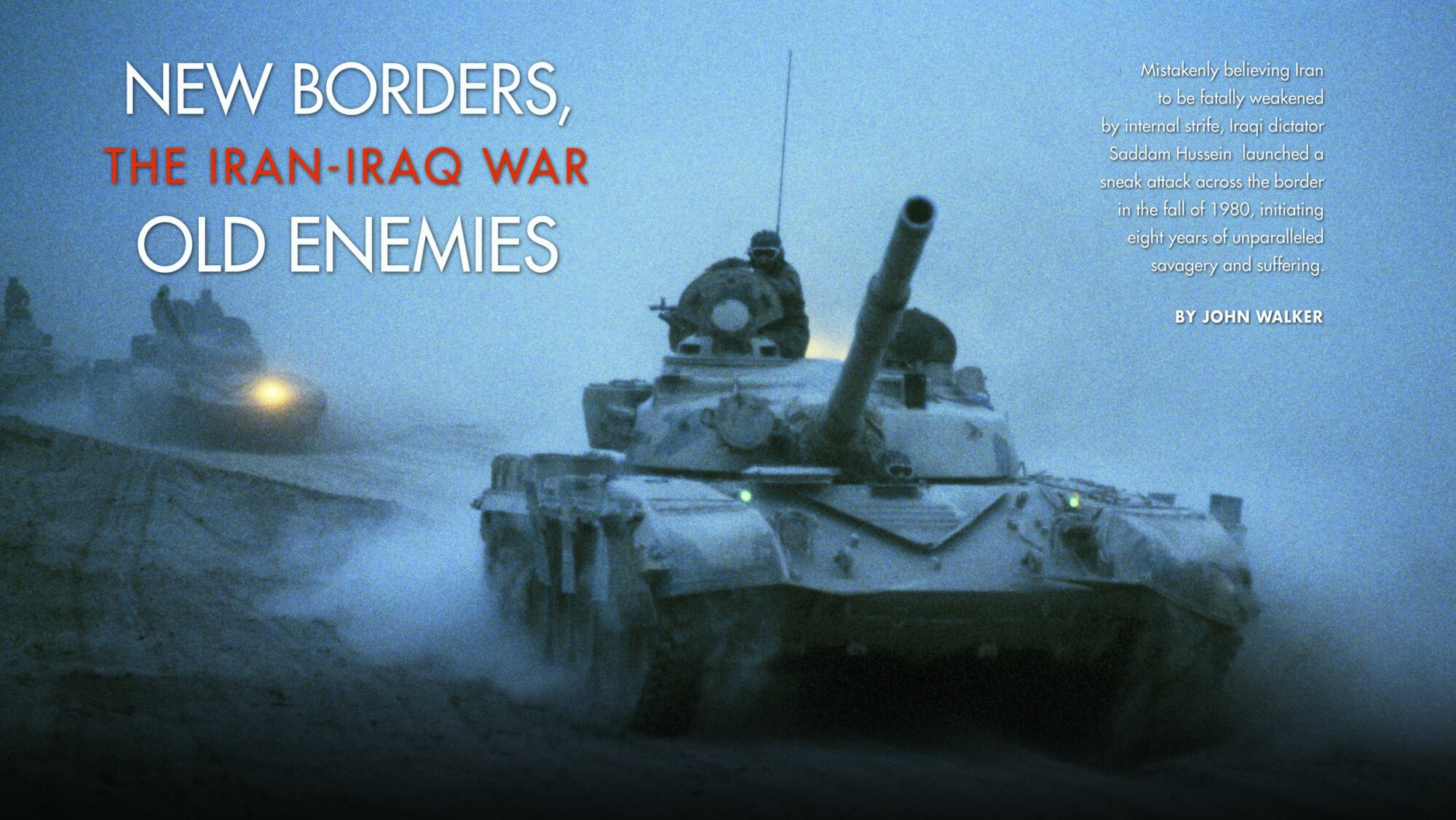

By John Walker

The world awoke to ominous news on September 22, 1980. Iraqi despot Saddam Hussein had launched a massive armored and air attack across the Iraq-Iran border. Believing that his Islamic fundamentalist neighbor to the east had been weakened by the ongoing revolutionary turmoil that in February 1979 had toppled the Shah, Hussein was confident that his forces would win a lightning victory and restore long-disputed territory to Iraqi control. Such a victory, not incidentally, would put Hussein at the forefront of a resurgent Middle Eastern pan-Arabism.

Among the causes of the war—the ruthless ambition of Saddam Hussein; ongoing disputes over control of the strategic Shatt al-Arab waterway, a shipping lane formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that created the southern borders of both countries; the struggle for dominance in the Persian Gulf region—the overriding issue was a centuries-old dispute regarding sovereignty over oil-rich Khuzestan Province in southwestern Iran. Khuzestan was the ancient home of the empire of Elam, an independent, non-Semitic, non-Indo-European-speaking kingdom whose territory spanned almost all of present-day southwestern Iran. Khuzestan had been attacked and occupied many times by various Arab kingdoms of Mesopotamia, the precursors of modern-day Iraq.

A Centuries-Old Rivalry

The rivalry between Mesopotamia and Persia had lasted for centuries. Before the Ottoman Empire, Iraq was part of Persia. This changed when Murad IV annexed Iraq from the weakening Safavids of Persia in 1638, making it the easternmost province of the Ottoman Empire. Border disputes between Persia and the Ottomans persisted. Between 1555 and 1918 Persia and the Ottomans signed 18 different treaties delineating their disputed borders.

The British and other Western powers received a League of Nations mandate after World War I to carve up the remains of the Ottoman Empire and virtually rewrite the map of the Middle East. The Ottomans had backed the losing side, Germany, against their traditional enemies, the Russians. Great Britain took control of Palestine, Iraq, Trans-Jordan, and various Gulf states; France was responsible for Syria and Lebanon. The new map ignored religious, tribal, ethnic, and historical divisions. Borders did not reflect natural frontiers such as rivers and mountains, but rather demarcations on a map drawn in a European conference room. Of all the new nations created with the potential for ethnic-religious strife, Iraq was the worst, a combustible mix of mutually antagonistic peoples—Shiite Muslims, Sunni Muslims, and Kurds—each of which considered itself separate and sovereign.

Growing Rivalry With Iran

The modern nation-state of Iraq was granted independence in 1932 and immediately spiraled into ethnic and religious turmoil. Iraq was a rarity in the region, a nation where the Sunni minority ruled over the Shiite majority. In 1969, Iraq’s Ba’ath Party mounted a successful coup under the leadership of General Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr and renewed its claim to full control of the Shatt al-Arab waterway. This led Iran to denounce the 1937 treaty dividing control of the waterway between the two nations. On April 22, 1969, an Iranian ship entered the Shatt with a military escort and refused to pay tolls to Iraq. Relations between Iran and Iraq deteriorated over the next two and half years.

On November 30, 1971, the day before the British withdrew from the Gulf for good, Iran seized three strategic islands in the lower Gulf—Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs—owned by the United Arab Emirates. Their seizure led Iraq to sever diplomatic relations with Iran. Scattered border clashes occurred in 1972, after which Iraq expelled some 72,000 Iranians from Iraq. A new series of border incidents occurred in February 1974. Iraq, its military readiness far inferior to that of Iran, was compelled to ask for a compromise, which took the form of the 1975 Algiers Accord. Under its terms, Iran conceded territory in the Qasr e-Shirin area and agreed to halt arms shipments to the Kurds in return for concessions in the Shatt that again designated the middle of the waterway as the international border.

“Totally Iraqi and Totally Arab”

The Iran-Iraq rivalry was profoundly altered by the Islamic Revolution that toppled the Shah in February of 1979, ending 2,500 years of monarchy. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s sudden rise to power created a regime in Iran that was far more of a threat to Iraq than the Shah had ever been. The revolution cut Iran off from the United States and the West. The 444-day U.S. Embassy hostage crisis began on November 4, 1979, and a brutal power struggle broke out between religious revolutionaries under Khomeini and radical Marxist movements that had initially supported the revolution. The internal disarray made Khomeini seem far more vulnerable than he really was, and led Saddam Hussein to believe that the time was ripe to transform Iraq into the dominant power in the Gulf.

On September 17, 1980, Hussein abrogated the 1975 Algiers Accord and declared the Shatt al-Arab “totally Iraqi and totally Arab.” Heavy fighting broke out along the waterway, and Iranian President Abolhassan Bani-Sadr decreed a general mobilization. Convinced that his antagonist had been severely weakened by the purges of its regular forces and was preoccupied with suppressing grave internal threats, Hussein launched an invasion two days later. Six Iraqi army divisions advanced into Iran on three fronts along a 435-mile-broad arc in an initially successful surprise attack. In the north, an Iraqi mechanized division overran the border garrison at Qasr e-Shirin in Bakhtaran Province and pushed on, advancing 25 miles eastward to the base of the Zagros Mountains. Iraq’s forces spent several days reaching the villages along the main route to Tehran; many villages were destroyed and their inhabitants expelled. On the central front, Iraqi forces captured Mehran, on the western edge of the Zagros chain in Ilam Province, an important position on the major north-south highway close to the border.

