by Eric Niderost

The Qing originally sprang from the Juchen peoples, hard-riding tribesmen who occupied the territory north of Korea. In the 17th century Nurhachi of the Ansin Gioro clan united the Juchen tribes under his leadership. He created military units called “Banners,” each distinguished by a colored flag.

Eventually there were eight banners; the list including bordered yellow, plain yellow, plain white, bordered white, plain red, bordered red, bordered blue, and plain blue. Eventually the Jurchen tribes became known as the “Manchu,” and their territory “Manchuria.” Nurhachi laid the foundation of Manchu greatness, but it was his sons Abahai and Dorzon who really created the Qing dynasty. The Manchu army became multiethnic, welcoming Mongols and Chinese into its ranks. In time, eight banners of Chinese and eight banners of Mongols were formed, joining the original Manchu formations for a total of 24 banners.

Banner Units: Military and Civic Functions

Eventually, these bannermen had both military and civic functions. Although there were 24 banner units, in fact, officially they were always just the “Eight Banners.” After the Manchus took over China in 1644 and placed their Qing dynasty on the Dragon Throne, the pre-existing Chinese Army was reorganized with the title “the Green Banner.” The green banner became a kind of national police force.

One estimate places the 19th-century strength of the bannermen at 200,000, the green banner at 500,000. These figures are inflated, because corrupt officials created fictional troops to pocket army funds. China had once led the world in military technology, inventing gunpowder and the crossbow in the Middle Ages. But although the Chinese Army may have had 800,000 men, sheer numbers alone could not disguise the internal rot, a deep malaise caused by the chronic failure to modernize.

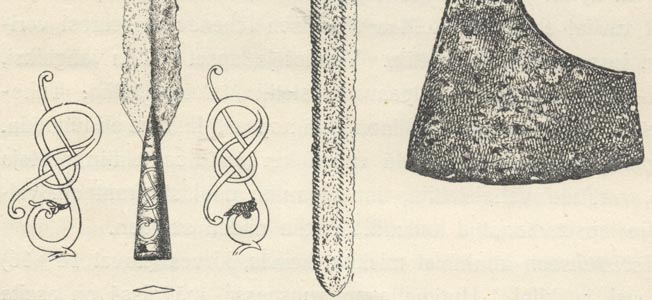

The Qing emperors, like Chinese society at large, had become intensely sinocentric, so focused on the greatness of China they failed to recognize the technological developments in Europe and America. By 1860 the army was hopelessly out of date, its men armed with 17th-century or even medieval weapons. Some Chinese soldiers carried matchlocks or jingals, the latter a curious weapon that seemed half musket, half hand-held artillery.

[text_ad]

Fighting the British for the Third Time

The jingal had a 1.5-inch caliber and fired balls from four ounces to a pound. They were so cumbersome that to be fired they had to be propped on a wall, or even another man’s shoulder. Other Chinese troops were equipped with swords, crossbows, bows and arrows, spears, and a curious kind of polearm that looked like a trident. By contrast, the red-coated British infantryman had as his standard weapon the 1853 percussion Enfield Rifled Musket, sighted to 1,200 yards.

The 1860 conflict was the third time the Chinese had fought the British. The first China war, also called the “Opium War,” took place from 1839 to 1842. The Second China War was fought largely from 1857 to 1858. By 1860 the Qing had had 20 years to see the handwriting on the wall, yet they failed to act.

In 1860 bannermen were a magnificent anachronism, their dress and weaponry scarcely changed for over two hundred years. A British eyewitness recalled, “The Tartars [probably bannermen] were dressed in the ordinary Chinese black hat of silk … and had two squirrels’ tails projecting from the hat behind. They had on light colored jackets over a long under-garment of darker material, and blue trousers tucked into long tartar boots. They rode in short stirrups, and were mounted on stout hardy working ponies.”

The bannermen were superb horsemen, performing dazzling feats of equestrianship with grace and ease. Matchlock-wielding horsemen could fire and reload their pieces, and bowmen discharge a hail of arrows, all while riding at full gallop.

The typical Chinese foot soldier wore a sleeveless surcoat over a loose smock. The surcoat had a circle on the front and back that gave his unit and a character that meant “courage” or “bravery.” In this period Chinese men adopted the Manchu custom of shaving the forehead but having a long braided queue or pigtail behind. Chinese or Manchu officers were distinguished by bamboo hats topped by a decorative fringe of red hair on top.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments