By James M. Powles

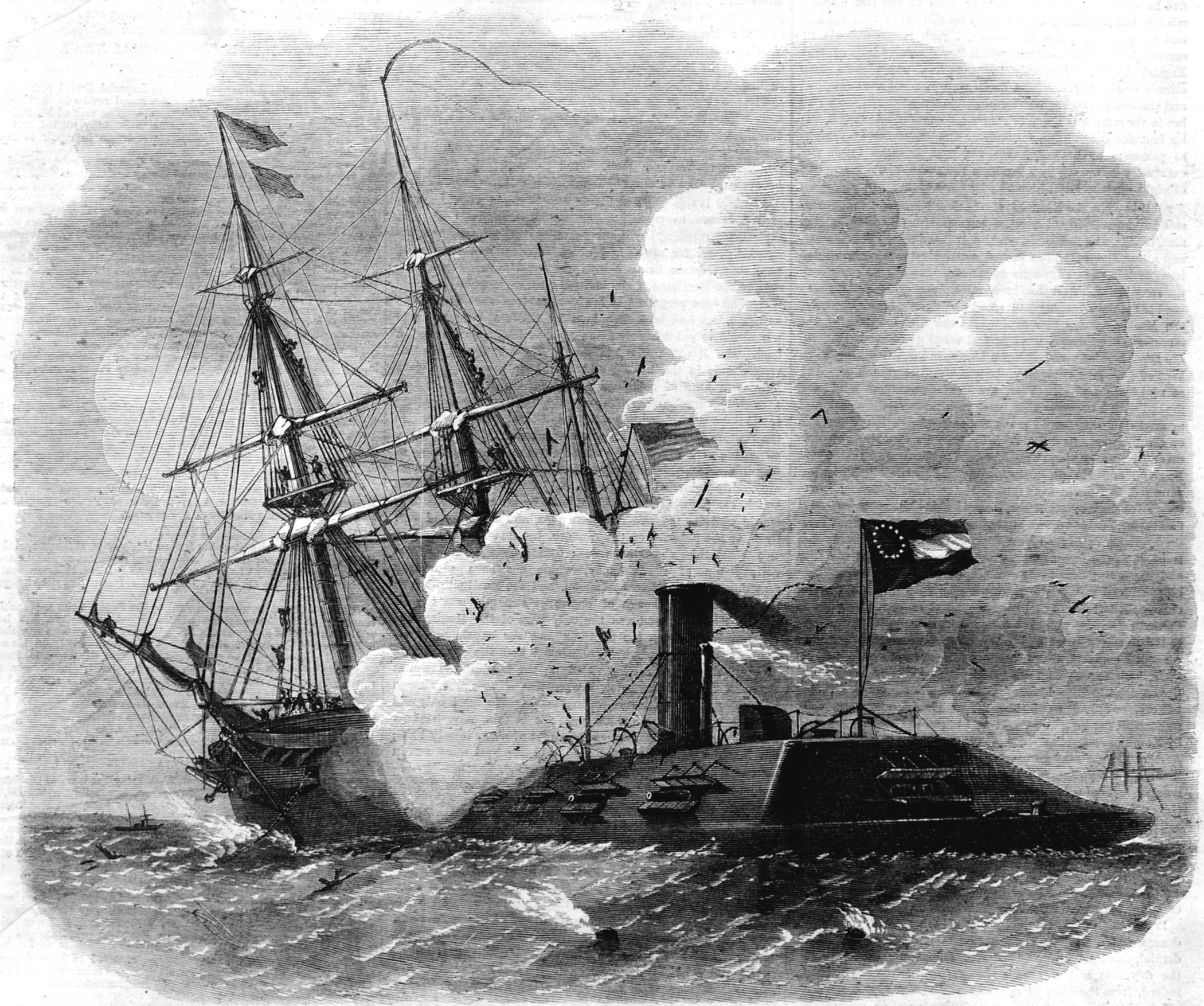

March 8, 1862, dawned sunny and mild at Hampton Roads, Virginia. To the men of the Union blockading squadron, the day seemed like any other. At Gosport Navy Yard, near Norfolk, the Confederates had constructed an ironclad vessel on the hull of the partially destroyed USS Merrimack. Renamed CSS Virginia, the ironclad was reportedly ready to challenge the Union blockaders. Standing watch off Newport News for this supposedly indestructible ironclad were the 24-gun sloop of war Cumberland and the 50-gun frigate Congress. At 12:45 pm, lookouts sighted Virginia, accompanied by two smaller Confederate vessels, heading into Hampton Roads from the Elizabeth River. Both Union warships immediately cleared for action.

“The Carnage was Frightful”

On board Cumberland was Lieutenant Thomas O. Selfridge, an aggressive and fearless 26-year-old United States Naval Academy graduate. In charge of the forward battery of six guns, he would soon face the brunt of Virginia’s raking fire. Around 2:30 pm, Virginia bypassed Congress and headed straight toward Cumberland, her captain having decided to ram the more heavily armed sloop of war. Cumberland opened fire as soon as her guns could be brought to bear, but she took a terrible pounding as Virginia moved across the warship’s bow to get into position to ram.

Selfridge ran from gun to gun, firing as fast as he could, but to no avail. Cumberland’s shells bounced harmlessly off the ironclad’s sloping sides. Meanwhile, Virginia’s deadly fire tore through the Union vessel’s wooden hull, sending lethal pieces of wood whizzing about and decimating the warship’s crew. Selfridge later recalled: “The dead were thrown to the disengaged side of the deck; the wounded carried below. The carnage was frightful.”

After crossing Cumberland’s bow, Virginia turned and struck Cumberland on the starboard bow, penetrating the side under the berth deck. For a few minutes the two vessels were locked together, with the now-sinking Cumberland pulling the ironclad down with her. Virginia was saved when her ram broke away, allowing her to slowly pull away. Cumberland’s crew continued to fire for half an hour, until ordered to abandon ship.

Selfridge, one of the last to leave, later recalled his narrow escape. “Throwing off coat and sword, I squeezed through gun port,” he wrote. “In doing so, however, the heel of my boot became jammed against the port sill by the gun. I finally succeeded in wrenching off the boot-heel and thus freeing myself. Then jumping into the icy water, encumbered by boots and clothing, I swam to the launch astern and was picked up exhausted.” Looking back, Selfridge saw his proud ship go under “bow first and her stern high in the air.” It was the first of several close calls he would have during the war.

Thomas Selfridge: A By-the-Book Officer

Selfridge was born on February 6, 1836, to Navy Captain Thomas Oliver Selfridge and Louisa Cary Soley in Charlestown, Massachusetts. In 1851 he was appointed to the United States Naval Academy, where he graduated in 1854 at the head of his class. His first assignment was on USS Independence, the flagship of the Pacific Squadron. Sailing from New York on a two-year cruise, Independence traveled to California, Hawaii, Samoa, Chile, and Panama. Upon his return, Selfridge was promoted to midshipman and served as acting master aboard the Coast Survey schooner Nautilus. At the outbreak of the war, he joined Cumberland at Gosport Navy Yard for blockade duty on the James River.

Selfridge was a dedicated, intelligent, and gifted officer who excelled in seamanship and gunnery. He was also a demanding, “by the book” officer, which did not endear him to his subordinates. Personally brave, he sometimes let his courage overcome his better judgment. After Cumberland’s sinking, he was ordered to take temporary command of the ironclad Monitor. A few days later, he was replaced as captain by Lieutenant William Jeffers. After a month’s leave in Boston, Selfridge was recalled to Hampton Roads and given command of Illinois, a large coastal steamer chartered by the government. When the charter was revoked a few days later, he became flag lieutenant on the staff of Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough, commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron.

An Early Submariner

When Goldsborough resigned in July, Selfridge went to Washington to seek a new ship. He was offered command of the experimental submarine USS Alligator. At first, he turned it down, believing the submarine could not be successfully developed for practicable use, but he soon reversed his decision. Alligator was a 47-foot-long submersible designed by French engineer Brutus De Villeroi to counter the Confederate ironclad Virginia. Seeing his new command for the first time at the Washington Navy Yard, a less-than-elated Selfridge described her as being “little more than a cigar-shaped hull with crude man-power propulsion machinery inside.”

On August 4, Selfridge decided to take the submarine on a short cruise down the river. Alligator had not gone far when her bow suddenly began to sink. Selfridge, standing on deck, looked into the conning tower hatch and discovered “a rush being made by the men to get out.” The sub’s air purification system had failed. The men made it safely to the deck, and the helpless submarine drifted downriver until Selfridge managed to hail a nearby schooner and have the submarine towed back to the Navy Yard.

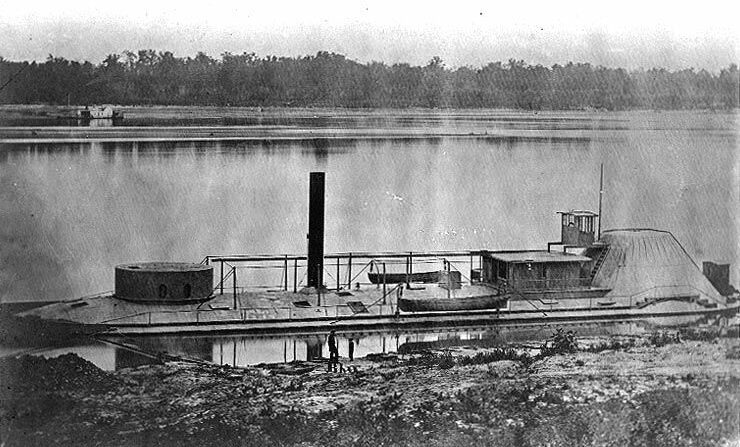

Mississipi Squadron: In Command of the Ironclad USS Cairo

Disgusted by the sub’s performance, Selfridge immediately requested a transfer to the Mississippi Squadron. Upon reaching Cairo, Illinois, he found that he had been promoted to lieutenant commander and given command of USS Cairo, one of the city-class river ironclads built by James Eads. Selfridge took over at Helena, Arkansas, on September 12. Cairo patrolled the river above Memphis for several weeks until Acting Rear Admiral David D. Porter ordered Selfridge to bring his vessel back to Helena. Porter was preparing to assist the Army in a new campaign against Vicksburg, Mississippi. On December 8, Selfridge joined the Union flotilla anchored off the mouth of the Yazoo River.

On the morning of the 11th, the tinclads Marmora and Signal ventured up the Yazoo on a reconnaissance. As they neared the Confederate earthworks at Drumgould’s Bluff, lookouts sighted torpedoes in the water. Upon returning, the captains of the tinclads said they could remove the torpedoes if given protection by one or two gunboats. Selfridge, always willing to go in harm’s way, requested permission to lead the mission to clear the torpedoes. The next morning, the two tinclads, escorted by Cairo and Pittsburg, along with the ram Queen of the West, entered the Yazoo. Later that morning, disaster struck. Marmora was 100 yards ahead and hidden from Cairo’s sight by a bend in the river when her crew opened fire with muskets on a suspected torpedo. Fearing that the tinclad was being fired on from shore, Selfridge moved to support her. As he neared Marmora, Selfridge ordered the firing stopped. He had a boat lowered from each vessel to determine what the tinclad had been shooting at.

Selfridge described what happened next. “The head of the Cairo having got in toward shore, I backed out to straighten upstream, and ordered the Marmora to go ahead slow,” he wrote. “I had made but a half a dozen revolutions of the [paddle] wheel and gone ahead perhaps half a length, the Marmora a little ahead, leading, when two sudden explosions in quick succession occurred, one close to my port quarter, the other apparently under my port bow—the latter so severe as to rise the guns under it some distance from the deck. The Cairo sunk in about twelve minutes after the explosion.”

The Red River Expedition

After losing Cairo, Selfridge was given command of Conestoga, a river steamer that had been converted into a gunboat, and assigned to patrol the Mississippi between the White and Arkansas rivers. For the next several months, he protected Army supply steamers and military transports and fought frequent skirmishes with Confederate guerrillas and hidden shore batteries.

In May, Selfridge and his crew were transferred to the gunboat Manitou while Conestoga was undergoing repairs. Early the next month, he was sent with two 8-inch guns from Manitou to assist in the siege of Vicksburg. He was relieved of this duty a few days before Vicksburg surrendered and returned to Conestoga. Shortly after resuming command of the gunboat, Selfridge led an expedition up the Red River to capture cotton and disperse Confederate forces along the river.

After that expedition, he assumed command of the naval station at Vicksburg and continued patrolling the Mississippi. In March 1864, Conestoga was carrying a cargo of ammunition down river from Vicksburg to Porter’s fleet, when it was accidentally sunk by the USS General Price 10 miles below Grand Gulf on March 8. General Price was found at fault for the accident. When Selfridge returned to the fleet and reported the loss, Porter remarked, “Well, Selfridge, you do not seem to have much luck with the top of the alphabet, I think that for your next ship I will try the bottom.” Porter gave him the command of the ironclad river monitor USS Osage, mounting two 11-inch guns in a single turret, just in time to take part in the Red River expedition.

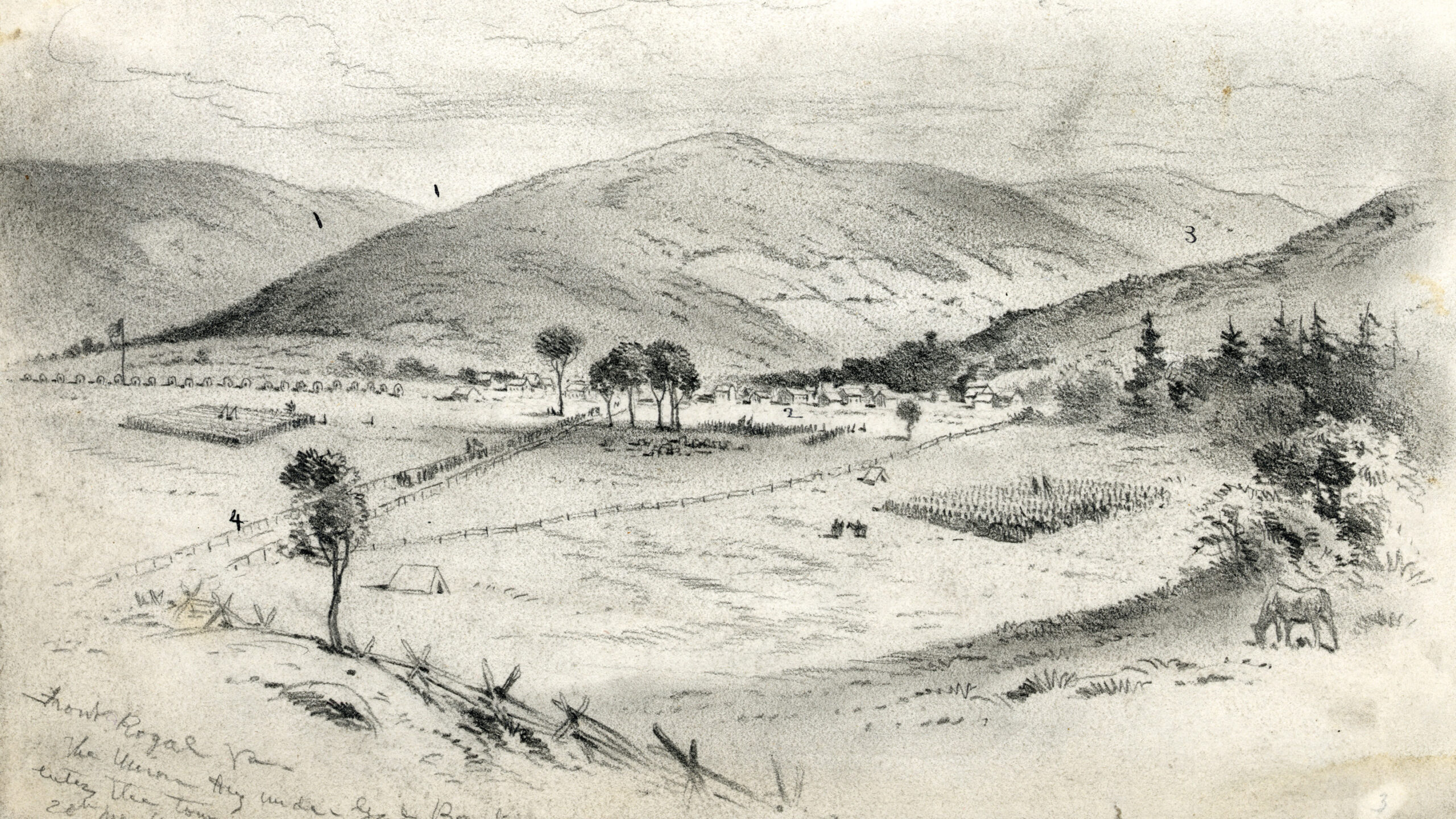

The expedition was a joint Army-Navy venture consisting of a land force commanded by Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks and a squadron of ironclads and gunboats under Porter escorting the troops of Brig. Gen. A.J. Smith. Early on March 12, the gunboats and transports started upriver. The water in the river was exceptionally low for that time of the year.

The first obstacle Porter encountered after entering the river was Fort DeRussy, a Confederate earthen fortification build to protect the river against Union incursions. While several of Porter’s vessels were clearing the obstructions planted below the fort, Smith disembarked his men and captured the fort on the evening of March 14. The next day Porter and Smith reached Alexandria, where they waited for Banks. In the meantime, Selfridge was directed to pick up some cotton. Selfridge took command of one of the smaller gunboats and an empty transport and went downriver in search of cotton. Several days later he returned to Alexandria with some 800 bales.

While he was gone, the river had risen high enough for the gunboats and transports to pass over the falls. By March 25, Banks and his army had joined Porter at Alexandria. Within a few days, Banks began moving his army out of Alexandria toward Shreveport, which he intended to capture. Banks requested naval assistance, and despite the low water, Porter agreed. On March 31, the advance guard of the fleet, comprising eight gunboats, including Osage, proceeded upriver to Grand Ecore to cover the Army when it reached that point after a march overland.

A Fighting Retreat

On April 3, Banks and Porter met up at Grand Ecore, where most of Smith’s troops disembarked from the transports to reinforce Banks. Three days later, Banks continued his journey to Shreveport. The next day, Porter transported Kilby Smith’s 1,700-man division to Loggy Bayou. Porter arrived at Loggy Bayou in the afternoon of the 10th, only to find that Banks had been defeated by the Confederates at Sabine Crossroads and was retreating. Porter had no alternative but to head back downriver. Selfridge brought up the rear.

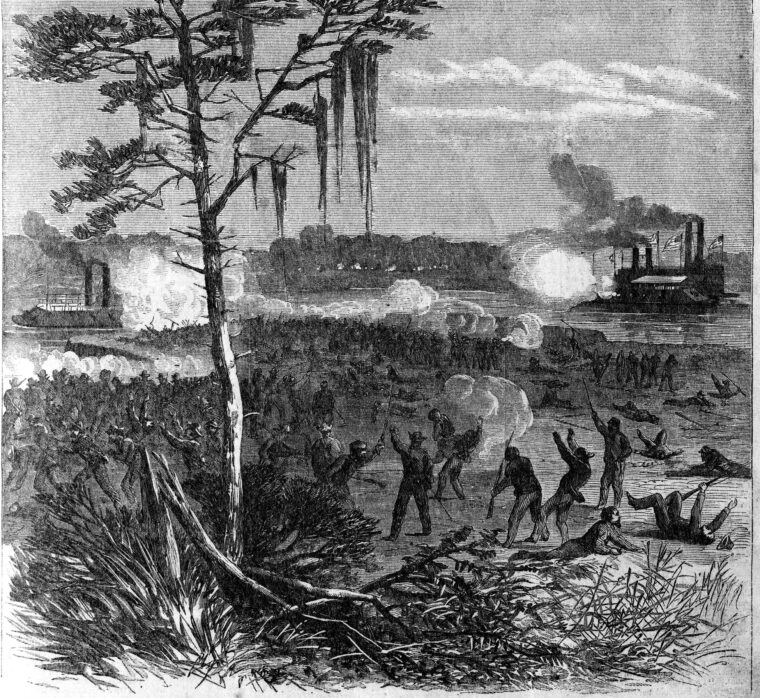

Because the river was low and the current swift in the bends, Selfridge found Osage almost unmanageable while descending. On the morning of the 12th, he lashed the transport Blackhawk to Osage to assist the lumbering ironclad. The descent went well until late afternoon, when Osage went aground opposite Blair’s Landing. Close by were two other transports and the gunboat Lexington. As Selfridge was trying to free Osage, Blackhawk spotted a large of body of Confederates closing in on the stalled vessels. The force, under Brig. Gen. Thomas Green, consisted of a large number of dismounted cavalrymen and several pieces of artillery. The Confederates opened a murderous fire of muskets and artillery on the Union vessels. The two gunboats replied in kind.

Selfridge reported to Porter: “I waited till they got into shelling range, and opened upon them a heavy fire of shrapnel and canister. The rebels fought with unusual pertinacity for over an hour, delivering the heaviest and most concentrated fire of musketry that I have ever witnessed.” With his artillery knocked out and the Union vessels starting to get under way, Green decided to charge the boats, hoping to board one. As he was rallying his men, Green was killed by a Union shell that exploded nearby. With their leader killed and night falling, the Confederates withdrew.

From the Mississippi to Hampton Roads

Back at Grand Ecore, Selfridge was detailed to take Osage and Lexington and convoy the transports to Alexandria ahead of the gunboats, which he did without further incident. By April 27, the Union vessels were back at Alexandria, where they joined Banks’s Army. Now that the Union forces were united, they no longer were in danger of Confederate attack. However, Porter’s vessels now faced a bigger obstacle. Because the river had fallen again, there was only enough water rushing through the falls above Alexandria to allow the transports and smaller vessels to pass. Unless the water level of the falls could be raised, the heavier gunboats would be trapped.

Fortunately for them, Lt. Col. Joseph Bailey, an engineer officer with Banks’s Army, came to the rescue. Bailey, a former lumberman, proposed that Porter raise the water through the falls by building a dam at the lower falls. Porter agreed, and construction of the dam was finished on May 8. The following day, as the swift current tore away part of the dam, Osage and three other gunboats rushed through the damaged section. With all his vessels below the falls, Porter was able to continue his withdrawal. Several days later, the fleet reached the mouth of the Red River. Selfridge later called the Red River expedition “one of the most humiliating and disastrous that had to be recorded during the war.”

While returning to Vicksburg, Osage ran onto a shoal and could not be freed. Leaving his vessel, Selfridge went on to Vicksburg and took over command of the new ram Vindicator and the entire Fifth District of the Mississippi River. With Vindicator and a small squadron of ironclads and gunboats, Selfridge was supposed to protect river traffic and prevent any crossing by enemy troops from Vicksburg to the mouth of the Red River. As the summer wore on, Confederate activity along the Mississippi diminished to a point of inactivity. In the fall, Porter was ordered to take command of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Before leaving, he urged Selfridge to go with him. Selfridge agreed. At Hampton Roads he took command of the gunboat Huron, a screw steamer mounting an 11-inch pivot gun, a 30-pounder Parrott rifle, and several howitzers.

Attack on Fort Fisher

Near the end of November, Huron joined the Union blockading squadron off Wilmington, North Carolina. On December 24 and 25, she took part in the unsuccessful attack by Union land and sea forces on Fort Fisher. A second assault on the fort got under way the following month. Naval bombardment began on the morning of January 13, when the Union ironclads closed in on the fort and opened fire. After landing troops and stores, Huron joined in the bombardment. At nightfall, all the gunboats except the ironclads ceased firing and pulled back from the fort. The next morning, Huron joined the attack to dismount the guns on the landward side of the fort. Huron had her mainmast shot away and was hit in the hull by an 8-inch shell, which fortunately did not explode. Selfridge’s ship received two more hits before the bombardment ended.

The next morning, the whole fleet opened fire on Fort Fisher in preparation for a simultaneous assault by soldiers and sailors. Around noon, numerous small boats set out from the fleet carrying the naval party, which consisted of 1,600 sailors and 400 marines. As usual, Selfridge volunteered to go, and he took command of the third column. He described the subsequent advance: “We were opened upon in the front by the great mound battery, and in flank by the artillery of the half-moon battery, and by the fire of a thousand rifles. Though many dropped rapidly under this fire, the column never faltered, and when the angle where the two faces of the fort unite was reached the head halted to allow the rear to come up. This halt was fatal, for as the others came up they followed suit and lay down till the space between the parapet and the edge of the water was filled.”

Moving up to the front, close to the palisade of the fort, Selfridge found a grave situation. The sailors, he said, “were packed like sheep in a pen, while the enemy was crowding the ramparts not forty yards away, and shooting into them as fast as they could. Flesh and blood could not long endure being killed in this slaughter-pen, and the rear of the sailors broke, followed by the whole body, in spite of all the efforts to rally them.” Selfridge, along with some 60 other officers and men, huddled at the foot palisades until nightfall, when they withdrew. The Union captured Fort Fisher that night. “I will not go so far to say the army could not have stormed Fort Fisher without the diversion afforded by the naval assault,” wrote Selfridge, “but I do say our attack enabled them to get into the fort with far less loss than they would have otherwise have suffered.”

Selfridge After the War

When the war ended a few months later, Selfridge was assigned to the Naval Academy as an instructor. In 1869, he was promoted to commander and oversaw three surveys of Panama for a canal and explored deep into Colombia. For the next 24 years, he held a variety of positions both on land and at sea. As the commander of the European Squadron, he attended the coronation of the Russian czar, Nicholas II. On February 6, 1898, Selfridge retired as a rear admiral after 47 years of service. On February 4, 1924, two days shy of his 88th birthday, Selfridge died, one of the true naval heroes of the Civil War.

Selfridge was totally unimpressive. Cat believe a airbase north of Detroit was names after him

In comparison to many officers of rank in the Union forces who were politicos of marginal usefulness, Selfridge was quite accomplished. He kept his focus on the objective and, if not always successful, achieved more than many. Such is the nature of war and its participants.