Unexpected Fierce Resistance

The main thrust came in the south, where five armored and mechanized divisions invaded Khuzestan Province on two axes. One easily crossed the lightly defended Shatt al-Arab near Basra, the second headed for Susangerd and the provincial capital of Ahwaz. Supported by heavy artillery barrages, the Iraqis made rapid and significant advances—almost 50 miles in the first few days. The Iraqis made heavy use of artillery and anti-tank guided missiles to break up strongpoints and met with little more than minor resistance from a mix of Revolutionary Guard and gendarmerie infantry forces.

Iraqi units entered Susangerd on September 28; finding it undefended, they pushed on toward Dezful and Ahwaz, crossed the Karun River, and approached the outskirts of Ahwaz and Korramshahr. Iraqi units now threatened all the major cities in southwestern Iran.

Emulating Israeli tactics used in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, Hussein sent formations of MiG-21s in a preemptive strike against Iran’s air bases at Mehrabad, Ahwaz, Dezful, and Abadan, but failed to destroy Iran’s air force on the ground. Iranian jets were housed in hardened shelters and survived intact; Iraqi bombs designed to crater runways could not destroy Iran’s spread-out airfields. Within hours, Iranian F-4 Phantoms took off from the airfields, attacking strategic targets near major Iraqi cities. Although Iran’s 100 sorties were not especially effective, they shot down two aircraft and surprised the Iraqis; the Iranians also used helicopters to fly transport and attack missions. The Iraqi air force, with at least a 3-to-1 numerical advantage, virtually abandoned the skies to preserve its planes.

Iran was in the early stages of transforming its Revolutionary Guard Corps into a serious alternative to the regular army, which meant that much of the initial defense of Iran’s central and southern borders fell to a mix of paramilitary forces, a few scattered regular army brigades, and between 12,000 and 30,000 Revolutionary Guards. The military experience of the Guards consisted largely of training as conscripts in the Shah’s army or low-level fighting against the Kurds or other internal opponents. Meanwhile, the Iranian navy quickly established its mastery of the waters of the Gulf, sinking four enemy vessels and shelling Umm Qasr, the Iraqi oil port on the Faw Peninsula. Within a week, the Shatt waterway was closed for the duration of the war.

Iranian resistance at the outset of the invasion was unexpectedly fierce, if not particularly well organized. Iraqi forces easily advanced in the northern and central sectors and crushed scattered resistance there, but in Khuzestan the attackers encountered unyielding opposition. Iran had rapidly mobilized fiercely loyal Revolutionary Guard units, as well as tens of thousands of untrained and ill-armed popular volunteers called basij. By the end of November, a mixed force of 200,000 troops had been dispatched to the front.

Stalemate

Iraqi armored units paused outside Khorramshahr while artillery attempted to soften up the city’s defenses. When the Iraqis finally pushed into the city of 70,000 people on September 28, they encountered about 2,000 Iranian regulars and a like number of Revolutionary Guards armed with rocket launchers and Molotov cocktails ready to wage a street-by-street fight. While armored units secured the perimeter of the city, Iraqi special forces and Republican Guards, untrained for urban warfare, were committed piecemeal and suffered heavy losses. Iraq finally managed to gain control over most of the city on November 10; the two sides together suffered at least 8,000 troops killed or wounded. After capturing the city, the Iraqis lost their initiative and began digging in along their line of advance; they were now facing a rapidly reinforcing army which had dug in or withdrawn to the foothills of the Zagros Mountains west of Dezful to set up a defensive barrier.

The fighting at Khorramshahr stalled the Iraqi advance on the much larger city of Abadan and the refinery on nearby Abadan Island for two weeks. Although Abadan, separated from Khorramshahr by the Karun River, had been shelled since September 22 from across the Shatt al-Arab, Iraqi troops did not begin surrounding the city until October 10, by which time the Iranians had reinforced it with almost 10,000 regular troops, 5,000 militia, and 50 tanks. An Iraqi mechanized division moved north of Khorramshahr, crossed the Karun River on October 14, and moved to cut off Abadan from Ahwaz. The Iraqis secured the road north to Ahwaz on the 15th, moved south against little resistance, and surrounded most of Abadan Island, but after heavy urban fighting they still could not completely clear the city of its tenacious defenders.

After one month of fighting, the Iraqis had occupied some 7,000 square miles of Iranian territory, but they could not improve on their early gains. The Iraqi thrust virtually ended after the 24-day bloodbath at Khorramshahr. The Iraqi advance stalled, the front stabilized, and the attackers dug in along a 170-mile-wide line on the southern front from Dehloran to Abadan. Heavy rains, which began in December, gave the Iranians five months to build up and reorganize their forces.

The first six months of 1981 were marked by a stalemate on the front and a state of open warfare within Iran as a brutal political power struggle escalated. President Bani-Sadr, in great part responsible for Iran’s initial heroic resistance, came under increasing pressure from clergy members of the Islamic Revolutionary Party. Bani-Sadr, eager to build political support among the armed forces, launched a premature attack by an armored task force that stalled in the mud outside Susangerd and was decimated with heavy losses. When the attack failed, Bani-Sadr was ousted on June 10 and replaced by Khomeini and a three-member Presidential Council. From that point on, the mullahs were in charge of prosecuting the war.

The Iranian Counterattack

Iran achieved its first successful counterattack, in September 1981, when Khomeini persuaded the regular army and militia forces to work together to lift the Iraqi siege of Abadan. A combined force of regular troops and Revolutionary Guards attacked and defeated the well-entrenched Iraqis, capturing 2,000 prisoners and forcing the Iraqis back across the Karun River. Two months later, the Iranians launched a second successful counteroffensive northwest of Ahwaz.

In late March 1982, Iran routed the Iraqi invaders from territory west of Dezful and Shush. The Iranians attacked during a sandstorm and surprised the Iraqi defenders so completely that they collapsed almost immediately. More than 15,000 Iraqi soldiers and 300 armored vehicles were captured, and 1,500 square miles of Iranian territory were retaken.

For the Iraqis, worse was to come in the months ahead. While Hussein redoubled his efforts to marshal international support for a cease-fire, Iran launched another massive offensive in an attempt to retake the captured Iranian port of Khorramshahr. The Iraqis had had 20 months to reinforce the garrison and transform the city’s gutted ruins into a seemingly impregnable fortress. The defenses were surrounded by arcs of huge earthen barriers, barbed wire, and minefields. Iran massed some 150,000 troops outside Khorramshahr and in southern Khuzestan and attacked along three major fronts, again using human-wave assaults and night attacks to surprise the defenders. After weeks of heavy fighting, the Iranians drew closer and closer to the city. The final push came on May 22 when some 70,000 Iranians advanced against 35,000 defenders. Although they suffered horrendous casualties, the Revolutionary Guards and basij finally breached the Iraqi line, and after vicious house-to-house fighting and the loss of 12,000 prisoners, the Iraqis began falling back across the Shatt.

The recapture of Khorramshahr ended the second phase of the war, during which Iran recaptured almost all of its lost territory, at a very high price—over 110,000 casualties, including 60,000 dead. From March 22 to May 24, Iraq relinquished 3,400 square miles of captured territory, at a loss of 40,000 dead, 25,000 captured, 200 tanks, and several hundred artillery pieces. Apart from a few isolated pockets, the Iraqi invasion force had been virtually cleared from Iranian soil. In June, Hussein announced his decision to unilaterally withdraw all Iraqi forces to the international border, but Khomeini quickly made it clear that the war would go on until huge reparation payments were made, Iraq was branded the aggressor, and the Hussein regime was overthrown.

March on Basra

The war’s third phase—from June 1982 to March 1984—began when Iran deployed five full divisions of troops in an attempt to capture the strategic Iraqi city of Basra. Iraq was now defending its own territory and held an advantage in aircraft of 4-to-1 and in operational artillery and armor of 3-to-1. During the previous two years, while the Iraqis occupied large swaths of Iranian territory, their engineers had been hard at work constructing a series of vast and complicated defensive positions along the border and in support lines behind it. Great man-made lakes appeared after Iraqi engineers flooded low-lying areas to form formidable barriers against tanks and advancing troops, a tremendous feat of engineering skill and backbreaking labor. When the Iraqi retreat took place, it was to a line of prepared positions, a series of mutually supporting defensive works as formidable as anything devised since the set-piece battles of World War I.

The Iranians had roughly the same number of troops around Basra as did Iraq, about 80,000. The first Iranian sortie, dubbed “Ramadan al-Mabarah,” began on the night of March 13, 1982. Led by Revolutionary Guard shock troops, four Iranian divisions attacked Iraqi border posts near Salamsheh, with the objective of cutting the main road north from Basra and isolating the city. The Iraqis enjoyed a major edge in firepower, especially artillery, and the attack bogged down after both sides had suffered heavy casualties. The Iranians regrouped and launched another major sortie on July 21, near Zaid, nine miles to the south. At a cost of well over 10,000 men killed, compared to Iraq’s 3,000, the attack wound down after scoring only minimal gains.

The Four Offensives of 1983

Iran launched four offensives in 1983, two of them in Kurdistan, but none achieved any decisive results. The battles brought the total number of casualties to roughly 245,000 men killed in action (65,000 Iraqis and 180,000 Iranians) and at least another 300,000 wounded, and marked the first significant use by the Iraqis of mustard gas on the battlefield.

In early 1984, the Iranians made another push, this time in the southern sector along a broad front covering Dehloran, Mehran, and the Hawizeh Marshes. Two limited attacks were meant as a diversion to draw Iraqi forces away from the main objective, a surprise attack through the Hawizeh Marshes to cut the Basra-Baghdad highway. Iran had deployed a strike force of between 50,000 and 100,000 troops, with another 100,000 in reserve, for the thrust. Three major amphibious attacks, using barges and small craft, targeted Beida, Ghuzail, and the Majnoon Islands. Although the initial attack upon Beida was successful, the Iranians were unable to build up a major bridgehead before the Iraqis rapidly counterattacked with artillery and armor. Iranian reinforcements coming up in small craft were ideal targets for Iraq’s armed helicopters. By February 25, three successive Iraqi counterattacks had overrun the Iranian forces. The fighting degenerated into brutality; Iraqi tanks ran over Iranian infantry and the Iraqis electrocuted others by diverting power lines into the marshes.

At Ghuzail, wave after wave of advancing Iranian militia were slaughtered when they tried to overcome the entrenched Iraqi defenders by sheer force of numbers. During the battle, Iraq used helicopters and artillery to drop mustard gas onto the oncoming Iranian columns, inflicting several thousand casualties. By March 1 the attack was over. The Iranians suffered at least five times as many casualties as they inflicted, losing between 12,000 and 20,000 men.

The “Tanker War”

Iranian troops advancing by boat found the oil-drilling complex in the Majnoon Islands virtually undefended. The “islands,” in reality, were two sand mounds in the marshes to the east of Qurnah. The Iranians were able to dig in unopposed and quickly had 20,000 troops in place. The Iraqis counterattacked on March 6. After more bitter fighting, extensive use of mustard gas, and possibly Iraq’s first experimental use of the nerve gas Tabun, Iraq could fully recover only one of the two islands, giving the Iranians something of a victory. But its losses in the offensive were so severe that Iran was unable to launch major offensive operations for a full year;

In March 1984, the so-called “tanker war” began in earnest when Iraq, using Super Etendard fighters armed with Exocet missiles, began a series of air strikes against shipping and Iranian oil installations in the Gulf, hitting two small Indian and Turkish tankers. After repeated attacks on its main terminal at Kharg Island, Iran felt compelled to respond. Given the absence of Iraqi ships in the Gulf, Iran was forced to use its dwindling air assets to retaliate against the neutral ships of Iraq’s allies, Kuwait in particular. Iran attacked a Kuwaiti tanker near Bahrain on May 13 and a Saudi tanker in Saudi waters on May 16; attacks on ships of noncombatants increased sharply thereafter. Within five weeks, the two sides had combined to hit 11 ships, 10 of them tankers.

158 Sorties Against Iranian Cities

Iran launched nine limited attacks in 1985, keeping considerable pressure on the Basra-Baghdad highway, and Iraq answered with three counterattacks. New battles took place in the Hawizeh Marshes as well, but did not produce the massive numbers of casualties like those of 1984. After a long series of artillery exchanges in February and March that caused 400 civilian deaths, Iran launched a new offensive, Operation Badr, designed to seize Basra or cut it off from the rest of Iraq. The attackers again chose the Hawizeh Marshes as their stepping-off point, believing Iraq would not expect another attack there.

Iran assembled a strike force of 55,000 troops, of which 60 percent consisted of Revolutionary Guards and basij, against an Iraqi force of 10 divisions. On the evening of March 11, the Iranians surged out of the marshes and achieved enough tactical surprise and concentration of force to rapidly break through the first line of Iraqi defenses. As usual, their characteristic human-wave attacks resulted in heavy casualties. The Iranians advanced some 15 miles, and on the night of March 14-15 they laid pontoon bridges across the Tigris River. On the 15th, several militia units actually reached the Baghdad-Basra road, but were unable to sustain or widen their advance.

Iraq felt threatened enough to commit its entire elite Republican Guard division, air force, and massive artillery reinforcements. After flooding large areas in the Iranian rear and deploying armed helicopters, the Iraqis began their counterattack; on March 17, the Iranian lines began to collapse; by the 18th the Iraqis had recaptured all of their lost ground. Iran committed 20,000 troops to another attack against Iraqi positions near Majnoon, but the Iraqis, who had not diverted troops to the fighting farther north, were well prepared. The Iranians attacked on March 19 and 21, but the assault sputtered to an end two days later with the Iranians having achieved nothing except the loss of another 5,000 men, many of them victims of mustard gas attacks.

During March, Iraq launched a series of relatively large-scale air and missile attacks against Iranian cities. In one three-day period some 158 air strikes took place, hitting as deep as Tehran. Iran responded with its first use of Scud-B missiles against Iraqi cities. In mid-August, Iraq began a number of air attacks on Kharg Island, the vital terminal that was responsible for 90 percent of Iran’s wartime exports. French-built Mirage fighters, capable of in-air refueling, gave Iraq the ability to threaten targets anywhere in the Gulf, and it began carrying out long-range raids against new Iranian oil installations in the southern end of the Gulf. By mid-September, Iraq had staged nine major attacks on Kharg Island, cutting Iran’s exports in half.

After making significant improvements in their amphibious assault capabilities, the Iranians now planned to attack in the south, across or around the marshes, to capture the Faw Peninsula and Umm Qasr. By February 1986, with some 200,000 troops massed in the area, Iran was ready for a new series of attacks. On February 9, the first phase of a two-pronged offensive, designed to split Iraq’s defenses, began. Iran’s forces on the northern wing launched three diversionary thrusts—near Qurnah, south of Qurnah, and against parts of the northern Majnoon Island that Iraq had retaken. All three attacks were contained after heavy fighting.

The Capture of the Faw Peninsula

The outcome of the southern attack was different, however, thanks to Iran’s tactic of attacking at night during poor weather. On February11-12, a major amphibious assault was launched on the Faw Peninsula. Although the Shatt was nearly 900 feet wide and crossings were made at night in driving rain, the landings were successful; almost an entire division made it across the water and advanced along the coast of the peninsula. Iraq’s commanders mistakenly believed the main thrust would come to the north and were preoccupied by a massive artillery barrage on Basra. Consequently, they were slow to react when the attack fell on the Faw Peninsula, waiting far too long to commit their reserves.

With heavy rain severely hampering Iraq’s air force during the crucial initial phase of the battle, the outnumbered Iraqi defenders were overwhelmed. At the height of its success, Iran threatened to break out from the peninsula and attack Umm Qasr, which was only 10 miles from Kuwait. This resulted in near-panic in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. An Iraqi counterattack to the south was contained with severe Iraqi casualties—5,000 men killed or wounded in one week.

Continuing bad weather prevented Iraq from making optimal use of its air and artillery superiority, giving Iran 10 nights to reinforce and resupply its troops across the Shatt. Iraq attempted to push Iran off the peninsula through the use of brute force, and both sides threw everything they had into the fighting. The fighting raged for weeks; Iraq pressed home its air attacks at unusually low altitudes to improve their effectiveness and delivered large amounts of mustard and nerve gas. By March 20, both sides were exhausted. Some 20,000 Iranians and more than 30,000 Iraqis were locked into positions just a few hundred feet apart.

Iraq mounted one large counterattack in 1986. Saddam Hussein, feeling the need to secure potential attack routes toward Baghdad, sent a large force to recapture the town of Mehran, defended by 5,000 second-line Iranian troops. A force of 25,000 Iraqis attacked on May 14 and captured Mehran and five neighboring villages. Iran responded by threatening to launch a new “final offensive” while secretly planning to retake Mehran. On June 20, five militia brigades attacked Iraqi positions in the heights above Mehran. The attackers were far superior in mountain warfare, and Iran also made use of poison gas as it rapidly overran Iraqi defenses on July 3. Iraq retaliated by bombing oil shipping facilities inside Iran and stepped up air strikes in the Gulf and against Kharg Island. The Iraqis attacked Sirri Island, a critical new transshipment site in the southern Gulf, for the first time on August 12 and hit three tankers as well.

Iran began massive new mobilization efforts. On August 31, a new offensive began to retake key heights in the Haj Omran area in the north. Iran’s ongoing problems in command and control continued, however, and only limited gains could be accomplished. Iran seized the oil platform at Al Amayah, apparently in an effort to bomb Umm Qasr, but it was quickly retaken by the Iraqis.

On December 23-24, Iran mounted a new offensive, a thrust across the Shatt along a 25-mile front. Once again, repeated massed frontal attacks on well-prepared Iraqi defenses achieved nothing in the way of positive gains—at the cost of horrendous casualties. The Iranians were slaughtered by direct gunfire, artillery, armed helicopters, and air strikes, suffering between 9,000 and 12,000 casualties.

The Fight For Basra

By early 1987, Iran and Iraq both had about 200,000 troops deployed along the southern front near Basra, Iraq’s second largest city. Again, Iran launched a massive attack. The first wave of 60,000 troops moved rapidly into positions near Salamcheh, a border crossing point 12 miles from Basra. The attackers faced severe difficulties from the outset—the land and water barriers around Basra had been vastly improved. The Iraqis had created a huge man-made lake across the Shatt from Basra called Fish Lake, which was filled with sensors, underwater obstacles, and barbed wire entanglements. Basra itself was a virtual fortress with six separate defensive rings, and Iraq maintained strong forces in the area—four army divisions and five Republican Guard brigades.

The Iranians were able to achieve some degree of tactical surprise and managed some significant early successes. On January 9, they struck in a line toward Khusk at two points northeast of Fish Lake and at another point to the southeast in the direction of Salamcheh. Iran committed some 50,000 troops to the initial assault, including several waves of basij, many of them 14- or 15-year-old volunteers with little or no military training. On the first day, a breakthrough was made at the city of Duayji, and although Iraq used massive firepower, air strikes, and poison gas in an attempt to seal the breach, the Iranian forces surged forward, capturing other positions near the border.

Iran captured Salamcheh, 19 miles south of Basra, and penetrated the first two defensive lines near Khusk, 40 miles to the north. This gave the attackers a secure bridgehead across the border, and fresh Iranian forces began advancing in strength up the eastern side of the Shatt, arriving at a point about 12 miles south of the outskirts of Basra. On January 10, an Iraqi counterattack failed; some of Iran’s initial assault forces penetrated the first two defensive rings around Basra. Fighting intensified.

As the Iranians moved forward onto dry land and attacked Basra’s main defenses, they increasingly suffered from a relative lack of firepower, mobility, and ability to move supplies and ammunition. Iraq committed its entire air force, flying some 500 missions on January 14-15 alone. Iran responded by sending in 50,000 reinforcements and launching a minor naval assault on several islands near the Shatt’s eastern shore. The main Iranian battle forces were unable to link up as planned, and in spite of the reinforcements it had brought up, Iran began taking so many additional casualties that the attack finally lost momentum. By January 16, the fighting had cost Iran an additional 40,000 casualties.

By early February, Iran had suffered at least 17,000 killed and roughly 40,000 wounded, and possibly more; Iraq had lost 6,000 dead and roughly 14,000 wounded. On February 12, Ayatollah Khomeini declared that the war was a “holy crusade” and vowed that the Iranians would fight until victory was achieved. At least 30,000 Iranian troops still held positions near Fish Lake, and more volunteers were sent to the front. Heavy fighting continued until mid-February with little change in the tactical situation. Iran had secured positions as close as six miles from Basra but could go no farther.

The War’s Increasing Toll on Civilians

The carnage at Basra led Iraq to intensify the war on Iranian cities. In January 1987 alone, the Iraqis conducted over 200 long-range air and missile strikes. When the month ended, the Iranians claimed that 1,800 of their citizens had been killed and 6,200 wounded. Iran could not retaliate in the air, but it did launch Scud missile attacks on Baghdad and Basra.

On April 6, Iran launched yet another costly series of human wave attacks against the Iraqi defenses around Basra; 35,000 Revolutionary Guards attacked from positions Iran had won in the earlier fighting. This time, however, the Iraqis were not surprised. For three days the Iranians sent repeated waves of troops against well-prepared defenses—the result was a bloodbath. Iran had another 9,000 casualties, with a high proportion of killed to wounded, while Iraq suffered losses of just 2,000.

The ground fighting in 1987 seemed to indicate that Iran could win limited tactical victories but lacked the capability to make a major strategic breakthrough. Both sides had taken heavy losses, with Iran suffering three to six times as many casualties as Iraq. Iran’s total casualties for the war had already surpassed 1 million men killed and wounded; over 2 million Iranian civilians were homeless. On the Iraqi side, the once vibrant city of Basra was virtually deserted, and Iraq had a large refugee population as well.

War’s End

The course of the war changed radically in the spring of 1988, when Iraq switched from static defense to massive counteroffensives. In early 1988, Iran had decided to switch its emphasis to campaigns in the north, leaving the southern sector undermanned and vulnerable. Iraq had 900,000 troops arrayed along the front compared to 600,000 for the Iranians. Iraq chose April 1, the first day of the Ramadan holiday, to mount one of its largest offensives of the war. Iran was rotating its troops and had left Faw gravely undermanned. The Iraqi assault, during which they enjoyed a 6-to-1 advantage in manpower, achieved almost total tactical surprise, and the defenders never recovered from the initial attack. Just 36 hours after the massive attack began, the Iranians were streaming back across the Shatt in disarray, abandoning their equipment.

On May 25, Iraq launched its second sortie along a 15-mile corridor to the east and southeast of Basra after one of the heaviest artillery bombardments in history. Iraq enjoyed a huge advantage in armor, outnumbered the defenders by at least 3-to-1, and also employed chemical weapons during the initial phase of the attack, which struck the Iranians near the southern edge of Fish Lake, six miles south of Basra. Although the Iranians resisted fiercely and mounted a major counterattack, the combination of Iraq’s mass and chemical weapons broke the Iranian resistance. Five demoralized Iranian divisions began to retreat. Many units abandoned their equipment, and Iraq captured 90 tanks. After 10 hours of combat, the Iraqi flag once again flew over the desert border town of Salamcheh. All the hard-won gains that Iran had achieved in 1987 at a cost of 50,000 dead were lost in a single day.

Iraq’s next objective was the city of Mehran. On June 18, a massive new offensive, backed by 530 sorties flown by Iraqi jets and helicopters again employing chemical weapons, was launched. Iraqi troops, backed by anti-Khomeini Iranian mujahedin, captured the city of Mehran and several of the surrounding heights. Iraq launched another major offensive one week later against the last remaining Iranian positions in Majnoon and the Hawizeh Marshes. Once again, the attackers enjoyed massive advantages in manpower, artillery, and armor. The Iraqi force, which included regular army units, militia, a paratrooper brigade, and a chemical corps, rapidly enveloped the enemy positions in both Majnoon and the marshes. After just eight hours, the Iranians collapsed and began withdrawing. Four devastating defeats had driven them back across the border, and the Iranian forces no longer had the will to resist the resurgent Iraqis.

An Iranian ground offensive to retake Salamcheh failed, and on July 3 another disaster struck Iran. The United States Navy cruiser Vincennes, battling Iranian gunboats in the Strait of Hormuz, mistook an Iranian civilian airliner for an F-14 jet and launched two guided missiles, downing the airliner and killing all 290 passengers and crew. The catastrophe had a profound effect on Iran’s leaders, some of whom believed the airliner had been shot down deliberately. Khomeini, his armies defeated, his country bankrupt, and his industries near collapse, agreed to begin cease-fire negotiations. On July 18, Iran notified the United Nations that it would accept Resolution 598; although sporadic fighting continued for a month, the war was effectively over. On August 8, 1988, the agony finally came to an end.

Saddam Hussein’s Post-War Atrocities

Once the fighting stopped, Saddam Hussein committed one of the greatest atrocities of the 20th century by a government against its own people. The day after the cease-fire went into effect, Iraqi warplanes began strafing Kurdish villages in the north, dropping poison gas and rocketing fleeing citizens. Some 5,000 inhabitants perished and another 100,000 refugees headed for the borders of Iran and Turkey. The end of the war for Iraqi citizens meant that they would continue to be strictly monitored, arrested, tortured, imprisoned, or killed by Hussein’s brutal regime.

$350 Billion on a Senseless War

The war had ended, but the rebuilding had yet to begin. Along the Iran-Iraq border, whole villages had disappeared, destroyed either by invading Iraqi troops or by Iranian troops pounding them to rubble in an attempt to liberate them. The true human and economic cost of eight years of unrestrained brutality is impossible to measure. The numbers of people, civilian and military, who were killed, maimed, or sickened by chemical agents can only be estimated. Possibly as many as 1 million people were slain and 1.5 million wounded; another 2 million became refugees.

Neither country came anywhere near achieving even the most modest of its war aims. The borders were unchanged; both armies ended the war in essentially the same position they were in at the outbreak of hostilities. Together, the opponents had squandered some $350 billion on a senseless war of attrition engineered by two venal and intransigent autocrats. A generation of long-suffering Iranians and Iraqis deserved far better.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments