By Kelly Bell

Darwin, Australia, was hot even though it was mid-winter. On the afternoon of July 12, 1942, four newly deployed pilots of the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) 49th Fighter Group climbed into the cockpits of their Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk single-engine fighters and lifted off for a training mission. The youngsters were 1st Lt. J.B. “Jack” Donalson and 2nd Lts. John Sauber, Richard Taylor, and George Preddy, Jr.

Japanese air raids had recently plagued the area, and this quartet of airmen was being groomed to do something about it. Preddy and Taylor peeled off and played the role of Imperial Japanese bombers while Donalson and Sauber rehearsed their intercepting skills by making dummy attacks on their comrades, but something went wrong. The sun may have blinded Sauber or, rookie that he was, he may simply have misjudged the distance between his and Preddy’s planes. He waited too long to pull up and crashed into Preddy’s tail at 12,000 feet, sending both machines tumbling.

Preddy managed to bail out at the last moment, but Sauber’s cockpit was apparently jammed shut. He was killed on impact. Preddy’s chute cracked open seconds before he came down in a tall gum tree that shredded the parachute and sent him crashing through the branches to the ground.

Lieutenant Clay Tice happened to be passing by in his own P-40 and saw the mishap. He radioed its coordinates to the nearby airfield, and ground crewmen Lucien Hubbard and Bill Irving jumped in a truck and raced to the critically injured Preddy’s aid. The young man had a broken leg and deep gashes in his shoulder and hip. He was bleeding as the mechanics rushed him to the infirmary. After a long session in the operating room, the base surgeon reported that if not for his comrades’ prompt response Preddy would quickly have bled to death. It would not be the last time he would be victimized by his own side’s mistakes.

Following a lengthy recovery, Preddy was transferred to the 352nd Fighter Group, which the liner Queen Elizabeth delivered to Scotland’s Firth of Clyde on July 5, 1943. Despite still being green he was one of the most experienced men in the outfit. Virtually all the other pilots were fresh from flight school, and Preddy’s modest experience meant little because he had to forget his work with the P-40 and begin learning to fly the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter. After being indisposed a full year, he was chafing for action and already knew what he was going to call his new warplane. A habitual gambler, he believed yelling “Cripes A’ Mighty!” brought him luck when he tossed the dice. This crap game cry would be painted on every machine he flew.

First Victories for Preddy

Assigned to Bodney airfield, the 352nd started out flying cover for ammunition- and fuel-bereft Thunderbolts of the 56th and 353rd Fighter Groups as they returned from escort missions. This gave Preddy and his buddies little action, but the Allied strategic bombing offensive was just reaching a serious and costly stage.

October 14, 1943 is still known as “Black Thursday.” It was the day Preddy was among 196 frustrated Thunderbolt pilots whose near-empty fuel tanks forced them to turn back for Britain just as swarms of experienced, opportunistic Luftwaffe airmen tore into Eighth Air Force bomber formations approaching the Schweinfurt ball bearing works. The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers fell like snowflakes, making it clear the fuel-guzzling Thunderbolt was not suitable as a long-range escort fighter. For the time being, though, it was the best plane available.

The autumn of 1943 was pivotal in the air war over Western Europe as the Allies tried to pour bombers into the skies over the Third Reich faster than the Germans could shoot them down. Despite its high kill rate versus the big birds, however, the Luftwaffe was also suffering mightily. On December 1, Preddy got his first victory when he flamed a German Messerschmitt Me-109 fighter attacking a bomber returning from a raid on Solingen. Cripes A’Mighty’s eight .50-caliber machine guns virtually disintegrated the interceptor. Preddy’s 487th Fighter Squadron was the only one from the 352nd Group to score any kills that day, but many more were coming.

On December 22, the group lifted off to meet 574 bombers returning from immolating the marshaling yards in Munster and Onabruck. Preddy’s wingman was a talented young concert pianist named Richard R. Grow. The pair became separated from the rest of their flight when they plunged into a massive, confused dogfight in a huge cloud bank just east of the Zuider Zee. Emerging from the bottom of the cumulus they found themselves alone and began climbing to rejoin the bomber formation.

Entering a break in the clouds they spied a gaggle of 16 Messerschmidts attacking a smoking B-24. Preddy torched the German closest to the bomber and then plunged back into the overcast. Surprisingly, the rest of the interceptors turned away from the bomber and took off after the pair of Thunderbolts. The 13,000-pound Cripes A’Mighty easily outdove its pursuers, but they evidently did catch up with Grow. He never made it out of the clouds. Still, the crippled Liberator, Lizzie, made it home. Preddy was recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross for this episode but instead received America’s third highest decoration, the Silver Star.

The Risky Sea Rescue of Preddy

After Christmas massive ice storms bracketed the European Continent, aborting major air operations by both sides. On January 29, 1944, the weather cleared long enough for a shoal of 800 bombers to target Frankfurt-an-der-Main’s industrial complexes. When the 487th flew out to meet the returning formations, Preddy shot down an FW-190 over the French coast but passed too low over a flak pit and suffered a direct hit. He managed to coax the smoking Cripes A’Mighty up to 5,000 feet, but then the heavy plane began to lose altitude.

Reaching 2,000 feet, Preddy realized he would soon be too low to bail out, so he jumped and inflated his pressurized dinghy. His wingman, 1st Lt. William Whisner, risked running out of fuel by circling over Preddy and repeatedly radioing his coordinates until air-sea rescue could triangulate the position. A Royal Air Force flying boat arrived, but in the rough, freezing seas it ran over Preddy, severely bruising and almost drowning him. When the British pilot tried to take off, a wave hit the plane and broke off one of its pontoons. This made it impossible to get airborne in the huge swells, so the crew had to call for a Royal Navy launch to tow the crippled flying boat to port. The Englishmen had some contraband brandy aboard, however, and by the time the launch arrived Preddy and his rescuers were well thawed.

Falling in Love with the P-51 Mustang

Soon after his frosty baptism, Preddy and the 352nd began switching over to the new North American P-51 Mustang fighter and immediately fell in love with it. On April 22, the group flew a protracted escort mission for bombers attacking Hamm, Sost, Bonn, and Koblenz. Between bombing runs Preddy and two other pilots strafed the Luftwaffe airfield at Stade. They simultaneously opened their guns on a Junkers Ju-88 twin-engine bomber that had just taken off, tearing it apart. After making their report back at Bodney, the three were amused to be awarded a .33 kill credit apiece.

On April 30, Preddy, newly promoted to major, accepted combat with an FW-190 at 17,000 feet over Clermont, France, quickly flaming his opponent. From this point his kill total mounted steadily as he and Cripes A’ Mighty II became better acquainted. It came at a good time.

Six Kills with a Hangover

The Normandy invasion was in the offing, and the USAAF was concentrating on neutralizing Luftwaffe opposition in northwestern Europe. From April 30 until the D-Day landings on June 6, Preddy downed another 4.5 planes. By this point he had already completed a standard 200-hour tour of duty along with two 50-hour extensions. He could have returned home but was thinking only of what he could do to end the war. He acquired a third 50-hour extension. As northern France convulsed with the massive land battles of the summer of 1944, he scored nine kills from June 12 to August 5. His greatest adventure was at hand.

After returning to base on the evening of August 5, he read the meteorologist report forecasting widespread thunderstorms for the next day, and announcing no flights were scheduled. It was the night of the 352nd’s war bond drive party, and the combat-weary Preddy had a merry time until almost dawn. During the night’s revelry nobody noticed the skies clearing. The young hero went staggering off to bed just before daybreak. Twenty minutes later an aide woke him with the news that a bombing raid had been scheduled, and he was slated as flight leader for the escort elements.

During the preflight briefing, Preddy was so drunk he fell off the podium. For want of anything better, several pilots propped him in a chair and held an oxygen mask over his nose as he slowly and somewhat sobered. After he got to his feet, his comrades threw a glass of ice water in his face, slapped him with a wet towel, and led him to his plane. After they helped him into the cockpit he lifted off normally and led his squadron on a maximum effort mission to Berlin. The weather turned out to be beautiful with cloudless skies and unlimited visibility. The Luftwaffe was also up in force.

Before the Americans reached their target, 30 German Me-109s assailed the B-17s Preddy’s squadron was escorting but did not seem to notice the accompanying Mustangs. Leading an attack from astern, Preddy opened on an interceptor and apparently killed the pilot. The blazing plane spun earthward, and no parachute blossomed. Preddy next sent a flurry of bullets into another 109’s port wing root, igniting it as its pilot bailed out. As the Mustang pilots waded deeper into the enemy formation, picking off one German plane after another, those in front continued to fire on the bombers, seemingly oblivious to the trailing menace.

Preddy downed another two Me-109s before the remaining interceptors suddenly realized they were under attack. When these survivors dove to escape, the Americans followed. Preddy torched his fifth victim of this battle, and as the flock of fighters descended to just 5,000 feet he latched onto the tail of yet another. The German yanked his plane to the left in an attempt to get on his pursuer’s tail, but Preddy reacted too quickly, also shearing left and passing over the Messerschmitt. Using the speed he had built up in his dive, he dropped astern of the Me-109 and opened fire from close range. This pilot, too, bailed out.

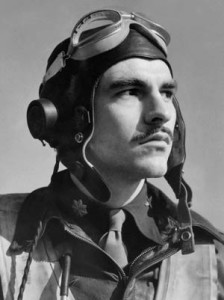

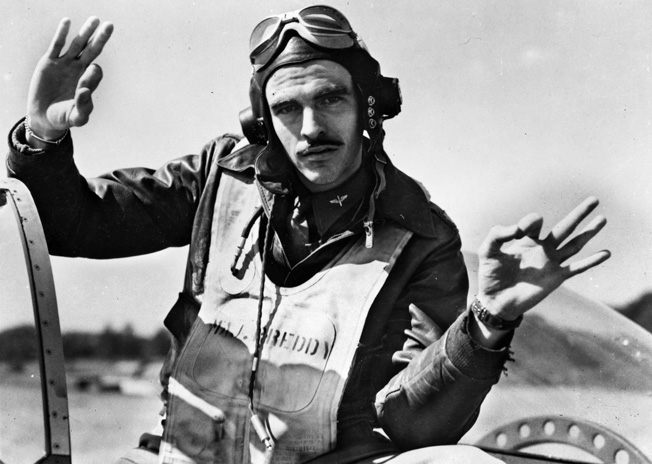

After Preddy landed back at Bodney, combat photographer 1st Lt. George Arnold photographed the pale, sick-looking hero climbing from Cripes A’MightyII’s vomit spattered cockpit. Not bothering to report his kills, Preddy let his gun camera footage and comrades speak for him. Over the next few days the press descended in droves on the airfield as Major George Preddy, Jr., sleek and handsome as a movie star, became the toast of Allied Europe. It all seemed to embarrass him. His commander, Lt. Col. John C. Meyer, recommended him for the Medal of Honor for his six-kill flight and was angry when, on August 12, Brig. Gen. Edward H. Anderson instead pinned a Distinguished Flying Cross on Preddy’s tunic. Typically, the young major did not seem to care.

“Reverend, I Must Go Back”

Combining aerial, ground, and partial kills, Preddy now had 31 victories, and his third 50-hour combat extension had expired. This time he did consent to return home on leave and would never again fly Cripes A’Mighty II. The 352nd’s senior officers erroneously assumed he was leaving for good and assigned the plane to another pilot.

While home in Greensboro, North Carolina, Preddy told his pastor, “Reverend, I must go back.” There was little room for ego in this selfless young soldier. Awards, medals, and adulation did not interest him. All he really cared about was bringing the war to a victorious conclusion, and he figured this would happen sooner if he were flying combat missions.

Preddy spent seven weeks in the States before securing yet another 50-hour extension. When he returned to England he was given command of the 352nd Group’s 328th Squadron. He was also presented with a brand-new P-51D-15NA fighter that he refused to fly until the name Cripes A’ Mighty III was painted on its fuselage. Preddy was placed in command of the 328th Squadron because it had the worst kill tally in the group, and he was expected to do something about this. He did his best in the time he had remaining.

On November 2, he led his pilots on a mission to guard bombers headed for Merseburg. When he spied a number of suspicious contrails at 33,000 feet, he realized a flight of interceptors had leveled off at their altitude ceiling in hopes of attacking the bombers from above. The Mustangs could fly as high as the Messerschmidts, though, and Preddy led his formation to the Germans’ rear and was first to attack. Although this was the first time he had ever looked through the new British-designed K-14 gunsight, he used it expertly, quickly downing an Me-109 as he and his men scattered the enemy formation before it could molest the bombers.

The next day he shot down an FW-190. This was his last victory for more than a month as the thinly stretched Luftwaffe, overburdened by a war on three fronts, essentially disappeared for several weeks. This also helped lull the Allies’ air and ground units into a dangerous overconfidence as Nazi Germany coiled to strike one last time.

Falling Undefeated

Ghastly devastation was wrought on the Third Reich during 1944. Also, every military historian knew the German Army traditionally did not launch major offensives during winter, especially when it was already and obviously beaten. Therefore, not since Pearl Harbor was the U.S. military so totally taken by surprise as at 5 am on December 16, 1944, when 600,000 undetected German soldiers exploded from the frozen Ardennes Forest in what would be known as the Battle of the Bulge. The worst weather in months cloaked Western Europe and protected the surging Wehrmacht from Allied air power.

Like the rest of the USAAF, the 352nd was socked in by the overcast and blizzards. Billeted in a forest clearing outside Asche, Belgium, the 328th Squadron gamely lifted off on December 23 in hopes of strafing enemy ground units, but after a fruitless patrol during which the cloud ceiling was so close to the ground the pilots had to dodge trees, they returned to base without firing a shot. Without reconnaissance flights, they did not know where to look for targets, and radio reports from ground units in the confused forest fighting contradicted each other. For the next two days the frustrated airmen wrote and read letters, played cards, and shot dice in their freezing forest encampment.

On Christmas Day, Preddy was one of 10 pilots who took off in hopes of supporting their infantry and armored units that were trying to stem the enemy stream grinding westward. They found nothing for three hours, then got a radio report of a flight of hostiles just to the southwest of Koblenz. Heading to the sector they found the bandits and attacked from above. Typically in the lead, Preddy flamed two Me-109s and led his men in pursuit of the rest of the Germans as they turned toward Liege.

Closing in on an FW-190, he opened fire at close range at the same time an American antiaircraft crew opened up on him. The ground gunners quickly realized they were shooting at one of their own planes and ceased fire, but it was too late. One of the .50-caliber bullets had gone through Preddy’s right thigh, severing his femoral artery. He crash landed near the flak pit, and infantrymen carried him to a field hospital, but he bled to death before reaching it.

Major George Preddy was never defeated in combat. At age 25 he had fallen prey to human error. With 27.5 confirmed kills, he was the war’s top-scoring Mustang ace despite having flown this magnificent aircraft for less than one year. All of this crystallizes his standing as one of America’s greatest war heroes.

On April 17, 1945, Preddy’s 20-year-old brother, William, a Mustang pilot with two victories, was killed by antiaircraft fire over Pilsen, Czechoslovakia.

Author Kelly Bell writes regularly on various aspects of World War II, including the air war in Western Europe. He resides in Tyler, Texas.

I like the article’s, thank you

The best writing on the internet…..I read two before going to bed. I never want to forget these guys sacrifices so we can live a great life.

A great read

Wow. What a story!

A pilot from Americas greatest generattion.

What an inspiring story about a great American. May God rest his soul and all the others who died in the European Theater.

I live in Greensboro NC, Preddy‘s hometown. There’s a street named after him, a foundation, an exhibit at the local museum, and other memorials to this brave young man.

It reads like a dramatic Hollywood movie, but without a happy Hollywood ending. How heartbreakingly sad.