By Roy Morris Jr.

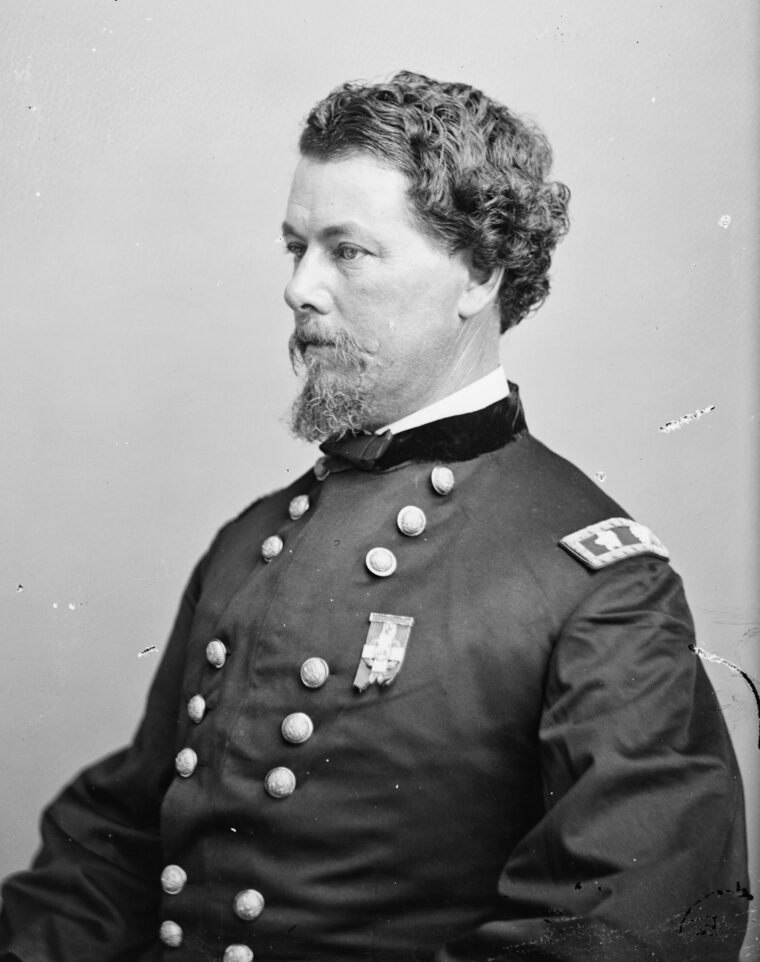

Phil Sheridan had a bad feeling. The bantam-sized Union general always trusted his instincts, and now, in mid-October 1864, those instincts were telling him that trouble was brewing back at the front, where his Army of the Shenandoah was encamped near Cedar Creek, Virginia, resting and relaxing after a busy few weeks burning civilian farms and slaughtering thousands of head of livestock from Staunton north to Woodstock. The premeditated orgy of destruction, which residents of the Shenandoah Valley would remember for decades afterward as “The Burning,” was intended to deny food and supplies to the hard-pressed Confederate defenders in the valley. It had been presaged by two significant victories by Sheridan’s forces in the past month, at Winchester and Fisher’s Hill, opening the way for Union troops to devastate the region known as “the Confederacy’s breadbasket.” “When this is completed,” Sheridan had boasted to his superiors in Washington, “the Valley will have but little in it for man or beast.” While his soldiers looted and burned, Sheridan rode behind them in a jaunty two-seat wagon, waving a cigar and urging them on.

Sheridan’s forces now were camped near the historic Belle Grove plantation, a colonial-era mansion that had been the home of Major Isaac Hite, brother-in-law of President James Madison and friendly neighbor of President Thomas Jefferson, who had personally designed the limestone dwelling for Hite in 1794. While the soldiers idled about their tents, Sheridan made a lightning-quick trip to Washington to discuss future strategy with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and General-in-Chief Henry Halleck. Not wanting to be away from his army too long, Sheridan had arranged to have a special train standing by to take him and his staff back to Martinsburg as soon as the meeting was over. They spent the night of October 17 in Martinsburg, then rode 28 miles west to Winchester, where they spent another night at the home of local tobacco merchant Lloyd Logan. Before turning in, Sheridan sent a message to Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright, whom he had left in temporary command of the army at Cedar Creek. Wright sent back word that everything was quiet; he planned to reconnoiter enemy positions early the next morning. Sheridan, relieved, went to bed for the night.

Crossing the Icy Shenandoah

While Sheridan slept, the Confederates in Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s Army of the Valley (II Corps), detached from Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, were up late, preparing a nasty surprise for the Union occupiers of the Shenandoah Valley. Twice in the preceding month, Early’s defenders had been smashed by Sheridan’s forces, embarrassing routs that had driven the Confederates back into the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains and left the harvest-laden valley unprotected. Early, a hard-drinking, irreligious old infantryman, intended to reverse those defeats and once again, in his words, “Scare Abe Lincoln like hell.”

