By Glenn Barnett

Most Americans were surprised by the Japanese attack on pearl Harbor, but the military had known that war with Japan was inevitable. During the summer and fall of 1941, a belated effort had been made to reinforce far-flung U.S. bases in the western Pacific.

In the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur was calling for every type of aid. At the top of his list were Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers and the crews to fly them. In November 1941, the 27th Bombardment Group was dispatched to Manila. With them was flyboy Damon “Rocky” Gause. When Gause landed in the Philippines he could not imagine the adventure that lay ahead of him. For the next 11 months he was in constant danger of capture and death from a ruthless Japanese enemy.

“Am Alive and Giving Them Hell”

Damon was born in Jefferson, Georgia, population 2,000. Schoolrooms were boring for the restless young man who craved adventure. He served a stretch in the U.S. Coast Guard and then the U.S. Army in Panama. He worked as a roustabout on oil rigs in South America and took up amateur boxing. Time spent in the local jungles would soon serve him well. His adventurous nature led him to take up flying, and he soon earned his wings.

Flying was expensive, but there was an inexpensive way to log flight hours. Once again Gause enlisted in the Army. He was commissioned as a lieutenant and assigned as a communications officer to the 27th. The bomber squadron steamed into Manila Bay on November 27, 1941. The personnel landed without supplies, equipment, or airplanes. For the next 11 days Lieutenant Gause and his mates unloaded ships by day and partied the nights away.

On Monday morning, December 8, that all changed. Across the time zones it was Sunday morning in Hawaii. Radio monitors in Manila picked up the famous “This is no drill!” message at 3 am. At Fort McKinley at 8 am when the men arose for breakfast, a loudspeaker made them aware of the air raid on Pearl Harbor and blared orders to report for duty.

Lieutenant Gause and his men were ordered to set up a communications post, but their radio equipment was still on the docks or aboard ship waiting to be unloaded. Through diligent efforts the men of the 27th were soon rounded up, along with supplies and radio equipment. Within three hours a communications center was up and was transmitting to Hawaii in the east and China to the northwest.

No sooner were communications secured than the first wave of Japanese planes arrived overhead to begin a relentless bombing campaign. After that first raid, Gause sent a radio message to his wife, “Am alive and giving them hell—Rocky.”

Gause’s Escape From Captivity

Unlike the single attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese returned again and again to pulverize Philippine and American air, naval, and army forces. Without airplanes, the flyboys of the 27th became riflemen.

On December 22, up to 43,000 Japanese troops landed on northern Luzon. More troops would follow. Gause and his communications command were eventually ordered to the Bataan Peninsula with the surviving defenders.

While the American and Filipino troops set up their new defensive lines on the peninsula, Rocky and a few intrepid friends drove into Manila and daringly braved the oncoming enemy to gather food and supplies and to continue the waning party life in the capital. A young Filipino woman named Rita Garcia invited Rocky and a buddy to a New Year’s Eve party at the Manila Hotel, recently the headquarters of General MacArthur. It would be the last party before the Japanese occupied the city, and it went on until 3:30 in the morning.

Just before dawn, Gause departed with a convoy of trucks bearing supplies and communications equipment. Theirs was the last convoy to reach Bataan.

For the next 13 weeks Bataan was the focus of the war in the Pacific. Over 100,000 American and Filipino soldiers and civilians clung to this speck of land while enduring bombing and artillery bombardment day and night.

When the Japanese finally broke through, the thousands of starving and exhausted defenders were rounded up. Rocky Gause found himself in a pen with hundreds of other Americans. He did not fancy life as a prisoner of the Japanese. Sizing up the situation, he overpowered a lone guard and stabbed him with his own knife before running for the bay that separated Bataan from the island of Corregidor three miles away. Bullets zipped around him, but he was able to swim to an offshore wreck where he rested for a few hours. He found a rowboat and continued toward the island fortress.

Saved by Rita

On Corregidor, Gause was assigned to command a machine-gun battery of Filipino soldiers. They endured daily bombardment from Japanese positions surrounding them on all sides. Gause was at his post on May 5 when the Japanese landed on the island. He knew that if he was captured and recognized as the man who killed a Japanese guard it would not go well for him. He vowed to escape.

Gause and a Filipino officer found a small native boat and waited for dark before pushing off into Manila Bay. In the morning their little craft was spotted by a Japanese Zero fighter and strafed. The boat was sunk and his buddy mortally wounded. Gause swam on and reached the distant shore in the gathering twilight. After his exhausting 12-hour journey he fell into a deep sleep. He was awakened near dawn by kicks from Japanese soldiers on patrol. But Gause was so exhausted that his body lay as if dead. Satisfied that he was just another dead American the Japanese moved on.

Gause tried to get off the beach but kept running into Japanese camps or patrols. Just as he thought he was done for, an 11-year-old Filipino boy rescued him. The boy led him to a hastily built shack where he was nursed back to health by the boy’s family. Gause slept for days, and when he awoke he recognized the boy’s sister, the same Rita Garcia he had last seen at the Manila Hotel on New Year’s Eve.

Gause regained his strength under Rita’s watchful eye. Toward the end of May he decided it was time to move on. The longer he stayed with Rita’s family the greater their danger became. Rita helped find a small sailboat. Together they provisioned it and sailed away from Luzon.

Gause hoped the boat would take them to Mindoro, an island south of Luzon, but neither of them had any experience as sailors and after an exhausting night (they dared not sail during the day) they made it as far as the island of Lubang, 25 miles southwest of Manila Bay. Fortunately, Rita had connections on the island, and Gause was hidden from the small but vigilant Japanese garrison.

Americans on the Run

While on Lubang, Gause befriended Jose Ramos, a local contractor. Ramos was a Spaniard, and as a European from a fascist country he had more freedoms than the native Filipinos. He invited Gause to visit occupied Manila disguised as a fellow Spaniard. Gause agreed, and the two men set off on an adventure that ended in a round of drinking with Spanish-speaking Japanese officers.

Shaken by the experience, Gause retreated to Lubang. There he was informed that another American officer was on a nearby island. He set sail at once with a native boy as guide and found a Colonel Wells living comfortably among the Filipinos. Gause stayed with him for two weeks.

While Gause was with Wells, another American wandered into their camp. Captain William Lloyd Osborne had commanded a Filipino infantry company before escaping from Bataan and hiding in the jungle. He and Gause would be inseparable for the next five months.

When Gause introduced Osborne to Wells there was immediate tension. Later that evening, Osborne told Gause that Wells was a Nazi spy. With no other place to go, the two remained guests at Wells’s home. Two nights later Gause fought Wells for possession of a pistol. It went off and shot Wells in the stomach.

Gause and Osborne fled into the night.

Leaving Lubang on the Ruth-Lee

Once again Gause found himself on Lubang, but the situation had changed. In the two weeks of his absence the Japanese had looted the island of food, livestock, fishing boats, and medicines. The islanders were reduced to poverty. Yet, they were determined to help the two Americans escape to Australia.

The Japanese had confiscated a 20-foot motorized skiff, but its balky engine forced them to abandon it. The boat’s owner offered to help the Americans liberate it for use in their getaway. It was an aged and leaking boat that the two Americans christened the Ruth-Lee after their wives. The next few days were spent sewing flour sacks into sails, mounting a mast, chipping, patching, and refurbishing the Swedish-built diesel engine, which they nicknamed the “little Swede.”

When all was ready, Gause had to give Rita the bad news. She had saved his life on several occasions, but he could not take her with him. It was too dangerous. Sadly she went ashore. He never saw her again. Then the two men got under way in earnest.

Even though Osborne outranked Gause, he had no jungle experience and had never sailed. While on board the Ruth-Lee, Gause would be the captain while Osborne tended the engine, cooked, patched leaks, and bailed water, which never stopped seeping into the boat.

Their first stop was at a Japanese-controlled lighthouse where it was said quantities of kerosene could be found. As the little Swede needed fuel oil, a risky raid was necessary. On a stormy night Gause and his mate broke into the lighthouse, overpowered the Japanese keeper, and made off with 55 gallons of precious kerosene. They were on their way to Australia, 3,200 miles away.

The engine ran poorly, and after a few days refused to work at all. Supplies and water were running low when the two itinerant sailors decided to put in at the island of Culion. A town there housed a large leper colony. The two figured correctly that the Japanese would keep their distance. There was a township next to the colony that housed American doctors and about 500 Filipino workers and relatives who cared for the 5,000 lepers.

The sailors found enthusiastic help from the little township. A mechanic went to work on the engine and the propeller shaft, which needed straightening. Electrical output on Culion was limited to one hour a day due to a limited supply of fuel oil to power the local generator. It was during that hour that welding and cutting operations were conducted on the boat. Scraping and caulking continued at other times, and the two American fugitives were feted by the local community in relative safety from the Japanese who were afraid to set foot in the town.

Sailing Through Monsoon Season

With an overhauled motor and replenished supplies, the Ruth-Lee set sail once more for the south and freedom. The sailors had not reckoned with the stormy monsoon season. Traveling at night as they usually did, they were not far from Culion when the wind started blowing and the waves began tossing them about. The two used their limited knowledge of the sea to head into the wind and swells to keep the little boat from being swamped. They tied themselves to the boat to avoid being washed overboard.

With the single-minded goal of staying afloat, they failed to notice their approach to a hidden reef until the Ruth-Lee slammed hard against the rigid coral, lifted up, and slammed again. Osborne was thrown about the cabin where he was tending the engine. Gause barely held onto the tiller. They stuck fast to the reef until dawn when the winds calmed and they were able to jump overboard and guide the leaking boat to the shore. The coral gashed their bare feet and legs as they manhandled the boat off the reef.

It took two days to patch the leaks and holes in the hull before they launched the boat anew into the wind-tossed waves. During the day the churning waters revealed the presence of more dangerous reefs. Gause estimated that the Ruth-Lee ran aground as many as 20 times, requiring a standard two days of repair each. To add to the misery of the trip, Gause, landing on an island in search of water and food, waded through what he reckoned was poison ivy. The pain and stinging lasted for two weeks.

On several occasions Japanese patrol boats and at least one submarine cruised nearby. The sailors’ homemade Japanese flag served them well. The guardians of the Japanese Empire almost always ignored them. Only once did patrol boats give chase, but the Ruth-Lee was able to hide under the jungle overhang of numerous small islands along the coastline until dark and quietly slip away under sail.

One day the men noticed that a shark was following them. It glided along behind the boat all day and was still there the next morning. The men shot at the shark with pistols to no avail. Gause then fashioned a hook from some wire and baited it with dried meat. They hauled in the eight-foot killer and ate the meat.

Leaving the Philippines

Around mid-September the Ruth-Lee had reached the southernmost point of the Philippines and was ready for the ocean journey to Australia via Borneo. The engine once again underwent some field repair in a native village and chugged out to sea.

It was not long before a storm blew up in the night and became a genuine typhoon. For two days and nights Gause struggled to hold the tiller into the wind to keep the boat from swamping. Osborne bailed continuously with a five-gallon can. At the point of total exhaustion, Gause spotted a small island and doggedly pushed the creaking, leaking boat into its lee. Gaining some protection from the howling winds, the two men waited out the storm. Once again they beached their boat. After a few days of rest and repair to the battered hull, the sailors shoved off again for Borneo.

Once away from the Philippines the two American castaways could no longer communicate with the native populations they met. If they flew the Japanese flag, whole villages would empty, their residents fleeing for the hills. In such situations, Gause decided to act Japanese, and they looted what they could find. He thought that if they acted like the Japanese the locals would blame the thievery on the enemy.

The long days of close confinement led to disputes and arguments. Whole days went by with the two men not speaking to each other. In emergencies, however, their teamwork was seamless.

One More Journey on the Open Seas

By early October the two survivors had reached the southern coast of Timor. They had one last open ocean journey to reach the safety of Australia. They had long ago run out of the precious kerosene to power the little Swede. The hardy diesel engine now ran on pure coconut oil, which also served as lubricant. There were still days when the cranky engine would not turn over and progress was measured with slow but steady wind power.

On this last leg of their adventure, they sailed under the flight path of Japanese bombers roaring to and from Australia. Their Japanese flag could no longer protect them, and they were sure they had been spotted. One evening they made out a destroyer in the distance. They hoped that it was an Allied ship, but it soon launched search planes in the gathering darkness. Gause turned off the engine and lowered his sails to give as small a profile as possible.

The planes swept the growing darkness with powerful searchlights, which came close but never found the Ruth-Lee. The next morning brought a rain squall with a protective layer of clouds. It cleared in the afternoon, and as soon as it did a Japanese fighter plane spotted them and began a strafing run. Osborne was grazed in the shoulder by a bullet, and a dozen holes went through the already leaking Ruth-Lee. The burst started fires in the hold, and the little boat began settling as water rushed in.

Fortunately, the rising water put out the fires. Osborne began bailing as fast as he could. Gause cut plugs from their fishing pole and dived into the water to jam them into the leaks. Once that was done, both men bailed until they were able to keep ahead of the leaking.

“Well I’ll be Damned”

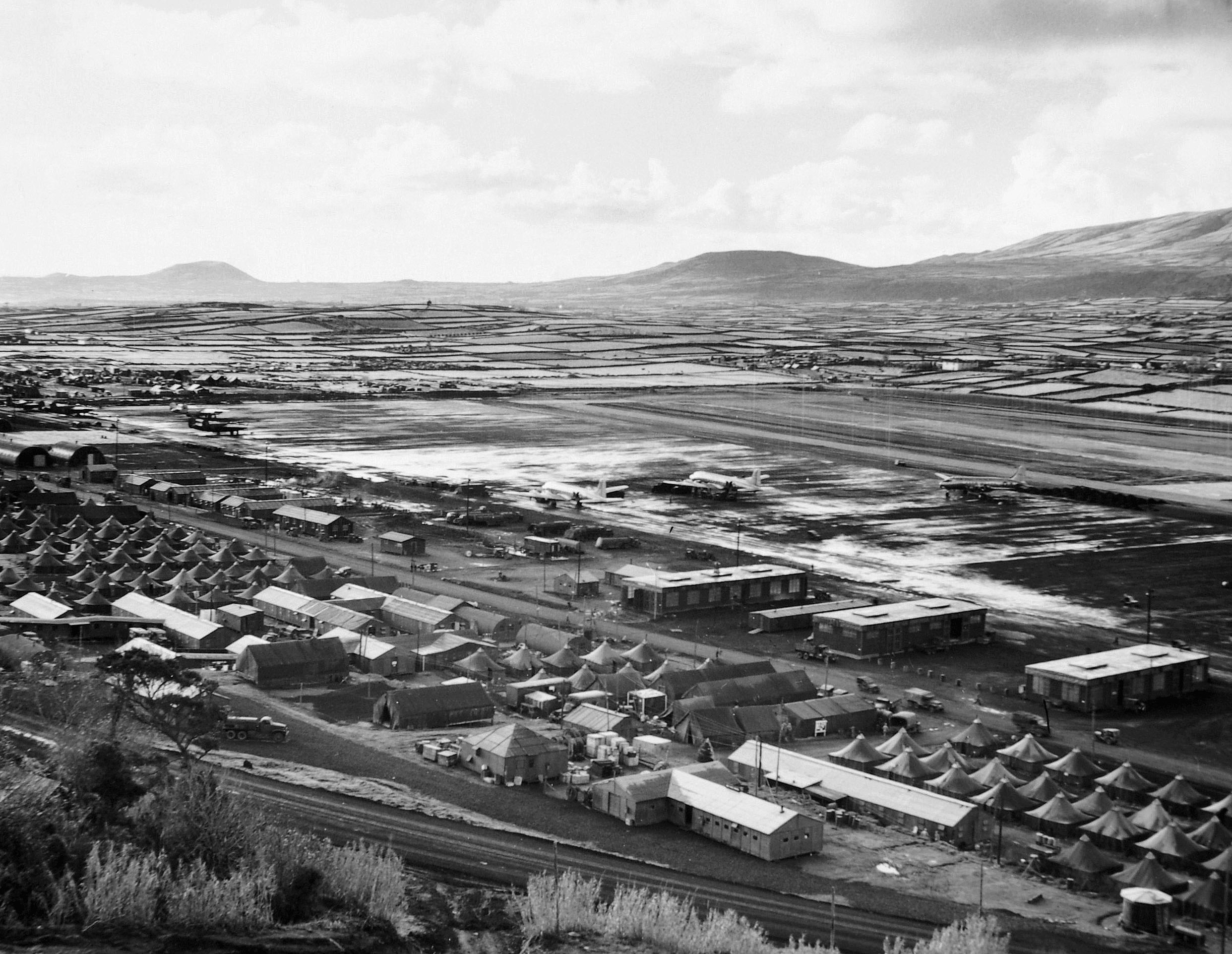

Three more days of uneventful sailing brought them to Australia, where soldiers greeted the battered boat and its dirty, disheveled crew with suspicion until they realized that they were Americans. Soon, the adventurers were whisked away to the Brisbane headquarters of General MacArthur. Gause and Osborne had been barefoot for five months and could not abide the shoes they were given or the ill-fitting clothes provided by the obliging Australians. They sauntered into the general’s hotel headquarters barefoot and wearing the tattered clothes from their trip.

“Sir, Lieutenant Gause reports for duty from Corregidor,” said the tired veteran to the general, five months after the fall of the island fortress. MacArthur returned his salute, looked the tired survivors over, and said simply, “Well I’ll be damned.”

MacArthur personally awarded Gause and Osborne the Distinguished Service Cross. The two were returned to their families on the mainland and stumped for War Bond drives. Both itched for action. Gause was eventually promoted to major and sent to England, where he learned to fly Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighters. While on a training mission in March 1944, he crashed and was killed.

Osborne accepted an assignment in Burma commanding a battalion of Merrill’s Marauders. He survived the war to retire as a full colonel. He later served as an adviser to the South Vietnamese government and died in 1985.

Amazing story. I wonder if it was embellished in some places though..