By Michael D. Hull

After his heady series of victories in the spring and early summer of 1940, Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler was in for a frustrating six months.

With lightning blitzkrieg campaigns, his armies had vanquished the Low Countries—Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg—and France, where the Vichy puppet government had been set up. Yet an eventual triumph over Great Britain remained, even in his mind, less than certain. Royal Air Force Fighter Command mauled Luftwaffe bomber formations sent to soften up the island nation before an invasion, and opportunities to deal Britain a mortal blow in the Mediterranean Sea had been missed. There, the Royal Navy held the lifelines, while in the Western Desert a British army had destroyed Italian forces three times its size. Hitler and his high command had to devise peripheral ways to “break the British will to resist.” Strung out thinly and standing alone against the Axis powers, the British had to be isolated and the Mediterranean closed to the Royal Navy.

Besides Russia and Japan, it was principally from Italy and Spain that Hitler’s military chief of staff, General Alfred Jodl, hoped for military support to bring about this desired end. He suggested mining the Suez Canal or inducing Spain to capture Gibraltar with German aid, a suggestion that opened up vistas of carrying the war to the Atlantic islands and vital shipping routes.

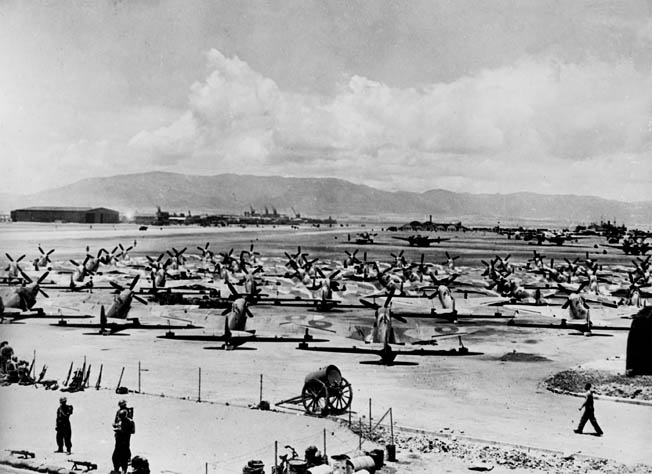

Gibraltar was the fulcrum. Captured by Britain in 1704 during the War of the Spanish Succession, retained by treaty in 1713, and made a crown colony in 1830, Gibraltar guarded the narrow entrance to the western Mediterranean from the Atlantic Ocean. A great 1,398-foot rock honeycombed with 25 miles of tunnels containing supply and ammunition dumps, workshops, offices, and barracks, Gibraltar was the only Western Allied stronghold on the European continent until 1943. It was the home base of the Royal Navy’s powerful Force H, and convoys for Egypt and Malta were organized from there. In time it was to play a crucial role during the long siege of Malta and in the Allied invasion of North Africa. Gibraltar also housed the then headquarters of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of Allied forces in the Mediterranean Theater, and its airstrip extending into the sea was crammed with 600 aircraft used to cover the landings.

In 1940 Hitler could not foresee Eisenhower, but Spain’s President Francisco Paulino Franco was a sharp thorn in his side and in the side of his military advisers. Although Spain had joined the Anti-Comintern Pact of November 1936, under which Germany, Japan, and Italy agreed to threaten the Soviet Union from both east and west, Franco had had no second thoughts since he declared neutrality when World War II broke out on September 1, 1939. Hitler’s many reasons for wanting him in his camp were artfully met by the Spanish leader, who set a

high asking price for his country’s belligerency and kept raising it.

Gibraltar regularly drew air attacks by Italian and Vichy French bombers and sabotage raids by Italian naval units. Crippling Britain was the aim, dependent as she was on manpower and raw materials from India and her other eastern colonies, shipped by way of the strategic Suez Canal and past Gibraltar. As British Prime Minister Winston Churchill observed later, “Spain held the key to all British enterprises in the Mediterranean,” since Gibraltar was regarded as indefensible in the event of aggression by Spain.

“All We Wanted Was the Neutrality of Spain”

Spain’s Franco, commonly referred to as “El Caudillo,” was in a league by himself. Cool-headed, calculating, and subtle, he knew that Spain’s interests would not be helped by belligerency. Three years of civil war had left his country’s economy in tatters and its people literally dying of starvation. “They had had enough of war,” Churchill would write later. “A million men had been slaughtered by their brothers’ hands. Poverty, high prices, and hard times froze the stony peninsula.”

All that notwithstanding, reasons of geography brought pressure from both the aggressors and the Allies to be exerted on Spain for assistance to each side. “All we wanted was the neutrality of Spain,” Churchill explained. “We wanted to trade with Spain. We wanted her ports to be denied to German and Italian submarines. We wanted not only an unmolested Gibraltar, but the use of the anchorage of Algeciras for our ships and the use of the ground which joins the Rock to the mainland for our ever-expanding air base. On these facilities depended in large measure our access to the Mediterranean.

“The attitude of Spain was of even more consequence to us than that of Vichy, with which it was so closely linked,” Churchill added. “Spain had much to give and even more to take away. We had been neutral in the sanguinary Spanish Civil War. General Franco owed little or nothing to us, but much—perhaps life itself—to the Axis Powers. Hitler and Mussolini had come to his aid. He disliked and feared Hitler. He liked and did not fear Mussolini. At the beginning of the World War, Spain had declared, and since then strictly observed, neutrality. A fertile and needful trade flowed between our two countries, and the iron ore from the Biscayan ports was important for our munitions.”

The Diplomatic Battle Over Spain

Born in Galicia in 1892, the short, stocky Franco had graduated with honors from the Toledo Military Academy in 1910 and distinguished himself in fighting against Moroccan insurgents. He was known for “incomparable bravery and for extraordinary good luck under fire.” A rightist, puritanical martinet, he served as governor of the Canary Islands and commanded the Spanish Army of Africa after it revolted. His capture of Melilla, Spanish Morocco, on July 18, 1936, touched off the Spanish Civil War. Three years of bloody conflict ensued, during which he defeated the Communists and preserved Catholicism. Franco became absolute dictator on August 4, 1939.

Fearing that the Spanish leader might succumb to German pressure, the British sent a new ambassador to Madrid on June 1, 1940. Sir Samuel Hoare’s mission was to plan the evacuation of the British diplomatic and business colony there and to do all he could to prevent Spain’s entry into the war on the German side. Sir Samuel met with the Spanish foreign minister, Juan Beigbeder, a former German sympathizer who was now convinced that his country needed to stay neutral. An agreement was reached on June 24, 1940, to extend the British-Spanish trade pact.

Meanwhile, the German hope was that Generalissimo Franco would declare belligerency after resolving his country’s economic difficulties. Gathering his generals at the Berghof, his mountaintop retreat in southeastern Bavaria, on July 13, Hitler announced that he intended to draw Spain into the war “in order to consolidate the front against Britain from the North Cape to Morocco.” That same month, he told Italian high officials that the German staffs were thinking “very seriously” about the possibilities of attacking Gibraltar. Code-named Operation Isabella-Felix, Hitler’s plan called for the capture of Gibraltar, the Spanish Canary Islands, and the Portuguese Cape Verde Islands.

Hitler’s directive was clear-cut: “Political measures to bring about the entry into the war of Spain in the near future have been instituted. The aim of German intervention in the Iberian Peninsula will be to drive the English from the western Mediterranean. (a) Gibraltar is to be captured and the Straits closed; (b) the English are to be prevented from gaining a foothold at any other point on the Iberian Peninsula or in the Atlantic islands.”

Franco sent envoys to talks in Berlin at which Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s arrogant, bumbling foreign minister, casually mentioned that Germany wanted to annex one of the Spanish Canary Islands for a naval and air base. It was useful information, for Franco.

The Enigmatic Wilhelm Canaris

Among those in the German high command working on the plan was the short, rumpled Admiral Wilhelm Franz Canaris, head of the Abwehr military intelligence service. Cultured, brusque, and enigmatic, he was known for his keen intelligence and sober judgment. Hitler picked him to negotiate with Franco.

“Willie” Canaris, brought up in a wealthy and happy Westphalian family of right-wing but liberal Protestants, had distinguished himself in the Imperial German Navy during World War I. He skippered a U-boat in the Mediterranean, became addicted to espionage, and eluded British and Italian counterintelligence. It was rumored that he once met the legendary Mata Hari in Spain.

Canaris had mastered Spanish and performed veritable feats of espionage in Italy and Spain. He retained a lifelong fascination with Hispanic culture. Nicknamed the “Little Admiral” and “Old Whitehead” because of his prematurely white hair, he initially approved of National Socialism, owing perhaps to an intense aversion to communism. But he soon grew suspicious of Hitler’s grand designs and consorted cautiously with anti-Nazi members of the Schwarze Kapelle (Black Orchestra).

As a member of Hitler’s inner circle, Canaris had prepared the way for him in many ways. Before long, though, he became disgusted. During the Sudetenland crisis of September 1938, he called Hitler a “madman,” aware that he was leading Germany to its ruin. Canaris’s upbringing and experience precluded him from espousing the view of conservative contemporaries that the Hitler regime could be controlled; Germany was on a slippery slope toward the abyss.

Torn therefore between his duty as an officer and the demands of conscience, Canaris’s attitude toward the German opposition was ambivalent. He never committed himself to an open coup but did provide the military conspirators with information and protection.

Canaris enlisted Jews into the Abwehr to help protect them, was often in conflict with the infamous Reinhard Heydrich and the SS, and reportedly passed intelligence on Hitler’s invasion plans to MI-6, the British foreign secret service. The extent of his dealings with the opposition would baffle Gestapo investigators until the end. Arrested in July 1944 on suspicion of subversive activity, Admiral Canaris was executed in April 1945.

Negotiating Operation Felix

Back in 1940, though, the Little Admiral was Hitler’s choice to gauge the prospects for Operation Felix. He arrived in Spain on July 23. He and an entourage of Army officers had traveled in civilian dress and with false passports, by different routes. Three houses in Algeciras, the historic seaport six miles west of Gibraltar, were placed at their disposal. Canaris talked with Franco and Spanish military and diplomatic officials and requested maps of the British defense system at Gibraltar.

The Spanish were not encouraging. Franco did not dismiss the German plan out of hand but voiced manifold reservations. He feared the Royal Navy and thought it might retaliate against the Canary Islands. He also stressed his country’s economic woes. To this, Spanish Air Minister Juan Vigón added the observation that a surprise attack on Gibraltar was impossible because only one road led there. It would take time to position the necessary artillery support, and the Spanish railway gauge differed from the French.

The meetings were cordial but yielded little encouragement. Canaris and his advisers spent two days taking a closer look at Gibraltar and frowned at what they saw. The steep slopes and unpredictable winds ruled out glider or paratroop drops, and the isthmus connecting the bastion to the mainland was apparently mined. The defenders would have a good field of fire from all positions.

When the results of the German team’s four-day tour were discussed at a concluding parley on July 27, the outlook was not hopeful. A surprise attack was out of the question, the degree of Spanish commitment was uncertain, and, even if an assault were undertaken, the Spanish would need to make immense preparations to support a German expeditionary corps.

Despite the numerous obstacles, after Canaris and his team returned to Germany work was started immediately on a plan of attack. Hitler approved Operation Felix on August 24, 1940. Franco had agreed to participate, provided that his massive material demands were met, and Canaris notified General Franz Halder, chief of the Army General Staff, of the amount of weapons, grain, oil, rail cars, and foodstuffs that the Spanish leader thought he needed.

Canaris voiced pessimism about the whole endeavor and tried to bring Halder around to his way of thinking. It was the admiral’s firm opinion that Franco would not get involved with Operation Felix until Britain was on its knees, and he advised that it would require a personal visit by the Führer to “work it.” On September 14, Hitler told Halder and Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch, commander in chief of the German Army, that he was keen “to promise the Spanish all they want, even if we can’t deliver in full.”

On September 26, even before the postponement of Operation Sealion (the invasion of England), Admiral Erich Raeder, commander of the German Navy, told the Führer, “The British have always considered the Mediterranean the pivot of their world empire…. Germany, however, must wage war against Great Britain with all the means at her disposal and without delay, before the United States is able to intervene effectively. For this reason, the Mediterranean question must be cleared up during the (coming) winter months.” Raeder proposed the seizure of Gibraltar and the dispatch of forces to Dakar, West Africa, and the Canary Islands.

“The Entry of Spain … Has No Practical Value”

In mid-September 1940, Franco had sent his brother-in-law, Interior Minister Serrano Suñer, to Berlin to assure Hitler that whenever Spain’s supply of foodstuffs and war material was secure, Spain could immediately enter the war. In a receptive mood, the German leader promised that Germany would do everything in its power to help Spain.

Suñer was convinced of Germany’s invincibility, but Franco kept his own counsel. He had told his generals, “I tell you that the English will never give in. They’ll fight, and go on fighting, and if they are driven out of Britain they’ll carry on the fight from Canada. They’ll get the Americans to come in with them. Germany has not won the war.” At the same time, Franco had to exercise care lest he exhaust Hitler’s patience and subject Spain to the fate of Czechoslovakia and the other small countries that had stood in Hitler’s way.

In a letter to the generalissimo, Hitler agreed to “recognize the Spanish claim to Morocco with the one limitation of assuring Germany a share of the raw materials of this area.” The Führer promised military and economic aid “in the highest measure possible for Germany” and suggested that he and the Caudillo should meet to settle the details.

The Spanish leader’s response was prompt and compliant. In a September 22 letter to Hitler, he wrote, “Your esteemed ideas satisfy our wishes.… We believe ourselves to be in complete agreement…. I reply with the assurance of my unchallengeable and sincere adherence to you personally, to the German people, and to the cause for which you fight. In defense of this cause, I hope to be able to renew the old bonds of comradeship between our armies.”

The cordial words and diplomatic soft soap were just that; the letter made no mention of any date for Spain’s entry into the war at Germany’s side. In the Reich Chancellery, Hitler ranted wildly about “the Jesuit swine” and “the false pride of the Spaniard.” During the first two weeks of October 1940, there was increasing disquiet in Berlin over Franco’s delaying tactics, and Hitler’s general staff even considered an assault against Gibraltar without Spanish help. General Halder had doubts about the venture; he thought that Gibraltar might even be taken without a fight, but if that was not the case then it would prove too costly. Other top military advisers placed little value on Franco because of the tattered economic situation in Spain.

German State Secretary Ernst von Weizsacker wrote, “My vote is that Spain should be left out of the game…. Gibraltar is not worth that much to us…. Spain is starving and has a fuel shortage … the entry of Spain … has no practical value.”

Hitler determined otherwise. The significance of having Spain in the fascist Axis was primarily to cover the situation in the Mediterranean and North Africa against the background of Hitler’s planned invasion of Russia and at the same time to relieve British pressure on Italy. Franco needed to be reminded that he owed his triumph in the Spanish Civil War to extensive military aid purchased from Germany and Italy, and the moment to redeem his promise to enter the war if given support was at hand. On October 12, Operation Sealion was shelved and the preparations for Operation Felix intensified.

“This is the Most Important Meeting of My Life”

On October 22, the Führer boarded his special armored train, curiously named Amerika, and left Germany. That evening, the train stopped at Montoire, north of Tours in west-central France, where Hitler conferred briefly with Vichy Deputy Premier Pierre Laval, who came aboard to arrange Hitler’s meeting with Vichy leader Marshal Philippe Pétain on October 24. Then the Nazi leader headed for the little French resort town of Hendaye, just below Biarritz and opposite Irún, on the Franco-Spanish border. As the train rolled southwestward, Admiral Canaris warned Hitler that he would probably be disappointed by Franco, who was basically a hard-bitten diplomat.

The two dictators’ cat-and-mouse game was about to be played out face-to-face. For the ruthless Führer the stakes were high, but the wily Spanish leader had no intention of being ensnared.

On October 23 the German train steamed into Hendaye for the rendezvous with Franco, at the edge of town where the French narrow-gauge and Spanish wide-gauge railway lines met. Hitler arrived in good time for the 2 pm meeting, but there was no Spanish train at the adjoining platform. It was a sparkling autumn day, so the punctual Germans were not annoyed as they stretched their legs, smoked, chatted, and viewed the spectacular scenery. After all, what could one expect from those indolent Spaniards with their interminable siestas?

One hour later, Franco’s train appeared on the International Bridge over the River Bidassoa. The tardiness was not accidental and was not due to any siesta. “This is the most important meeting of my life,” Franco told one of his generals. “I’ll have to use every trick I can, and this is one of them. If I make Hitler wait, he will be at a psychological disadvantage from the start.”

As the Spanish train drew alongside Hitler’s, Franco knew that the fate of his country rested on his ability to keep it out of the European war. But would Hitler let him remain neutral? If he gave the Führer a flat refusal, what could stop a German invasion? He had to cling to some slight point that needed further clarification, while giving the impression of joining the Axis.

Franco Makes His Demands

Franco’s Galician heritage was his armor as he stepped onto the platform and started toward Hitler to an accompanying blast of military band music. With their foreign policy aides in tow, the two leaders headed for their historic parley in Hitler’s saloon coach.

Conducted through interpreters, the meeting would last for almost nine hours. The Caudillo began with a set speech laden with compliments and promises. He said that Spain had always been “spiritually united with the German people without any reservation and in complete loyalty,” and that in the present war “Spain would gladly fight at Germany’s side.”

However, he pointed out that the difficulties of doing so were well known to the Führer, in particular the food shortage and the difficulties that anti-Axis elements were making for his poor country in Europe and America. “Therefore,” said Franco, “Spain must mark time and often look kindly toward things of which she thoroughly disapproves.”

Hitler responded that in return for Spanish cooperation in the war he would let Franco have Gibraltar and some colonial territories in Africa. Offering up evasions while insisting on more concessions, the Spanish leader said his country needed several hundred thousand tons of wheat immediately; was Germany ready to deliver it? And what about the heavy guns Spain needed to defend its coast from possible attacks by the Royal Navy, not to mention antiaircraft guns?

Franco shifted from one subject to another, from recompense for the certain loss of the Canary Islands to the impossibility of accepting Gibraltar as a present from foreign soldiers. The fortress must be taken by Spaniards, he said.

Heated Negotiations

With Franco wanting much and Hitler having little to offer, there was much quibbling. The Führer offered Franco a 10-year alliance and proposed a joint attack on Gibraltar in the new year. The Caudillo replied that Spain would gladly fight at Germany’s side as soon as its military and economic deficiencies had been made good and its political aspirations recognized.

He was less enthusiastic, however, after Hitler told him that, because of the danger of a revolt in French North Africa, Germany could make Spain no promises that might lessen the willingness of Vichy to defend its colonies. Franco answered that he could not afford to accept an alliance that did not guarantee him French Morocco and part of Algeria.

The Nazi dictator then promised that Spain would receive “territorial compensation out of French North African possessions to the extent to which France could be indemnified out of British colonies.” Franco was not entirely satisfied and made no firm commitment. Besides massive economic assistance and shipments of equipment to strengthen his weak army, he demanded rectifications of the Pyrenees frontier and the cession of French Catalonia (French territory once historically linked with Spain but actually north of the Pyrenees), Algeria from Oran to Cape Blanco, and virtually the whole of Morocco.

Hitler insisted doggedly on Spanish belligerency, submarine bases, and the green light from Madrid for an assault on Gibraltar. With time taken out for dinner in Hitler’s special dining coach, the imperturbable Franco spoke at length in a monotonous, singsong voice, standing firm on every important point as his host became increasingly exasperated. At one point, as he had done with British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain at Munich in 1938, the Führer sprang up from his chair and exclaimed that there was no point in continuing the conversations.

At the end of the day, after hours of haggling about honors and rewards, Hitler and Franco produced a secret protocol. Under this agreement, Franco vowed to enter the war at his own convenience. Hitler promised to meet Spanish economic and territorial demands, but only if France could be compensated at the expense of the British.

Ironically, the only beneficiary, indirectly, was Britain, whose situation in the Mediterranean was left intact.

“We Cannot Do Anything With This Guy”

Hitler was fuming when he left his dining car. “Franco is a little major!” he told Admiral Karl-Jesko von Puttkamer. To his valet, Heinz Linge, he reduced Franco further in rank: “In Germany, that man would never rise higher than sergeant!” Yet another in the Führer’s entourage heard him lower the Spanish generalissimo to corporal, Hitler’s own grade in World War I.

As he left Hendaye, the exhausted Hitler murmured, “We cannot do anything with this guy.” He reported later to Mussolini, “Rather than go through that again, I would prefer to have three or four teeth taken out.”

Despite many platitudes gushed by the German and Spanish press, the historic meeting was a bust for Nazi diplomacy. Foreign Minister Ribbentrop, who had tried to bully Suñer like a schoolmaster, said of Franco the following morning, “That ungrateful coward! He owes us everything and now won’t join us.”

War Directive 18

Pretense was kept up, though, and the Hendaye talks were held to have been a promising prelude to Spain’s entry into the war. Hitler ordered the preparation of War Directive 18, which included blueprints for the invasion of Gibraltar and the deployment of forces in the Canary Islands, the Portuguese Azores, and French North Africa. As soon as the first German troops had crossed the Spanish border, Luftwaffe planes would attack Royal Navy ships in Gibraltar harbor.

The Wehrmacht’s 22nd Infantry Division was fitted out, leave restrictions were imposed, and additional troops were readied for a possible invasion of neutral Portugal, whose long Atlantic coastline would be ideal for U-boat bases. A lightning blitzkrieg operation was out of the question because the German forces would need 38 days in which to move down to Gibraltar from the French border. The first advance commandos were to enter the Iberian Peninsula on December 6, 1940, and the main force would attack early in 1941.

As the German preparations became hectic during November 1940, Admiral Canaris watched with some concern. Stationed in Spain from November 12 onward, he was particularly alarmed by Halder’s zealous plan calling for two large advance commando groups to proceed under cover through France—in civilian clothing and riding in French vehicles—and enter Spain under false identities. There would also be German artillery and supply officers in the cities of Seville and Cadiz, and Canaris was sure they were all bound to be detected by British intelligence.

As the month progressed, the Germans started a series of secret operations around Gibraltar. Admiral Canaris sent a naval officer to Algeciras to determine the best location for heavy coastal batteries to support an attack, while other German officers scouted for naval intelligence on Gibraltar’s weak points. Canaris drew upon his considerable knowledge and contacts in Spain, and did much cloak-and-dagger work in planning the operation. Yet, he astounded his influential Spanish friends by confiding to them that he believed Germany would ultimately lose the war.

Operation Felix on Hold

On December 7, 1940, the Spanish leader handed another rebuff to Hitler. On that evening, Admiral Canaris had an audience with the Caudillo in Madrid. Canaris relayed Hitler’s desire to commence the attack on Gibraltar soon and requested approval for the transit of troops on January 10, 1941, when promised German aid shipments would also begin arriving.

Ever attentive, Franco was aware that the Luftwaffe had failed to achieve air supremacy over England and that the Italian position in the Balkans was growing worse by the day. And he knew his own problems only too well. The winter of 1939-1940 had been difficult, but the winter of 1940-1941 became known in Spain as the year of hunger. Widespread rumblings of discontent were a constant worry.

Accordingly, the Caudillo told Canaris that he could not fight a long war; it would demand intolerable sacrifices of his people. Furthermore, Franco explained to the admiral, it was impossible for Spain to enter the war on the date set because of the threat of British naval retaliation, his lack of armaments, and the critical supply situation. When Canaris asked him when the transit of German troops would be possible, the Caudillo was unable to provide a date.

Canaris returned to the German embassy and sent a telegram conveying Franco’s response to Hitler. The Caudillo had demanded that Germany make the preparations for the Gibraltar assault under conditions of the strictest secrecy and disguise. This was a diplomatic smoke screen. For the second time, Franco was rejecting a direct request from Berlin for Spanish belligerency. On December 10, 1940, Canaris spelled it out for the German high command: “The Caudillo has given us clearly to understand that he cannot enter the war until Britain is on the verge of defeat.”

After Franco’s stalling tactics and refusals during the autumn and winter of 1940-1941, Hitler relegated Spain and the Mediterranean situation to the back burner of Axis politics. A month after he had issued his November 12 directive, he quietly ordered that Operation Felix be dropped “because the political conditions no longer exist.” The Führer’s ambition to close the Mediterranean to the Royal Navy was never achieved. He did, however, maintain operational plans for Felix’s possible revival.

“Spain Does Not Want to Enter the War”

Spain was spared from Hitler’s well-known wrath by Italian blunders in the Balkans and defeats at the hands of the British in North Africa, and by the Nazi dictator’s increasing preoccupation with Operation Barbarossa, his plan for an imminent invasion of the Soviet Union.

Although he refused to permit the transit of German troops for an assault on Gibraltar, Franco did accommodate German diplomatic priorities through the de facto and de jure recognition of Nazi puppet regimes and by continuing to allow the use of his country as a forward base for U-boats and spies.

It was distasteful to him, but Hitler made one final effort to influence Franco. In a long letter to the Spanish leader on February 6, 1941, the Führer wrote, “About one thing, Caudillo, there must be clarity: we are fighting a battle of life and death and cannot at this time make any gifts…. The battle which Germany and Italy are fighting will determine the destiny of Spain as well. Only in the case of victory will your present regime continue to exist.”

Unfortunately for the Axis, Hitler’s letter reached Franco on the day that Marshal Rodolfo Graziani’s remaining Italian forces in Cyrenaica were wiped out by the British Eighth Army south of Benghazi. When the Caudillo got around to replying to the Führer on February 26, 1941, he professed his “absolute loyalty” to the Axis Powers but reminded Hitler that recent developments in the Mediterranean theater had left “the circumstances of October far behind,” and that their Hendaye understanding had become “outmoded.”

On one of few occasions in his stormy, odious career, Hitler was forced to concede defeat. “The long and short of the tedious Spanish rigmarole is that Spain does not want to enter the war, and will not enter it,” he told Mussolini. “This is extremely tiresome since it means that for the moment the possibility of striking at Britain in the simplest manner, in her Mediterranean possessions, is eliminated.”

The Fighting Spanish Soldiers of World War II

Meanwhile, despite its neutral stance, Spain did play a partial role in World War II operations. Formed from the Falangist (Fascist) Party, the volunteer Blue Division served with the German Army when Hitler invaded Russia on June 22, 1941. Initially numbering 17,692 officers and men, and commanded by Maj. Gen. Augustin Munoz Grandes and later Maj. Gen. Esteban Infantes, the division reached Germany in July 1941. Its blue-shirted troops swore allegiance to Hitler, although the wording was modified to specify that they were engaged only in “the battle against Bolshevism.”

From October 1941 to February 1943, the German-equipped Blue Division’s infantry and artillery regiments fought at Lubkovo, Kurisko, Leningrad, and Krasny Bor, where they suffered 2,253 casualties. Allied pressure and a shift in Spanish policy brought about the return of the division from the Eastern Front, with the last volunteers reaching Spain by the end of 1943. But the smaller Spanish Legion, comprising volunteers from the Blue Division, remained in Russia until the spring of 1944.

Of the estimated 47,000 Spaniards who served at different times in the division, 22,000 became casualties and 4,500 died. Fewer than 300 prisoners of war were eventually evacuated from the Soviet Union in 1954. Many who served in the division received German and Spanish decorations for bravery.

Spanish airmen also fought on the Eastern Front. Five Blue fighter squadrons served consecutively with German Army Group Center. Providing support for German bombers, they shot down 156 Soviet planes and lost only 22 men missing or killed before returning home with the Spanish Legion.

On the other side during World War II, many Spaniards were active with French Resistance groups in southern France, thousands fought in the Zouave regiments of the French Army of Africa, and about 70 belonged to the legendary British Commando group, Layforce, in the ill-fated Crete campaign.

Ultimately, thanks to the actions of the artful President Franco and the enigmatic Admiral Canaris, Spain and Portugal were not violated by the Nazis, Gibraltar stood firm, and Britain’s precarious hold on the Mediterranean lifeline prevailed. Supported in time by American forces, British strength brought about the defeat of the Axis powers in North Africa and the eventual liberation of Sicily and Italy. Much was owed, Churchill would admit, to the “duplicity and ingratitude” of Franco’s dealings with Hitler and Mussolini.

“Spain held the key to all British enterprises in the Mediterranean,” wrote the prime minister, “and never in the darkest hours did she turn the lock against us.”

Short evaluation of the Hitler-Franco relationship was that Franco knew his objectives and limitations and Hitler was delusional about both in his sphere. The benefit to the West was almost equally during the war operations and afterward in preventing the Communist destabilization of several countries that were under domestic pressure.