By Paul B. Cora

Through the first half of World War II, Allied shipping losses to German U-boats climbed steadily from over 400,000 tons in the last four months of 1939 to more than two million tons each in 1940 and 1941, before reaching a staggering 6,266,215 tons in 1942 following the entry of the United States into the war. The success of the Kreigsmarine’s submarine fleet against Britain in particular made the defeat of the U-boats a prime objective of Allied planners. Throughout the war vast resources were committed to achieve it.

The rising toll of the U-boats and the shortage of purpose-built convoy escort vessels in the British Royal Navy during the war’s first year gave birth to the concept of the destroyer escort or “DE”—a U.S.-built warship type that was destined to become a mainstay of Allied convoy defense by the second half of World War II.

Smaller, slower, and less heavily armed than destroyers, DEs nevertheless had ample antisubmarine capabilities. The 1941 British Admiralty specification used in the design by the firm of Gibbs and Cox specified stowage for 112 depth charges, a state-of-the-art, forward-firing hedgehog antisubmarine projector, and dual-purpose main armament effective against both surface and air targets. Above all, the DEs were designed to be mass produced quickly and cheaply.

The First Destroyer Escorts

The first of some 563 DEs constructed during World War II were laid down using Lend-Lease funds at the U.S. naval shipyard, Mare Island, California. The first four went to Britain’s Royal Navy, while the fifth was commissioned into the U.S. Navy as USS Evarts (DE-5). Ultimately, 97 Evarts-class DEs were built with a third of them serving in the Royal Navy where they were known as the “Captain”-class escort ships.

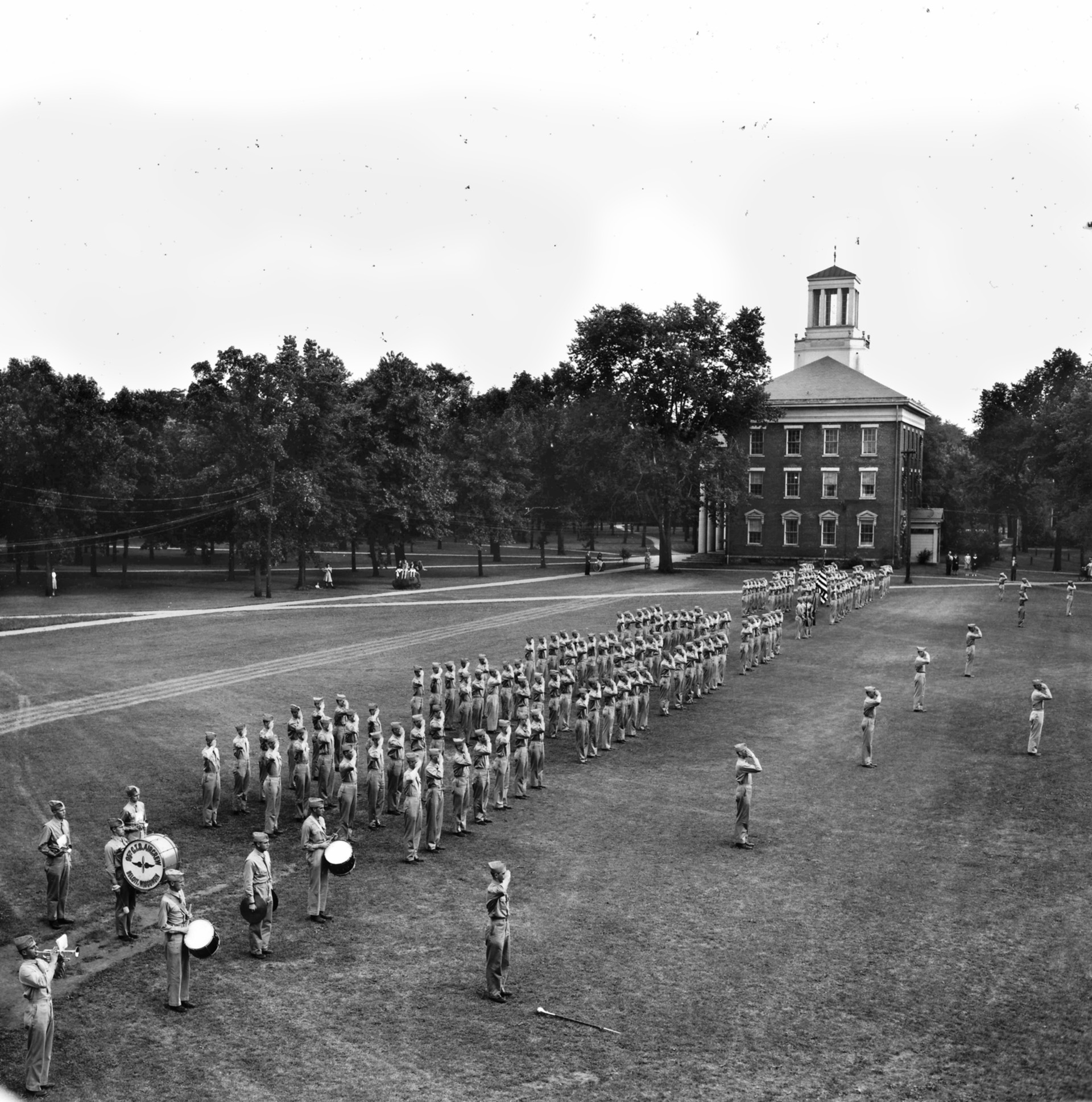

U.S. Navy destroyer escorts were named for deceased naval heroes, and many American sailors who gave their lives in the first years of the war would be so honored. Depending on their class and mission, DEs were manned by 180 to 220 officers and men.

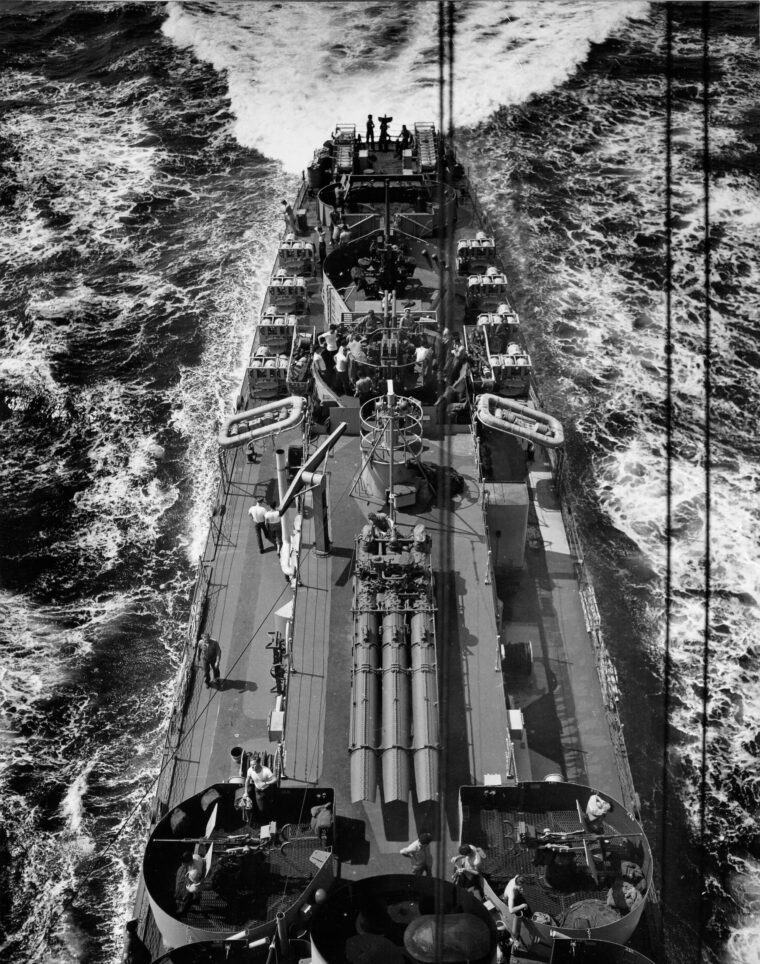

Evarts-class DEs were 289 feet, 5 inches long, with a beam of 35 feet, and an overall displacement of 1,360 tons fully loaded. Their original armament consisted of three 3-inch 50-caliber (3″/50) dual-purpose guns, a quad 1.1-inch antiaircraft mount, and nine 20mm single mount antiaircraft guns. For antisubmarine work, two depth charge racks were located aft, eight K-gun depth charge throwers were located amidships port and starboard, and a hedgehog projector was mounted forward of the bridge between the No. 1 and No. 2 3″/50s. For main propulsion, Evarts-class DEs were equipped with four General Motors diesel-electric generators that supplied power for the propulsion motors—a system known as GMT or General Motors Tandem drive. So powered, the twin-screw Evarts-class ships were capable of 20 knots.

By 1943, improvements in basic design and armament were on the way. For Buckley-class DEs, which soon followed in production, overall length was increased to 306 feet, and armament was beefed up to include a three-tube battery of 21-inch torpedoes placed amidships. Steam-driven, Buckley-class DEs were equipped with Foster-Wheeler boilers and General Electric geared turbo-generators, whose 12,000 shaft horsepower gave them a top speed of more than 23 knots. A second rudder improved steering and tightened their turning radius by 25 percent—a highly useful characteristic for hunting submarines. Fully loaded displacement on Buckley-class DEs increased to 1,720 tons from the smaller short-hulled Evarts class.

The four subsequent classes of DEs after the Buckley class retained the 306-foot overall length, though variations in main propulsion were dictated by shipyard capability and engine supplies. The 1,520-ton Cannon-class DEs were powered by General Motors diesel-electric drives identical to the main propulsion in the Evarts class, while those of the 1,490-ton Edsall class received Fairbanks-Morse diesel engines of the same type that powered the electric generators on many U.S. fleet-type submarines, directly coupled to the screws. Rudderow class ships displaced 1,811 tons fully loaded and, like the Buckleys, were steam-driven turbo-electric ships. Those of the 2,100-ton John C. Butler class received Westinghouse geared steam turbines and were capable of almost 30 knots. Unlike earlier designs, the Butlers and Rudderows received 5-inch 38-caliber (5″/38) enclosed gun mounts as main armament and destroyer-style enclosed bridges, as opposed to the tall open bridge of the original British design.

From the outset, DEs were fitted with electronic gear that made them effective at finding submarines, including sonar for hunting submerged U-boats and radar for picking them up on the surface. Some DEs also received high-frequency radio direction finding equipment (known as HFDF or “huffduff”), which allowed them to home in on radio signals sent by U-boats at sea.

Some 16 U.S. shipyards produced destroyer escorts during World War II. By 1944, DEs were operating in such quantity that they formed the backbone of antisubmarine defense in the Atlantic, where they not only protected convoys of merchant ships and troop transports, but also operated with escort aircraft carriers in highly effective hunter-killer groups that sought out and destroyed U-boats before they could strike.

Combat Experience

Among the most successful of these was the Edsall-class USS Pillsbury (DE-133), which, as part of a hunter-killer group led by the escort carrier USS Guadalcanal (CVE 60), depth-charged U-515 to the surface on April 8, 1944, then in company with her sister ship, USS Flaherty (DE-135), destroyed the sub in a gun battle. Some two months later, on June 4, 1944, the Pillsbury forced U-505 to the surface off the Cape Verde Islands. Her crew then boarded and captured the sub, furnishing the Allies with an invaluable intelligence coup. Awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for bagging U-505, Pillsbury’s exploits were far from over. On April 24, 1945, while operating in the North Atlantic, she depth charged and sank U-546.

Four U.S. destroyer escorts were lost to U-boats, including the USS Leopold (DE-319), one of 30 DEs manned by the U.S. Coast Guard during World War II. The Buckley-class USS Donnell (DE-56) was torpedoed by a U-boat off the British Isles while defending a convoy on May 3, 1944. Twenty-nine of Donnell’s crewmen were killed, but damage control measures saved her from sinking, although the damage proved too extensive for her to return to escort duty. In August 1944, however, the Donnell was towed across the English Channel and tied up at war-torn Cherbourg, where her still serviceable power plant was used to make electricity. The USS Holder (DE-401), was eventually scrapped after being seriously damaged in an April 1944 air attack off Algeria, and the USS Rich (DE-695) sank after hitting a mine off Normandy on June 8, 1944. Britain’s Royal Navy lost eight of the 78 DEs it acquired from the United States.

In the Pacific, DEs served with distinction as antisubmarine vessels and also carried out other tasks, including shore bombardment, radar picket, and troop carrying after being converted to fast-attack transports (APD).

Among the most famous DEs of the Pacific War was the Buckley-class USS England (DE-635), which, in just 12 days during May 1944, hunted down and sank five Japanese submarines and assisted in the destruction of a sixth. For this unequaled feat, the ship received a Presidential Unit Citation, prompting the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest J. King, to remark, “There’ll always be an England in the United States Navy.” The following spring, however, England’s combat exploits came to an end when a Japanese kamikaze slammed into her side, killing 37 of her crew and forcing her to steam to the U.S. for repairs.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf

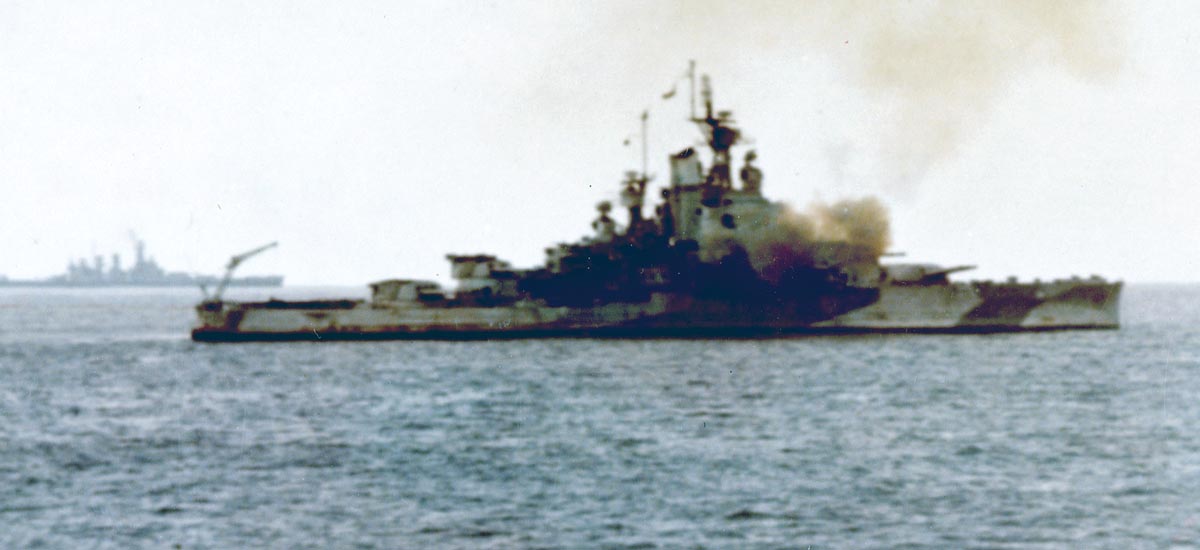

Some DEs in the Pacific were involved in actions for which they had never been designed, such as engaging major enemy surface ships. Off Samar on October 25, 1944, during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, four DEs were involved in the defense of a group of escort carriers that were caught by surprise and attacked by a powerful Japanese surface fleet under Admiral Takeo Kurita. When Kurita’s force of four battleships and some 19 cruisers and destroyers engaged six lightly protected escort carriers, the DEs John C. Butler (DE-339), Raymond (DE-341), Dennis (DE-405), and Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413) joined the three fleet destroyers assigned to their task unit, code-named Taffy 3, and charged the Japanese armada in a desperate defense.

After firing their 21-inch torpedo batteries at the oncoming Japanese, the destroyers and DEs opened fire with their 5-inch guns and continued to lay smoke screens in the hope that the escort carriers might slip away. During the action, the Samuel B. Roberts was able to score hits with her torpedoes as well as her 5-inch guns on the Japanese heavy cruiser Chokai, though the gallant DE was hit a short time later by numerous 8-inch and 14-inch shells and sank with the loss of nearly 100 men. In addition to the Samuel B. Roberts, two U.S. destroyers and one other escort carrier were lost at Samar, but the suicidal defense by the “tin cans” and DEs did much to save the day as Kurita withdrew believing he faced a much larger force.

Despite the effective use of 21-inch torpedoes at Samar by the DEs of Taffy 3, it was evident that destroyer escorts needed more antiaircraft protection. By mid-1944, many DEs originally equipped with torpedoes received four single-mount 40mm antiaircraft guns amidships in place of their torpedo batteries. The fitting of single-mount “Army-type” 40mm guns was primarily a stopgap measure intended to deal with increased German air activity in the Mediterranean. By 1945, antiaircraft protection on DEs operating in the Pacific would be further increased in the face of Japanese kamikaze attacks.

Beginning in 1944, some 95 DEs of the Buckley and Rudderow classes underwent conversion to fast attack transport (APD), some during their construction. After removal of torpedo tubes and aft deck guns, these ships were outfitted with stowage space and davits for four LCVP landing craft, cargo cranes, and a beefed- up superstructure that provided living space for troops. So transformed, APDs were capable of putting ashore a battalion of soldiers or Marines in an amphibious assault. In place of their forward 3-inch/50-caliber deck guns, Buckley-class APD conversions received a single 5-inch/38-caliber gun, and all APDs kept their depth charges while receiving an additional 40mm antiaircraft mount.

In the Pacific, six DEs were lost to enemy action. In addition to the Samuel B. Roberts, the USS Eversole (DE-404) and the USS Shelton (DE-407) were torpedoed by Japanese submarines, while the USS Underhill (DE-682) fell victim to a kaiten suicide craft off the Philippines. The USS Bates (APD 47) sank with the loss of 21 of her crew after being struck by a kamikaze off Okinawa on May 25, 1944. The USS Oberrender (DE-344) was so badly damaged by Japanese suicide planes off Okinawa that she was scrapped.

Legacy of the Destroyer Escort

After World War II, some DEs continued to serve in the U.S. Navy, frequently as training ships for the Naval Reserve. During the 1950s, some 36 DEs underwent conversion to radar pickets (DER) and were used, aside from fleet duties, as part of the Cold War’s DEW (Distant Early Warning) Line intended to protect the United States from surprise nuclear attack. Still other DEs went to foreign navies, in which some steamed on into the 1990s.

Though 563 DEs were built at U.S. shipyards during World War II—in itself an amazing industrial achievement—they have virtually disappeared today. A happy exception is the Cannon-class USS Slater (DE-766) operated as a floating museum and memorial on the Hudson River in Albany, New York. Lovingly restored by a dedicated group of professionals and volunteers, the Slater is the best example of a World War II DE to be found anywhere today. Step aboard DE-766 at Albany and step back in time to 1945—from the silverware and china laid out in the officer’s wardroom, to the virtually complete armament suite that includes depth charges and hedgehog projectors, 3-inch/50-caliber deck guns, and 20mm and 40mm antiaircraft mounts that seem ready to swing into action. Exploring this 309-foot warship, the visitor sees the Slater through the eyes of a World War II crewman. From the fully outfitted bridge and pilot house to the damage control lockers and living spaces, she appears ready to join a convoy under way.

The approach to the problem of the U-boat menace in World War II, largely embodied in the mass production of destroyer escorts, was a tribute to the capabilities of American industry and to Allied resolve. The place of DEs in the naval history of World War II, however, goes far beyond the Battle of the Atlantic, for these were extremely versatile ships. DEs and their crews took on a myriad of tasks in every theater of the war and succeeded far beyond what the designers of the little ships had ever imagined.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments