By Allan T. Duffin

On Saturday, May 5, 1945, three days before the end of World War II in Europe and just three months before the Japanese surrendered, spinning shards of metal ripped into the tall pine trees, burrowing holes into bark and tearing needles from branches outside the tiny logging community of Bly, Oregon. The nerve-shattering echo of an exploding bomb rolled across the mountain landscape. When it was over, a lone figure—Archie Mitchell, a young, bespectacled clergyman—stood over six dead bodies strewn across the scorched earth. One of the victims was Elsie Mitchell, the minister’s pregnant wife. The rest were children barely into their teens.

Mitchell, pastor of the Christian Missionary Alliance Church, had invited students from his Sunday school classes to a picnic on Gearhart Mountain in the Fremont National Forest. Everyone piled into the Mitchells’ automobile and rode to the secluded area, where Mitchell dropped off his wife and the other picnickers as he parked the car. Suddenly Elsie called out to him. She and the children had found something on the ground. “Don’t touch that!” shouted Mitchell. He was too late. A sudden explosion rent the air.

Hurrying over, a horrified Mitchell stood over the mangled body of his dead wife. Hot shrapnel was still burning on her body. Four of the children—Jay Gifford, Eddie Engen, Dick Patzke, and Sherman Shoemaker—lay dead alongside her. Joan Patzke, 13 years old, initially survived the explosion but succumbed to her injuries shortly afterward.

Forestry workers were running a grader nearby when the force of the explosion blew one of them off the equipment. Another dashed to the nearby telephone office, where Cora Conner was running the town’s two-line exchange that day. “He had me place a call to the naval base in nearby Lakeview, the closest military installation to our town,” recalls Conner. “He told them that there had been an explosion and people had been killed.”

Six Deaths From an “Unannounced Cause”

Within 45 minutes, a government vehicle roared to a stop in front of the telephone shack. A military intelligence officer scrambled out of the car and joined Conner inside. “He warned me not to say anything,” Conner says. “I was not to accept any calls except military ones, nor was I allowed to send out any information.” The rest of the day proved difficult, as Conner struggled with lumber companies and angry locals who had been stripped of their phone privileges without explanation. Angry citizens congregated outside the telephone office, banging on the windows and doors. A frightened Conner handled it as best she could. Ironically, the 16-year-old Conner had narrowly missed becoming another victim of the mishap. “Dick and Joan Patzke were in our kitchen that morning and invited my sister and me to join them on the picnic,” Conner recalls. “But Saturday was a workday in our house, so we didn’t go.”

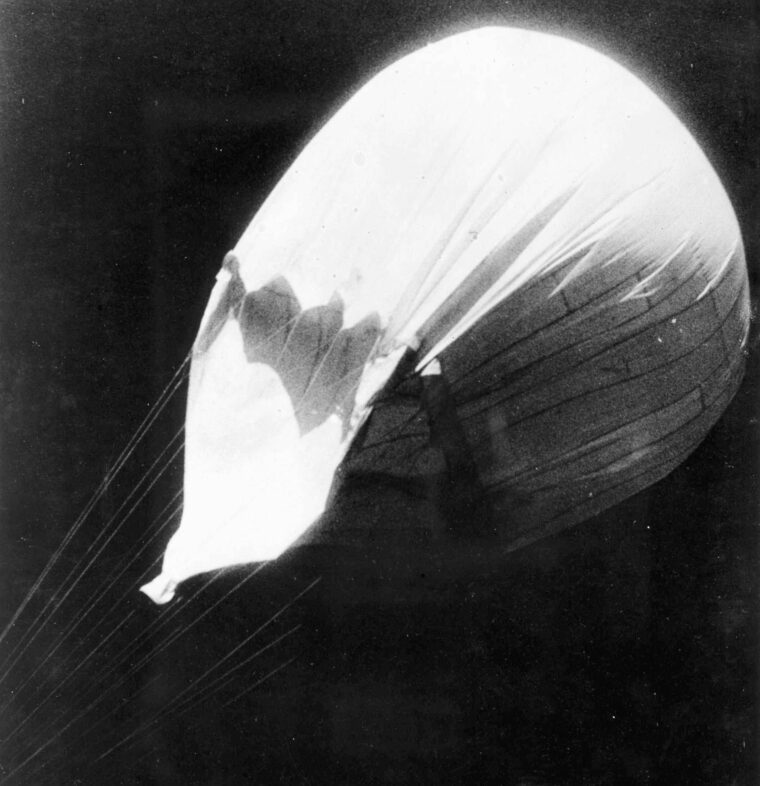

Back on the mountain, Army intelligence officers joined the local sheriff at the accident site. The bodies of the victims were grouped within a 10-foot radius of the explosion, which had churned up the forest floor. At the center of the impact zone, lying on a snow pile six inches deep, were the rusting remains of a bomb. A huge paper balloon, deflated and pockmarked with mildew, lay nearby.

The U.S. government immediately shrouded the event in secrecy, labeling the six deaths as occurring from an “unannounced cause.” But in the close-knit atmosphere of Bly, 25 miles north of the California state line, many of the locals had already learned the truth: Elsie Mitchell and the five children were victims of an enemy balloon bomb, held aloft by a gigantic hydrogen-filled sphere and whisked from Japan to the western seaboard of the United States. The contraption had alighted on Gearhart Mountain, where it lay in wait until the fateful day when it found its victims—the only deaths from enemy attack within the continental United States during World War II.

The Japanese high command launched balloon bombs against the United States for a period of six months, from November 1944 through the spring of 1945. In an ironic twist, the Japanese had canceled the program just several weeks prior to the incident in Bly, citing the program’s apparent ineffectiveness. A five-month media blackout ordered by the U.S. government helped disguise the fact that several hundred Japanese balloon bombs had reached the West Coast. Woodsmen in Spokane, Washington, stumbled across two fallen bombs on the ground and, according to reports, “fiddled” with the devices, which failed to detonate. Elsewhere, a farmer noticed one of the balloons drifting in the sky above, then watched as it plummeted to the ground and wedged itself against a barbed wire fence. He was able to secure the device for investigation by the FBI and military authorities. Week after week, the public reported more and more sightings of the mysterious airborne devices. Balloons fell into rivers, tumbled onto forest roads, and interrupted electric service when they dropped onto power lines. Military pilots engaged balloons in midair and shot them down.

The Japanese Balloon Project: Avenging the Doolittle Raid

For Americans living near the coastline, the threat of a Japanese invasion by air or sea was nothing new. In September 1942, a Japanese submarine surfaced off the Oregon coast and launched a small airplane that dropped a 165-pound incendiary bomb over the Siskiyou National Forest. Authorities quickly contained the resulting fire, which was minor and had little effect. Further exploring their long-range options, the Japanese also planned to riddle the American coastline with submarine-fired rocket volleys. But as the war continued and the Allies marched ever closer to Tokyo, the Japanese high command altered its plans. The balloon bomb, though seemingly a passive weapon, provided the Japanese with an effective method of bringing the war to American shores without expending enormous amounts of manpower and materiel. When detonated, the bombs might trigger massive forest fires in the northwestern United States that would divert manpower from the war effort and knock the lumber industry back on its heels. Moreover, the potential devastation would hammer away at American morale.

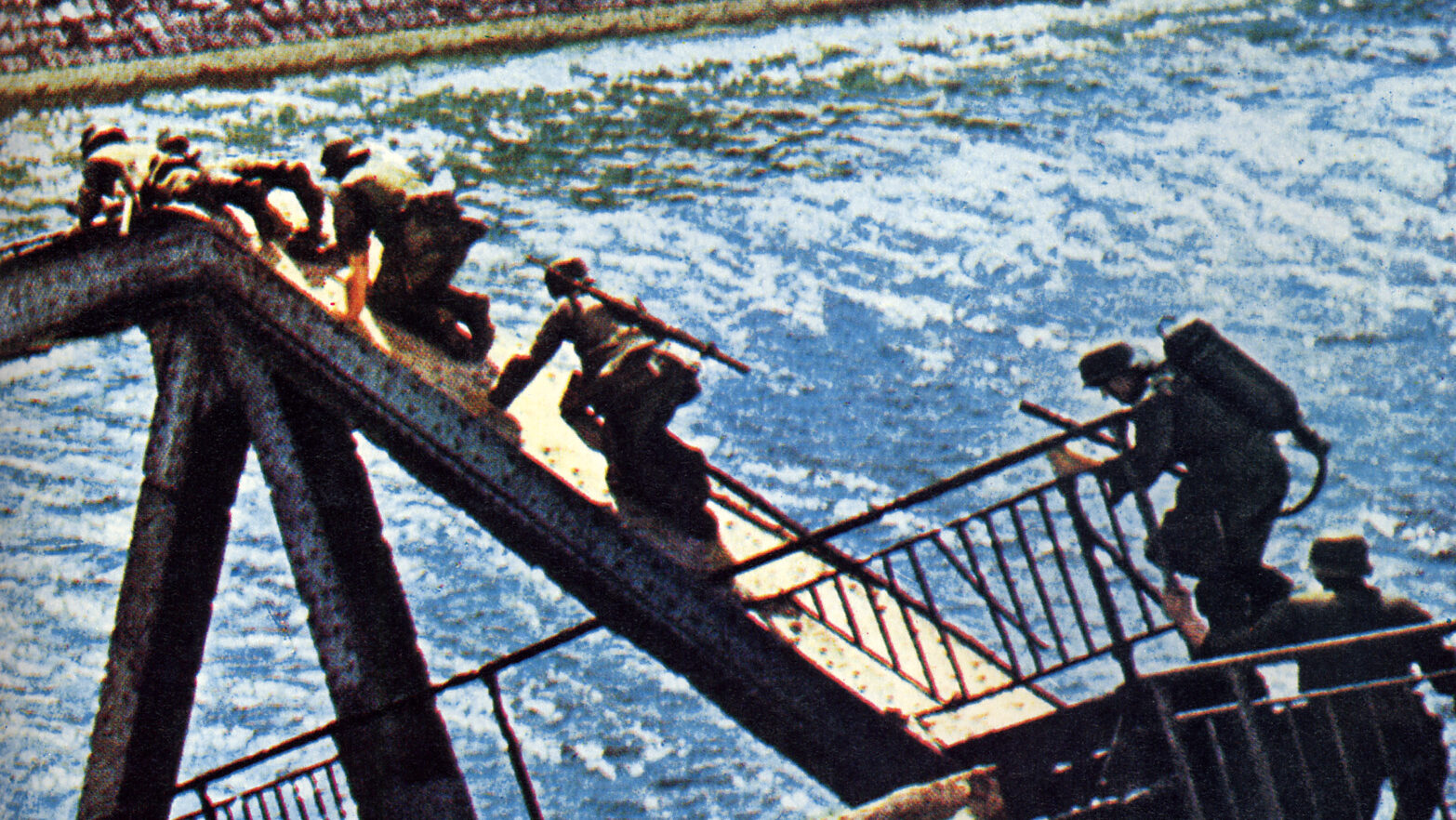

The Japanese balloon project was revenge for an altogether different morale-smashing mission. In April 1942, four months after the Pearl Harbor attack, Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle and 16 B-25 medium bombers roared off the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet to pummel targets in and around Tokyo. The Doolittle Raid, although limited in destruction, was an effective psychological ploy, proving that American forces had the capability to strike the Japanese homeland. In retaliation, the Japanese high command injected new life into its previously dormant balloon project, which had begun in the early 1930s but had been relegated to the back burner as other wartime priorities took hold.

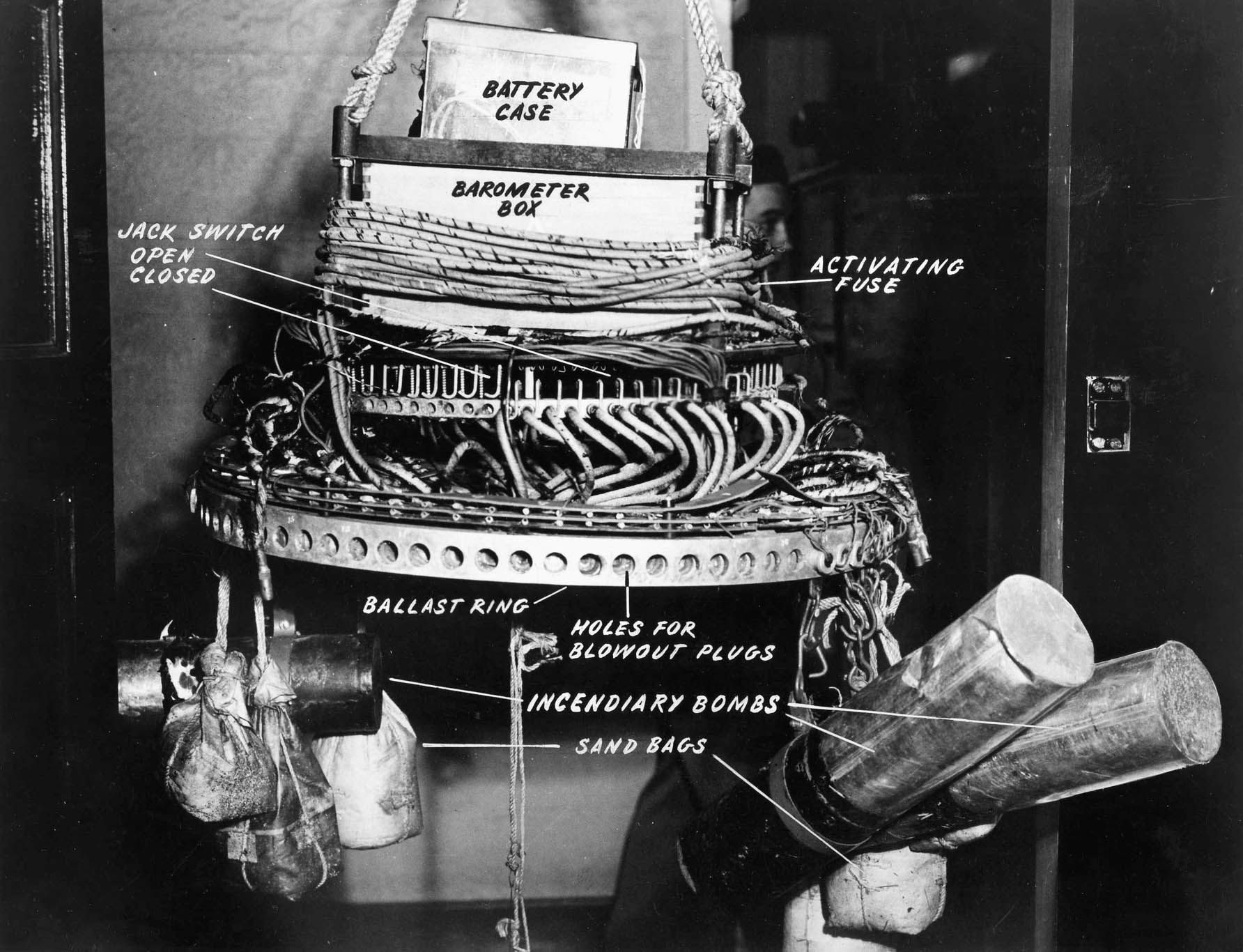

Two years passed before the Japanese launched the first operational balloon bomb across the Pacific. The designers planned to have the balloons drop their ordnance via timed fuses, but an important question had to be answered: how would the device maintain altitude for 70 hours as it traversed 6,000 miles of ocean? Some sort of altimeter was needed to respond to changes in air pressure as the balloon sailed along its path. A gas-discharge valve and ballast-dropping system were added to the design, allowing the balloon to self-correct any drops in altitude. The jet stream, an atmospheric phenomenon just beginning to be understood, would do the rest, carrying the balloon from the Japanese mainland all the way to North America.

10,000 “Fugo” Balloon Bombs

The Japanese set a production goal of 10,000 balloons. Due to wartime shortages, only 300 balloons of rubberized silk were crafted; the rest were made of paper. School children were drafted to paste together balloons in seven factories around Tokyo. When pumped full of hydrogen, the spheres grew to 33 feet in diameter. Each balloon was wrapped in a cloth band from which hung a set of 50-foot shroud lines to carry its ordnance and instruments. A typical balloon was equipped with five bombs, including a 33-pound antipersonnel device and several types of incendiaries. To launch the weapons en masse, the Japanese selected three sites on the island of Honshu. Each launch procedure required 30 personnel and took half an hour to complete. With good weather, several hundred balloons could be launched each day.

After several hundred tests, the Japanese released the first balloon bomb, named fugo, or “wind-ship weapon,” on November 3, 1944. Additional launches followed in quick succession. A large number of the balloons that successfully reached North America failed to release their bomb loads when they arrived. By the summer of 1945, nearly 300 fallen balloons would be found, strewn across 27 different states. Balloons were reported over an area stretching from the Alaskan island of Attu to Michigan—all the way to northern Mexico. The American media reported on many of the earliest recoveries, but in January 1945 the government’s Office of Censorship, hoping to convince the Japanese that their program was failing, ordered a publicity blackout. That same day, a balloon bomb exploded in Medford, Oregon, digging a shallow crater and shooting flames 20 feet into the air.

At first, American authorities surmised that the balloons were originating in German POW camps or Japanese internment camps within the United States. Other experts thought the devices were weather or barrage balloons that had drifted off course. As more of the balloons were recovered across North America, however, the military realized that they were dealing with a new type of enemy weapon. With a little scientific detective work, the government pinpointed the geographical origin of the sand used in the weapons’ ballast bags. American B-29 bombers were dispatched to Honshu, Japan, where they destroyed several plants involved in the production of hydrogen for the balloons, effectively crippling the fugo project. Back in the United States, military officials quickly coordinated search efforts with forest rangers and law enforcement officials. Airborne coastal defense, less of a priority as the war neared its end, underwent a brief resurgence as the U.S. Army’s Project Sunset coordinated radar and aircraft surveillance around the clock. Over 2,000 military personnel participated in the overall effort to track, recover, and study the balloon bombs.

Warning the Public of the Threat of Balloon Bombs

On May 10, 1945, five days after the bombing of Bly, more than 450 people attended a mass funeral for the victims. Due to the size of the crowd, the service was held at the Klamath Temple in Klamath Falls, 50 miles southwest of Bly. Boy Scouts served as pallbearers, as the male victims had all been members of the local troop. To help avoid similar tragedies, the government lifted the media blackout. In late May 1945, the headquarters of Western Defense Command, based at the Presidio in San Francisco, issued a cautious message entitled “Japanese Balloon Information Bulletin No. 1.” In an effort to avoid a media frenzy and quell public paranoia, the document was to be read aloud to small gatherings “such as school children assembled in groups, preferably not more than 50 in a group and Boy Scout troops.” The bulletin warned that many hundreds of Japanese balloons were reaching American and Canadian airspace. If anyone came upon such a balloon bomb on the ground, the document instructed him to keep at least 100 yards away from the device and inform the local police or sheriff. “Let us all shoulder this very minor war load,” read the bulletin, “in such a way that our fighting soldiers at the front will be proud of us.”

In Japan, radio broadcasts trumpeted the success of the balloon bomb program, claiming that the devices had triggered major fires and caused 500 American casualties. The propaganda broadcasts promised that Japanese soldiers would invade the United States by the millions, all carried to the enemy coast by massive balloons. In reality, the Japanese high command had heard little about the balloon bombs’ effects on the United States before abruptly canceling the program in April 1945. Of the 9,000 balloons launched by the Japanese, experts estimated that perhaps 900 reached North America.

Memorializing the Victims of the Balloon Bombs

The accident site in Bly became a tragic landmark for the local community. In 1950, the Weyerhaeuser lumber company asked Robert Anderson, a local stonemason and Navy veteran, to create a monument to the victims of the balloon bomb. A newspaper account noted that “the wooded spot where tall pines show scars left by bomb fragments has been set aside by Weyerhaeuser Timber Company as Mitchell Recreation area, named in honor of the Rev. Archie Mitchell, sole survivor of the war tragedy. The location is on a Weyerhaeuser tree farm.” Today the land is supervised by the Forest Service.

Although the town of Bly soldiered on, the shock of the balloon bomb incident reverberated for decades afterward. Some 40 years after the deaths on Gearhart Mountain, John Takeshita, a former resident of the wartime relocation camp at Tule Lake, California, met a Japanese woman who as a young student during World War II had pieced together paper balloons in Tokyo. Takeshita, intrigued, talked to the woman and many of her former classmates, all unwitting participants in the balloon project during the war, and shared the story of the tragedy that had occurred in Bly. In 1985, the Japanese women crafted 1,000 paper cranes, symbols of peace, and sent them to the family members of those who were killed by the balloon bomb. Later, handmade dolls and handwritten letters arrived from Japan, each one a heartfelt apology to the people of Bly.

In May 1995, 50 years after the incident, nearly 500 people convened in the Mitchell Recreation Area for a rededication of the accident site. “It was really something,” remembered Ed Patzke, brother to two of the victims. “Hard to believe it could be put on by a little place like this. They had 10 big school buses to transport people to the site. There were several different speakers. They were playing taps and the bagpipes played ‘Amazing Grace.’ Near the end they had a flyover by the fighter jets from the Air National Guard unit at Kingsley Field. Most of the town was there. It was very effective.” John Takeshita purchased cherry trees to plant at the accident site, at Reverend Mitchell’s old church in Bly, and at a school in Japan that had supplied students for the balloon project.

On the day of the rededication, Cora Conner was finally able to come to terms with what had happened on Gearhart Mountain half a century earlier. Locked away in the telephone office on the day of the bombing, unable to inform anyone about what had happened, she had been haunted by the incident long after the bodies were cleared away. “I had really, really bad nightmares for years,” she says. “I didn’t realize what was causing them until I met John Takeshita and the Japanese women who visited Bly for the ceremony. One of the girls who had been involved in making the paper for the balloons was the same age I was. I was fortunate to meet her and talk about what had happened. It began to ease the pain, and eventually the nightmares stopped.”

For Archie Mitchell, who lost his wife, unborn child, and five members of his church on that fateful day in 1945, life eventually resumed its course. He remarried and in 1947 moved to Southeast Asia to continue the missionary work that inspired him. Unfortunately, fate would deal him yet another blow. On June 1, 1962, a wire report brought his name back into the news: “Today word came from South Vietnam that three Americans had been kidnapped by Communist guerrillas. One of them is Reverend Archie E. Mitchell, a former pastor at Bly in southeast Oregon.” Mitchell was never heard from again.

The Missing Balloon Bombs of North America

Even today, unrecovered balloon bombs are thought to dot the North American landscape. The bombs are slowly disintegrating with time, but are still potentially lethal. To date, approximately 300 of the aged weapons have been found. As late as 1992, a balloon bomb was recovered in Jackson County, Oregon, about 100 miles west of Bly. Nearby, the Klamath County Museum keeps the history of the incident alive for current and future generations. Todd Kepple, manager of the museum, notes, “It’s safe to say that we’ll always feature an exhibit on Japan’s balloon bomb campaign, including its general failure to inflict the widespread damage that was intended, and the heartache it caused in one tiny Northwest community. Many current residents of southern Oregon are scarcely aware of the history of Japanese balloon bombs, but a handful of local residents are determined to make sure the story is never forgotten.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments