By Nicholas Varangis

“One of the greatest heroes in American history never fired a bullet.” That is the tagline of Director Mel Gibson’s 2016 film, Hacksaw Ridge. The film, which was met critical acclaim, tells the incredible true story of Desmond Doss, the first conscientious objector to receive the Medal of Honor. But who is Desmond Doss? And what makes his story so unique?

Before Hacksaw Ridge: A Seventh-Day Adventist Enlists

Desmond Thomas Doss was born on February 7, 1919 in Lynchburg, Virginia to Thomas and Bertha E. Doss. Doss’ family was deeply spiritually divided.

His father, left devastated by the Great Depression, was not a deeply religious man and drank heavily. His mother meanwhile devoutly followed the Seventh Day Adventist faith and had Doss and his two siblings attend church regularly. Component in the beliefs of Seventh Day Adventists is the strict adherence to the Ten Commandments.

The Sixth Commandment, ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill’ would especially resonate with young Desmond Doss. An argument between Thomas Doss and his brother-in-law escalated when Thomas drew a firearm. Bertha Doss stepped in between them and talked Desmond’s father into giving over his gun and surrendering to the police. To Desmond, the encounter was all too reminiscent of Cain and Abel, the biblical story of fratricide.

From that point onward Desmond Doss grew up to personally object to violence and murder of all kind, to include instances of self-defense, and swore to never hold a weapon again.

However, when the United States was thrown into the wars in Europe and the Pacific, Doss’ religious and moral convictions would be put to the test.

Why Desmond Doss Was a Conscientious Objector in World War II

As America watched the opening stages of the Second World War unfold, the U.S. government was preparing to enter into a total war of unprecedented scale. Recognizing the importance of increasing the manpower of the U.S. Military, Congress passed the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. The law, which became effective in September 16, 1940, instituted a peacetime draft for the first time in U.S. history.

Selective Service included dozens of classifications, which covered exemptions and alternatives to classification ‘I-A’: “Available for unrestricted military service”. For conscientious objectors, two main categories could be chosen: I-A-O, available for noncombatant military service, and IV-E, available for assignment to limited “work of national importance”. It was the first time provisions were made for conscientious objectors in an American war.

When Doss was called up for the draft in 1942, he made his objection to killing known. However he made an important distinction between his personal objection and his support for the war effort, preferring the term “Conscientious Cooperator” for himself. As such, Doss rejected the alternative service option offered to him and enthusiastically enlisted in the U.S. Army. For the purposes of the draft, he would begrudgingly accept the title of conscientious objector.

In the Army, Doss would quickly adapt and excel in his role as a combat medic.

The Medic’s War

In keeping with his beliefs, Doss refused to carry a weapon. His position on violence unsurprisingly did not make him popular within the Army. Doss would face harassment and persecution for his deeply held religious conviction against violence throughout his training.

The position Doss held may have been noncombatant in name and theory. However Doss would soon discover that his principles would be challenged not only by his fellow soldiers, but also by the brutality of the Pacific Theater, where war had no rules.

The modern combat medic has been considered to have a privileged role on the battlefield. In the Civil War, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson set a trend by ordering that all Union medical officers held under his commend be considered noncombatants. The First Geneva Convention a few years later would codify similar policies regarding medical personnel. Chapter VI, Article 25 of the Geneva Convention states:

“Members of the armed forces specially trained for employment, should the need arise, as hospital orderlies, nurses or auxiliary stretcher-bearers, in the search for or the collection, transport or treatment of the wounded and sick shall likewise be respected and protected if they are carrying out these duties at the time when they come into contact with the enemy or fall into his hands.”

Likewise, it was, and still is, considered a war crime to knowingly fire on medical personnel.

Although unarmed and protected by the conventions of war, Doss faced just as much danger as any combat infantryman, in fact perhaps even more. Not only were Army medics required to brave the same conditions as the average infantryman, but they were also targets for Japanese soldiers and snipers. Japan was not a signatory of the Geneva Convention, and Japanese commanders encouraged the targeting of medical staff for tactical effect on the battlefield. Doss himself described this:

“The Japanese were out to get the medics. To them, the most hated men in our army were the medics and the BAR men… they would let anybody get by just to pick us off. They were taught to kill the medics for the reason it broke down the morale of the men, because if the medic was gone they had no one to take care of them. All the medics were armed, except me.”

How He Became a Medal of Honor Recipient

Doss joined the U.S. island-hopping campaign at the Battle of Guam, and would continue it to Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. By the time he reached Okinawa, in April 1945, Doss had already earned a Bronze Star for saving the lives of the men in his company.

In the Battle of Okinawa Private First Class Desmond Doss’ valor and heroism would save dozens more lives, earning him the Medal of Honor.

Desmond Doss’ Medal of Honor citation speaks for itself:

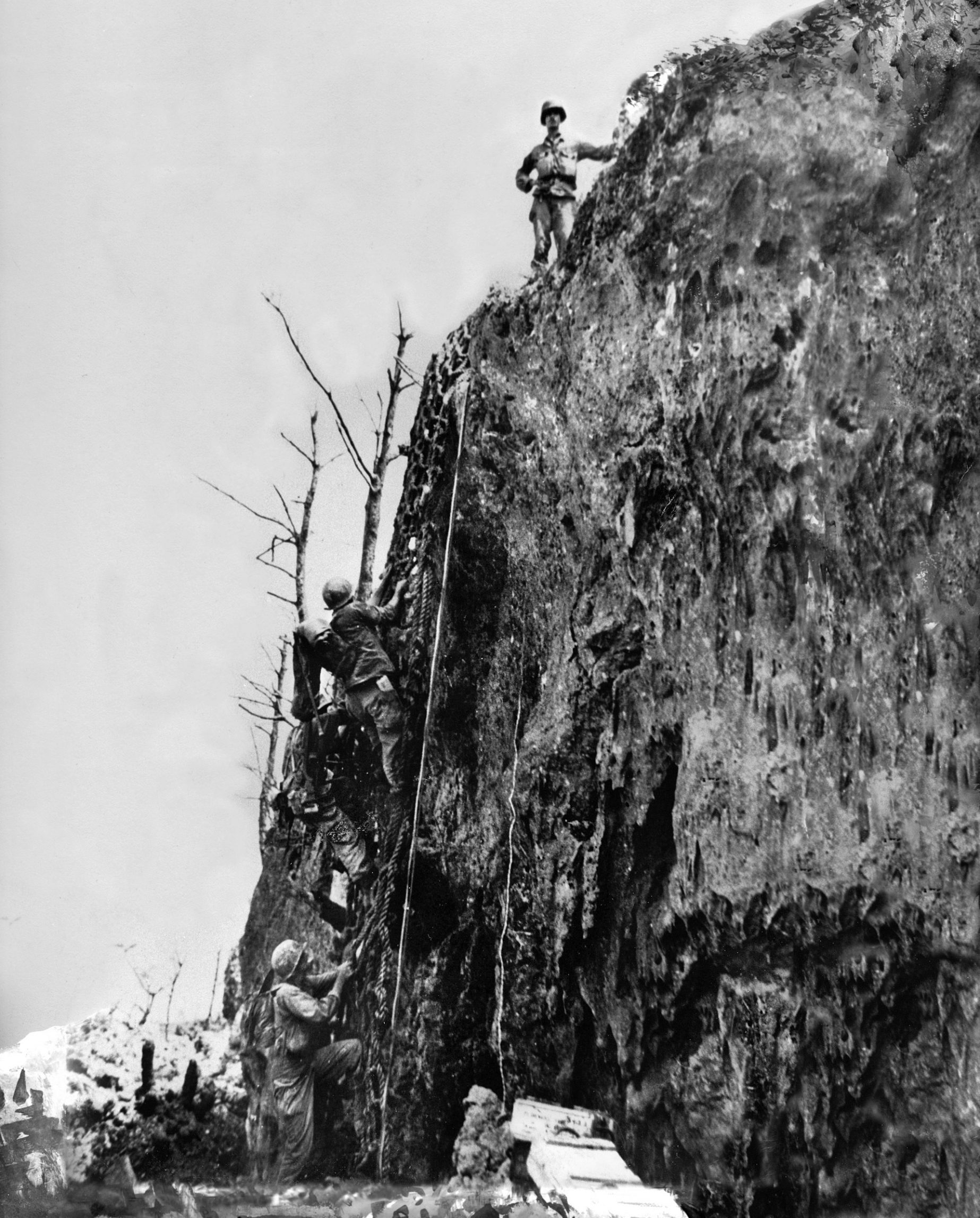

“He was a company aid man when the 1st Battalion assaulted a jagged escarpment 400 feet high As our troops gained the summit, a heavy concentration of artillery, mortar and machinegun fire crashed into them, inflicting approximately 75 casualties and driving the others back. Pfc. Doss refused to seek cover and remained in the fire-swept area with the many stricken, carrying them 1 by 1 to the edge of the escarpment and there lowering them on a rope-supported litter down the face of a cliff to friendly hands.

On 2 May, he exposed himself to heavy rifle and mortar fire in rescuing a wounded man 200 yards forward of the lines on the same escarpment; and 2 days later he treated 4 men who had been cut down while assaulting a strongly defended cave, advancing through a shower of grenades to within 8 yards of enemy forces in a cave’s mouth, where he dressed his comrades’ wounds before making 4 separate trips under fire to evacuate them to safety.

On 5 May, he unhesitatingly braved enemy shelling and small arms fire to assist an artillery officer. He applied bandages, moved his patient to a spot that offered protection from small arms fire and, while artillery and mortar shells fell close by, painstakingly administered plasma. Later that day, when an American was severely wounded by fire from a cave, Pfc. Doss crawled to him where he had fallen 25 feet from the enemy position, rendered aid, and carried him 100 yards to safety while continually exposed to enemy fire.

On 21 May, in a night attack on high ground near Shuri, he remained in exposed territory while the rest of his company took cover, fearlessly risking the chance that he would be mistaken for an infiltrating Japanese and giving aid to the injured until he was himself seriously wounded in the legs by the explosion of a grenade. Rather than call another aid man from cover, he cared for his own injuries and waited 5 hours before litter bearers reached him and started carrying him to cover. The trio was caught in an enemy tank attack and Pfc. Doss, seeing a more critically wounded man nearby, crawled off the litter; and directed the bearers to give their first attention to the other man. Awaiting the litter bearers’ return, he was again struck, this time suffering a compound fracture of 1 arm.

With magnificent fortitude he bound a rifle stock to his shattered arm as a splint and then crawled 300 yards over rough terrain to the aid station. Through his outstanding bravery and unflinching determination in the face of desperately dangerous conditions Pfc. Doss saved the lives of many soldiers. His name became a symbol throughout the 77th Infantry Division for outstanding gallantry far above and beyond the call of duty.”

The Legacy of Desmond Doss

Pfc. Desmond Doss was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Harry S. Truman 71 years ago, on October 12, 1945.

After the war, Doss spent five years recovering from the injuries he sustained during the war. During his recovery, he would also lose a lung to tuberculosis. In the 1950s Doss moved with his wife, Dorothy Pauline Doss, to Rising Fawn Georgia. From 1946 to present, Doss’ story has been depicted in numerous media, including the April 1946 edition of True Comics, his biography The Unlikeliest Hero (1967), the documentary film Conscientious Objector (2004), and others.

Desmond Doss passed away at the age of 87 in 2006. You can read more about he Battle of Hacksaw Ridge in our August 2021 issue of WWII History magazine.

Audie Murphy and film producer Hal B. Wallis tried unsuccessfully to persuade Desmond T. Doss to sell them the rights to his life story. Doss refused all offers to turn his story into a film.

I continue to be fascinated by Desmond Doss amazing story which I reread at every opportunity. Every time I do I make calculations about what he did. the number of times he came close to death, the cumulative hours and minutes that he was under direct fire, the number of executive decisions he made, the way he managed himself in prolonged dire circumstances. The sheer amount of intellect, and brainpower he generated, used and consumed. That in addition to his strong faith in god and himself, it’s mind blowing to me. He seems super-human. I would like to have known him.

Brave man motivated by the courage of his convictions.