoon. The second memory was of the problem of trying to stop them slowing down our men by pressing cakes, milk, etc., on them. It was an atmosphere of great jubilation at the start of the move, mainly in the country area near Heveadorp and Oosterbeek, but it petered out when the first hold-up and sporadic firing started. There weren’t so many Dutch out then, but a few stout ones stayed on and watched the fun.”

Private Sidney Elliott remembered, “The Dutch population rushed out of their houses, cheered us, shook hands, gave us drinks, apples and marigolds—and some of us were lucky enough to receive the odd kiss. How could this be war? It was a question that would be answered very soon.”

Ordered not to accept any of the alcoholic drinks offered, the British took the advance more seriously when they came under sniper fire. Soon the battalion reached its first objective, the railway bridge across the Rhine at Oosterbeek. Lieutenant Peter Barry and his men charged the bridge. As they ran up, their hobnailed boots clattering on the bridge’s steel, the center span of the bridge exploded, and metal plates right in front of Barry flew into the air. Barry and his men halted immediately.

“It was lucky that we had stopped when we did, otherwise we would have all been killed,” Barry recalled. “No one was injured in the explosion. Then I felt something hit my left; I looked back and asked if anyone was shooting. They all said, ‘No.’ It was a German bullet. Next I felt a searing shot through my upper right arm, and it seemed to become disconnected; it went round and round in circles; the bone had been completely severed. There were only a few shots, but whoever was firing certainly picked me out as a leader and hit me.”

Barry pulled his men off the bridge, losing one man killed to German rifle fire. Aside from losing a key bridge over the Rhine, Frost’s plan to take the main Arnhem road bridge by passing a company over the rail bridge (thus taking the bridge from both sides at once) was now impossible. He would have to take the bridge at its north end and grab the south side through a coup de main.

Second Battalion moved on … under a railway bridge … through an encounter with a German armored car … and onto the bridge. The battalion’s B Company was embroiled in a four-hour action on the lower slopes of a terrain feature called “Den Brink,” but the rest pushed on, followed by the 1st Parachute Brigade’s headquarters party under Major Tony Hibbert.

Frost’s Headquarters

Now at the bridge, 2nd Battalion’s men moved to consolidate their position. Frost chose as his headquarters a large private house, the upper rooms of which provided a good view of the area. Headquarters and support companies moved into buildings close by, and the vehicles and antitank guns into the sheltered yard of a large office building also nearby.

The Dutch owners of the homes and buildings put up with their new tenants with a mixture of welcome, resilience, and fear, knowing that they soon would be living at the epicenter of a battle.

Second Battalion was soon joined by the Brigade HQ party, which actually initially outnumbered Frost’s force. Brigade HQ was set up in a large office building near Frost’s headquarters.

Assault on Arnhem Bridge

Now for the bridge itself. It was guarded by only 20 or so elderly or very young German troops from a local flak unit, and they were either in a pillbox a quarter of the way across the bridge or asleep in some huts behind the pillbox. They seemed unaware of the British arrival.

The Germans had failed to adequately garrison the bridge because they were more concerned with holding the bridge at Nijmegen. Maj. Gen. Heinz Harmel, who commanded the 10th SS Panzer Division, later lamented that failure, saying that if a few soldiers had been left behind at the Arnhem bridge, it would have been a different story.

Frost sent a group of men under Lance Sergeant Bill Fulton to take the bridge. Fulton said later, “I led off first, up those steps on the west side of the bridge. When I reached the top I heard voices—definitely German. I told the section to be quiet and I peeped over. There was a truck with troops in the back, facing south, only 15 yards or so away. An officer or an NCO was talking to the men in the back. I thought that the element of surprise would be gone if we burst in, so I decided to wait. It was only two or three minutes before the one doing the talking got into the cab, and the truck moved off.

“We started to walk along the right-hand side of the bridge. It was very dark, but you could see outlines. I caught a few of the enemy hiding in corners of what looked like small huts and passed them back to the last man in the section and told him to take them down the steps as prisoners. You could hear firing in other parts of the town, but there was no firing on the bridge itself. Then, in the gloom, I saw a rifle starting to point at me. I swung round to the right and started firing my tommy-gun. I know I hit him because he fired his rifle as he was falling forward and I caught the bullet in the top of my left leg. I told the section behind me to report back and say that the bridge was well-manned and would need more troops. I managed to crawl behind an iron girder, and eventually a couple of medics came for me.”

Fulton spent the next two years in various hospitals.

Major Digby Tatham-Warter, who commanded 2nd Battalion’s A Company, realized a more forceful attack would be needed. He assigned Lieutenant Jack Grayburn to the assault. Grayburn’s men painted their faces black and bound their boots with strips of curtains to make sure there was no rattling equipment or weapons.

Grayburn and his party crept up the side of the embankment and silently began to cross the bridge. They swiftly came under heavy machine-gun fire and had to withdraw, Grayburn wounded in the shoulder, along with seven other men.

For the next effort, at 10 pm, Frost had an antitank gun under Sergeant Ernie Shelswell skillfully backed up by a jeep two-thirds of the way up a path on the side of the approach road embankment and then manhandled to the top to face the bridge. At the same time, a flamethrower team was sent to the house nearest the pillbox, where a gap was made in the wall by firing a PIAT antitank grenade into it.

When all was ready, the 6-pounder fired shots at the pillbox, and Sapper Ginger Williams opened up with his flamethrower. The fire missed the pillbox and instead hit a hut, cooking off an ammunition and fuel store. The explosion set off paintwork on the bridge, and the fire burned all night. The attack was stalled again.

Incredibly, as the night wore on a small convoy of German trucks came onto the bridge from the south. The ammunition aboard the trucks exploded, adding to the inferno and din, and the occupants of the trucks were either killed or bailed out to surrender. The 17 men bagged turned out to be part of a unit that was firing V-2 rockets at England.

740 Men Under Frost

Meanwhile, British reinforcements arrived—part of the 3rd Battalion, the long-delayed B Company of 2nd Battalion, and more engineers. In all, Frost had a decent force: 340 men from his 2nd Battalion, 110 men from 1st Parachute Brigade HQ, 75 men from 1st Parachute Squadron Royal Engineers, 45 men from 3rd Battalion, 17 glider pilots, even a war correspondent. It was an estimated 740 men dug into buildings around the embankment and ramp leading to the north end of the Arnhem bridge—a sizable force, about one and one-half parachute battalions. Frost himself was the senior officer. The 1st Parachute Brigade’s commander, Brigadier Gerald Lathbury, was with 3rd Battalion’s men, who were blocked from advancing to the bridge.

During the night, the Germans did not make any major counterattacks. Both sides waited for the dawn. But the Germans had plenty of powerful forces with which to counterattack. Unknown to or ignored by British intelligence, the 2nd SS Panzer Corps, battered in the Normandy fighting, was refitting and recuperating in the woods and farms around Arnhem and Nijmegen. Despite being understrength, the corps, under Lt. Gen. Willi Bittrich, was a formidable force that fielded a variety of tanks, armored cars, assault guns, and mechanized infantry, all well trained and filled with Nazi elitism.

Swift Reaction From the SS Panzers

The airborne assault had taken the corps by surprise, but as usual the Germans had reacted swiftly, deploying 10th SS Panzer Division’s guns, tanks, and troops to hold the Nijmegen bridge to the south against the American 82nd Airborne and using the smaller 9th SS Panzer Division to surround the British paratroopers at Arnhem and Oosterbeek. Frost did not know it, but his little force was quite cut off from the rest of the 1st Airborne Division.

At dawn, the Germans began to counterattack from the east, probing the British defenses with Mark III and Mark IV tanks, which were easily beaten off. Lieutenant Arvian Llewellyn-Jones described the action:

“The gun spades [on the antitank gun] were not into the pavement edge, nor firm against any strong barrier. The gun was laid, the order to fire given, and when fired ran back 50 yards, injuring two of the crew. There was no visible damage to the tank. It remained hidden in part of the gloom of the underpass of the bridge. The gun was recovered with some difficulty. This time it was firmly wedged. The Battery Office clerk, who had never fired a gun in his life, was sent out to help man the gun. This time the tank under the bridge advanced into full view and looked to be deploying its gun straight at the 6-pounder. We fired first. The aim was true; the tank was hit and it slewed and blocked the road.”

The Germans found the fighting hard, too. Members of the 10th SS Panzer Division’s 21st Panzergrenadier Regiment were sent into the attack, and one section commander, Alfred Ringsdorf, described it as follows: “This was a harder battle than any I had fought in Russia. It was constant, close range, hand-to-hand fighting. The English were everywhere. The streets for the most part were narrow, sometimes not more than 15 feet wide, and we fired at each other from only yards away. We fought to gain inches, cleaning out one room after the other. It was absolute hell!”

“I Suppose They’ll Send a Hearse Next”

The SS attacked again with truck-borne infantry, and Private James Sims, a 19-year-old mortar crewman, saw the Germans bail out of their shot-up vehicles. “One terribly wounded German soldier, shot through both legs, pulled himself hand over hand toward his own lines. We watched his slow and painful progress with horrified fascination, as he was the only creature moving among a carpet of the dead. He pulled himself across the road, and over the pavement, then he dragged his shattered body inch by inch up a grass-covered incline leading to the bridge road. Once he had cleared a slight parapet at the top of the incline he would be back in his own lines. He must have been in terrible pain but he conquered the incline through sheer willpower. With a superhuman effort he heaved himself up to clear the final obstacle. A rifle barked out next to me and I watched in disbelief as the wounded German fell back, shot through the head. To me it was little short of murder, but to my companion, a Welshman, one of our best snipers, the German was a legitimate target. When I protested he looked at me as though I was simple.”

The Germans sent in an ambulance with SS troopers hidden inside. Tumbling out, firing their submachine guns from the hip, their charge was annihilated near Frost’s headquarters. “I suppose they’ll send a hearse next,” a British paratrooper commented. The attacks were piecemeal and uncoordinated, but that would change.

After that, there was a period of relative calm, and Frost called it “a time when I felt everything was going according to plan, with no serious opposition yet and everything under control.”

“Like a Grand Prix Start”

That changed in mid-morning. Between Arnhem and Nijmegen was the 9th SS Panzer Division’s reconnaissance battalion, a tough outfit equipped with 22 armored cars and half-tracked armored personnel carriers. The boss was Captain Viktor Graebner, who had just received the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross the day before, for bravery in Normandy. He had led his unit over the bridge before the British got there, on a sweep down to the main road to Nijmegen. Finding that area clear, he turned back to return over the bridge to reach his divisional command post in Arnhem. He knew the British were on the north end of the bridge, but whether he intended to mount an attack or just dash through the British positions is not known.

Either way, Graebner was no fool, and he prepared for a fight. He was a former Wehrmacht officer who had transferred to the Waffen SS and was described as “an impressive soldier, the right man for the job.” Dark, slightly built, and slim, he was well liked and respected by his men. He had a reputation of always being forward in combat and unafraid to expose himself when necessary in action.

His attack plan depended on blitzkrieg speed and shock, as well as the firepower of his assault guns and armored cars, some of which mounted 75mm guns. All had machine guns. It was the highest concentration of armored vehicles in the 9th SS Panzer Division.

At 9 am, the SS men mounted their vehicles, wearing their “Waffenrock” mottled camouflage uniforms. Surrounded by gray exhaust fumes, the battalion rumbled north up the two-lane road to the bridge. They would dash 600 meters up a ramp and across the 200-meter bridge into the teeth of the British defenses. Armored cars would lead the way, followed by half-tracks jammed with SS troops, roaring along at 20 to 25 miles per hour. Behind them came sandbagged trucks loaded with more infantry to mop up the British defenses.

Graebner, leading the attack as usual, in a captured British Humber armored car, jabbed the air twice, and the column was off, roaring “like a Grand Prix start” according to historian Robert Kershaw.

The Armored Car Attack Meets Heavy Resistance

British lookouts in the tops of the occupied houses drew the officers’ attention to the column of vehicles assembling on the bridge approach.

The armored cars reached the summit of the bridge, cannon and machine guns firing. They maneuvered their way around burning trucks left from the previous actions. The British held their fire, waiting for clear shots. German tracers flew in all directions. Two more armored cars rolled across … then three more—then the British opened up with everything they had, blazing away with Bren and Vickers machine guns, antitank guns, and PIAT antitank weapons.

A leading armored car hit a British mine laid in the road, and its wheel exploded skyward, flying into the air in slow motion, halting the vehicle. British troops hurled grenades into the open half-tracks, which set off a terrible carnage in the confined spaces. Black smoke boiled up in the air as burning fuel snaked across the road. Nearly every German vehicle was hit by PIATs or antitank guns. Sergeant Cyril Robson fired solid-shot shells at the parapet at the side of the bridge until he cut a V-shaped section away and was then able to fire into the sides of German vehicles passing the gap. It is believed that Robson’s gun did more damage than any other weapon.

German troops in the half-tracks found their way blocked and themselves trapped under heavy small-arms fire. One early victim was seen to be flung out on the roadway and literally cut to pieces by a hail of fire. Some vehicles toppled over or slewed off the embankment of the lower ramp, allowing the airborne men in the buildings there to join in the killing.

Everybody seemed to be firing, even Major Freddie Gough, commander of the British jeep reconnaissance squadron, who blazed away with his jeep’s Vickers machine guns. One of his shots killed Captain Graebner. The only officer who was not firing was Frost himself, who watched the battle and said later, “A commander ought not to be firing a weapon in the middle of an action. His best weapon is a pair of binoculars.”

Corporal Geoff Cockayne described the action: “I had a German Schmeisser and had a lot of fun with it. I shot at any Gerry that moved. Several of their vehicles—six or seven —started burning. We didn’t stay in the room we were in but came out to fire, keeping moving, taking cover and firing from different positions. The Germans had got out of their troop carriers—what was left of them—and it became a proper infantry action. I shot off nearly all my ammunition. To start with, I had been letting rip, but then I became more careful; I knew there would be no more. I wasn’t firing at any German in particular, just firing at where I knew they were.”

Two Hours of Battle

Resistance was greater than the Germans anticipated. Vehicles came to a halt when driver and co-driver were killed. Graebner’s attack began to disintegrate. SS Corporal Mauga, crouching in his half-track, witnessed the setback, saying, “Suddenly all hell broke loose ahead of us. All around my vehicle there were explosions and noise and I was right in the middle of this chaos.”

With Graebner dead and the British firing heavily, German morale and cohesion began to break. One driver shoved his half-track into reverse and hit the vehicle behind him. The two were jammed together and became targets for British gunfire. As the vehicles burst into flames, the Germans tried to get out but were massacred by the British.

For two hours the battle raged on. Two German drivers were hit and their vehicles zigzagged out of control, crashing through the left barrier of the bridge and plummeting to the street below “in a shower of cascading burning fuel, wreckage, and screaming men.”

But the SS were determined. Crouching beneath their wrecked vehicles, the troopers struggled to form assault groups and fight their way north. The British used their radios to call in artillery fire from the distant 1st Airborne Division, and shells looped into the German wreckage, adding to the carnage and din.

As noon approached, the Germans realized the situation was hopeless and began to withdraw on foot. Some leaped from the bridge into the Rhine River, unable to pass through blazing vehicles. As the Germans withdrew, the sound of gunfire was replaced by the wailing of a jammed horn on one of the 12 knocked-out vehicles on the bridge, and the sound of British paratroopers shouting their war cry, “Whoa Mohammed,” which added insult to the German injury. The British lost just 19 men.

The German’s Shift in Strategy

Graebner’s defeat had a huge impact on the 9th SS Panzer Division. They realized the British paratroopers would be tougher customers than the enemies they usually fought and often defeated. It would be suicide to attack across the bridge again, 9th SS Panzer Division commander Colonel Walther Harzer decided, and he would shift his momentum to the north side of the bridge to dig the British out.

The Germans were not done yet. Their next attack was against the eastern side of the perimeter held by Lieutenant Pat Barnett’s Brigade HQ Defense Platoon. Preceded by artillery and mortar bombardment, the Germans sent in two tanks and infantry under the bridge ramp. The British knocked out the tanks and drove the infantry back.

The rest of the day saw further minor attacks and mortar and artillery shelling of the British positions. Both sides realized it would be a long siege. The British needed the bridge—it was the whole point of the operation—and the Germans needed it as well, to move troops and supplies to the defense at Nijmegen.

That evening, Frost got word that his brigade commander, Gerald Lathbury, was missing. Tony Hibbert asked Frost to take over all the brigade’s elements at the Arnhem bridge. Major Digby Tatham-Warter, who walked around the battlefield displaying a rolled up umbrella, took over the battalion.

First Night at the Bridge

The airborne men dug in for their first full night at the bridge. The houses on the western side of the perimeter had hardly been attacked, so part of B Company was redeployed to the eastern sector. A house near the bridge was deliberately set afire to provide illumination for the bridge area, and B Company was ordered to send out a standing patrol to ensure that no Germans tried to cross the bridge. Royal Engineers examined the underside of the structure to be sure the Germans could not demolish it.

At 3 am on the 19th, a German force apparently got lost and stood by the school building manned by 3rd Battalion’s men, talking nonchalantly. The British reacted at once. Lieutenant Len Wright described the action as follows:

“We all stood by with grenades—we had plenty of those—and with all our weapons. Then Major Lewis shouted, ‘Fire,’ and the men in all the rooms facing that side threw grenades and opened fire on the Germans. My clearest memory was of ‘Pongo’ Lewis running from one room to another, dropping grenades and saying to me that he hadn’t enjoyed himself so much since the last time he had gone hunting. It lasted about a quarter of an hour. There was nothing the Germans could do except die or disappear. When it got light there were a lot of bodies down there—18 or 20 or perhaps more. Some were still moving; one was severely wounded, a bad stomach wound with his guts visible, probably by a grenade. Some of our men tried to get him in, showing a Red Cross symbol, but they were shot at and came back in, without being hit but unable to help the Germans.”

No Sign of Reinforcements

The British were holding on. But there was no help at hand. The 9th SS Panzer Division and other German units had done an effective job of blocking the rest of the 1st Airborne Division from marching to 1st Parachute Brigade’s relief. Nor was there any sign of the tanks of XXX Corps, the vanguard of the ground element of Operation Market-Garden. As Tuesday dawned over a smoky and battered Arnhem, the British paratroopers at the bridge knew they had held out the two days required. Where was the relief force?

The Polish Parachute Brigade was supposed to parachute in that very day, dropping on the south side of the Arnhem bridge. Frost readied a Bren carrier and two reconnaissance jeeps to meet the Poles, but they did not appear. Their lift was postponed by fog in England.

Instead, the morning was relatively quiet, punctuated by artillery, mortar fire, sniping, and infiltration. The Germans were concentrating on stalling the British efforts to relieve 1st Parachute Brigade on the bridge rather than on the bridge itself.

But by noon, three German tanks drove into the bridge perimeter from the east, close to A Company’s positions on that side of the ramp. Their shelling of one of the A Company positions forced the British to evacuate the house. Captain Tony Frank and a soldier operated a PIAT and hit a German tank. “I hit it first time, right in the backside,” Frank said later. “It didn’t burn, but it didn’t move again.”

Sending an Emissary to the British

During the morning, the Germans requested a truce to ask the British to consider surrender. To the orderly Teutonic mind, the British were in a hopeless position with no chance of relief. The emissary from the Germans was Lance Sergeant Stan Halliwell of the First Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers, who had been captured earlier that morning while on a sortie taking ammunition to an exposed party of his unit. He described the incident as follows:

“They took me to a building where they seemed to have an Operations Room. An officer who seemed to be a big noise called me over. He inspected my pay-book; then he said, ‘There is going to be a truce and I want to send you with a message. We trust you to be a gentleman and return.’ I told him I would. The message was for Colonel Frost—he knew his name—and I was to ask him to be under the bridge at 10:30 am to discuss a surrender.

“I was taken outside and lined up with some Germans to approach our lines. But our lot were firing—there was no truce—and the Germans opened up too. I ran across, shouting at our chaps not to shoot me. Then I went to find Colonel Frost, running from building to building in all the firing and the smoke; that was the worst 10 minutes of my life. Colonel Frost told me to tell them to go to hell, but I wasn’t going to go back just to tell them that and I stayed with our troops.”

Under German Shellfire

The “big noise” was Maj. Gen. Heinz Harmel, boss of the 10th SS Panzer Division, and his zone of operations included the bridge and main road down to Nijmegen. He was ordered to open the road as quickly as possible. He spoke fluent English, having toured England with his school football team before the war.

After realizing that the British would not surrender, the Germans started exerting more pressure. Rather than mount costly infantry attacks, the Germans decided to destroy the British positions by artillery and tank shelling, using phosphorous shells to set the buildings alight. The methodical bombardment began and would continue until the end of the battle, gradually wearing down the British ability to resist.

Building after building was hit by German shells. Corporal Horace Goodrich, at Brigade HQ, described a typical incident: “The enemy brought up a self-propelled gun to shell our building, and I happened to be manning a Bren gun in the right place to engage it and the infantry who were standing round it. After getting off two short bursts, I observed what had all the appearance of a golden tennis ball at the mouth of the SP gun. The next moment I was lying on my back covered in dust and debris. The shell actually struck the wall at my feet. Having got the range, they were able to fire at will until the top floor became temporarily untenable.”

That evening, the Germans rolled in massive Tiger tanks, which packed 88mm guns and immensely heavy armor. They crunched along the street between the Van Limburg Stirum School and the nearby houses, shelling each house, spraying the area with machine-gun fire. The British brought up their 6-pounder antitank guns, but they were unsuccessful in stopping the massive Tigers.

Private Kevin Heaney of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) described one such shelling: “A shell came whooshing through the open bedroom window and hit the back of the house. The back wall became a pile of rubble, and the floor fell in. One of the signalers, resting on a bed in the back bedroom, came down with the floor and was trapped. He could not move, as his back was broken. Sgt. Mick Walker, one of our men, climbed down to give him a morphine injection. My pack was in the back bedroom and I was disappointed when this was lost; I had not touched the rations inside. We then took shelter in the cellar and started hoping for the best. There was a noise at the top of the stairs, and someone started to wave a white handkerchief, but Mick Walker knocked this out of his hand. It was probably only more rubble falling down.”

The men evacuated the house and went to another nearby, but this also had to be given up. As the shelling continued, the British evacuated more houses.

The shelling did not cause more fatalities, but men were wounded. Among them Father Egan, 2nd Battalion’s Catholic padre; Major Tatham-Warter (twice); and Captain Tony Frank, putting Lieutenant Grayburn in charge of what was left of A Company. Lieutenant Harry Whittaker was hit while driving a jeep hauling one of the 6-pounders—he died the next day.

The Paratroopers’ Desperate Situation

The British hung on with grim determination, but their ability to do so was beginning to slacken. They had lost three officers and 16 men in the last 24 hours and suffered between 100 and 150 wounded. The medical team was short of supplies. Food and ammunition were also running desperately low.

Signalman George Lawson was sent to obtain more ammunition and double-timed through the smoke and gunfire to Battalion HQ. There he found Major Tatham-Warter. “He was the coolest chap I ever saw, walking about with his red beret, one arm in a sling, with his umbrella hooked over it and his right hand holding a revolver, directing operations,” Lawson said. “He asked me what I wanted and, when I told him, he said, ‘Hurry up and get some and get back to your post, soldier; there are snipers about.’”

Other Britons relied on their sense of humor to cope with the situation. Signalman Harold Riley described such an incident: “We were all feeling pretty grim, when suddenly a 2nd Battalion chap who had been crouching in a corner crawled on his hands and knees towards a desk in the middle of the room. He reached up and gingerly plucked a rather battered telephone receiver from it. Speaking into it he said, ‘Hello, operator. Give me Whitehall 1212,’ a pause, then, ‘Mr. Churchill? There are some men outside annoying us.’ Maybe it sounds a little corny now, but at the time it did relieve the tension somewhat.”

As dusk fell, many houses were burning. Sapper Tom Carpenter described the area around the bridge as “becoming a sea of flame. The roar and crackle of flaming buildings and dancing shadows cast by the flames was like looking into Dante’s inferno.” Two of the nearby church towers were on fire, and one of their bells swung in the wind, clanging irregularly. Frost wondered why his men had yet to be relieved, either by the 1st Airborne from the west or XXX Corps from the south.

The night passed quietly, and dawn arrived with a dull and damp drizzle. The British were still holding 10 of their original 18 houses in the perimeter, but it was split into two parts divided by the ramp. The Germans allowed stretcher bearers to pass through in the open, but all other movement was extremely dangerous.

Now there was no thought of tactics or strategy. Frost’s only effort was to hold all positions until each building was destroyed. The Germans were shelling the British positions from all sides, with tanks crunching into the perimeter. The defenders needed help.

None was forthcoming. The 1st Airborne Division was now in a small, thumb-shaped pocket in Oosterbeek, based on the Rhine River, barely able to hold on against German attacks, short on supplies. Relief from the south depended on the American 82nd Airborne finally taking the Nijmegen bridge, but all efforts to do so had failed so far.

By now the British defenders were exhausted from lack of sleep and food. Roving German tanks and artillery hammered the British. When exhausted British troops from the Brigade Defense Platoon heard tanks clanking nearby, they thought it was XXX Corps at last and rushed to the windows to greet their liberators. It was actually a pair of German tanks, and they shelled the British position, wounding a lone American defender, communications officer Lieutenant Harvey Todd, who fired at the Germans with his Springfield automatic carbine.

Next to get blasted was the Royal Army Service Corps platoon, holding a house hard by the Arnhem prison wall. The Germans blew a hole in the wall to enable them to shell the British. Driver Jim Wild described it: “The first shot hit the corner of the roof. It didn’t explode there because the only resistance it had was the slates on the roof, but it left a hole nearly two yards across. The lads underneath it were showered with debris; I wouldn’t like to repeat what they said. The shell exploded against the brickwork at the other end of the long room. We were all down on the floor. A lot of shrapnel was flying about, and I think one man was killed and one wounded. We decided to get out, down to the ground floor, when the second shell exploded against the front wall of the room we had been in; we would all have been killed if we had still been there.”

The two antitank guns were still in action, but the German infantry were now in positions from where they could fire directly down on anyone who attempted to man a gun. The 2nd Battalion’s 3-inch mortars were the only weapons capable of hitting back at the German artillery.

But the Germans still made mistakes that enabled the tough paratroopers to score some victories. Private Sidney Elliott of B Company described one incident when a half-track halted outside his house near the riverside: “We heard the rattle and clanking of a vehicle and, on looking out of the window, we saw a half-track with, I think, four Germans aboard. We were by now extremely short of ammo, but we had one Gammon bomb left. This was immediately primed; one of us tossed it and it landed in the half-track. I can still see one of the bodies as it seemed to rise into the air and disappear into the river.”

Lieutenant Grayburn’s Victoria Cross

The Germans now launched a series of infantry attacks with close tank support from the east, hoping to reach the area underneath the ramp. The last defense in front of this area was a group of houses held by Brigade HQ men, signalers, and RAOC. Private Kevin Heaney, an RAOC man, described the scene:

“The atmosphere and tension grew unbearable. We were expecting to be attacked but uncertain from which direction this was going to come. The mood varied between hope and despair, and the lack of news from the rest of the division or progress by 30 Corps was bad for morale. A young officer, a studious looking chap, gave us a pep talk, trying to be a morale booster, saying how well our brigade had done in North Africa and how our performance at Arnhem would go down in history. But I had not been in North Africa and the thought went through my mind, about fighting to the end, ‘not if I can help it,’ particularly as there was talk of leaving the wounded behind.”

The German intention was apparently to seize the small archway over the road and blow that, denying the Arnhem bridge to the advancing British armor to the south, without blowing the massive structure itself. The Germans stormed in and attempted to place explosive charges against the pillars while British engineers counterattacked to stop them.

Lieutenant Jack Grayburn and some of his A Company men accompanied a party of Royal Engineers, which dashed out and removed fuses from the charges around the piers. It was “a nerve-wracking experience,” according to Engineer Lieutenant Donald Hindley, “working a few feet away from a large quantity of explosives which could be fired at any moment.” Grayburn was wounded but returned after being treated, one arm in a sling and with a bandaged head.

Hindley recalled, “It was obvious that the enemy would quickly restore the fuses, and a second, heavier attack was made to try to remove the charges themselves. However, the enemy had by now moved up a tank to cover the work. We were quickly mown down. Lieutenant Grayburn was killed—riddled with machine-gun fire. I escaped with flesh wounds in my shoulder and face.”

Grayburn earned the only Victoria Cross awarded at the Arnhem bridge battle. His body fell into the Rhine River but was recovered in 1948 and buried in the Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery. His Victoria Cross is at the Parachute Regiment’s headquarters in Aldershot.

Frost Wounded

At 1:30 pm, Lt. Col. Frost was crouched on top of a pile of rubble talking with Major Crawley when a mortar bomb went off and wounded both officers in the legs. Frost was finally out of the battle, and Major Hibbert appointed Major Freddie Gough of the Reconnaissance Squadron to command what was left of the brigade. Frost agreed to the move, saying:

“I was taken to the aid post. I was quite affected by the blast as well as being wounded and I really wasn’t able to control things. Freddie came along, and I told him to carry on—not that there were any orders much to give by then. That was the very worst time, the most miserable time of my life. It is a pretty desperate thing to see your battalion gradually carved to bits around you. We were always hoping, right to the bitter end, that the ground forces would arrive. As long as we were still in place around the bridge, preventing the Germans from bringing up anti-tank guns to engage the 30 Corps tanks, we were doing our job. But it was only isolated groups by then, with no proper control over the area.”

“Time to Put Up the White Flag”

At the same time Frost was wounded, the British lost one of their most important positions, the Van Liburg Stirum School building, halfway along the eastern side of the ramp embankment. The Royal Engineers and 3rd Battalion men had held this site with little heavier firepower than their rifles and a Bren gun but were now overwhelmed. They were out of food and water, low on ammunition, and had only 30 men unwounded. The Germans systematically began shelling the building, blasting off its roof and top story. One shell set the roof ablaze, and another burst where two officers, Major Pongo Lewis and Lieutenant Wright, were taking their turn to rest. Wright was so stunned that he had no memory of the next few hours.

What happened next was a subject of contentious accounts, but the building was no longer tenable. The intention was to evacuate, but supposedly Major Lewis called up from his mattress, “Time to put up the white flag.” The second in command, Captain Chippy Robinson, asked if the fit men could at least break out. Lewis said, “Every man for himself,” and Robinson and Captain Eric Mackay dashed across the road into the gardens of some houses to the east. Unfortunately, they were taken prisoner, but Mackay eventually escaped and reached England.

While some of the engineers bailed out to fight again, the wounded could not leave. Some engineers did not like the thought of abandoning the wounded and stayed behind. Major Lewis sent a sapper to the top of the embankment with a white towel tied to his rifle, but he was immediately struck in both legs by a burst of machine-gun fire. He died of those wounds five months later. The Germans cautiously moved in on the defenseless school and found the wounded men and their caretakers awaiting capture.

A German officer inspected the wounded, found one of them hopeless, and shot him in the head with a pistol.

“How About Packing it in?”

At the southern part of the perimeter, a considerable body of men had gathered among the pillars under the ramp archway nearest the river. These men had been burned out of their houses and were sheltering where they could. The ubiquitous Major Tatham-Warter turned up and ordered them to move to Brigade HQ’s position, a 180-yard dash across fire-swept ground.

Sergeant George Lawson recalled, “I heard the shout, ‘Every man for himself.’ A group of us made a dash for it. We had to go through a mortar barrage first; that’s where young Waterston got hit. He was leaning against this wall. I thought I should go back for him, but he was turning blue, and I carried on. Several of the others were hit, too; I was hit in the face by shrapnel. I now slung my rifle away because the bloody thing was useless; it wasn’t working properly. I took the bolt out and threw it away. A group of us then tried to cross the open road, but four or five of us were mown down by machine-gun fire. I turned back and took refuge in one of the burnt-out buildings—how long for, I don’t know, but I was forced to get up because my gas cape and my smock were burning from the hot stone.”

Now the defense was starting to disintegrate. Private Kevin Heaney and six men were trapped in a hallway, the Germans 50 yards away. “How about packing it in?” Heaney asked his colleagues, including a wounded man. “One chap said, ‘I’m easy;’ I don’t think he was ready to surrender, though. I put my hand inside my jacket, tore off my vest, gave it to the man nearest the opening, and he waved what was, in effect, the white flag,” Heaney said. The Germans shouted for the British to come out. When they did, the Germans opened up with machine-gun fire, hitting the first four Britons.

“I assumed the Germans who fired were themselves under fire from our men. That was my charitable interpretation as to why they fired, because they were very chivalrous generally,” Heaney said. He and the wounded men got back into the house and sat in the rubble, listening uneasily to mortar fire. “We were there for about two hours. I had my prayer book open and was saying the Prayers for the Dying. Later on, the Germans came in, rescuing the trapped men and taking them prisoner, and this great big German came and took the two of us also.”

Demolishing the British Defenses

The defense was now squeezed into an area one-fifth of its original position, holding 10 of their original 18 buildings. The British troops were exhausted—with no food and little water, and most were still going on Benzedrine tablets. Two German battle groups, backed by rocket artillery and Tiger tanks, further pressured the British.

The Germans methodically demolished the British defenses, using a pair of Tiger tanks that managed to nose their way through the wreckage of Graebner’s vehicles across the Arnhem bridge. Two further 88mm flak guns were set up on either side of the southern approach to the bridge, delivering point-blank fire. SS Section Commander Alfred Ringsdorf declared the only way the British were going to get out was to be carried out “feet first.”

SS Grenadier Private Horst Weber recalled the heavy artillery barrage: “Starting from the rooftops, buildings collapsed like dolls’ houses. I did not see how anyone could live through the inferno. I felt truly sorry for the British.”

Another SS man, Rudolf Trapp, watched artillery firing point blank down the Eusebius-Plein: “An artillery piece was trundled into our street from the Battalion Knaust behind us. This was two or three days after the battle started. It was the biggest gun I’ve ever seen, and was manhandled up along the side of the Rhine.” The big problem with the gun was getting it into action while under fire.

Trapp said, “I covered it by shooting up the British positions along the street with long protracted bursts from my machine gun.” The Knaust gun crew was with the first Wehrmacht troops to enter the Arnhem battle. It opened fire on Major Crawley’s position, reducing a strongpoint to rubble with seven or eight shots. After the barrage, Trapp’s men stormed the position and found the occupants all dead, lying in slit trenches and prepared positions.

“A Nightmare of Buildings Reduced to Rubble”

Battle Group Knaust was commanded by Colonel Hans Peter Knaust, a one-legged Eastern Front veteran, and this powerful group fielded Panther and Tiger tanks. Two of them clanked into action near Weber, who saw them hurling shells into each house at close range. Weber recalled a corner building “where the roof fell in, the top two stories began to crumble and then, like the skin peeling off a skeleton, the whole front wall fell into the street revealing each floor on which the British were scrambling like mad. Dust and debris soon made it impossible to see anything more. The din was awful, but even so above it all, we could hear the wounded screaming.”

The arrival of Knaust’s tanks tipped the battle for good. Frost’s men, immobilized by the superior weight of infantry around them, were being systematically pummeled into submission by the heavy guns.

One of Knaust’s men, Lance Corporal Karl-Heinz Kracht, was a loader on a Mark III tank. His machine rolled past the wrecks of Graebner’s vehicles. “Personally, I felt quite a bit of apprehension as our vehicles moved into Arnhem. I still had to overcome the shock at the destruction and the corpses lying by the roadside. Maybe we were to be the next victim of the British antitank guns? This feeling was amplified when the company lost its first tanks,” he said.

Kracht and his tanks supported SS infantry winkling out British paratroopers. By now the exhausted Britons were beginning to surrender.

Kracht pulled out his Agfa Karat III camera and began to take snaps of the periphery of the action around him, catching panzergrenadiers going into action and buildings being wrecked.

“As far as we were concerned, this shooting lasted for two days until nothing more stirred on the bridge,” Kracht said later. “Panzergrenadiers, also suffering most of the casualties, had to do the dirty work again. Even so we lost another tank. All around the bridgehead was a nightmare of buildings reduced to rubble, shot-up vehicles and guns, and corpses—of friend and foe alike.”

Rudolf Trapp’s Doomed Half-Track

In such close fighting, collecting the wounded was becoming a problem. SS machine-gunner Rudolf Trapp, being 19 and agile, was assigned to do so. “We were told to get some wounded or dead SS men out of the enemy field of fire,” he said. “To achieve this we got an armored half-track. Putting down covering fire with two machine guns on it, we would race down the street, open the rear door, pull our mates in, and fire away as we sped back to cover. All the time we would hope there would not be a stoppage on the machine gun because the British fired very accurately. In one case they shot a man in the heart straight through his military record book.”

The British fought on with the courage of despair. Trapp was ordered to use his half-track to crawl through the rubble and make contact with troops coming in from the east. The route they would have to take was dominated by a British anti-tank gun. Trapp recalled, “Bernd Schultze-Bernd was our driver, a farmer’s son from Sendenhorst in Muensterland. He was one of the three old company veterans. There were tears in his eyes. He told our company commander that this was not going to work. But an order is an order. To be on the safe side, the two of us stuffed the pockets of our smocks with hand grenades and ammunition for the .008 pistols. We raced past the crossroads and got hit on the left, near Bernd’s driver’s seat. The vehicle came to a halt. Bernd was dead, a direct hit from the shell.”

Trapp and his surviving pals bailed out of their half-track and took shelter in a ruined cellar. As the British closed in on them, they grenaded their way out and made their way to the river bank. There they abandoned their uniforms and swam through the murky water between moored boats, under rifle fire, until they reached their own men.

Once back with their buddies, Trapp and his crew had their wounds dressed, were issued uniforms from their dead comrades, and rejoined the fighting.

A Two-Hour Truce

That afternoon, German tanks and troop convoys began using the Arnhem bridge again. At the same time, the 82nd Airborne made its legendary river crossing to take the Nijmegen bridge. It was 6:30 pm before the first tanks of Sergeant Peter Robinson’s troop from the Grenadier Guards rolled across the bridge. But the tanks needed to replenish ammunition and fuel after earlier hard fighting in Nijmegen, and the infantry battalion with which it normally worked was still tied up fighting in Nijmegen as well. There would be no XXX Corps drive north that evening. The defenders at Arnhem bridge were on their own.

At the bridge, Brigade HQ was on fire and many buildings were full of wounded men. The two doctors told Frost that evacuation of the wounded would require a truce, so some of the German prisoners were sent out with white flags to arrange this. It was quickly agreed, and the fighting stopped for nearly two hours.

During the truce, Gough conferred with Frost on what to do next. Frost was wounded and in a cellar, waking up from the morphine he had taken. “I told [Gough] to move. I gave him my own belt with revolver and compass and we wished each other luck. Down below where I lay it was pitch black and we had to use our torches continuously.”

Major Gough sent the able-bodied men from the building northward into the town. Corporal Dennis Freebury was one of them, and he recalled:

“Major Gough, with his arm in a sling, and his silver hair, in shirt sleeves—a swashbuckling character—gave us a pep talk. It was a bit like Hollywood. He said, ‘I want you to go out, do your best and see if you can get back to our own forces—and just remember that you belong in the finest division in the British Army.’ Nobody cheered or anything like that, but it made one feel good.”

Gough did not join these men but stayed with the 2nd Battalion in their positions; the medical officers and their orderlies became prisoners. The 280 wounded, including some German prisoners, were taken with Dutch civilians who had been sheltering in the building, and most of the wounded eventually reached St. Eizabeth Hospital.

It was now after nightfall, but the blazing buildings made the scene as light as day. A German officer wandered around the 2nd Battalion’s slit trenches handing out cigarettes and telling the Britons they did not stand a chance and should surrender. The British answered him with rude remarks.

The Germans took advantage of the two-hour truce to advance their positions, and Major Tatham-Warter sent Captain Hoyer-Millar, who spoke some German, to protest. Hoyer-Millar recalled: “I found an officer in a long dark leather coat. He spoke good English. I warned him that if his men continued, we might have to open fire. He, in turn, kept stressing that there was no hope for us and that we should surrender. I told him there was no chance of that and that we were confident our ground forces would soon be up to relieve us. I think I must have introduced myself, or they got my name from someone else, because when the action continued several hours later I heard a rather uncanny, wheedling voice calling ‘Captain Millar’ or ‘Captain Muller’—just my name —quite pointless, because I made no reply.”

“Out of Ammunition. God Save the King.”

The end was nearly at hand. The 120 men of Brigade HQ group reached the meeting point at the convent school. Major Hibbert recalled, “We decided that, as we could no longer see the bridge and had virtually no ammunition, we could be of most use if we got back to the divisional perimeter and got more ammunition. So we split up into sections of 10 men, each under the command of an officer, to try to slip through the enemy lines.”

Meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion men went on fighting. Captain Hoyer-Millar and his exhausted men were practically out of ammunition but dug deep into their slit trenches to wait out the shelling, hoping to at least disrupt incoming infantry attacks.

“There was undoubtedly bitterness and skepticism about the performance of Monty’s ground forces,” Hoyer-Millar later said. “But those of us who had taken part in the Primosole bridge operation in Sicily recalled that, 24 hours overdue, the first troop of Eighth Army tanks had finally reached us when we were hanging on by our fingernails; might it not happen again? I recall clearly how, during those final hours, one line of A.H. Clough’s famous poem kept springing to mind: ‘If hopes were dupes, fears may be liars’ … but deep down there was the feeling, ‘They’ve just written us off.’”

Major Tatham-Warter, limping, still clutching his umbrella, decided that the remaining men should split into two parties, one under himself, the other under Major Francis Tate, the HQ Company commander, and hide for the night before reoccupying the positions the next morning. But the Germans were now all over the area, so the plan was scuppered. More scattered fighting took place, and Major Tate was killed. The remaining Britons tried to escape, but it was hopeless. Out of ammunition, they became prisoners.

One group of British engineers fired off a last radio signal to division headquarters, which astonished the Germans who intercepted it: “Out of ammunition. God Save the King.”

Lieutenant Tony Ainslie recalled his party being trapped in a house, with Germans outside calling on them to surrender.

“Some of my group had already been hit, so I yelled back in German, ‘Don’t shoot. There are wounded here.’ And we walked across the street into captivity,” he said. “The first person in authority we saw was an NCO. He was slightly cross-eyed, his tunic was open, and he was wearing a blue-and-white striped civilian shirt underneath. He said, ‘Good evening. That was a lovely battle, a really lovely battle. Have a cigar. We are human too.’ So, after doing what we could for the wounded, we all sat down, smoking foot-long cigars, and had a matey chat about the events of the past few days.”

They might have had a lot to talk about. The British paratroopers standing at Arnhem bridge had fought to the limits of their resistance. Of the men who started the fight, an estimated 10 officers and 71 men were killed or would die of their wounds—11 percent of the defenders. The use of the bridge had been denied to the Germans for three critical days, and a large portion of the 10th SS Panzer Division had been tied down and suffered heavy casualties. The 1st Brigade’s sacrifice enabled both the rest of 1st Airborne Division to hang on in its Oosterbeek perimeter and the 82nd Airborne to take the Nijmegen bridge, allowing the British to finally hook up with the 1st Airborne Division and evacuate the survivors.

Britain’s Alamo

In the end, it was a defeat for the British, but it was one of the valiant stands that they loved so well—an outnumbered and outgunned force hanging on against overwhelming odds, refusing to surrender. The 2nd Parachute Battalion and its cohorts never actually surrendered as an organized body. Its men were winkled out of their buildings in small groups, still defiant. It was very much Britain’s Alamo.

John Frost was also down in a cellar when the Germans overran his area. “Both sides labored together to get the wounded out and I saw the Germans were driving off in our jeeps full of bandaged men,” Frost recalled. “The SS men were very polite, but the bitterness I felt was unassuaged. No living enemy had beaten us. The battalion was unbeaten yet, but they could not have much chance with no ammunition, no rest, and with no positions from which to fight. No body of men could have fought more courageously and tenaciously than the officers and men of the 1st Parachute Brigade at Arnhem bridge.”

I AM SURPRISED THAT RAF AND AMERICAN AVIATION DID NOT SUPPORT FORCEFULLY THE FORCES ON THE GROUND, AS THE LUFTWAFFE DID SUPPORT IN 1941 THE GERMAN PARACHUTED IN CRETE !

Giacomo, thank you for your comment on my article.

British 1st Airborne lacked a communications unit to connect with the RAF’s 2nd Tactical Air Force, which prevented them from supporting the Red Devils. That was one of the many mistakes made in planning an operation of this size in one week.

Field Marshal’ Montgomery’s real mistake was to fail to get “hands-on” in the operation’s execution. In Market-Garden, he put up with behaviors and decisions by his junior officers that he would not tolerate in Egypt, Tunisia, Sicily, and Italy. That failure was disastrous.