By John Walker

After Adolf Hitler’s audacious invasion of Russia finally ground to a halt in December 1941 on the forested outskirts of Moscow, the exhausted German Army stabilized its winter front in a line running roughly from Leningrad in the north to Rostov in the south. The strain of the harsh winter campaign upon the ill-prepared Wehrmacht, as well as the severe strain placed on the Luftwaffe in its prolonged efforts to air-supply the army’s string of city-bastions along the front, was tremendous. But despite the horrendous losses they had suffered in the heavy fighting of 1941—a staggering 850,000 casualties—the Germans remained confident that they would master the Red Army once winter conditions no longer hindered their mobility.

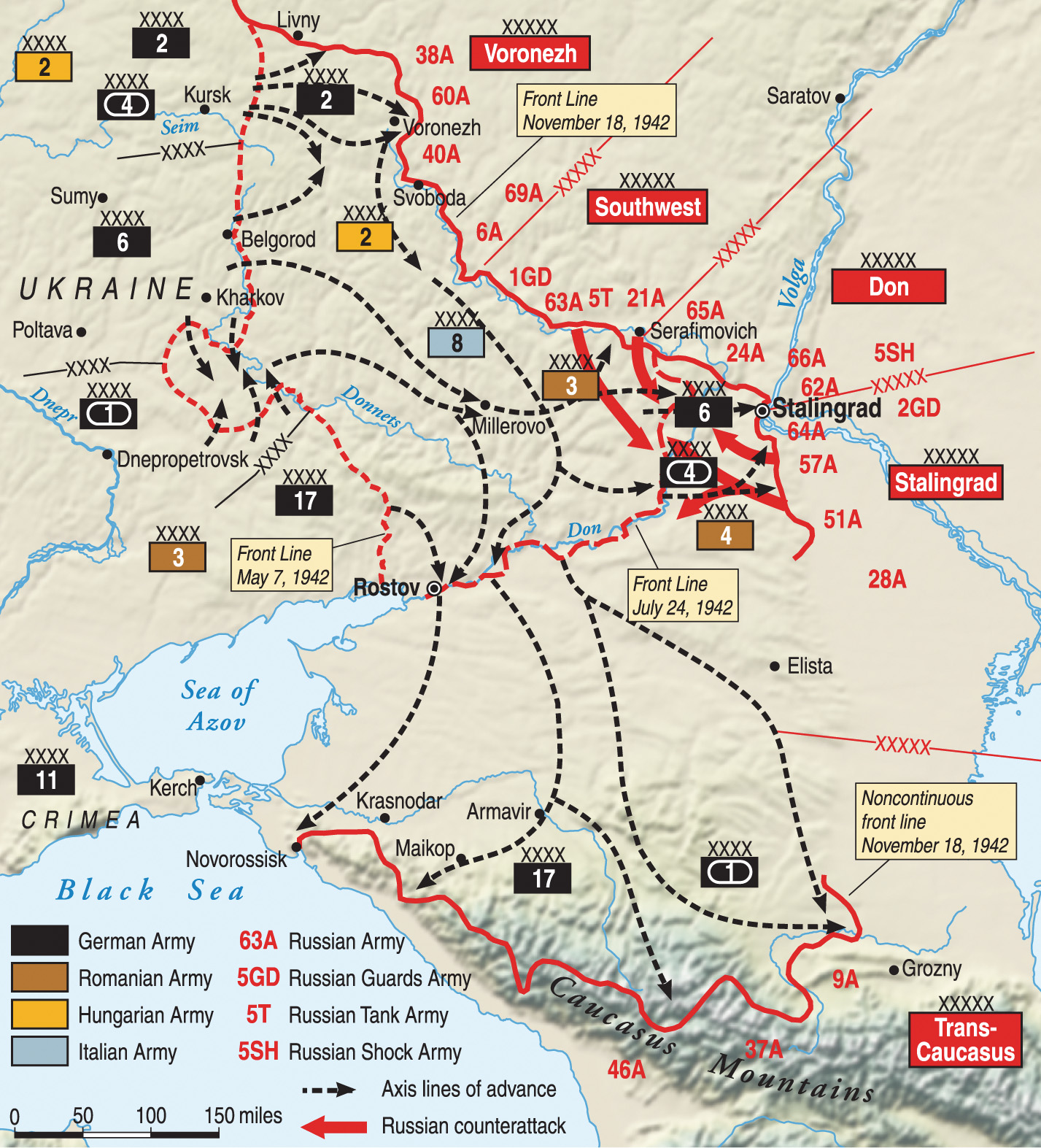

Hitler’s decision to resume offensive operations on the Eastern Front crystallized in the early months of 1942 after his economic advisers convinced him that Germany could not continue the war unless it captured vital oil supplies, wheat, and ore from Russia’s Caucasus region. Conceding that another all-out offensive was out of the question, Hitler limited the scope of the renewed offensive to just one flank, an idea that ran contrary to traditional German strategy. The Nazi armies in the center and left would hold their ground while the main thrust took place on the southern front near the Black Sea, a drive down the corridor between the Donetz and Don Rivers. After reaching the Don, German armies would turn south toward the Caucasus oil fields and advance east toward the great industrial city of Stalingrad, on the west bank of the Volga.

The capture of Stalingrad, a vital communications center that commanded the land bridge between the Volga and the Don and was a critical transport route between the Caspian Sea and northern Russia, was not part of Hitler’s original plan. The advance to the Volga by General Friedrich von Paulus’s Sixth Army was meant to provide strategic flank cover for the all-important advance into the Caucasus, where a successful offensive would complete the takeover of the Ukraine, interdict grain supplies from much of the Soviet bread basket, and cut off fuel to Joseph Stalin’s war machine.

Crushing the Soviet’s Southern Flank

The drive into southern Russia could only be carried out if the Germans drew heavily upon their allies—the Romanian Third and Fourth Armies, the Italian Eighth Army, the Hungarian Second Army, and the 369th Croatian Legion—to furnish most of the rearward cover for the flanks of the advance. The problem was that the foreign units were clearly inferior to their German counterparts. The potential for the offensive’s success improved considerably when a Russian Army numbering 640,000 men launched an overly ambitious offensive of its own on May 12, 1942, in the direction of Kharkov. The assault, which struck Paulus’s Sixth Army, absorbed great numbers of Russians reserves. Two complete Soviet armies, plus parts of two others, were cut to pieces, and by the end of May some 241,000 Red Army soldiers had been captured. The failure of the Soviet offensive meant that few reserves were available when the Germans launched their own sledgehammer blow, code-named Operation Blue, on June 28.

The German southern flank ran obliquely from the coast near Taganrog in the south, along the Donetz River north toward Kharkov and Kursk. It was a battlefront in echelon—the parts farthest back, on the left, were to move first, while the advance units on the right would wait for the left wing to come up before moving forward. On the German far right was the Seventeenth Army; next in line to its left and farther back, was the First Panzer Army. These two armies composed Field Marshal Wilhelm List’s Army Group A, destined to invade the Caucasus. On its left was Field Marshal Fedor von Bock’s Army Group B, which included Paulus’s Sixth Army and the Second Army, the latter consisting of the German Fourth Panzer Army and the Hungarian, Italian, and Romanian satellite armies. The two panzer armies were to deliver the decisive thrusts against the Russians’ most advanced positions, after which the infantry armies would follow.

A siege assault was launched against Sevastopol on June 7 as a preliminary to the main offensive. Despite fierce Soviet resistance, the fortress fell on July 4 and with it the whole of the Crimea, thus depriving the Russians of their chief naval base on the Black Sea. Meanwhile, the Germans forced the passage of the Donetz River, established a bridgehead on the north bank, and delivered a powerful armored stroke northward 40 miles to the city of Kupiansk, gaining invaluable flanking leverage to assist the easterly thrust of the main offensive, where heavy fighting raged for several days before the Fourth Panzer Army broke through between Kursk and Belgorod. After that the armored advance swept rapidly across a 100-mile stretch of plain to the Don River, near Voronezh. At Voronezh, three Soviet armies resisted fiercely against the onslaught of the combined forces of the Fourth and Seventeenth Panzer Armies and Paulus’s Sixth Army, believing the attack was a prelude to a German advance upon Moscow. To avoid encirclement, the three Soviet armies withdrew eastward in the direction of Stalingrad.

Hitler’s Eye on Stalingrad

Now Hitler split Army Group South into Groups A and B. After the Hungarian Second Army came up and relieved the Fourth Panzer Army, the Fourth then wheeled southeastward down the corridor between the Don and the Donetz, followed by Paulus’s army. The Sixth Army, the Fourth Panzer Army, and the Axis satellite armies then began their push east toward Stalingrad. As Army Group A pushed far into the Caucasus, its advance slowed as its supply lines grew overextended, and the two German army groups were not positioned to support one another due to the great distances involved. The Führer, obsessed and impatient to capture the Caucasus, had divided Operation Blue from a coherent, two-stage whole into two separate parts, changing the organization, timing, and sequence of the offensive, much to the chagrin of his top generals. Consistently underestimating the resilience of his Russian enemy, Hitler decided that the city of Stalingrad would have to be taken.

Marshal Andrei Yeremenko, commander of the Soviet southern front, searched for a strategy to keep the 700,000 soldiers in the Axis armies currently pushing toward Stalingrad from overwhelming South Russia’s last natural line of defense, the Volga. As the Germans neared the city in August 1942, the primary defense of the city fell to the Soviet Sixty-second Army. Yeremenko, needing a commander with the spirit and tenacity to rally the Russians and hold the Volga at all costs, chose Lt. Gen. Vasily Chuikov. Yeremenko immediately issued a terse directive to his army commanders—“Not a step back”—and instructed the Soviet secret police force, the dreaded NKVD, to shoot anyone who failed to comply. (Soviet authorities eventually executed 13,500 soldiers during the Stalingrad fighting, the equivalent of a full division.) Chuikov, convinced that he could not match the Wehrmacht’s firepower on the open steppes, laid plans for a street battle, picking out future strongpoints the enemy would be forced to pass en route to the Volga. He positioned his artillery in sectors where the Germans would be concentrated in the greatest numbers. The Soviet Sixty-fourth Army would defend Stalingrad’s southern sectors.

At the time, Stalingrad was the Soviet Union’s third-largest city, sprawling along a narrow band 20 miles long and five miles deep on the Volga riverfront. Although Soviet officials had considered evacuating children and nonessential citizens, some 600,000 of the city’s population of 850,000 still remained. A massive, sustained Luftwaffe carpet-bomb attack on August 23 set downtown Stalingrad aflame, reducing much of it to rubble and killing thousands of noncombatants. The reason so many citizens and refugees still remained on the west bank of the Volga was typical of the Soviet regime: the NKVD had commandeered almost all river craft for its own use while allotting low priority to the civil population.

Joseph Stalin, deciding that no panic would be allowed, refused to permit further evacuation of citizens across the Volga. This, he believed, would force his troops, especially locally raised militia, to defend the city even more desperately. Throughout the region, the civilian population was mobilized; all available men and women between 16 and 55 years of age—nearly 200,000—were formed into workers’ columns organized by their district Communist Party committees. As in Moscow the year before, women and older children were marched out and given long-handled shovels and baskets for digging antitank trenches over six feet deep in the sandy earth. While the women dug, Army sappers laid heavy antitank mines on the western side. Younger schoolchildren were put to work building earth walls around petroleum-storage tanks on the river. Those workers not directly involved in producing weapons were mobilized into special militia brigades. Some ammunition and rifles were distributed, but many men were able to arm themselves only after a comrade was killed.

The German Sixth Army Advances

The German Sixth Army, combined with two corps from the Fourth Panzer Army, was the largest formation in the Wehrmacht, with nearly a third of a million men. It pushed down the north side of the corridor between the Don and the Donetz rivers toward Stalingrad, supported by an armored drive farther south. At first Paulus made good progress. As the advance continued, however, its strength dwindled as more and more German divisions had to be detached to cover the ever-extending northern, or left, flank, which extended along the Don all the way back to Voronezh. Long, rapid marches in severe heat, as well as battle losses caused by stiffening Russian resistance, added to the German wastage.

On August 23, the Germans began the final stage of their advance upon Stalingrad. It took the form of a pincer attack by the Sixth Army from the northwest and the Fourth Panzer Army from the southwest. That night German mobile units reached the banks of the Volga, 30 miles above the city, and neared the bend of the Volga, 15 miles south. While Russian resistance kept the pincers from closing, German pressure on Stalingrad was intense. Attacks fell in endless succession, and the city became a hypnotic symbol for the Germans, and especially for Hitler who lost all sight of strategy and regard for the future. It was an obsession for which Germany would pay dearly.

A Battle of Supplies

Despite immense losses, the Soviets’ reserves of manpower remained far greater than the Germans’. As the end of summer neared, an increasing flow of equipment came from Soviet factories to the east as well as from American and British suppliers, and the volume of new divisions arriving from Asia also increased. The Germans, being the attackers, suffered proportionately higher losses, which they could ill afford. Back in Berlin, General Franz Halder, chief of the Army General Staff, attempted unsuccessfully to warn Hitler of the potential dangers his armies now faced. As winter approached, the German concentration at Stalingrad drained reserves from the flank-cover, itself already strained to the breaking point. The general’s warning to Hitler that it would be impossible to hold the line during the winter fell on deaf ears; all defensive considerations were subordinated to the aim of capturing Stalingrad.

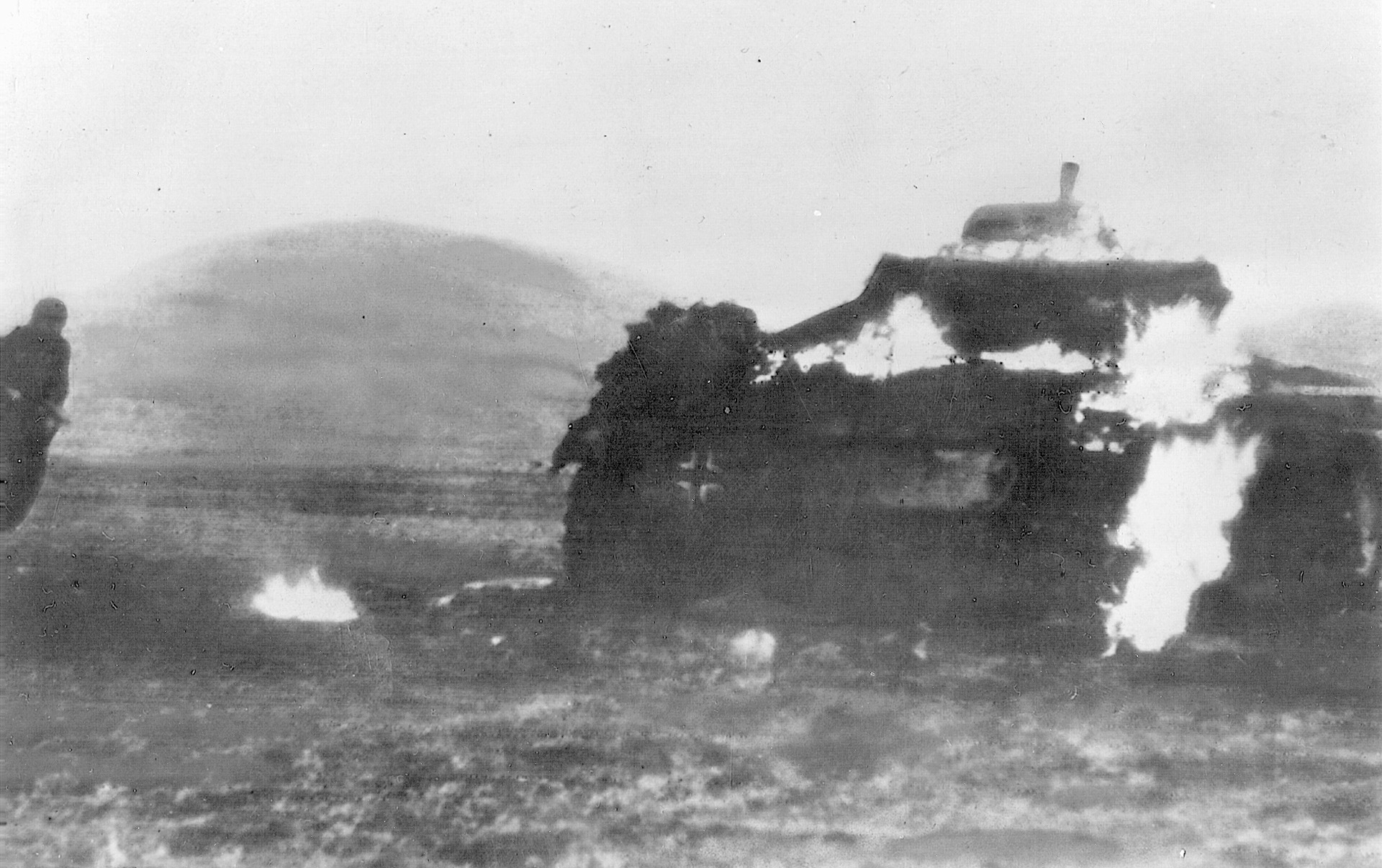

By September 1, the Soviet Sixty-second Army was fully engaged throughout the city. With the panzers unable to maneuver quickly through the debris-choked streets, the traditional German war of rapid movement ended. Germans gains began being measured in feet and yards, as the determined Russians fought viciously for every house and building that remained standing. When Stuka dive-bombers hammered Russian strongpoints, inflicting huge losses, surviving defenders merely found new places to hide in the rubble. Although they were suffering horrendous losses themselves, the Germans systematically leveled the city, block by block, and pressed relentlessly toward the Volga. While it was still capable of production, the Krasny Oktybar plant continued to produce its formidable Soviet T-34 tanks, driving them directly from the production line into battle crewed by the very workers who had built them.

Chuikov struggled to maintain contact with his beleaguered forces as they were driven back through the city. Many Russians continued fighting for weeks without orders, reinforcements, or supplies, inflicting heavy losses on their attackers before running out of food and ammunition and being wiped out themselves. As reinforcements and supplies finally began flowing toward Stalingrad from every region of the Soviet Union, the struggle for the city became a test of wills between Stalin and Hitler. Ample matériel was available to the Soviets on the east side of the Volga, but with the Germans in control of the river to the north and south, everything had to be funneled through a single ferry landing into central Stalingrad. The east bank of the Volga became a vast marshaling yard for men and materials as well as the location of a huge field hospital and a launching point for batteries of newly developed Katyusha rockets. Dubbed “Stalin’s organs,” the truck-launched, 130mm rockets fired 16 at a time. Nearly five feet in length, the missiles were deadly accurate, and the horrific screech they emitted from launch to impact became a considerable psychological weapon as they rained down day and night on German-held sectors of the city.

The Soviet Air Force had finally been supplied with modern aircraft such as the Yak 1 and began to contest the Luftwaffe for air superiority over the city. For the first time in the war, German ground forces began receiving the same punishment from the air that the Luftwaffe had been inflicting upon their enemies. With bombs, rockets, and shells pouring into Stalingrad around the clock, the city cast a macabre glow that could be seen from 30 miles away at night. The gruesome pall of smoke and dust that churned up from the embattled city panicked many Russian reinforcements being ferried into the city from the Volga’s east bank. Hoping to escape the fighting, hundreds jumped from the shuttle boats into the Volga’s frigid waters, only to be shot by NKVD officers.

Both Paulus and Chuikov had ample forces at their disposal, but the Germans’ narrow approaches to the city and the Russians’ bottleneck at the river crossing forced both commanders to feed their units into battle piecemeal. The Germans slowly gained ground, at an enormous cost in blood, while Chuikov’s delaying tactics worked well, but at a tremendous cost of Russian casualties. Chuikov worked to funnel and fragment German massed attacks with “breakwaters,” fortified buildings manned by infantrymen armed with machine guns and antitank weapons to deflect attackers into channels where camouflaged T-34 tanks and antitank guns waited, half buried in the rubble.

90 Percent of the City in German Hands

The battle was being closely monitored in Berlin, where Halder repeatedly expressed grave concerns to Hitler about the exposed German left flank. With no end in sight, Hitler in mid-October dismissed Halder, replacing him with General Kurt Zeitzler, a timid yes-man, and announced prematurely to the German people that victory in the East was almost at hand. In Stalingrad, however, although the Soviet Sixty-second Army was being forced back into several small sectors of ground near the west bank of the Volga, the battle itself was far from over.

With German infantry and panzers in control of 90 percent of the city, Chuikov’s troops struggled to hold onto their precarious footholds. Prolonged street fighting had reduced the city almost entirely to rubble, and the smell of charred buildings and the sickly stench of decaying corpses was overpowering. Chuikov instructed his troops to close with the enemy and seek hand-to-hand combat at every opportunity, and the Wehrmacht was unable to call in artillery or air strikes for fear of hitting their own men. The battle became a vicious war of attrition involving hundreds of brutal, small-unit actions. If Paulus could bleed the Russian Army to death before the Volga froze over, he could take the city before the onset of winter. But Soviet artillery, snipers, and booby traps had already sent German casualty lists soaring far beyond what they had anticipated. If the German losses were heavy, Russian casualties were staggering: as many as 80,000 Soviet soldiers had been killed in action by the middle of October 1942. The combined toll on Russian civilians, Red Army soldiers, and Axis forces had already reached a quarter of a million people.

Pavlov’s House

German infantry units now controlled the summit of Mamaev Kurgan, also called the Tartar Mound, a towering hill in central Stalingrad, as well as the southern suburbs, and had broken through to the Volga north of the city. With his command split, Chuikov held downtown Stalingrad, the all-important ferry landing, the Barrikady Metal Works, and much of the Krasny Oktybar plant, all of which were reduced to rubble. At one point, German ground forces pushed to within 200 yards of Chuikov’s command bunker and were seemingly on the verge of victory, but isolated Russian strongholds thwarted the final conquest of the city. A platoon of the 42nd Guards took possession of a three-story downtown building that commanded all approaches to the Volga, turning it into an almost-impenetrable fortress bristling with machine-gun nests and snipers. With all its officers killed or incapacitated, Sergeant Yakov Pavlov assumed command of the platoon and held the building for 59 days before being relieved. He had discovered early on that an antitank rifle mounted on the rooftop could destroy German panzers with impunity, since a tank approaching the building could not elevate its barrel sufficiently to reach the rooftop.

By early September, the Sixth Army found itself trapped at the edge of a huge salient, with few reserves, fighting an intense battle of attrition and dependent upon a single railway line that crossed the Don at Kalach, 60 miles from the Soviet lines. Paulus had no illusions about the prospects of maintaining his army through the winter in a devastated city still contested by a stubborn enemy. By this time, he had already committed eight divisions to the fighting and 11 more manned nearly 130 miles of front stretching across various river bends and over the sprawling Russian steppes.

To bring an end to the exhausting battle, Paulus called in several battalions of elite pioneer combat engineers, experts in demolition and street fighting, and used them to spearhead a last major attempt to capture Stalingrad. In a furious assault on the burrowing Russians, the German engineers poured gasoline into sewers and ignited them, ripped up floorboards, and threw satchel charges into cellars to root out defenders. Paulus followed on November 11 with an attack by five divisions into the factory district. The ensuing breach in the Russian lines was expanded, and Chuikov’s command was split in two. Still the Russians held on, despite appalling losses. Spent and exhausted, the Germans regrouped while Paulus pondered his next move.

Ice had begun forming on the Volga, and by November 14 all boat traffic ceased—the river was impassable. Efforts were made to air-drop supplies to the Sixty-second Army, but with the Soviet foothold reduced to such a narrow margin, most of the matériel fell into German hands. While Chuikov fought to hold the city until relief arrived, German reconnaissance planes and intelligence reports began detecting signs of a huge Soviet buildup northwest of Stalingrad. The exposed left flank that had worried Halder was showing unmistakable signs of becoming a ripe target for a massive Russian counterattack.

Operation Uranus: Death Blow to the Sixth Army

Back in Berlin, Hitler was made aware of the Soviet buildup, and his response was typical: remain on the offensive. On November 17 he sent a dispatch to Paulus urging him to quickly complete the conquest of the city. Paulus circulated the Führer’s exhortation to his unit commanders, but they never had a chance to act on it. On the morning of November 19, the rumble of heavy artillery to the northwest could be heard rolling across the steppes. The deafening explosions were the opening salvos of a well-prepared, overwhelming Soviet counterattack, one that would seal the fate of Paulus and his men.

While Chuikov had been fighting for time, Stalin, General Georgi Zhukov, and Soviet Supreme General Staff chief General Alexander Vasilevsky had assembled the forces necessary to close an impenetrable iron ring around Stalingrad. Massive Soviet forces had been clandestinely deployed in the steppes north and south of the city. To the north was the Southwest Front under General Nikolai Vatutin. Next was the Don Front under General Konstantin Rokossovsky, and to the south of the city was the Southeast Front under Andrei Yeremenko. While just enough men and supplies were funneled to Chuikov to enable him to hold the city, over a million fresh troops, 1,500 tanks, 2,500 big guns, and three air armies deployed along a front almost 150 miles wide. The Soviets intended to attack the German flanks at their two weakest points—100 miles west of Stalingrad and 100 miles south of it—in sectors held by the Romanian Third and Fourth Armies.

On November 19, the Red Army unleashed Operation Uranus in a blinding snowstorm. The attacking Soviet units on Vatutin’s front—three complete armies—swept southeast from the Serafimovich bridgehead, shattering the Romanian Third Army along a 40-mile-wide stretch of the Don on Paulus’s northern flank. The next morning, a second Soviet offensive—two complete armies of Yeremenko’s Southeast Front—got under way from the south of the city, advancing northwestward against positions held by the Romanian Fourth Army.

Under the sudden pressure of the massive Russian artillery and advancing tank columns, the Romanian forces collapsed almost immediately. The two Soviet fronts raced west in a huge pincer movement and met four days later near the town of Kalach, sealing the ring around Stalingrad. Meanwhile, troops of Rokossovsky’s Don Front had spread over the country west of the Don in a multipronged drive southward into the Don-Donetz corridor, linking up on the Chui River with the left pincer thrusting in from Kalach. The movement dropped an iron curtain across the most direct routes that any relieving German forces might use to come to the aid of Paulus and his army.

As Paulus flew to a new command post to escape the onrushing Soviet tide, he saw for himself the extent of the rout and knew that it would be a matter of only days before the Sixth Army was completely surrounded and cut off. He radioed headquarters, urgently requesting permission to withdraw his forces 100 miles to the west before the Russian ring around his troops became unbreakable. Hitler dismissed the request and ordered Paulus to assume a “hedgehog” defense. The Sixth Army slowly ran out of time while Hitler moved his own headquarters to East Prussia to get a better look. In the meantime, he named Field Marshal Erich von Manstein head of the newly formed Army Group Don, which left Paulus under Manstein’s operational control but did not materially affect the situation.

“A Prussian General Does Not Mutiny”

Hitler’s decision to hold Paulus in place left no alternative but to attempt to sustain the Sixth Army from the air. Paulus, his army trapped within a tightening ring of Soviet armor, informed Hitler that he had only six days’ worth of food remaining for his men. Morale, said Paulus, remained high, since the men believed they would be saved by other German armies. The Germans dubbed their position der Kessel—the kettle. General Wolfram von Richthofen, commanding Luftflotte 4, tried to fulfill Hitler’s promise to sustain Paulus by air, but from the outset he realized the task was hopeless. Paulus needed a minimum of 500 tons of supplies daily just to sustain his army in a defensive posture and prolong the Soviet effort to liquidate the pocket.

When the Russians captured the Kalach Bridge on November 23, Paulus’s army and a corps of the Fourth Panzer Army were sealed inside a pocket some 30 by 40 miles wide, the nearest German reinforcements more than 40 miles away. After expanding the corridor separating the Sixth Army and the rest of the German forces to a width of over 100 miles, the Russians moved 60 divisions and 1,000 tanks into position to attack Paulus’s army. Fierce fighting began to shrink the pocket. Although convinced that Hitler’s orders would lead to the total destruction of his army, Paulus remained intent upon obeying the Führer, saying simply, “A Prussian general does not mutiny.”

Despite Richthofen’s efforts, the airlift never had a chance for success. The shortage of aircraft, horrible flying weather, and the sheer distances involved doomed it from the outset. Pilot fatigue, improperly trained air crews, icy buildup, and Soviet fighters left a trail of downed Luftwaffe aircraft strewn across the steppes on the approaches to Stalingrad. As the airlift sputtered out, Paulus cut his troops’ rations in an effort to conserve food. Ammunition stockpiles were steadily depleted, and the Sixth Army’s capacity to resist began to dwindle accordingly. Orders went out to return fire only when essential and then to take only “sure shots.”

The Sixth Army’s Christmas Dinner

Although Hitler added to the confusion by issuing orders that were ever more absurd and self-contradictory, German morale received a boost when word spread that the Führer had ordered Manstein to mount a relief operation and open a supply corridor to Paulus by punching a hole in the encirclement. Operation Winter Storm, launched on December 16, proved as hopeless as the airlift. Manstein’s division-size force of panzers was inadequate to pierce the ring of Soviet artillery and armor. Meanwhile, the Sixth Army’s fuel and ammunition situation had deteriorated to the point that most heavy equipment, trucks, and armor would have to be abandoned if a breakout was attempted. Hitler steadfastly refused to consider the withdrawal of Sixth Army from Stalingrad, saying that without their heavy guns and armor such a retreat would have a “Napoleonic ending.” In this, at least, he would prove correct.

As Christmas 1942 approached, the Sixth Army’s situation became increasingly desperate. The relief column had retreated, supplies arriving by air were diminishing, and starvation had begun to thin the ranks. As the full impact of the harsh Russian winter set in, the trapped German Army rapidly ran out of heating fuel and medical supplies, and thousands of the Army’s remaining effectives began suffering the effects of frostbite, malnutrition, and disease. With no fodder for their horses, the Germans began slaughtering the animals for food, and on Christmas Eve Paulus ordered the last of the horses killed to provide a makeshift Christmas dinner for his men. The following day, he ordered yet another cut in the men’s rations; the food allotment for each man was now a bowl of thin soup and 100 grams of bread per day. German doctors, coping with an increasing number of wounded men and diminishing stocks of medicine with which to treat them, were forced to give first priority to wounded soldiers who stood the best chance of recovering and being returned to battle. It was a triage of the damned.

Closing Off the Stalingrad Pocket

Rokossovsky and Yeremenko, meanwhile, tightened the noose around the Germans daily, shrinking the perimeter Paulus had to defend. Additional Soviet advances swept the Axis flank defenders—Romanians, Italians, and Hungarians—almost entirely out of the Don-Donetz corridor, threatening the rear of the German forces on the lower Don and in the Caucasus. Hitler at last realized the inevitability of a disaster even greater than that of the Stalingrad encirclement. The decision was made to withdraw from the Caucasus just in time for Army Group B to escape being cut off itself. That withdrawal made it clear to the world that the German tide of conquest was on the ebb.

On January 10, 1943, Rokossovsky issued a call for Paulus to surrender, promising food and medical treatment for all the defenders and allowing German officers to retain their badges of rank and decorations. Paulus radioed Hitler, asking permission to surrender and thus save the lives of his remaining men, but again the Führer refused, ordering Paulus to stand and fight where he was—to the last man and the last bullet, if need be. Hitler dispatched Luftwaffe Field Marshal Erhard Milch to the front to revive the flagging airlift effort, but not even Milch could figure out a way to stanch the bleeding caused by worsening winter weather and the dominance of Soviet fighters controlling the skies around Stalingrad.

As the attempt at resupply by air faded away, the proud army that Paulus had led to the edge of the Volga disintegrated. The elite soldiers of the German Sixth Army were now a tattered collection of emaciated, walking skeletons. With starvation, disease, and despair stalking the Army, desertions, unauthorized surrenders, and an occasional local mutiny diminished the Sixth Army’s capacity for organized resistance. In the meantime, the Red Army relentlessly closed the ring around the city.

“The Troops are Out of Ammunition and Food”

His demand for surrender rebuffed, Rokossovsky ramped up the pressure on the Stalingrad pocket. On January 10, the Soviets attacked the city with 47 divisions, and by mid-January the remnant of Paulus’s command held an area just 10 miles square. Staff officers at Army headquarters in Berlin, tacitly admitting to themselves that Sixth Army was lost, tried to salvage what they could of its technicians and specialists while abandoning the rank and file to their fates. They stepped up evacuation of officers with rare skills and ability, giving them priority on flights out of the pocket ahead of the wounded. General Hans Hube, commander of the 16th Panzer Division, was one such officer. After being ordered to abandon his command and fly out of Stalingrad, Hube refused, only to be evacuated forcibly by a squad of Gestapo agents sent to the city. By the end of January, the starved, frozen, and exhausted survivors of the Sixth Army were on the verge of collapse.

Paulus dispatched an aide to speak directly to the Führer, hoping that a firsthand account of the dire situation might change Hitler’s mind. Hitler was unmoved, replying that the Sixth Army’s ordeal was tying down Soviet forces that might otherwise prevent the planned evacuation of the German Army Group then in the Caucasus. German airlift operations struggled on until January 24. Immediately after two Ju-52s managed to lumber off the runway at Pitomnik airfield, a Soviet T-34 tank broke through the outer defense ring of the airfield and began shooting up the control tower and makeshift airport facilities. More tanks and Soviet infantry followed, and the airfield fell into Soviet hands, bringing the German airlift to an abrupt and final halt.

With all hope of relief or rescue now gone, Paulus radioed a message to Hitler: “The troops are out of ammunition and food, effective command is no longer possible. There are 18,000 wounded without any supplies, dressings or drugs. Further defense senseless. Collapse inevitable. Army requests permission to surrender in order to save the lives of the remaining troops.” Hitler gave the same response he had made to all similar requests: “Surrender is forbidden. Sixth Army will hold their positions to the last man and last round and by their heroic resistance make an unforgettable contribution towards the establishment of a defensive front and the salvation of the Western world.”

In an unprecedented, if cynical, show of generosity, Hitler gave promotions to dozens of senior officers of the Sixth Army, most notably a field marshal’s baton for Paulus. In the entire history of the German Army, Hitler noted, no field marshal had ever surrendered or been taken alive. The implication was clear, but Paulus had no intention of throwing himself onto his own funeral pyre. A few days later, Soviet forces closed in on his command post, a cellar in the bombed-out ruins of a store in downtown Stalingrad. On the verge of collapse, dirty and unshaven, Paulus surrendered, and on February 2 the last German resistance in Stalingrad ceased. Of the nearly 350,000 soldiers who had followed Paulus to Stalingrad, barely 91,000 survived to surrender to the Soviets.

Three-Days of Mourning for the Sixth Army

After Stalin announced to the world the news of Paulus’s surrender and the Soviet victory at Stalingrad, a sense of foreboding fell over the Third Reich. The German people were finally informed of the loss of the German Sixth Army, and a three-day mourning period went into effect. While Paulus relaxed in a warm suburb of Moscow, the soldiers of the Sixth Army who had been promised food and shelter were not so fortunate. The Russians put 20,000 of them to work rebuilding the destroyed city, and the rest were dispatched to POW camps scattered from Siberia to central Asia. Many died shortly after the surrender from a typhus epidemic brought on by lice and the unsanitary conditions experienced during the battle. Many more would perish from malnutrition, disease, and neglect in the various Soviet prison camps. Of the 91,000 men who surrendered with Paulus, only 5,000 survived to eventually return to Germany in 1955.

For their role in the great Soviet victory, Chuikov and his Sixty-second Army received the highest honors the Red Army could bestow upon its soldiers. It was renamed the 8th Guards Army for the heroic defense of the city, and Chuikov led his men on a march across Europe that ultimately reached Berlin. His troops had the honor of capturing the Reichstag and planting the hammer and sickle atop the building in the fallen capital of the Third Reich.

The Psychological Turning Point of World War II

From the Soviet perspective, the struggle for Stalingrad carried implications far beyond its borders. It defined the major, psychological turning point of World War II in Europe. By halting the advance of one of Germany’s elite armies and ultimately defeating it, the Russians proved that the Nazis were not invincible, and in doing so they gained the confidence and skills they would need to ultimately defeat Germany. Conversely, the disaster at Stalingrad shattered the myth of Hitler’s infallibility among the Germans themselves. Indeed, the path to the Soviet Union’s rise to the status of a true superpower began on the banks of the Volga River.

The monumental scale of the battle lived on in the ruins of the shattered city. Although a panel of the Supreme Soviet determined that it would be easier to abandon the city and build a new one elsewhere, Stalin’s ego and determination brought about the ultimate reconstruction of the city. But buried among the ruins was the horrendous price the Russians had paid for their victory. It will never be known how many people died at Stalingrad. Some postwar estimates claim that Chuikov lost over a million soldiers in his effort to hold the city, but that figure is almost certainly exaggerated. Still, the loss of life was appalling.

The casualty figures for the German Sixth Army, the Fourth Panzer Army, and their Axis auxiliaries that supported the march to the Volga were staggering. The Germans lost about 400,000 men; the Italians, Hungarians, and Romanians about 120,000 each. According to archival figures, the Red Army suffered a total of 1,129,619 total casualties—478,741 killed and missing and 650,878 wounded—in the greater Stalingrad area. In the city itself, 750,000 Russians were killed, wounded, or captured. The most horrendous toll fell on the city’s civilian inhabitants. Of Stalingrad’s estimated 850,000 residents in 1940, only 1,500 citizens remained in the pile of rubble that once was Stalingrad.

Please acknowledge Chief of Staff Nikolai I Krylov for his role in the battle. He had a vital role and is not recognized as he should be.

In Russia and even in much Western literature about World War Two there is still a widespread belief that the conflict in the east was the ‘real war’ and that the Anglo American effort was peripheral. Central to this belief are the pivotal events surrounding Stalingrad. There is only one problem; that belief is misleading. While the Eastern Front occupied three quarters of the manpower in the German Army and incurred most of the casualties, it did not occupy most of the German war economy. Even in 1942 and prior to Stalingrad more than half the German war effort was being devoted to the west and this only increased in later years. Many wonder how this was even possible when the bulk of military manpower was committed to the east? In 1942 half of all German military expenditure was on the Luftwaffe and half of that was committed to Northern France, the Mediterranean and Norway. More than thirty percent was devoted to U Boat production, construction of the Atlantic Wall and the protected U Boat enclosures in Western France, plus, the building up of anti aircraft defenses against the growing Anglo American Bomber offensive. Less than ten percent was expended on tank production. That is why Russian tank production overwhelmed German tank production, that is why the Russian air force was able to push back against the Luftwaffe and that is why the German rescue effort at Stalingrad failed. In summary, Germany’s military ambitions in the East failed because most of the war production was being diverted west. This made the failure at Stalingrad inevitable. This economic aspect to the war is rarely discussed but gives some context to the events that transpired.

“General Wolfram von Richthofen, commanding Luftflotte 4, tried to fulfill Hitler’s promise to sustain Paulus by air….”

Not a word about Goering, who assured Hitler — another egocentric and absurd, total failure on his part, like his promise that no Allied bomb would ever fall on Berlin — to supply the Stalingrad defense by air?