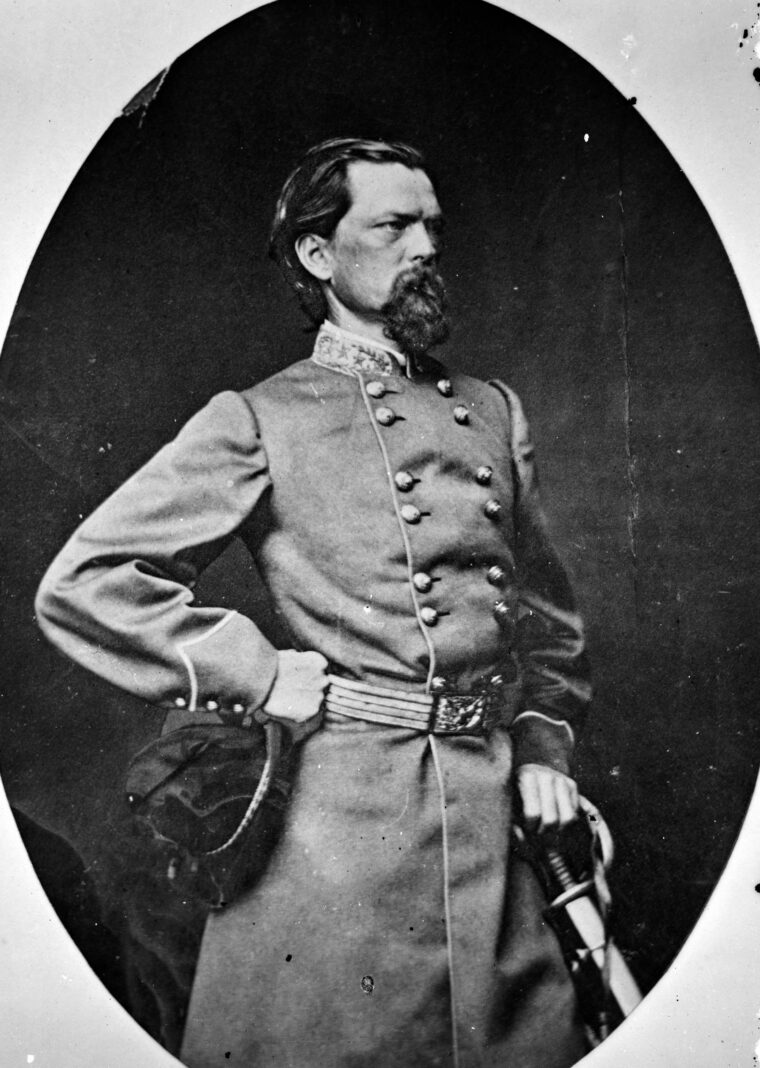

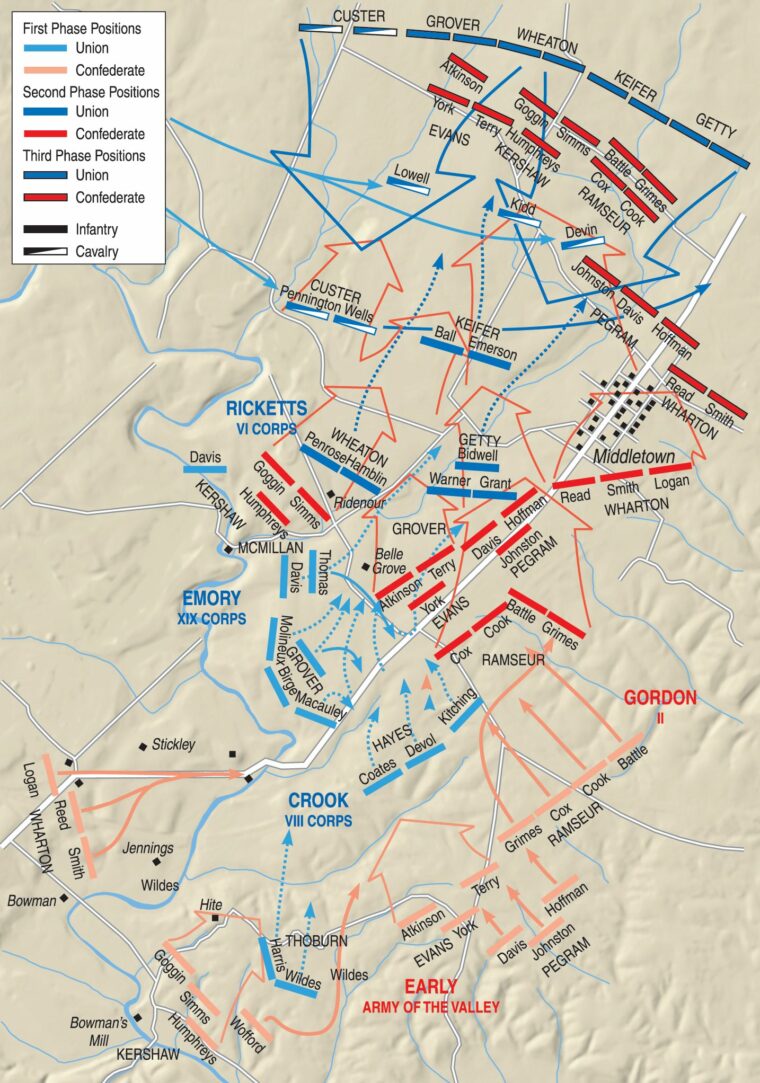

To do so, Early turned to Georgia-born Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon, his senior division commander. With the help of Stonewall Jackson’s former mapmaker, Captain Jedediah Hotchkiss, Gordon devised a plan to strike the left flank of Sheridan’s army. Protected—so they thought—by steep-sided Massanutten Mountain, the Union commanders had left the flank comparatively undefended. But Gordon and Hotchkiss had personally scouted the area, dressed as farmers, and had discovered a narrow “pig path” that wound across the mountain. By marching single-file in the dead of night, Gordon’s three divisions, 7,000-strong, could clear the mountain, ford the waist-deep north fork of the Shenandoah River, and fall upon the enemy flank like avenging angels—or devils, depending upon which side you were on. “Striving to suppress every sound,” Gordon recalled, “the long gray line like a great serpent glided noiselessly along the dim pathway above the precipice.” To reduce noise, the soldiers had left their canteens behind, and the officers had similarly abandoned their swords.

It was hard going for the Confederates, who had to thrash their way in the dark through thick tangles of brambles and stumble over loose chunks of shale and fallen logs. Already chilled by having to wade across another stream three miles to the rear, the Southern soldiers lay down on in the tall weeds on the south bank of the river to wait for two other Confederate infantry divisions to get into position farther west while gray-clad cavalrymen rode around behind the enemy rear. The simultaneous attack was slated to begin just before dawn. Gordon could hardly wait. “The destruction of Sheridan’s army,” he felt, “was inevitable.”

At 5 am, Gordon ordered his men to ford the river. The water was so icy, even in early fall, that one Confederate in the 31st Virginia Infantry compared it to cutting off his legs at the water line. Nevertheless, the Southern troops slid into the river and quickly waded across, forming into battle lines as soon as they emerged dripping from the water. The jumping-off point for the attack was the Cooley homestead a mile beyond the river. Gordon’s three divisions were shaped like a spear point: Maj. Gen. Stephen Dodson Ramseur’s division was on the right, with Brig. Gen. Clement A. Evans temporarily commanding Gordon’s own division on the left. Behind Evans was Maj. Gen. John Pegram’s division in reserve.

“Another Union Victory!”

While Gordon’s strike force massed on the unsuspecting Union left, Maj. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s division launched a diversionary assault on the Union left-center and Brig. Gen. Gabriel Wharton led another attack on the Union center along the macadamized Valley Turnpike. Several miles to the west, two brigades of Confederate cavalry galloped forward to strike the Union right. The attacks went off at almost exactly the same time, catching most of the enemy soldiers still asleep in their tents. Major D.A. Grimsley, part of a 300-man detachment that was riding north toward Belle Grove plantation to personally capture Sheridan where he was believed to be headquartered, heard the initial volleys that opened the battle. “It was not ushered in by a few preliminary shots, as was generally the case,” Grimsley recalled, “but it was a prolonged roll, without cessation, for apparently five minutes. After the volley was over the echo of it seemed to roll back and forth over the Valley a half dozen or more times. When it had once died away it would return to you again from another direction.”

Union soldiers in the center, who had the protection of breastworks, trenches, and abatis, put up a brief fight before being overwhelmed. “Another Union victory!” the Confederates jeered as they broke through the defenses. Union Colonel Joseph Thorburn was shot down and killed as he attempted to rally his men. Meanwhile, on the far left, Gordon’s column rolled through the isolated camp of the 9th West Virginia Regiment, almost before the Federals knew what was happening. “They jumped up running,” recalled Private G.W. Nichols of the 61st Georgia, “and did not take time to put on their clothing, but flee in their night clothes, without their guns, hats or shoes.” Beyond the camp was the Union wagon park, whose teamsters were huddled in a steep ravine to escape the fire. “Poor fellows,” remembered Shadwell of the 31st Georgia. “It looked like murder to kill them huddled up there where they could not defend themselves, while we had nothing to do but load and shoot.” Those Union troops who survived the first volleys scrambled up the far side of the ravine in a desperate bid to escape. “Their knapsacks on their backs presented a conspicuous target for our rifles,” said Shadwell. “I was surprised as I crossed the ravine to see how few of them were killed.”

Covering the Union Retreat

Soon the entire left wing of Maj. Gen. George Crook’s Union VIII Corps broke for the rear, uncovering the left flank of the neighboring XIX Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. William Emory. Emory’s corps was sheltered behind a formidable set of breastworks, fortified by steep piles of dirt and protected in the front by a sharp pine abatis and a 15-foot-deep ditch. Cedar Creek itself wound in and out of the breastworks. It was, a Confederate attacker said, “One of the most completely fortified positions by nature, as well as by hand, of any line occupied during the war.” The disintegration of the VIII Corps, however, left the men of the XIX Corps in danger of being enveloped on all sides. Emory, thinking quickly, sent one brigade forward to slow the Confederate advance and ordered Colonel Edward L. Molineux to move his brigade onto the reverse side of the breastworks. It was hopeless. In short order, Kershaw’s division overran the men in the 156th and 176th New York Regiments. The improvised position, in the words of Union Captain John W. DeForest of Emory’s staff, “had been changed from a fortress to a slaughter pen.” Emory gave the order to fall back.

As Emory’s troops retreated, their comrades in the VI Corps, acting as the Union reserve, covered the retreat as best they could. At Belle Grove, Crook and his staff attempted to stem the tide of disaster while company clerks flung papers and maps from Sheridan’s headquarters into hastily loaded wagons. A hastily organized counterattack failed to check the Confederate advance. At 7:30 am, the almost incredulous Southerners overran the Federal camp at Belle Grove and immediately began looting the now-abandoned tents. “What a sight,” recalled Confederate Captain D.A. Dickert. “Here came stragglers, who looked like half the army, laden with every imaginable kind of plunder—some with an eye to comfort had loaded themselves with new tent cloths, nice blankets, overcoats, or pants, while others had invaded the sutlers’ tents and were fairly laden down with such articles as they could find. I saw one man with a stack of wool hats on his head, one pressed in the other, until it reached more than an arm’s length above his head.”

While his jubilant, if exhausted, soldiers scooped up the spoils of war, Jubal Early rode north along the Valley Turnpike, his face “radiant with joy,” in the words of one staff officer. In mock Napoleonic grandeur, he intoned: “Ah, the sun of Middletown! The sun of Middletown!” Just south of the crossroads village, he encountered Gordon, who was attempting to reorganize his men and send them after the retreating Federals. “Well, Gordon,” Early greeted him, “this is glory enough for one day.” Gordon shook his head. “It is very well so far, general,” he quoted himself in his memoirs, written three decades after the battle, “but we have one more blow to strike, and then there will not be an organized company of infantry in Sheridan’s army.” “No use in that,” Early assured Gordon. “They will all go directly.” “That is the Sixth Corps, general,” Gordon replied. “It will not go unless we drive it from the field.” “Yes, it will go, too, directly.” At those words, Gordon recalled, “My heart went into my boots.”

Early explained his decision after the war in his own memoirs. “It was now apparent,” he wrote, “that it would not do to press my troops further. They had been up all night and were much jaded. In passing over rough ground to attack the enemy in the early morning, their own ranks had been much disordered, and the men scattered, and it had required much time to reform them.” Having driven off an army nearly twice his size, capturing 1,300 prisoners and 18 artillery pieces in the process, Early seemed content to hold the ground and consolidate his gains. He may have overestimated his men’s weariness; he certainly underestimated the will of his chief adversary.

“Give ’em Hell, God Damn ‘em!”

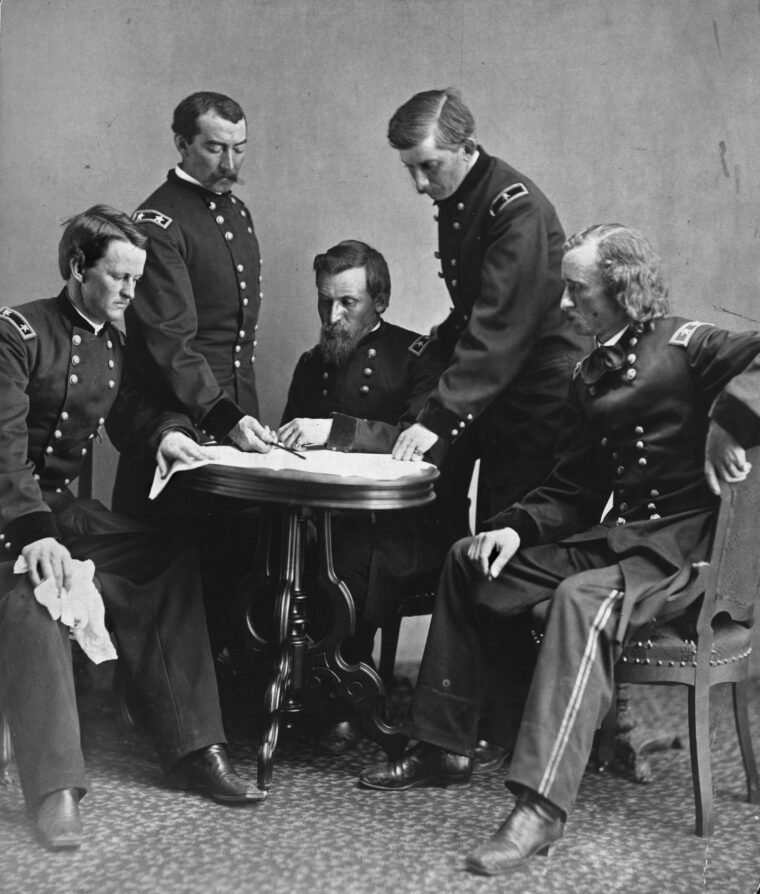

It was nearly 9 am before the general and his traveling companions—Lt. Col. James Forsyth, Major George “Sandy” Forsyth (no relation), Captain Joseph O’Keefe, and two Washington-based engineers—had left the Logan residence and set off southward. As they departed, Sheridan noticed, many of Winchester’s female population “kept shaking their skirts at us and were otherwise markedly insolent in their demeanor.” He put it down to unregenerate Rebel sentiment. At Mill Creek, just outside town, Sheridan picked up his prearranged escort, 300 troopers from the 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry. By now the noise from the south was an unceasing roar. Sheridan dismounted and put his head to the ground, Indian-style, to listen. There was no longer the shadow of a doubt in his mind—a major battle was under way at Cedar Creek. Looking “somewhat disconcerted,” in Sandy Forsyth’s view, Sheridan mounted up and the column continued southward. Coming over the rise of a hill, they suddenly confronted “the appalling spectacle of a panic-stricken army—hundreds of slightly wounded men, throngs of others unhurt but utterly demoralized, and baggage-wagons by the score, all pressing to the rear in hopeless confusion.”

From a handful of frazzled officers, Sheridan heard what his eyes had already told him: the army had been surprised and routed. It was scarcely to be believed. Sheridan had seen another routed Union army—or half a routed army—13 months earlier at Chickamauga, but at least then he had been present and in the midst of the action. Somehow, while he was still sleeping, a Confederate force had fallen on his own army at Cedar Creek. His first thought was to regroup outside Winchester for a last-ditch stand—he knew the ground well. But as he moved on, walking Rienzi at a measured pace while he mulled over what to do, he decided instead to continue to the front. (The example of his unfortunate commander at Chickamauga, William Rosecrans, may be been in the back of Sheridan’s mind. Rosecrans had ridden away from the battlefield that day while Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas rallied the remainder of the army to hold fast at Snodgrass Hill. Thomas had won lasting fame; Rosecrans had been fired a few weeks later.) Whatever the inspiration, Sheridan’s decision was a momentous one, for both himself and the Union fortunes of war. All his life he had responded aggressively to any challenge, a small man who had learned to strike back hard at the first sign of danger. Remaining behind in Winchester, rounding up fugitives for a defense line as Rosecrans had done at Chickamauga, was not in Sheridan’s basic nature. Punched in the nose, the brawling little alley fighter gathered himself to punch back hard.

Leaving James Forsyth and a majority of his cavalry escort to act as a glorified straggler line below Winchester, Sheridan spurred Rienzi toward the ragged sound of battle. Sandy Forsyth, O’Keefe, and 20 Pennsylvania troopers rode behind him, along with a little orderly who carried the general’s distinctive swallow-tailed flag—red star on white background, white star on red. Still wearing his formal dress uniform from his visit to Washington, Sheridan wore a regulation kepi with two crossed silver swords inside a gold wreath instead of his familiar black porkpie hat.

The company was still 10 miles north of Cedar Creek. Through a brilliant Indian-summer morning they rode, white dust from the turnpike powdering their dark-blue uniforms. Sheridan, 50 yards in the lead, passed long files of walking wounded and an equal number of soldiers who were wounded only in their pride. Occasionally taking to the fields to avoid a tangle of wagons on the roadway, he waved his felt campaign cap at the knots of men huddled around improvised campfires heating coffee. “Come back, boys!” he shouted. “Give ’em hell, God damn ‘em! We’ll make coffee out of Cedar Creek tonight! Face the other way! We’re going to lick those fellows out of their boots!” One infantry colonel, unstrung by the rout, shouted back, “The army’s whipped!” and continued running. “You are,” Sheridan scoffed, “but the army isn’t.” He rode on.

As Sheridan Reorganizes, Early Dallies

The closer they came to the front, the more unmistakable were the signs of defeat. At Newton the turnpike was so jammed with fleeing supply wagons, artillery caissons and overburdened ambulances that the party again was forced to leave the road and take to the fields. A young major on Crook’s staff, future president William McKinley, caught sight of the general’s headquarters flag and rode ahead to spread the word that Sheridan had returned. Swinging back onto the turnpike below Newtown, Sheridan spotted the first heartening sight he had encountered since leaving Winchester. Three-quarters of a mile west of the pike an organized body of troops, which proved to be Ricketts’s and Wheaton’s VI Corps divisions, was standing fast in line of battle. Not everyone, it appeared, had abandoned the field.

Spurring Rienzi onward, Sheridan crossed the road and soon caught sight of another group of soldiers, Getty’s VI Corps division, which was acting as the broken army’s rear guard three miles north of Cedar Creek. Brig. Gen. Alfred Torbert was the first general officer to greet Sheridan on his arrival. “My God, I’m glad you’ve come!” he shouted over the din. The two officers leaped their horses over a hastily built barricade of fence rails and wheeled to face what remained of the army. “Men, by God, we’ll whip them yet!” Sheridan roared. “We’ll sleep in our old tents tonight!” At Sheridan’s words, the formerly downcast soldiers shouted, cheered, and stamped their feet in approval. Major Hazard Stevens noticed the sudden change. “Instantly,” he wrote, “hope and confidence returned at a bound. Now we all burned to attack the enemy, to drive him back, to retrieve our honor and sleep in our old camps that night. And every man knew that Sheridan would do it.”

A flourish of regimental flags welcomed Sheridan back to the field. The ad hoc color-bearers were mainly officers from Crook’s VIII Corps, among whom Sheridan recognized Colonel (and future president) Rutherford B. Hayes. Riding on, Sheridan located his erstwhile corps commanders Wright, Crook, and Emory, who were standing together a little shamefacedly atop a debris-strewn hill. Hurriedly dismounting, Sheridan handed Rienzi’s reins to an orderly and impulsively threw his arms around the taller Crook in a comradely embrace. “What are you doing back here?” he asked. Crook shrugged. Wright, in whose charge Sheridan had left the army four days earlier, looked on silently, his chin still dripping blood from a Rebel bullet. “Well, we’ve done the best we could,” Wright offered. “That’s all right,” Sheridan said, somewhat surprisingly, given the morning’s events. Emory broke the fraternal mood; his troops, he said, were prepared to cover the retreat. “Retreat hell!” Sheridan stormed. “We’ll be back in our camps tonight.”

Hastily taking stock of the situation, Sheridan brought up Wright’s and Emory’s other divisions, anchoring them to Getty’s steadfast line and sending Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer’s cavalry division over to the Union right. All this took time. It was nearly noon before the long blue line was formed again. Meanwhile, Sandy Forsyth suggested that Sheridan ride the length of the front to show himself to the remaining troops. Sheridan, his blood boiling, needed little prodding. He galloped along, swinging his hat in his right hand to give soldiers a glimpse of his familiar bullet-shaped head. A mighty cheer went up. To Major Aldace Walker of the 8th Vermont it seemed that “no more doubt or chance of doubt existed; we were safe, perfectly and unconditionally safe, and every man knew it.”

Sheridan’s return electrified his troops, but nothing was done immediately to reverse the morning’s events. By now, Early had had the better part of six hours to renew his attack, entrench his position, or withdraw from the field with his hard-won booty. Instead, as Gordon had feared, the Confederate commander dithered away precious hours, sending out tentative, unsupported probes that were easily beaten back by the Union defenders. “We halted, we hesitated, we dallied,” Gordon remembered, “firing a few shots here, attacking with a brigade or a division there, and before such feeble assaults the superb Union corps retired at intervals and by short stages.” Even as long as 30 years later, Gordon could not conceal his bitterness and anger at Early’s delay. “We waited,” Gordon fumed, “waited for weary hours. Waited till the routed men in blue found that no foe was pursuing them and until they had time to recover their normal composure and courage; waited till Confederate officers lost hopes and the fires had gone out in the hearts of the privates.” Early himself admitted as much. “The Yankees got whipped,” he said, “and we got scared.”

Sounding the Union Charge

The afternoon wore on, an eerie quiet blanketing the battlefield. Sheridan, having calmed down considerably since his ride to the front, lounged on the grass at his hilltop headquarters, elbow propped casually on the ground, waiting for the rest of his army to straggle back into camp. Aides kept dashing up, urging him to retake the offensive, but Sheridan put them off with a clipped “Not yet.” It was nearly 4 pm when he finally judged the time ripe to counterattack. Orders went out to the various corps commanders; Emory, on the right, was to lead the charge, swinging left as he advanced to drive the enemy toward the Valley Turnpike. Wright’s corps, in the center, would move ahead more deliberately, giving Emory time to make his turning movement. Crook’s corps, still disheveled from its morning beating, was to hold the Union left, blocking the turnpike and serving as a backstop to the giant Union pivot.

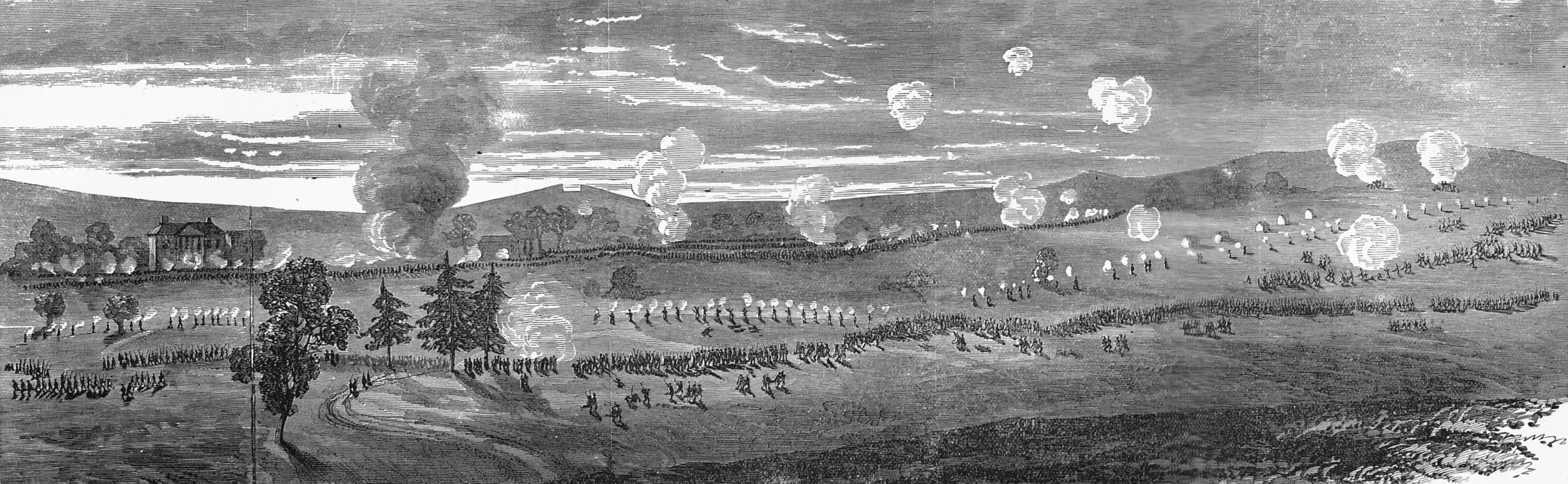

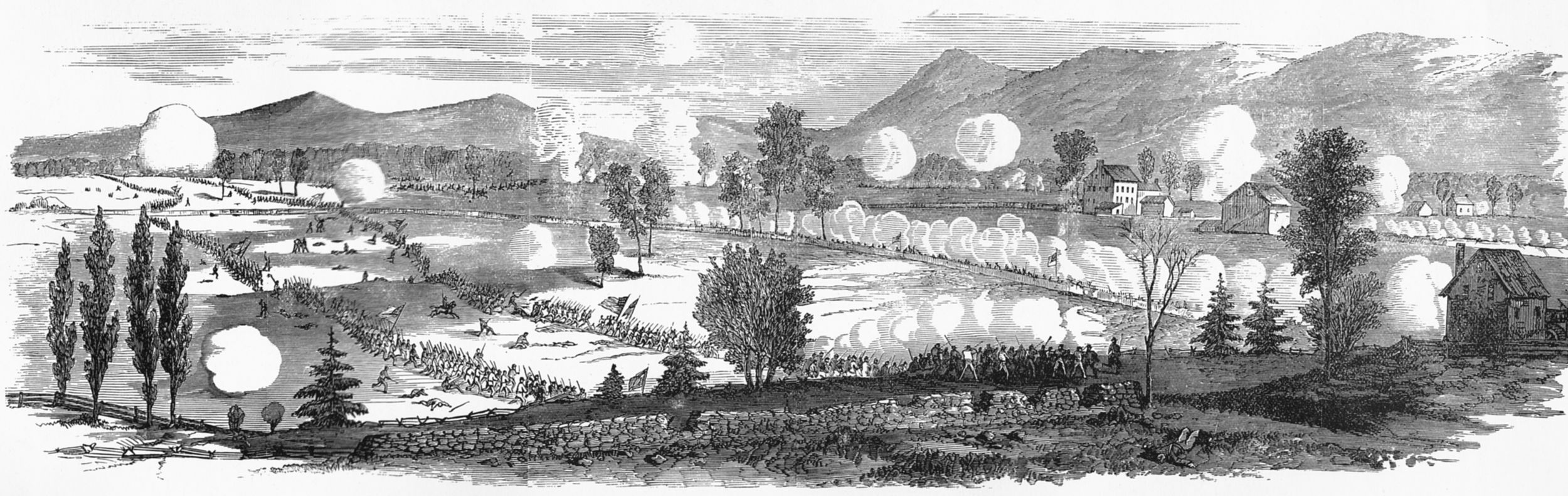

Two hundred Northern buglers sounded the charge, and the men of the XIX Corps moved out on the right, aiming for the Confederate left flank anchored on two small hills a half mile away. This flank, held by Gordon’s own division, was perilously strung out, with a good 30 feet between each man. Worse yet, there was a gap between his westernmost brigade and the rest of the army, a gap that “would prove a veritable deathtrap if left open many minutes longer,” he warned Early. Sheridan, his view obscured by trees and distance, had no way of knowing this; he simply sent his army forward and waited, like Napoleon, for events to unfold naturally and inevitably.

A jagged orange blast of gunfire erupted along the Confederate line as Sheridan’s army came into view. “A deep roar broke upon the summer stillness,” recalled Dr. Harris Beecher of the 114th New York, “in which the very skies seemed to quake. Then an overpowering torrent of shells, grape and bullets tore through the devoted ranks, with murderous effect, followed by a stifling, acrid cloud of smoke, which hovered over the assailants and dimmed the horrid sight.” On the right, Emory’s men withstood the murderous volley and, fighting blindly in a jungle-like thicket of trees and vines, seized the hills on the enemy left. Sheridan, now riding a replacement horse, Breckinridge, in place of the exhausted Rienzi, joined his men on the crest and told them to wait for Custer’s cavalry to lead the next wave of the attack. “This is all right! This is all right!” he encouraged. Custer arrived a few moments later, his yellow-blond hair waving in the breeze, and impulsively threw his arms around Sheridan’s neck. The general, a little irritated, disengaged himself from the embrace, then resumed inspecting the new lines. “Lie down right where you are,” he told the men, “and wait until you see General Custer come down over those hills, and then by God, I want you to push the Rebels!”

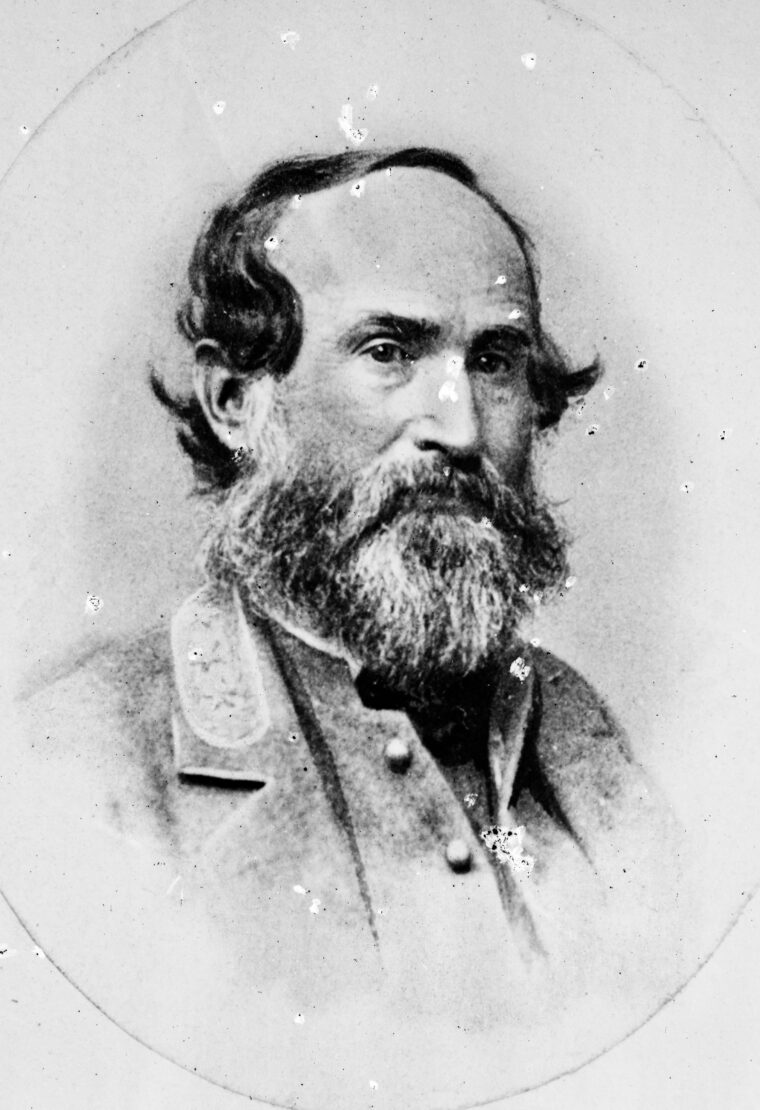

The attack on the Confederate center had not gone as well as the one of the left. Kershaw’s and Ramseur’s divisions, sheltered behind improvised stone walls, stood their ground. Rifle fire was deadly and continuous along the lines. Neither side could move forward or take the chance of withdrawing at such close range. A furious deadlock held sway over the field. Then, at 4:30, the gray dam broke as Custer’s troopers swung left behind the Confederate flank and drove the panicked foot soldiers before them. Gordon, attempting to rally the men, looked on in dismay. “Regiment after regiment, brigade after brigade, in rapid succession was crushed,” he wrote. “And like hard clods of clay under a pelting rain, the superb commands crumbled to pieces.” In the center of the disintegrating army, Ramseur attempted to make a final stand around a dammed millpond, but went down with a mortal wound to the chest, still wearing the white flower he had pinned to his uniform earlier that morning in honor of the newborn daughter he would never see. With astonishing swiftness, the entire Confederate Army splashed back across Cedar Creek and withdrew into the shadows of Fisher’s Hill.

A Personal Victory for Phil Sheridan

Back at Belle Grove, exultant Union officers built a bonfire in front of the mansion and snake-danced around it in the growing dark. Captured or recaptured artillery and wagons rattled ceaselessly into the yard, while long files of stretcher bearers trudged by the firelight. Sheridan paced back and forth, exchanging handshakes and backslaps with his delighted subordinates. Custer reined up on his horse, dismounted, and grabbed the commanding general yet again, whirling him around and shouting, “By God, Phil, we’ve cleaned them out of their guns and got ours back!” General Emory, watching the celebration, murmured to his aides, “This young man [Sheridan], only about thirty years old, has made a great name for himself today.”

So he had. The victory at Cedar Creek was a personal as well as a national triumph, and Sheridan had virtually willed it into being. From the lonely moment on the Winchester turnpike when he deliberately chose to return to the battlefield, he had accomplished something of a military miracle, rallying a beaten army, reinvigorating it with his own tornadic personality, and sending it forward to an 11th-hour victory, the likes of which had seldom been seen in American history. At his own headquarters in Petersburg, Union commander in chief Ulysses S. Grant said of his longtime protégé, “Turning what bid fair to be a disaster into glorious triumph stamps Sheridan, what I have always thought him, one of the ablest generals.”

Back at New Market, 35 miles south of Cedar Creek, Sheridan’s thrice-beaten adversary paused to make his own report to his commanding officer. “We had within our grasp a glorious victory,” Early telegraphed Robert E. Lee, “and lost it by the uncontrollable propensity of our men for plunder, in the first place, and the subsequent panic among those who had kept their places, which was without sufficient cause, for I believe the enemy had only made the movement against us as a demonstration, hoping to protect his stores, etc., at Winchester, and that the rout of our troops was a surprise to him.” Once again, Early had completely misjudged Sheridan, who had launched a full-scale counterattack against him—not a “demonstration.”

In the end, a Confederate veteran of the battle made perhaps the best summation of the remarkable turn of events. “The fact was generally conceded among the troops,” the veteran wrote, “that the unfortunate result of the engagement was due to two mistakes; one was that General Sheridan was not at his headquarters with his army and the other was that General Early was present with his.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments